Eric Gill stands as one of the most significant, yet deeply complex, figures in twentieth-century British art and design. Born Arthur Eric Rowton Gill in Brighton on February 22, 1882, he died in Uxbridge on November 17, 1940. In his relatively short but intensely productive life, Gill excelled as a sculptor, engraver, typographer, and writer. His work is inextricably linked with the later phases of the Arts and Crafts movement, yet it also possesses a unique modernity. Gill sought to integrate art, life, work, and spirituality, developing a philosophy that permeated his diverse creations. However, his enduring artistic legacy is permanently shadowed by revelations about his disturbing personal life, forcing ongoing debates about the relationship between an artist's character and their work.

Gill's upbringing was steeped in nonconformist Protestantism; his father was a minister in a dissenting sect. This religious background, though later transformed by his conversion to Roman Catholicism, arguably instilled in him a lifelong preoccupation with spiritual matters and a tendency towards moral absolutism, albeit applied idiosyncratically. His early education showed artistic promise, leading him to study at the Chichester Technical and Art School before moving to London in 1900.

Initially, Gill pursued architecture, apprenticing with the ecclesiastical architects W. D. Caröe. However, he quickly found the routine of an architect's office unfulfilling. Drawn more to the hands-on creation of form and letter, he began attending evening classes in stonemasonry at Westminster Technical Institute and, crucially, calligraphy classes at the Central School of Arts and Crafts under the tutelage of Edward Johnston. Johnston, a pivotal figure often called the "father of modern calligraphy," profoundly influenced Gill, instilling in him a deep understanding of letterforms, their history, and the importance of clarity and craftsmanship. This training would form the bedrock of Gill's later typographic achievements.

The Call of Craft: Early Career and Ditchling

Dissatisfied with architecture, Gill abandoned his apprenticeship around 1903 to establish himself as a freelance letter-cutter, calligrapher, and monumental mason. His skill quickly gained recognition. He received commissions for inscriptions, memorials, and architectural lettering. His style emphasized clarity, strong forms, and a respect for the material, usually stone. This period saw him associate with figures connected to the Arts and Crafts movement, absorbing its ideals regarding the dignity of labour, the rejection of industrial mass production, and the integration of art into everyday life. Figures like William Morris, though deceased, cast a long shadow, and Gill interacted with contemporaries like Emery Walker and T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, key figures in the private press movement and proponents of craft ideals.

A significant turning point came in 1907 when Gill moved his growing family out of London to Ditchling, a village in Sussex. This move was partly motivated by a desire for a simpler, more integrated life closer to nature, a common theme among Arts and Crafts adherents. In Ditchling, Gill sought to create a community where art, craft, family life, and spirituality could coexist harmoniously. This utopian vision attracted other artists and craftspeople, leading to the formation of The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic in 1921, after Gill and his associates had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1913.

The Ditchling community became a hub of creative activity. Alongside Gill, key members included the printer Hilary Pepler (who ran the St Dominic's Press), the weaver Ethel Mairet, and later, the artist and poet David Jones, who became a close associate and apprentice of Gill's. The community aimed for a degree of self-sufficiency, combining craft production with small-scale farming. They produced handcrafted furniture, sculptures, engravings, textiles, and printed matter, all guided by principles that valued handwork over mechanization and sought a spiritual dimension in creative labour. Gill's own output during this period was prolific, encompassing stone carving, wood engraving, and the beginnings of his typographic work.

Master of Stone: Gill's Sculpture

Sculpture, particularly direct carving in stone, was central to Gill's artistic identity. Influenced by medieval carving, archaic Greek sculpture, Indian temple art, and the directness advocated by contemporaries like Jacob Epstein and Constantin Brancusi, Gill rejected the prevailing academic practice of modelling in clay for subsequent reproduction by assistants. He believed in the artist engaging directly with the material, allowing the form to emerge from the stone itself. His sculptural style is characterized by simplified forms, clear outlines, a certain linearity derived from his graphic work, and often, a blend of sensuousness and spiritual intensity.

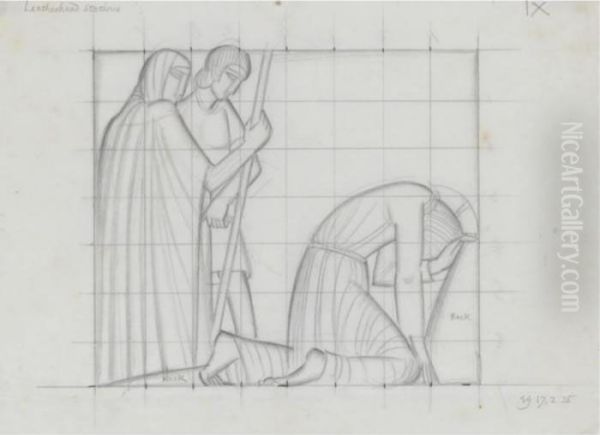

One of his earliest major sculptural commissions was the Stations of the Cross (1914-1918) for Westminster Cathedral in London. These fourteen low-relief panels, carved directly into the stone walls of the cathedral, demonstrate his ability to convey profound religious narrative through economical means. The figures are stylized, yet emotionally resonant, showcasing his distinctive blend of archaic and modern sensibilities. The directness of the carving and the integration with the architecture are hallmarks of his approach.

Perhaps his most famous, and later most controversial, public sculpture is Prospero and Ariel (1931), located above the entrance to the BBC's Broadcasting House in London. Depicting characters from Shakespeare's The Tempest, the work's stylized nudity and the relationship between the figures generated debate even at the time. Gill intended it to symbolize the magic of broadcasting. Its prominent location has made it a focal point for protests in recent years, following the wider publicization of Gill's sexual abuse.

Other significant sculptural works include Mankind (1927-28), a powerful torso carved in Hoptonwood stone, now in the Tate collection, which shows the influence of non-European sculpture. He also created numerous religious figures, war memorials (such as the Trumpington War Memorial near Cambridge), and architectural carvings. His work for the League of Nations building in Geneva, including the relief Adam and Eve (1938), further cemented his international reputation as a sculptor. Throughout his sculptural career, Gill explored themes of creation, spirituality, the human body, and the integration of art and architecture.

The Printed Word: Typography and Engraving

While Gill considered himself primarily a sculptor, his impact on typography and graphic arts is arguably even more widespread and enduring. Building on the foundation laid by Edward Johnston, Gill brought his sculptor's sensibility for form and his calligrapher's understanding of letter structure to the design of typefaces. His collaboration with Stanley Morison, the influential typographic advisor to the Monotype Corporation, was particularly fruitful.

The most famous result of this collaboration is the Gill Sans typeface family. Commissioned by Morison and released by Monotype between 1928 and 1930, Gill Sans was based on the lettering Gill had developed, which itself was derived from Johnston's sans-serif typeface designed for the London Underground. Gill Sans, however, possessed a greater range of weights and a subtle classical feel, often described as a "humanist" sans-serif. Its clarity, versatility, and modern yet traditional character led to its rapid adoption across British visual culture. It became the standard typeface for the LNER railway company, was famously used by Penguin Books for their iconic covers, appeared on BBC materials, and countless other applications. It remains one of the most recognizable and widely used typefaces of the 20th century.

Gill did not stop with Gill Sans. He designed several other important typefaces for Monotype, including Perpetua (released 1929), a beautiful and refined serif face inspired by Roman inscriptions, complete with its elegant italic companion, Felicity. Joanna (designed 1930-31, released 1937), named after one of his daughters, is another distinctive serif typeface, originally used for his own book An Essay on Typography. He also designed the Golden Cockerel Roman (1929) for the private press of the same name. These typefaces demonstrate Gill's mastery of letterforms, combining historical understanding with a modern clarity.

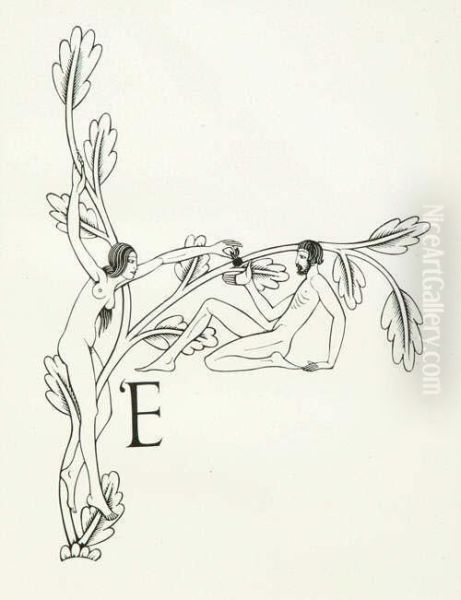

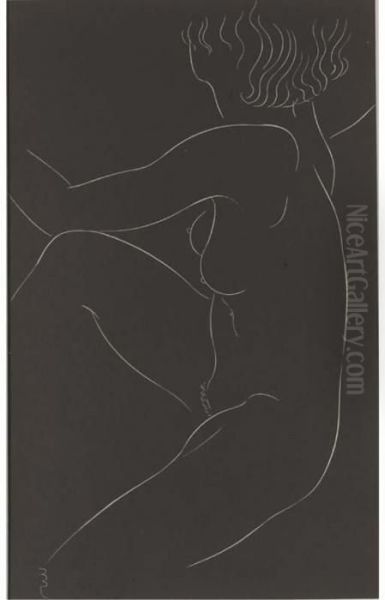

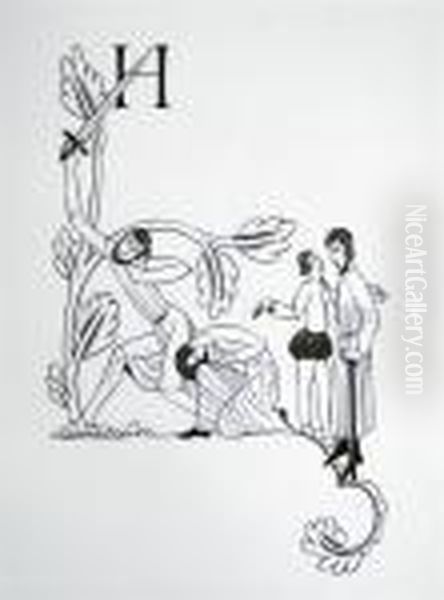

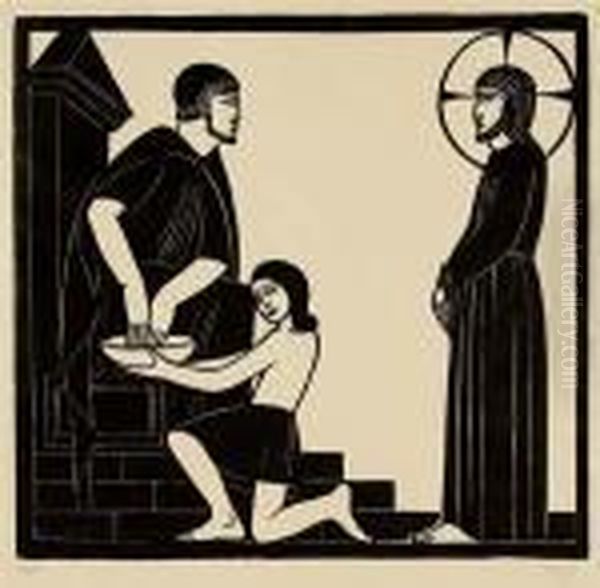

Beyond type design, Gill was a prolific wood engraver. His engravings often complemented his work in other media, appearing as illustrations in books printed by the St Dominic's Press, the Golden Cockerel Press (run by Robert Gibbings), and other publishers. His style is characterized by clean lines, strong contrasts of black and white, and often, a focus on the human figure, frequently nude. Religious themes intertwine with sensual and sometimes explicitly erotic imagery, reflecting his complex personal philosophy.

Notable examples of his engraved work include the illustrations for The Four Gospels (Golden Cockerel Press, 1931), considered a masterpiece of private press printing, where his engravings integrate seamlessly with his Golden Cockerel typeface. He also illustrated editions of The Canterbury Tales and produced numerous independent prints, such as the series Twenty-Five Nudes (1938). His bookplates, like the one designed for the poet Alice Meynell, are also highly regarded. The influence of artists like William Blake can sometimes be discerned in the linear quality and visionary intensity of his engravings, though Gill's style remains distinctly his own.

Writings, Philosophy, and Contradictions

Eric Gill was not only a maker but also a thinker and a prolific writer. He produced numerous essays, pamphlets, and books articulating his views on art, craft, society, religion, work, and sexuality. His writing style was often polemical, direct, and provocative. Key works include Art Nonsense and Other Essays (1929), Beauty Looks After Herself (1933), An Essay on Typography (1931), and his posthumously published Autobiography (1940).

Central to Gill's philosophy was the idea of integration. He railed against the fragmentation of modern life, particularly the separation of the artist from the craftsperson, work from life, and the spiritual from the material (and sexual). He believed that work should be meaningful and fulfilling, ideally involving handcraft. He saw the industrial system as dehumanizing and destructive of true culture. His conversion to Catholicism provided a framework for his ideas, though his interpretation was often unconventional. He aligned himself with some aspects of Distributism, a socio-economic philosophy championed by G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, which advocated for small-scale property ownership and localized economies.

Gill argued passionately for the importance of the "thinginess" of things – the inherent quality and integrity of objects made with skill and care. He believed that beauty was not merely subjective but related to the proper making of an object according to its nature and purpose. In An Essay on Typography, he famously stated, "Letters are things, not pictures of things," emphasizing their functional and structural reality.

However, Gill's philosophy also extended into deeply problematic territory, particularly concerning sexuality. He viewed sexual activity as a natural, God-given good, integral to human wholeness and even spirituality. While this challenged puritanical attitudes, his personal application of these ideas, as revealed in his private diaries, involved shocking transgressions. His writings often contain passages celebrating the body and sexuality in ways that, in retrospect, seem disturbingly self-justifying given his actions. The stark contradiction between his devout religious pronouncements and his abusive behaviour remains the most challenging aspect of his life and work.

Contemporaries and Collaborations

Gill's career intersected with many key figures in British art and design. His relationship with Edward Johnston was foundational. His work within the Arts and Crafts milieu brought him into contact with T.J. Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker. His Ditchling community involved close collaboration with Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute, and provided mentorship to David Jones, who developed his own unique artistic path but remained deeply influenced by Gill.

In the world of typography, his collaboration with Stanley Morison at Monotype was crucial for the production and dissemination of his most famous typefaces. He worked closely with printers like Robert Gibbings of the Golden Cockerel Press. As a sculptor, he was a contemporary of Jacob Epstein, whose work often shared a similar vitality and engagement with direct carving, though their styles differed. While Gill admired the work of continental modernists like Aristide Maillol, whom he met, his own aesthetic remained rooted in a blend of tradition and a specific, often English, form of modernism.

He was aware of, and sometimes critical of, other artistic currents. He had early associations with figures around Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury group but later distanced himself from their aesthetic theories. He stood apart from the more radical abstraction of artists like Ben Nicholson or the Vorticism of Wyndham Lewis, maintaining a commitment to figuration and craft-based practices. His unique position, bridging craft traditions and modern design, makes him a fascinating figure within the landscape of early 20th-century British art.

The Shadow of Controversy

The posthumous publication of Gill's diaries, and particularly the detailed account in Fiona MacCarthy's 1989 biography, brought the disturbing aspects of his private life into public view. The diaries documented his incestuous relationships with his sisters and daughters, and sexual experimentation that included bestiality. These revelations cast a dark shadow over his artistic achievements and his carefully constructed public persona as a devout Catholic craftsman.

The disclosures ignited fierce debate about how, or even if, one should separate the art from the artist. Can work promoting spiritual values or aesthetic harmony be appreciated when created by someone who committed such profound moral transgressions? How does the knowledge of the abuse affect the interpretation of his frequently sensual or erotic imagery, particularly depictions of his own family members?

There are no easy answers. Some argue for a clear separation, judging the work solely on its aesthetic merits and historical significance. Others find it impossible to view the work, especially pieces with religious or familial themes, without the taint of the artist's actions. Public institutions holding his work have had to grapple with how to present it, often including contextual information about his life. The controversy resurfaces periodically, as seen in the vandalism of the Prospero and Ariel sculpture at the BBC and subsequent calls for its removal. Gill's life forces a confrontation with the uncomfortable complexities that can exist between artistic genius and personal morality.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the profound controversies, Eric Gill's influence on 20th and 21st-century art and design is undeniable. His typefaces, particularly Gill Sans, remain ubiquitous, embedded in the fabric of visual communication. Perpetua and Joanna also continue to be respected and used. His contribution to typography lies in his ability to create letterforms that were both modern and rooted in historical understanding, functional yet aesthetically pleasing.

As a sculptor and engraver, his emphasis on direct carving and clear form influenced subsequent generations of British artists and craftspeople working in stone and wood. His integration of lettering into sculptural and architectural work set a high standard. Figures like Reynolds Stone carried forward aspects of his engraving and letter-cutting tradition.

His role in the Arts and Crafts movement, particularly through the Ditchling experiment, highlights the enduring appeal of integrating art, craft, and life, even if his own community ultimately fractured. He remains a key figure in the history of that movement's later development and its intersection with modernism and religious thought.

His writings continue to provoke thought about the nature of art, work, and society, even as they are read through the lens of his personal failings. He articulated a powerful critique of industrial society and a defence of skilled handwork that resonates with contemporary concerns about sustainability and meaningful labour.

Conclusion: A Complex Inheritance

Eric Gill remains a figure of profound contradictions. He was a master craftsman whose work championed clarity, order, and spiritual values. His contributions to sculpture, typography, and engraving significantly shaped British visual culture in the 20th century. Gill Sans alone secures his place in design history. He was also a charismatic, dogmatic, and influential thinker who sought to build a life where art and faith were seamlessly interwoven.

Simultaneously, he was a man whose private life involved appalling acts of sexual abuse and betrayal, documented in his own hand. This dark side irrevocably complicates his legacy. Evaluating Gill requires acknowledging both the brilliance of his artistic output and the gravity of his personal conduct. He leaves behind a body of work that continues to be used, admired, and debated, alongside a life story that serves as a stark and troubling case study in the complex relationship between creativity and human fallibility. His inheritance is rich, influential, and deeply, permanently unsettling.