Émile Van Marcke de Lummen stands as a significant figure in 19th-century French art, celebrated primarily for his evocative landscapes and masterful depictions of animals, particularly cattle. Born into an artistic lineage deeply connected with the renowned Sèvres porcelain manufactory, Van Marcke carved his own path, transitioning from ceramic decoration to oil painting, becoming a prominent exponent of the pastoral tradition influenced by the Barbizon School. His works, characterized by their naturalism, sensitivity to light, and affectionate portrayal of rural life, found favour not only in France but also across the Atlantic, securing his place in the annals of European art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

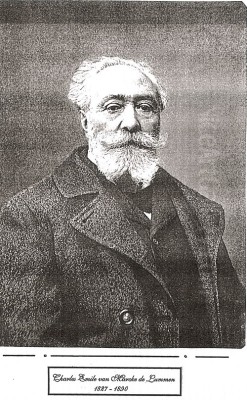

Émile Van Marcke de Lummen was born on August 20, 1827, in Sèvres, Hauts-de-Seine, France. This location was pivotal, as Sèvres was, and remains, synonymous with the highest quality porcelain production. His family background was steeped in this artistic environment. His father, Jean-Baptiste Jules Van Marcke (often cited simply as Jean-Baptiste Van Marcke), was himself a respected painter and designer associated with the Sèvres factory, known for his skill in depicting animals on porcelain. The artistic roots extended further back, with his grandfather, Charles van Marcke, being a noted porcelain painter originally from Belgium who had settled in France.

His mother, Victorine Robert, added another layer to this artistic milieu, being the daughter of Louis Robert, who was the director of the painting and gilding studios at the Sèvres manufactory. Growing up surrounded by artists and artisans undoubtedly shaped young Émile's sensibilities and provided him with early exposure to artistic techniques and aesthetics. It was natural, therefore, that he would pursue formal art training locally.

Following his initial studies, Émile Van Marcke embarked on a career path that mirrored his father's beginnings. From 1853 until 1862, he worked as a painter and decorator at the Sèvres porcelain factory. This period was crucial for honing his technical skills, particularly his precision in drawing and his understanding of decorative composition. Working on porcelain demanded meticulous attention to detail, a quality that would later translate into the careful rendering seen in his oil paintings.

The Influence of Constant Troyon and the Barbizon School

A turning point in Van Marcke's artistic development came through his association with Constant Troyon (1810-1865). Troyon, initially also a porcelain decorator at Sèvres, had emerged as one of the leading animal painters (animaliers) of his generation and a key figure associated with the Barbizon School. The Barbizon School, active roughly from the 1830s to the 1870s, championed a move away from Neoclassical formality and Romantic melodrama towards a more direct, naturalistic depiction of landscapes and rural life. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny sought inspiration directly from nature, often painting outdoors (en plein air) in the Forest of Fontainebleau near the village of Barbizon.

Troyon became a mentor figure for Van Marcke. Under Troyon's guidance and inspired by his success, Van Marcke began to shift his focus from porcelain decoration towards oil painting on canvas. He embraced the Barbizon ethos, turning his attention to the landscapes and, most significantly, the animal life of the French countryside. Troyon's influence is evident in Van Marcke's choice of subject matter – particularly his fondness for cattle – and his commitment to capturing the textures and forms of animals with accuracy and empathy.

While deeply influenced by Troyon, Van Marcke developed his own distinct style. Some critics noted that Van Marcke's work, perhaps reflecting his background in decorative arts, occasionally possessed a slightly more polished or refined finish compared to the sometimes rougher, more vigorous brushwork of Troyon or other Barbizon painters like Millet. However, his core commitment remained aligned with the Barbizon pursuit of naturalism and the celebration of the pastoral ideal. He frequently depicted the lush pastures and marshlands of Normandy, capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the region.

Artistic Style and Subject Matter

Émile Van Marcke de Lummen's oeuvre is primarily defined by his dedication to animal painting within landscape settings. Cattle were his most frequent subjects, often shown grazing peacefully in fields, gathered around watering holes, or being herded along country paths. He depicted these animals not merely as generic elements within a landscape but as individuals possessing distinct characteristics and presence. His anatomical accuracy was highly regarded, reflecting careful observation and skilled draughtsmanship honed during his years at Sèvres.

His landscapes served as more than mere backdrops; they were integral components of the composition, imbued with atmosphere and a sense of place. He excelled at rendering the textures of the natural world – the lushness of grass, the reflective surface of water, the changing quality of light under different weather conditions. Normandy, with its verdant fields and distinctive rural architecture, provided a recurring source of inspiration. Works often feature the interplay of sunlight and shadow, creating depth and highlighting the forms of the animals and the contours of the land.

Van Marcke's palette was generally naturalistic, favouring earthy tones, rich greens, and blues, capturing the specific colours of the French countryside. His brushwork, while detailed, often retained a certain fluidity, avoiding photographic rigidity. He managed to convey both the tranquil beauty of rural life and the quiet dignity of the animals that inhabited it. His compositions are typically well-balanced, often employing diagonal lines or groupings of animals to lead the viewer's eye into the scene.

Compared to some other animaliers of the time, Van Marcke's work generally focused on the peaceful coexistence of animals and nature. While he could depict dramatic weather, like in "The Approach of a Storm," his prevailing mood was one of pastoral serenity. He shared this focus on domestic animals and rural labour with artists like Charles Jacque, known for his sheep and poultry, though Jacque's style often had a more rustic, Millet-like quality.

Signature Works and Recognition

Throughout his career, Émile Van Marcke de Lummen produced a substantial body of work, regularly exhibiting at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Success at the Salon was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial viability in the 19th century, and Van Marcke achieved considerable recognition through these exhibitions.

Several paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

_Vaches à la pâture_ (Cows in Pasture, c. 1875): A quintessential Van Marcke work, likely depicting a tranquil scene of cattle grazing, showcasing his skill in rendering animal forms and the textures of the landscape under natural light. Such scenes were his forte and highly sought after.

_Shepherd_ (1872): This work highlights his ability to integrate human figures naturally within the pastoral landscape, alongside the animals that were his primary focus. It evokes a sense of timeless rural activity.

_In the Marshes_ (1880): Demonstrating his interest in specific regional landscapes, this painting likely captures the unique atmosphere and vegetation of the Normandy marshlands, perhaps featuring cattle navigating the damp terrain.

_The Pasture Pool_ (c. 1880): Often depicting cattle drinking or resting near water, this theme allowed Van Marcke to explore reflections and the interplay of light on water surfaces, adding another layer of visual interest to his pastoral scenes. An oil painting with this title was sold at auction in 2014, attesting to the continued market interest in his work.

_The Approach of a Storm_ (1872): This work shows his capacity to handle more dramatic atmospheric effects, capturing the tension in the air and the changing light before a storm breaks, while still focusing on the reaction of the animals within the landscape.

_L’Arrosage au prairie_ (Watering in the Meadow, c. 1857): An earlier work possibly reflecting his transition period or early establishment of his characteristic themes, focusing on the essential activities of rural animal husbandry.

Van Marcke's success was not confined to France. His paintings became highly popular among collectors in Great Britain and, particularly, the United States during the Gilded Age. Prominent American collectors such as John Taylor Johnston, Cornelius Vanderbilt, William T. Walters of Baltimore, and even John D. Rockefeller acquired his works. This transatlantic appeal speaks to the universal attraction of his peaceful, idealized visions of rural life, which offered a comforting contrast to the rapid industrialization occurring in both Europe and America.

Contemporaries and the Animalier Tradition

Émile Van Marcke de Lummen worked during a period when animal painting, or the animalier tradition, enjoyed significant popularity in Europe. He was part of a vibrant community of artists specializing in this genre, building upon the legacy of earlier painters and contributing to its development.

His mentor, Constant Troyon, was arguably the most direct influence. Other key figures in the Barbizon School also depicted animals within their landscapes, though often secondary to the landscape itself, such as Jean-François Millet's portrayal of sheep and farm workers, or Charles-François Daubigny's riverside scenes that might include waterfowl or cattle. Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña and Jules Dupré, also Barbizon associates, primarily focused on forest interiors and dramatic landscapes, respectively, but the overall Barbizon emphasis on nature provided a fertile ground for animal painting.

Beyond the core Barbizon group, Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) was perhaps the most famous female animal painter of the era, known for her powerful, large-scale depictions of horses (like The Horse Fair) and other animals, rendered with remarkable realism. Charles Jacque (1813-1894), another artist associated with Barbizon, specialized in more intimate scenes of sheep, chickens, and farm interiors, often with a rustic charm.

Other contemporaries included Eugène Lambert (1825-1900), who gained renown specifically for his charming paintings of cats. Hippolyte Lalaisse (1810-1884) was known for his depictions of horses, often in military or working contexts. The Belgian painter Eugène Verboeckhoven (1798-1881) was a highly successful and technically polished painter of sheep and cattle, representing a slightly earlier generation whose detailed style may have also resonated within the broader European market. Philippe Rousseau (1816-1887), not to be confused with Théodore Rousseau, painted still lifes but also animals, sometimes humorously. Jacques Raymond Brascassat (1804-1867) was another important French animalier, known for his studies of bulls and landscapes.

Van Marcke's position within this field was characterized by his consistent focus on cattle within serene, often Normandy-based, landscapes, rendered with a blend of Barbizon naturalism and a refined technique that appealed to a broad audience. He successfully navigated the art market, creating works that were both artistically respected and commercially desirable.

Later Life and Legacy

Émile Van Marcke de Lummen continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, maintaining his studio in Paris but frequently travelling to the countryside, especially Normandy, for inspiration. He passed away in 1890 at the age of 62.

His artistic legacy endured through his paintings, which remain appreciated for their technical skill and tranquil beauty. They are held in numerous museum collections in France, the United States, and elsewhere, as well as in private collections. His work continues to appear at auction, demonstrating sustained interest among collectors of 19th-century European art.

Furthermore, Van Marcke contributed to the continuation of the animalier tradition through his family. His daughter, Marie Dieterle (née Van Marcke, 1856-1935), became a successful painter in her own right. Trained by her father, she specialized in similar subjects – landscapes with cattle and sheep – working in a style clearly influenced by his teachings and the Barbizon aesthetic. Her success highlights the familial transmission of artistic skills and thematic interests.

There is also mention of the German landscape painter Adolf Kaufmann (1848-1916) having studied with Van Marcke, suggesting his role extended to teaching beyond his immediate family, influencing artists from other countries who were drawn to the French landscape tradition.

In the broader context of art history, Émile Van Marcke de Lummen is remembered as a leading animal painter of the second half of the 19th century. He successfully synthesized the naturalistic impulses of the Barbizon School with a sensitivity to composition and finish that perhaps stemmed from his early training in decorative arts. He captured an idealized yet believable vision of French rural life that resonated deeply with the tastes of his time and continues to hold appeal for its peaceful charm and artistic merit.

Conclusion

Émile Van Marcke de Lummen occupies a respected place in 19th-century French art. Bridging the gap between the decorative arts of Sèvres porcelain and the naturalistic landscapes of the Barbizon School, he became a master interpreter of pastoral life. His paintings, particularly those featuring cattle in the lush settings of Normandy, are celebrated for their technical proficiency, atmospheric sensitivity, and gentle portrayal of the natural world. Influenced by his artistic family and mentored by Constant Troyon, he developed a distinctive style that earned him international acclaim and popularity, especially among American collectors. Alongside contemporaries like Rosa Bonheur and Charles Jacque, he significantly contributed to the animalier genre, leaving behind a legacy of tranquil, beautifully rendered scenes that continue to evoke the enduring allure of the French countryside. His work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of pastoral themes and the skillful depiction of animals in harmony with their environment.