Emily Carr stands as one of Canada's most revered and iconic artists, a figure whose life and work are deeply intertwined with the formidable landscapes and rich Indigenous cultures of British Columbia. A painter and writer of profound originality and fierce independence, Carr forged a unique artistic path, translating the spirit of the Pacific Northwest into a powerful visual language that continues to resonate. Her journey was one of relentless exploration, both of the external world of forests and First Nations villages, and the internal world of artistic expression and spiritual seeking.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Victoria, British Columbia, on December 13, 1871, Emily Carr was the second youngest of five children in a family of English immigrants. Her childhood, spent in the relatively conservative colonial society of Victoria, was marked by an early sense of being an outsider. Her parents, Richard and Emily (Saunders) Carr, maintained strict English customs, which the young, free-spirited Emily often chafed against. The early deaths of her mother in 1886 and her father in 1888 left her and her siblings under the guardianship of their eldest sister, Edith. This period of loss and constrained upbringing likely fueled Carr's independent nature and her later search for belonging and meaning outside conventional society.

From a young age, Carr displayed a passion for drawing and the natural world surrounding Victoria. Recognizing her talent, her family eventually supported her desire for formal art training. In 1890, at the age of 19, she traveled to San Francisco to study at the California School of Design. Here, she received a traditional academic grounding, focusing on drawing from casts and live models, and landscape painting. While providing foundational skills, the conservative approach of the school left her yearning for more expressive possibilities.

Seeking Modernism Abroad: London and Paris

Seeking broader horizons, Carr sailed for England in 1899. She enrolled at the Westminster School of Art in London, hoping to immerse herself in the European art scene. However, the rigid academicism prevalent in many British art institutions proved stifling. She found some inspiration in the work of artists who engaged with landscape, perhaps seeing echoes of the natural world she missed, but the overall experience was challenging. She later studied at various private studios and schools, including a period in St Ives, Cornwall, an artists' colony known for its landscape painters, and later at a school in Bushey, Hertfordshire, run by the popular painter Hubert von Herkomer, whose focus was more illustrative and academic.

A pivotal moment came during her time in England when she likely saw works by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, though her full immersion in modern art would come later. Health problems, possibly related to the emotional strain and dissatisfaction with her studies, led to a period of recuperation in a sanatorium before she returned to British Columbia in 1905, feeling somewhat disillusioned with her European training thus far.

Determined to find a more vibrant and contemporary approach, Carr returned to Europe in 1910, this time heading directly to France. This period proved transformative. In Paris, she studied at the Académie Colarossi and attended classes given by artists attuned to modern developments. She encountered Fauvism, with its explosive, non-naturalistic use of color championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain. She also deepened her understanding of Post-Impressionism, particularly the expressive intensity and subjective vision of Vincent van Gogh and the structural forms and symbolic color of Paul Gauguin. The French artists' emphasis on personal feeling, bold brushwork, and vibrant palettes resonated deeply with Carr, offering her the tools to express the powerful landscapes and cultures she knew back home.

Return to Canada: Documenting Indigenous Cultures

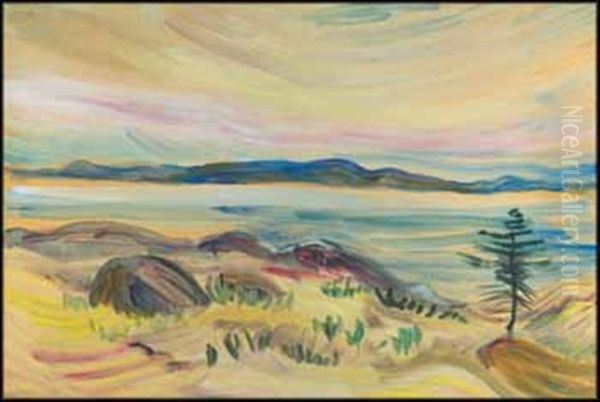

Returning to British Columbia in 1911, Carr was armed with a new, modern artistic vocabulary. She felt an urgent need to apply these techniques to the subjects that increasingly captivated her: the First Nations cultures of the Pacific Northwest and their monumental art, particularly the totem poles she had encountered on earlier trips. In 1912, she embarked on a significant sketching trip along the coast, visiting Indigenous villages on Haida Gwaii (then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands) and along the Skeena and Nass Rivers, home to the Gitxsan, Nisga'a, and Tsimshian peoples.

She felt a profound connection to the people she met and a deep respect for their artistic traditions, which she saw as rapidly disappearing under the pressures of colonization and government assimilation policies. Carr believed it was her mission to document this heritage before it vanished. Working often in challenging conditions, she created a remarkable series of watercolors and oil paintings depicting totem poles in their village settings, capturing not just their physical forms but also attempting to convey their spiritual presence and the encroaching power of the surrounding forests. Works from this period show her applying Fauvist-inspired color and Post-Impressionist brushwork to these uniquely North American subjects.

Despite the artistic breakthrough this represented for Carr, her new style met with incomprehension and ridicule back in Vancouver and Victoria. The public and critics, accustomed to more traditional, picturesque landscapes, found her bold colors and expressive forms jarring and crude. Discouraged by the lack of recognition and struggling financially, Carr largely abandoned painting for nearly fifteen years. To support herself, she ran a boarding house in Victoria (dubbed the "House of All Sorts"), raised sheepdogs, and made pottery decorated with Indigenous motifs, which she sold to tourists. Though a period of artistic silence, this time likely deepened her connection to the land and perhaps allowed her ideas to mature.

Encounter with the Group of Seven and Renewed Purpose

A crucial turning point occurred in 1927. Carr was invited to participate in the Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. The exhibition included her works alongside those of prominent First Nations artists and members of the Group of Seven, the leading force in modern Canadian art based primarily in Ontario. Traveling east for the exhibition, Carr met members of the Group, including Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley.

This encounter was profoundly validating and revitalizing for Carr. She found kindred spirits in the Group members, who shared her commitment to forging a distinctly Canadian art, breaking free from European conventions, and engaging directly with the Canadian landscape. They praised her work, recognizing its power and originality, which gave her the confidence to fully embrace her artistic vision.

The connection with Lawren Harris proved particularly significant. Harris, a leading figure in the Group known for his increasingly abstracted and spiritualized landscapes, became a close friend, mentor, and correspondent. He encouraged Carr to push her art further, to move beyond mere documentation towards expressing the underlying spirit and rhythm of her subjects. Harris's own interest in Theosophy and transcendental ideas about nature resonated with Carr's burgeoning spiritual connection to the forests and Indigenous art of the West Coast. His influence can be seen in the increased simplification, monumentality, and spiritual depth of her subsequent work. Although geographically distant and never a formal member, Carr became closely associated with the spirit and nationalistic aims of the Group of Seven.

Mature Style: Indigenous Themes Reimagined

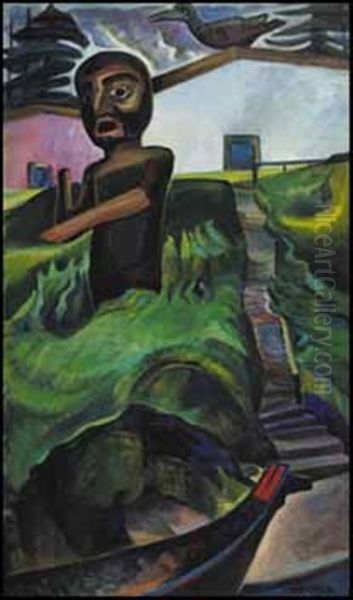

Energized by her interactions with the Group of Seven, Carr entered the most productive and powerful phase of her career. She returned to her Indigenous themes, but now approached them with greater stylistic freedom and emotional depth. Her focus shifted from ethnographic documentation to capturing the spiritual essence and monumental presence of the totem poles and the deep connection between culture and nature.

Her palette became richer, her forms more simplified and sculptural, and her brushwork more dynamic and rhythmic. Paintings like Indian Church (1929), arguably her most famous work, exemplify this mature style. The painting depicts a small white church dwarfed by the towering, vibrant green forms of the surrounding rainforest. It speaks to the complex encounter between European and Indigenous cultures, the power of nature, and a sense of spiritual searching. The simplified, almost abstract forms of the forest show the influence of Harris, yet the emotional intensity and specific sense of place are uniquely Carr's.

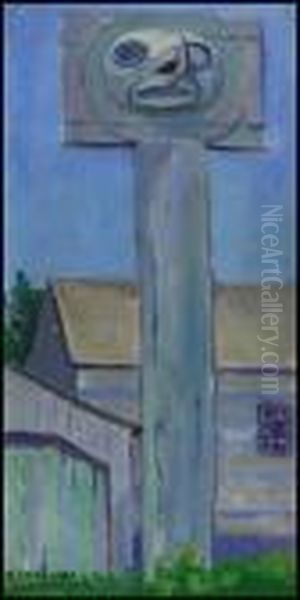

Other works from this period, such as Big Raven (1931) and Zunoqua of the Cat Village (based on earlier sketches), portray totem figures not just as artifacts but as living presences imbued with spiritual power, often set against swirling, dynamic representations of the forest or sky. She sought to convey the "spirit" of the poles and the forests they inhabited, using rhythmic lines and resonant color to express their life force.

Mature Style: The Spirit of the Forest

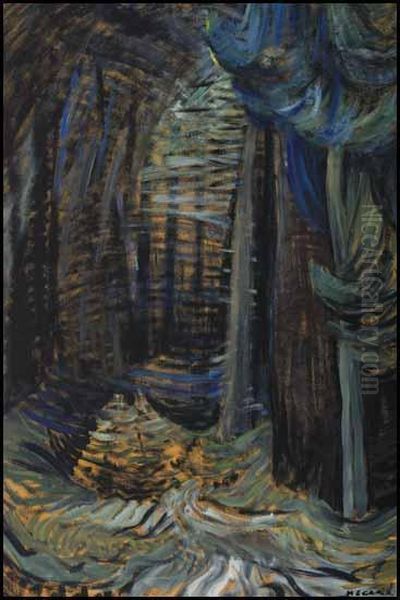

Around 1931-1932, Carr's primary focus began to shift from explicit Indigenous iconography towards the forest landscape itself. While her reverence for First Nations art remained, she increasingly found the spiritual connection she sought directly within the towering trees, tangled undergrowth, and shifting light of the British Columbia rainforests. This shift may have been partly influenced by the practical difficulties of traveling to remote villages as she aged, but it also represented a deepening of her personal, pantheistic spirituality.

Her forest paintings are among her most celebrated works. She abandoned the tighter structures of her earlier French-influenced period for a looser, more fluid style. Using oil paints thinned with gasoline, she achieved a new luminosity and dynamism. Her brushstrokes became swirling vortices of energy, capturing the movement of wind through the trees, the dappled sunlight filtering through the canopy, and the upward thrust of the giant cedars and firs.

Works like Forest, British Columbia (c. 1931-32), Tree Trunk (1931), and Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky (c. 1935) are powerful expressions of nature's overwhelming force and spiritual presence. She often painted from low vantage points, emphasizing the monumental scale of the trees reaching towards the sky, which became a recurring symbol of transcendence and spiritual aspiration in her work. The forest was not merely a landscape subject for Carr; it was a cathedral, a living entity pulsating with energy and spirit. Her later works sometimes verge on abstraction, as forms dissolve into rhythmic patterns of light and color, conveying an ecstatic, almost mystical experience of nature. This later phase also shows an affinity with the work of American Northwest artists like Mark Tobey, whom she met and whose calligraphic "white writing" may have influenced her fluid brushwork.

The Writer Emerges

Parallel to her renewed painting career, Carr began to find her voice as a writer. Encouraged by friends like Ira Dilworth, a CBC executive, she started writing stories based on her experiences, particularly her encounters with First Nations people during her earlier travels. Her first book, Klee Wyck (a name given to her by the Nuu-chah-nulth people, meaning "Laughing One"), was published in 1941.

Composed of vivid, empathetic, and often humorous sketches of Indigenous life and art, Klee Wyck was an immediate success. It won the prestigious Governor General's Award for Non-Fiction, bringing Carr national acclaim as a writer just as her painting was gaining wider recognition. The book's direct, unadorned prose and insightful observations revealed another facet of her talent for capturing the essence of the West Coast.

She followed Klee Wyck with several other books, including The Book of Small (1942), a charming memoir of her Victoria childhood; The House of All Sorts (1944), recounting her experiences as a landlady; and the posthumously published autobiography Growing Pains (1946), which provides invaluable insights into her life and artistic struggles. Her writing, like her painting, is characterized by its honesty, keen observation, deep feeling, and unique voice.

Personality and Eccentricities

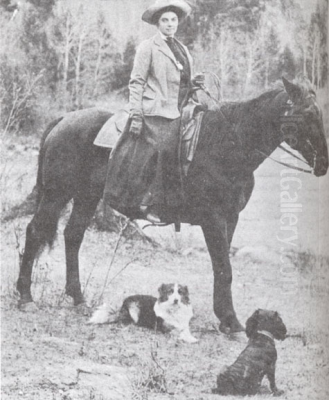

Emily Carr was known throughout her life as a strong-willed, unconventional, and often solitary figure. In the conservative society of Victoria, her dedication to her art, her rejection of conventional female roles, and her eccentric habits set her apart. She was famously devoted to her animals, keeping a menagerie that included numerous dogs, cats, birds, and even a pet monkey named Woo, who often accompanied her on sketching trips.

She developed a reputation for being gruff and outspoken, fiercely protective of her independence and her artistic integrity. Yet her writings reveal a deep capacity for empathy, humor, and self-reflection. Her later years were marked by recurring health problems, including heart attacks that limited her ability to travel to the remote landscapes she loved. Despite physical limitations and periods of loneliness, she continued to paint and write with remarkable energy and determination until the end of her life. She often worked in a caravan trailer she called "The Elephant," which allowed her to be close to the forests even when she couldn't trek deep into them.

Legacy and Influence

Emily Carr died in Victoria on March 2, 1945. She left behind a powerful legacy as one of Canada's foremost modern artists and writers. Her work fundamentally shaped the perception of the British Columbia landscape and brought unprecedented attention to the art and cultures of its First Nations peoples. She successfully synthesized European modernist influences – from Post-Impressionism and Fauvism – with uniquely North American subjects, creating a style that was entirely her own.

Her bold, expressive paintings of totem poles and forests captured the raw energy and spiritual depth of the West Coast in a way no artist had before. Along with the Group of Seven, she helped define a distinctly Canadian approach to modern art, one rooted in the direct experience of the land. Her influence can be seen in subsequent generations of West Coast artists, such as Jack Shadbolt and E.J. Hughes, who continued to explore the region's unique environment.

While contemporary perspectives sometimes raise complex questions about her position as a settler artist depicting Indigenous cultures, her work remains significant for its historical role in documenting First Nations art during a period of suppression and for the evident respect and empathy she conveyed. Her dual achievement as both a major painter and an accomplished writer makes her a unique figure in Canadian cultural history. Today, her paintings are celebrated in major galleries across Canada and internationally, and her books continue to be read and cherished, securing her place as a national icon and a visionary interpreter of the Canadian spirit.