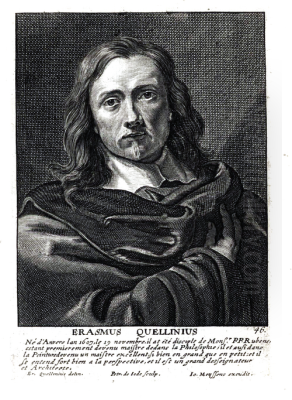

Introduction: An Artist Forged in Antwerp

Erasmus Quellinus II stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Flemish Baroque art. Born in Antwerp on November 19, 1607, he emerged from a family deeply rooted in artistic pursuits. His father, Erasmus Quellinus I, was a respected sculptor, and his brother, Artus Quellinus I, would also achieve fame as a sculptor, playing a key role in disseminating the Roman Baroque style in the Southern Netherlands. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured young Erasmus's artistic inclinations, although his initial education leaned towards the humanities and literature. Ultimately, the powerful draw of visual arts prevailed, setting him on a path to become one of Antwerp's most prominent painters, printmakers, and engravers of his generation. His life and career unfolded during a vibrant period for Antwerp's art scene, largely dominated by the towering figure of Peter Paul Rubens, with whom Quellinus would forge a crucial connection. He passed away in his native Antwerp on November 7, 1678, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a lasting legacy.

Early Life, Education, and the Influence of Rubens

Born into the artistic Quellinus dynasty, Erasmus II received a solid grounding in humanistic and literary studies. This intellectual background would later inform the learned subject matter and allegorical complexity found in some of his works. However, his primary calling was painting. The most decisive influence on his early artistic development was his association with Peter Paul Rubens. Quellinus became a student and, subsequently, a close collaborator in Rubens's highly productive workshop. This relationship began in earnest during the 1630s, a period when Rubens's studio was a powerhouse of artistic production, handling major commissions from across Europe.

Working alongside Rubens provided Quellinus with invaluable training and exposure to the master's dynamic Baroque style. He absorbed Rubens's approach to composition, colour, and dramatic narrative. Evidence of their close collaboration includes Quellinus's involvement in large-scale projects directed by Rubens, such as the decorations for the Triumphal Entry of the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand into Antwerp in 1635, documented in the publication known as the Pompa Introitu. Quellinus executed designs based on Rubens's sketches for this significant event. He also participated in painting parts of Rubens's mythological series commissioned for the Torre de la Parada, Philip IV of Spain's hunting lodge near Madrid. His painting, The Triumph of Bacchus (circa 1635-1638), created during this period, clearly demonstrates his assimilation of Rubens's vigorous style and thematic concerns.

The Development of a Personal Style: Baroque Meets Classicism

While deeply influenced by Rubens, Erasmus Quellinus II was not merely an imitator. Following Rubens's death in 1640, Quellinus emerged as one of the leading painters in Antwerp, inheriting, in a sense, the mantle of the city's foremost history painter. It was during this period, starting from the 1630s when he began working independently, that he started to forge his own distinct artistic identity. His style represents a fascinating synthesis of prevailing artistic currents.

His early works show an awareness of the dramatic chiaroscuro associated with Caravaggio and his followers, employing strong contrasts between light and shadow to heighten emotional intensity and model form. This interest in dramatic lighting remained a feature of his work, lending his figures a tangible presence. Quellinus developed a remarkable ability to imbue his painted figures with a sense of volume and weight, often described as sculptural. This was achieved partly through his sophisticated use of light and shade, and potentially influenced by his family background in sculpture. He was known to utilize grisaille techniques, monochrome paintings often used as studies or to mimic sculpture, further enhancing this sculptural quality and lending a naturalistic feel to his figures.

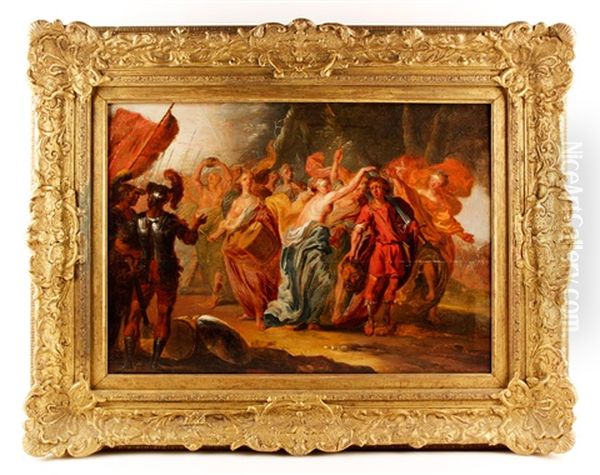

As his career progressed, particularly after Rubens's death, Quellinus's style evolved. While retaining the dynamism and richness of the Flemish Baroque, his work increasingly incorporated elements of Classicism, which was gaining traction in Antwerp. This shift is characterized by clearer compositions, more restrained emotions, cooler palettes, and an emphasis on graceful lines and idealized forms, often set against classical architectural backdrops. This blend of Baroque energy and Classical order became known as the distinctive "Quellinus style," marking him as a key proponent of the later, more classically-inflected phase of Flemish Baroque painting.

Versatility in Subject and Medium

Erasmus Quellinus II demonstrated remarkable versatility throughout his career, tackling a wide range of subjects and working across different media. His primary focus was history painting, encompassing religious, mythological, and historical narratives. He produced numerous altarpieces for churches and religious institutions in Antwerp and beyond. Notable examples include The Consecration of the Eucharist, reportedly created for the Lippert Palace in 1646, and the large-scale Immaculate Conception housed in St. Michael's Church in Luxembourg (measuring 500 x 287 cm). His earliest known dated work, The Adoration of the Shepherds from 1632, already hints at his capabilities in handling complex religious scenes.

Mythological themes also feature prominently in his oeuvre, often drawing from Ovid's Metamorphoses or other classical sources. These works allowed him to explore dynamic compositions and the idealized human form, often continuing the tradition established by Rubens. An example mentioned, though potentially requiring clarification on the title, is a work from 1640, possibly Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes, created in collaboration with his brother, the sculptor Artus Quellinus I. This collaboration highlights the close artistic ties within the family.

Beyond large-scale paintings, Quellinus was also active as a designer. He created designs for tapestries, a highly prestigious and lucrative art form in the 17th century. His skills extended to printmaking and engraving, contributing to the dissemination of artistic ideas. Furthermore, he was involved in designing ephemeral decorations for public celebrations and ceremonies, such as the previously mentioned Pompa Introitu and the Theatrum pacis Hispano-Gallicanum, a temporary installation celebrating the peace treaty between Spain and France, later re-presented as Hymenaeus pacifier for the Antwerp City Hall. This breadth of activity underscores his central role in the artistic life of Antwerp.

Collaborations and Artistic Relationships

Collaboration was a common practice in the bustling Antwerp art world, and Erasmus Quellinus II engaged in several significant artistic partnerships. His most formative collaboration was undoubtedly with Peter Paul Rubens, serving as a key assistant in the master's workshop. This experience was fundamental to his training and early career trajectory. After Rubens's death, Quellinus stepped into the void, becoming one of the most sought-after artists for major commissions. An anecdote illustrating this transition involves the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand suggesting that Rubens's unfinished paintings, following his death, should be completed by his leading assistants, with Quellinus being assigned one of these works, as documented in a letter to King Philip IV of Spain.

Quellinus frequently collaborated with specialized painters, particularly still life and flower painters, to create works that combined their respective talents. His partnership with the Jesuit painter Daniel Seghers, a renowned flower painter, was particularly fruitful. At least twenty-eight collaborative works are documented, typically featuring a central religious or mythological scene painted by Quellinus, surrounded by an elaborate floral garland painted by Seghers. One such example is held in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. This type of devotional garland painting was highly popular.

He also maintained a close working relationship with another flower painter, Jan Philips van Thielen. They collaborated on numerous garland paintings, a partnership possibly strengthened by family ties, although the exact nature of this connection requires further clarification. These collaborations highlight the specialized nature of Antwerp's art market and Quellinus's ability to integrate his figural compositions seamlessly with the work of other masters. His brother, Artus Quellinus I, the sculptor, was another important collaborator, particularly on projects that combined painted and sculptural elements.

Competition and Standing Among Contemporaries

In the competitive art market of 17th-century Antwerp, Erasmus Quellinus II navigated relationships with numerous other talented artists. While his association with Rubens provided a significant advantage, he also faced competition after establishing his independent workshop. Following Rubens's death, he vied with other artists for prestigious commissions. His stylistic shift towards a more classical idiom might be seen, in part, as a response to changing tastes and the styles promoted by other contemporary artists active in Antwerp and the wider region.

The provided text mentions competition within the Antwerp art scene, specifically naming Quentin Matsys. Matsys, however, belongs to an earlier generation (late 15th/early 16th century), so direct competition seems unlikely; perhaps the name was intended to represent the established artistic traditions Quellinus was measured against. The text also mentions Johannes Vermeer as a competitor. This is historically problematic, as Vermeer was primarily active in Delft, Holland, and worked in a very different genre and style. While their periods overlapped, direct competition within the Antwerp market between Quellinus and Vermeer is not typically documented by art historians. It's possible the source text contained an inaccuracy, but adhering strictly to it, Vermeer is noted as a perceived competitor.

Despite any competition, Quellinus achieved considerable success and recognition. His status is further evidenced by the rich personal art collection he amassed by the time of his death. This collection included not only his own works but also paintings by masters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, works by various Italian masters, and sculptures by his brother Artus Quellinus I. Such a collection signifies his wealth, connoisseurship, and high standing within the artistic community. It also became a significant part of the inheritance passed down to his descendants.

Later Career, International Reach, and Legacy

Erasmus Quellinus II remained a highly productive and respected artist throughout his later career. After the death of Rubens, he arguably became the most important history painter working in Antwerp, securing numerous commissions for altarpieces, civic decorations, and private patrons. His reputation extended beyond the borders of the Southern Netherlands. His works found their way into collections in Spain and Portugal, reflecting the extensive trade and cultural links Antwerp maintained, particularly with the Iberian Peninsula.

A remarkable testament to his international reach is the presence of his work in the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The large altarpiece Saint Gregory of Nazianzus (San Gregorio Nacianceno), measuring an impressive 535 x 298 cm, located in the Cathedral of Lima, Peru, is considered a major work by Quellinus. The source text intriguingly notes this painting as potentially depicting the sale of art by Jesuit monks and mentions it as a unique example of a Flemish painting from the Rubens circle that was sent from Peru back to Spain for conservation, highlighting the complex journeys of artworks across continents during this period. Another work, Saint Gregory the Bishop, once attributed to Quellinus, was found in the Convent of San Roque in Cusco, Peru, although this attribution has apparently been revised. These examples underscore his role in the transatlantic art market.

Quellinus played a role in perpetuating artistic traditions through his students. His own son, Jan Erasmus Quellinus II, followed in his footsteps to become a notable painter, continuing the family's artistic dynasty into the next generation. Other documented pupils include Julius de Geest. The text also mentions Guillaume Forchoudt II as a student (and potentially as a son, though the Forchoudt family were primarily known as art dealers, suggesting a possible apprenticeship or marital link rather than direct descent). Through his workshop and students, Quellinus's style and techniques were disseminated further.

Erasmus Quellinus II died in Antwerp on November 7, 1678, at the age of 71. He left behind a significant artistic legacy, recognized as one of the most important Flemish artists of the 17th century. His ability to synthesize the dynamism of Rubens's Baroque with the elegance of Classicism created a distinct and influential style. His contributions spanned painting, design, and printmaking, enriching the cultural landscape of Antwerp and beyond. His works continue to be studied and admired in museums and collections worldwide, affirming his enduring importance in the history of art.