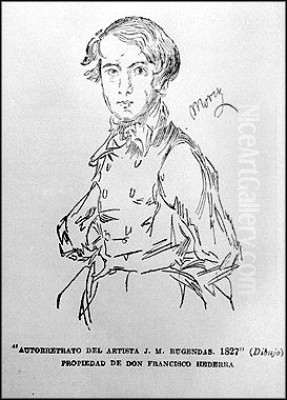

Johann Moritz Rugendas stands as a pivotal figure in the visual documentation of 19th-century Latin America. A German painter born into an era of burgeoning Romanticism and scientific exploration, Rugendas dedicated much of his life to traversing the vast and diverse landscapes of the newly independent nations of South and Central America. His prolific output, encompassing thousands of drawings, watercolors, and oil paintings, offers an unparalleled window into the continent's natural environments, its varied peoples, and its complex social fabrics during a period of profound transformation. Bridging the gap between artistic sensibility and ethnographic observation, Rugendas created a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of the Americas in the post-colonial era.

Augsburg Roots and Artistic Formation

Johann Moritz Rugendas was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, in 1802, into a family with a distinguished artistic lineage stretching back several generations. The Rugendas family was known for its painters and engravers, particularly those specializing in battle scenes and animal depictions. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured young Johann Moritz's artistic inclinations. His father, Johann Lorenz Rugendas II, served as the director of the city's art academy, providing early exposure to formal training and the artistic discourse of the time.

Following his initial studies in Augsburg, Rugendas moved to Munich around 1817 to further his education at the Academy of Fine Arts. There, he studied under figures such as Albrecht Adam, a noted painter of battle scenes and horses, which likely resonated with the Rugendas family tradition. However, reports suggest Rugendas grew somewhat restless with the constraints of purely academic training. He developed a strong preference for drawing directly from nature, focusing on landscapes and animal studies, particularly horses, foreshadowing the observational intensity that would characterize his later work abroad.

This early grounding in the German artistic tradition, combined with a burgeoning desire for direct engagement with the natural world, set the stage for the defining chapter of his life: his extensive travels through Latin America. He absorbed the technical skills of drawing and painting prevalent in early 19th-century Germany, but his spirit yearned for subjects beyond the familiar European scope.

The Brazilian Expedition: A New World Unfolds

The pivotal moment in Rugendas's career arrived in 1821 when he secured a position as a draftsman for the scientific expedition led by Baron Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, the Russian Consul General in Brazil. This expedition, typical of the era's European scientific curiosity about the wider world, aimed to explore and document the natural history, geography, and ethnography of Brazil's interior. For the young artist, barely nineteen years old, it was an extraordinary opportunity to escape the confines of Europe and immerse himself in a dramatically different environment.

Sailing to Brazil, Rugendas joined Langsdorff's team in Rio de Janeiro. His initial task was to produce accurate visual records of the flora, fauna, landscapes, and inhabitants encountered by the expedition as it moved through regions like Minas Gerais. He diligently filled sketchbooks with detailed drawings and watercolors, capturing the lush tropical vegetation, exotic animals, and diverse human types – indigenous peoples, Afro-Brazilians, and European colonists – that populated the vast territory.

However, the relationship between the artist and the expedition leader eventually soured. By 1824, Rugendas felt constrained by the scientific focus and perhaps the hierarchical structure of the Langsdorff mission. He parted ways with the expedition, choosing instead to embark on his own independent explorations of Brazil. This decision marked a crucial step towards artistic autonomy, allowing him to pursue subjects and perspectives dictated by his own interests rather than the specific requirements of scientific documentation.

Independent Exploration and the Voyage Pittoresque

Freed from the constraints of the Langsdorff expedition, Rugendas traveled extensively throughout Brazil between 1824 and 1825. He ventured into regions such as Bahia and Pernambuco in the northeast, and further explored the areas around Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. During this period, his focus broadened beyond purely scientific illustration. He became increasingly interested in capturing the essence of Brazilian life, including urban scenes, rural landscapes, plantation activities, and the diverse cultural practices he witnessed.

His sketches and studies from this period reveal a keen eye for detail and a growing ability to convey the atmosphere and unique character of the Brazilian environment. He documented not only the grandeur of the natural world but also the social realities, including the pervasive institution of slavery. Works depicting enslaved Africans, such as studies later titled Negros Novos (New Negroes) or Casa de negros (Slave Quarters), provide valuable, if sometimes filtered through a European lens, visual evidence of this brutal aspect of Brazilian society.

Upon returning to Europe in 1825, Rugendas settled briefly in Paris, a major center of the art world. There, he began the monumental task of transforming his vast collection of Brazilian sketches and watercolors into a publishable format. Collaborating with French lithographers and the writer Victor Aimé Huber, he produced his magnum opus: Malerische Reise in Brasilien (Picturesque Voyage to Brazil), published in installments between 1827 and 1835. This lavish publication, containing over one hundred finely executed lithographs with accompanying text, became one of the most significant visual accounts of Brazil produced in the 19th century. It cemented Rugendas's reputation as a skilled artist and an intrepid chronicler of the New World.

The Voyage Pittoresque, as it was known in its French edition, offered European audiences an unprecedented glimpse into the landscapes, peoples, and customs of Brazil. It stood alongside the work of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret, who was also active in Brazil during the same period and published his own Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil. While both artists documented Brazil, their approaches differed; Debret often focused more explicitly on court life and the social hierarchy, while Rugendas maintained a strong emphasis on landscape and ethnographic types, albeit with significant social observation woven in.

Humboldt's Influence: The Physiognomy of Nature

Rugendas's work resonated deeply with one of the most influential scientific minds of the era: Alexander von Humboldt. The renowned Prussian naturalist and explorer, whose own travels in the Americas (1799-1804) had revolutionized European understanding of the continent, became a significant admirer and supporter of Rugendas. Humboldt championed a holistic view of nature, emphasizing the interconnectedness of geology, climate, flora, fauna, and human culture. He believed that landscape painting could be a powerful tool for conveying this understanding, coining the term "Physiognomie der Natur" (Physiognomy of Nature) to describe the characteristic appearance of different regions of the Earth.

Humboldt saw in Rugendas an artist capable of capturing this "physiognomy." He praised the Voyage Pittoresque and encouraged Rugendas to continue his explorations of the Americas. Humboldt's influence is palpable in Rugendas's subsequent work. The artist increasingly sought to depict not just picturesque scenes, but the specific geological formations, vegetation types, and atmospheric conditions that defined a particular landscape. His approach blended the Romantic appreciation for the sublime and exotic with a commitment to empirical observation, aligning perfectly with Humboldt's vision of art as a companion to science.

This Humboldtian perspective distinguished Rugendas from many purely Romantic landscape painters of his time, such as his German contemporary Caspar David Friedrich, whose work focused more on spiritual symbolism and inner emotional states. While Rugendas certainly employed Romantic conventions – dramatic compositions, emphasis on vastness, fascination with the exotic – his art remained fundamentally grounded in the observable reality of the places he visited. This scientific underpinning would later inspire North American artists like Frederic Edwin Church, who followed Humboldt's and Rugendas's paths to South America decades later.

Journeys Across a Continent: Mexico, Chile, and Beyond

Inspired by Humboldt's encouragement and his own insatiable curiosity, Rugendas embarked on a second major American journey in 1831. This expedition would last for over a decade and take him through a vast swathe of the continent, from Mexico southward along the Andes. His goal, ambitious even by Humboldt's standards, was to create a comprehensive visual archive of the Americas, documenting the diverse landscapes and cultures from the tropics to the temperate zones.

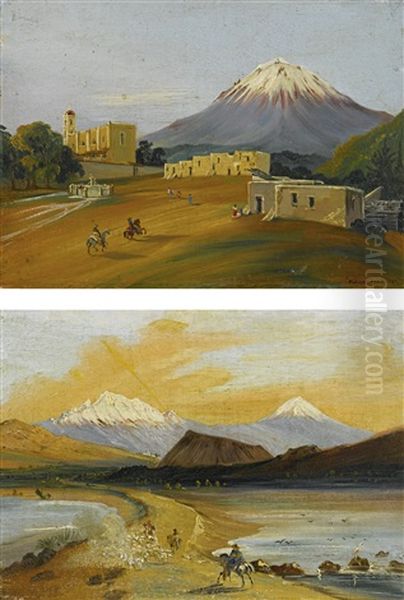

He spent several years in Mexico (c. 1831-1834), capturing its dramatic volcanic landscapes, colonial architecture, and vibrant street life. His Mexican works showcase his maturing style, combining detailed rendering with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere. From Mexico, he sailed south, arriving in Chile in 1834. The stark, dramatic scenery of the Andes and the distinctive culture of the Chilean heartland provided rich new subjects. He documented the lives of gauchos (known as huasos in Chile), indigenous peoples like the Mapuche (then often called Araucanians), and the landscapes stretching from the coast to the high mountains.

During his time in Chile, Rugendas sometimes worked alongside fellow German artist Robert Krause. Together, they sketched the Andean landscapes, though Rugendas remained the dominant figure. His Chilean period produced some of his most compelling ethnographic work, including sketches and paintings related to the Mapuche, such as the series depicting El Rapto (The Abduction), a theme reflecting contemporary conflicts and European perceptions of indigenous customs.

His travels continued southward into Argentina, likely crossing the Andes near Mendoza. It was during one such Andean crossing, around 1838, that Rugendas suffered a catastrophic accident. A fall from his horse resulted in a severe head injury, fracturing his skull and causing lasting neurological damage, including facial paralysis and possibly affecting his vision or motor control. This event marked a devastating setback in his ambitious project.

Resilience and Continued Travels

Despite the severity of his injuries and a long, difficult recovery period, Rugendas demonstrated remarkable resilience. The accident inevitably impacted his physical abilities and perhaps altered his artistic style, yet it did not end his determination to document the Americas. After recuperating, partly in Chile, he continued his travels, albeit perhaps at a slower pace.

Between 1842 and 1844, he journeyed through Peru and Bolivia. In Peru, he captured the unique atmosphere of Lima, including its famous tapadas limeñas – women veiled in a distinctive style – and the grandeur of the Andean highlands. His depictions of Lima's Plaza Mayor, for instance, blend architectural accuracy with observations of social life, continuing his practice of integrating human activity within specific environments. His interest in the tapadas has drawn comparisons to the observations of contemporary female traveler and writer Flora Tristan, both Europeans fascinated by this unique Lima custom.

He eventually made his way back towards the Atlantic coast, possibly passing through Argentina and Uruguay again, before finally sailing back to Europe in 1845, having spent nearly fifteen years continuously traveling and working in Latin America on this second major journey. He returned with an immense portfolio, thousands of sketches and studies documenting an astonishing range of landscapes and human experiences across the continent.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Observation and Romanticism

Rugendas's artistic style is characterized by a unique synthesis of detailed, almost scientific observation and the prevailing aesthetics of European Romanticism. His training provided him with a strong command of drawing and composition, evident in the clarity and structure of his works. His commitment to firsthand experience ensured a high degree of accuracy in his depictions of specific locations, botanical details, and ethnographic types.

His landscapes often convey a sense of grandeur and awe inspired by the vastness and untamed nature of the Americas. Works like Paisaje en la selva virgen (Landscape in the Virgin Forest) or studies of the Andes capture the dramatic scale and exoticism that fascinated European audiences. He employed light and shadow effectively to create atmosphere, sometimes heightening the drama of a scene in true Romantic fashion. This can be seen in contrast to the more detached, topographical style of some earlier expedition artists.

However, his Romanticism was tempered by the Humboldtian drive for accuracy. Unlike Eugène Delacroix, a leading French Romantic painter whose depictions of North Africa (based on a relatively short trip) emphasized intense color, dynamic movement, and overt emotionalism, Rugendas's work generally maintained a greater degree of descriptive realism. His color palette, particularly in his oil paintings, could be rich, but often aimed for naturalistic representation of local light and conditions.

His ethnographic work is similarly complex. He meticulously recorded the attire, tools, and physical features of various indigenous groups and local populations. Yet, these depictions are inevitably filtered through his European perspective and the artistic conventions of his time. While providing invaluable visual information, his portrayals sometimes verge on creating 'types' rather than individuals, a common practice in 19th-century ethnographic illustration.

Documenting Society: Slavery and Daily Life

A significant aspect of Rugendas's oeuvre is his documentation of social conditions, most notably the institution of slavery in Brazil. His Voyage Pittoresque includes numerous images depicting the lives of enslaved Africans – working on plantations, carrying goods in cities, suffering punishments, or gathered in their living quarters (Casa de negros). These images are among the most widely reproduced visual records of slavery in Brazil.

Art historians debate the intent and impact of these depictions. On one hand, they provide stark visual evidence of the brutality and pervasiveness of slavery. On the other hand, some critics argue that Rugendas's perspective remains that of an outside observer, occasionally aestheticizing or normalizing scenes of suffering through artistic composition. Compared to Jean-Baptiste Debret, whose images of slavery in Brazil are often seen as more overtly critical and emotionally charged, Rugendas's approach can appear more detached or ethnographic. Nonetheless, his visual record remains crucial for understanding the lived experience of slavery in 19th-century Brazil.

Beyond slavery, Rugendas captured a wide array of daily activities and social interactions in the cities and countryside. Market scenes, festivals, modes of transport, domestic interiors, and rural labor all feature in his work, providing a rich tapestry of life across different regions and social strata. His interest extended from the elite colonists to the marginalized indigenous and Afro-descendant populations, offering a remarkably broad, though not unmediated, view of Latin American societies.

Legacy and Collections

Upon his final return to Europe in 1847, Rugendas sought recognition and patronage for his vast body of work. He succeeded in selling a large portion of his American collection – over 3,000 pieces – to King Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1848. This collection now forms a core part of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung (State Collection of Graphic Arts) in Munich, making it a primary repository for Rugendas's drawings and watercolors.

Despite the significance of his work, Rugendas did not achieve the same level of fame within mainstream European art history as some of his contemporaries who focused on European subjects, like the German Romantics Friedrich or Carl Blechen. His specialization in Latin American themes placed him somewhat outside the central narratives of European art. However, his importance as a visual chronicler of Latin America is undisputed. His work provided Europeans with formative images of the continent and remains an invaluable resource for historians, anthropologists, and art historians studying the region's 19th-century history and culture. The Argentine writer and statesman Domingo Faustino Sarmiento famously remarked that only two Europeans truly understood America: Humboldt and Rugendas.

Today, besides the major collection in Munich, works by Rugendas can be found in various institutions worldwide. In Brazil, the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro and the Museu Paulista in São Paulo hold examples. German museums, including those in Berlin and his native Augsburg, also possess works. Some pieces, including letters, are held in archives like the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His paintings and prints occasionally appear in international exhibitions and auctions, reminding audiences of his unique contribution.

Conclusion: The Traveling Eye

Johann Moritz Rugendas was more than just a painter; he was an explorer, an ethnographer, and a visual historian. Driven by a combination of artistic ambition, scientific curiosity inspired by Humboldt, and an adventurous spirit, he dedicated decades of his life to documenting the landscapes and peoples of Latin America during a critical period of its history. His journey took him from the tropical rainforests of Brazil to the high Andes of Chile and Peru, facing personal hardship, including a life-altering injury, with remarkable tenacity.

His vast output, captured in thousands of drawings, watercolors, and paintings, provides an enduring legacy. While shaped by the perspectives and artistic conventions of his time, his work offers an unparalleled visual archive of 19th-century Latin America. He masterfully blended the observational rigor encouraged by Humboldt with the aesthetic sensibilities of Romanticism, creating images that are both informative and evocative. Rugendas remains a crucial figure for understanding not only the history of European art and exploration but also the complex visual representation of the Americas in the post-colonial world. His "picturesque voyages" continue to transport viewers to the continents he so meticulously observed and passionately rendered.