Achille Laugé stands as a distinctive figure within the vibrant landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born on August 29, 1861, and passing away on June 2, 1944, his life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. Primarily recognized as a Neo-Impressionist painter, Laugé developed a unique visual language characterized by his meticulous application of color theory and his profound connection to the sun-drenched landscapes of his native region in Southern France. Though perhaps less universally known than some of his contemporaries, his dedication to the principles of Divisionism, combined with a deeply personal sensitivity to light and form, secured him a significant place in the annals of art history. His journey from a rural upbringing to the art schools of Toulouse and Paris, and his eventual return to the quietude of the Aude department, shaped an oeuvre celebrated for its luminosity, structure, and serene beauty.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Achille Laugé was born in Arzens, a small commune in the Aude department of Southern France. His family background was rooted in the land; they were relatively prosperous farmers. This early immersion in the rural environment would profoundly influence his later artistic focus. Seeking a different path from agriculture, the young Laugé initially trained as a pharmacist in Toulouse. However, his true calling lay elsewhere.

His artistic inclinations soon led him to enroll at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse in 1876, where he studied until 1881. This period was crucial for his foundational training and for forging important early connections. It was in Toulouse that he met Antoine Bourdelle, who would become a renowned sculptor and a lifelong friend. This friendship highlights the interconnectedness of the artistic community, even in regional centers outside of Paris. The rigorous academic training in Toulouse provided Laugé with essential skills in drawing and composition, forming the bedrock upon which he would later build his more experimental style.

Parisian Studies and Influences

In 1882, driven by ambition and the desire to immerse himself in the epicenter of the art world, Laugé moved to Paris. He gained admission to the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the paramount institution for academic art training in France. There, he studied under prominent figures of the establishment, including the painter Alexandre Cabanel and the history painter Jean-Paul Laurens. Cabanel, known for works like "The Birth of Venus," represented the epitome of the academic tradition that Laugé and his generation would eventually react against.

Despite the academic environment, Paris exposed Laugé to revolutionary artistic currents. The air buzzed with the legacy of Impressionism and the emergence of new avant-garde movements. While at the École, Laugé reconnected with Antoine Bourdelle and also formed a close and enduring friendship with Aristide Maillol, another significant sculptor who, like Laugé, hailed from the south of France. They reportedly shared a studio for a time, fostering an environment of mutual support and artistic exchange.

Crucially, Laugé encountered the groundbreaking work of Georges Seurat, the pioneer of Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism or Divisionism. Seurat's systematic approach to color, applying small, distinct dots of pure pigment that would blend in the viewer's eye, offered a 'scientific' alternative to the more intuitive brushwork of Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. Laugé was deeply impressed by this method and the luminous effects it could achieve. He also saw exhibitions of Paul Cézanne's work, whose emphasis on underlying structure and geometric form likely resonated with Laugé's own developing sensibilities.

Embracing Neo-Impressionism

Inspired primarily by Georges Seurat and his circle, which included Paul Signac, Laugé began experimenting with the Divisionist technique around 1888. Neo-Impressionism was based on contemporary optical theories, suggesting that placing complementary colors side-by-side in small dots or strokes would create a more vibrant and luminous effect than mixing pigments on the palette. Laugé adopted this method, meticulously applying small dabs of color to build his compositions.

However, Laugé was not merely an imitator. While he embraced the core principles of Divisionism – the separation of colors and optical mixing – he adapted the technique to his own temperament and subject matter. Compared to the often systematic, almost rigid application seen in some of Seurat's major works, Laugé's touch could be more varied, sometimes employing slightly larger or more elongated strokes alongside dots. His palette, while based on scientific principles, often leaned towards softer harmonies, capturing the specific quality of light in Southern France.

He participated in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, a crucial venue for avant-garde artists operating outside the official Salon system. Exhibiting alongside fellow Neo-Impressionists like Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, and the Belgian Théo van Rysselberghe, Laugé positioned himself firmly within this modern movement. Despite this, his commitment to a style considered radical by the establishment meant he faced challenges; reports suggest his work was sometimes rejected by the more conservative official Paris Salon.

Return to the South: Cailhau as Sanctuary

After completing his studies and gaining exposure to the Parisian art scene, Laugé made a pivotal decision around 1895. He chose to leave the bustling capital and return to the Aude region, settling in Cailhau, the village where his family had moved during his youth. This return marked a deliberate withdrawal from the competitive center of the art world and a conscious choice to immerse himself in the landscape that resonated most deeply with him.

In Cailhau, Laugé adopted a relatively simple, almost reclusive lifestyle, dedicating himself almost entirely to his art. He even reportedly built himself a small hut or studio, further emphasizing his connection to the local environment and his independence. The landscapes surrounding Cailhau became his primary muse. He painted the rolling hills, the winding country roads, the vineyards, the almond trees in blossom, and the fields under the strong Mediterranean sun.

His deep familiarity with this region allowed him to capture its essence with remarkable sensitivity. He was particularly attuned to the effects of light and atmosphere at different times of day and during different seasons. His paintings often possess a distinct sense of place, characterized by clear light, sharp shadows, and an underlying geometric structure that recalls Cézanne's influence, yet rendered through the Neo-Impressionist technique.

Artistic Style and Signature Works

Laugé's mature style is defined by his commitment to Divisionism, tailored to his personal vision. His application of paint, often in small dots or slightly elongated strokes, creates a vibrant surface texture. He masterfully used color theory to depict the intense luminosity of the South, often juxtaposing warm and cool tones to represent sunlight and shadow. His compositions frequently feature strong diagonal lines, particularly in his depictions of roads receding into the distance, which lend a sense of depth and structure.

One of his most representative works is La route au lieu-dit "L'Hort" (The Road at the Place Called "L'Hort"). This painting exemplifies his approach: a sun-drenched country road, likely near Cailhau or perhaps inspired by scenes like those near the Forest of Compiègne mentioned in some sources, is rendered with meticulous dots of color. The interplay of light filtering through the trees and casting shadows on the road showcases his skill in capturing atmospheric effects through purely optical means. The composition is balanced, serene, yet vibrant with color.

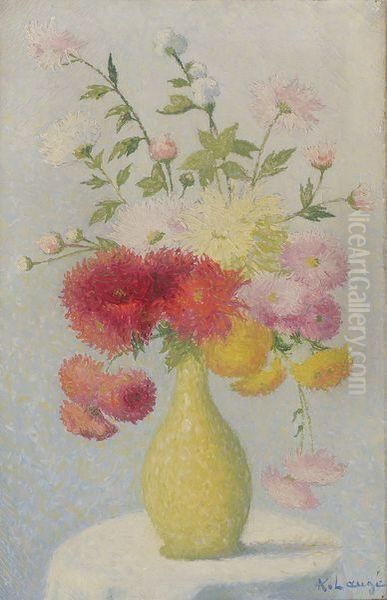

While landscapes dominated his output, Laugé also produced compelling still lifes and portraits. His Bouquet paintings demonstrate his ability to apply the Divisionist technique to arrangements of flowers, capturing their delicate forms and colors with the same careful analysis of light. These works often feature simple backgrounds, focusing attention on the intricate play of color within the floral arrangement itself. He also painted portraits, including tender depictions of his wife, Marie-Agnès Boyer, rendered with the same Neo-Impressionist technique, demonstrating the versatility of his chosen method.

Evolution and Later Career

While Laugé remained fundamentally committed to the principles of light and color separation learned from Neo-Impressionism throughout much of his career, some observers note subtle shifts in his technique over time. In his later years, while still focused on capturing light, his brushwork occasionally became somewhat freer, perhaps moving slightly away from the strict pointillist dot towards more expressive, though still distinct, strokes. Some later works might also incorporate a degree of impasto, adding physical texture to the paint surface.

Despite his relative isolation in Cailhau, Laugé continued to exhibit his work, maintaining connections with the art world, albeit from a distance. He remained dedicated to his chosen path, consistently exploring the nuances of the landscape around him. His focus rarely wavered from the core themes of light, color, and the structure of nature as observed in his immediate surroundings. His life was one of quiet dedication to his craft, finding fulfillment in the act of painting and the contemplation of the natural world.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Laugé's artistic journey was shaped not only by influences but also by his relationships with fellow artists. His friendships with sculptors Antoine Bourdelle and Aristide Maillol, formed during his student years, were particularly significant and endured throughout their lives. These connections provided mutual support and intellectual camaraderie, especially important for artists working outside the mainstream or returning to regional roots. Sharing a studio with Bourdelle in Paris fostered an environment of creative exchange during a formative period.

His relationship with the core Neo-Impressionist group, including Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, was primarily one of influence and shared ideals, particularly regarding the 'scientific' application of color. He exhibited alongside them at the Salon des Indépendants, aligning himself with their avant-garde stance. However, his geographical distance after returning to Cailhau likely meant less direct day-to-day interaction compared to those who remained central figures in the Parisian scene, like Signac.

While influenced by Impressionists like Monet and Pissarro in their approach to light and color, and by Cézanne in terms of structure, Laugé carved his own niche. He wasn't directly associated with the Fauvist explosion led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, nor the Cubist revolution of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, though these movements occurred during his mature career. His path remained anchored in the principles of Neo-Impressionism, interpreted through his unique sensibility and regional focus. His contemporaries also included figures like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, who were similarly exploring expressive color and form, though Laugé's approach remained more systematic and tied to observation.

Personal Life: Family and Simplicity

Contrary to some accounts suggesting a solitary life, Achille Laugé did marry. In 1891, he wed Marie-Agnès Boyer. Their marriage appears to have been a stable and supportive one, and the couple had four children: Pierre, Juliette, Jeanne, and Julien. The existence of portraits of his wife suggests she was an integral part of his life, both personally and occasionally as a subject for his art.

This family life unfolded primarily in the quiet setting of Cailhau. Laugé's decision to live there, away from the pressures and distractions of Paris, points to a desire for a life centered around his work and family, grounded in the rhythms of the countryside he loved to paint. His lifestyle was described as simple, suggesting a man content with his surroundings and dedicated to his artistic pursuits without needing the constant affirmation of the metropolitan art scene. This deliberate choice shaped both his life and his art, allowing for a deep, sustained engagement with his chosen subject matter.

Lack of Direct Disciples

While Achille Laugé was influenced by prominent teachers like Cabanel and Laurens, and deeply impacted by the work of Seurat, there is no significant historical record indicating that he himself took on students or apprentices in a formal capacity. His relatively secluded life in Cailhau after his Parisian period might have limited opportunities or inclination for teaching. His influence, therefore, seems to have been exerted primarily through his work itself, rather than through direct mentorship of a younger generation of artists. His legacy lies in the paintings he created and his unique contribution to the Neo-Impressionist movement.

Legacy and Art Historical Standing

During his lifetime, Achille Laugé achieved a degree of recognition, exhibiting his work and being associated with the Neo-Impressionist movement. However, he did not attain the same level of fame as some of his contemporaries like Monet, Renoir, or even the central figures of Neo-Impressionism like Seurat and Signac. His decision to retreat from Paris to Cailhau likely contributed to his relatively lower profile within the broader narrative of modern art as it was being written in the early 20th century.

It was largely after his death in 1944 that his work began to receive more focused critical attention and appreciation. Retrospective exhibitions helped to re-evaluate his contribution. Art historians came to recognize the quality, consistency, and unique beauty of his oeuvre. His sensitive application of Divisionist principles to capture the specific light and atmosphere of Southern France was increasingly acknowledged as a significant achievement.

Today, Achille Laugé is regarded as an important, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in French Post-Impressionism, specifically within the Neo-Impressionist current. His paintings are admired for their luminous quality, their structural clarity, and their serene depiction of the French countryside. His works are held in prestigious museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and numerous regional museums in France. His dedication to his personal artistic vision and his profound connection to his native landscape continue to resonate with viewers.

Conclusion: The Quiet Luminist

Achille Laugé's artistic legacy is one of quiet dedication and luminous beauty. As a key proponent of Neo-Impressionism in France, he masterfully adapted the Divisionist technique to capture the unique light and structure of the Aude region. While his friendships with figures like Bourdelle and Maillol connected him to the broader art world, his heart and his art remained firmly rooted in the landscapes of Southern France following his return from Paris.

His paintings, whether depicting sun-drenched roads, blossoming orchards, or carefully arranged bouquets, are testaments to a patient, observant eye and a sophisticated understanding of color theory. Though perhaps overshadowed during his lifetime by artists who remained in the Parisian limelight, Laugé's consistent vision and the serene, light-filled quality of his work have earned him a lasting place in art history. He stands as a reminder that significant artistic contributions often flourish away from the bustling centers, nurtured by a deep connection to place and a steadfast commitment to a personal aesthetic vision. His art continues to offer a window onto the tranquil beauty of the French countryside, rendered through the vibrant prism of Neo-Impressionist color.