Elie Nadelman stands as a pivotal, albeit sometimes underappreciated, figure in the narrative of early 20th-century sculpture. A Polish-born artist whose career gracefully spanned the cultural epicenters of Europe and the burgeoning modern art scene of the United States, Nadelman forged a distinctive visual language. His work is characterized by an elegant synthesis of classical aesthetics, particularly inspired by ancient Greek sculpture, and the streamlined sensibilities of modernism. This unique fusion allowed him to create sculptures that exude a timeless harmony while simultaneously engaging with contemporary life, profoundly influencing the trajectory of American sculpture.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Europe

Born Eliasz Nadelman in Warsaw, Poland, in 1882, into a middle-class Jewish family, his upbringing was imbued with an appreciation for art and music. This early cultural immersion undoubtedly shaped his aesthetic sensibilities. His formal artistic training commenced at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. While his time there was reportedly brief, it was here he encountered instructors like Konstantin Laszczka, a professor known for teaching a style derived from the impressionistic dynamism of Auguste Rodin. Though Nadelman might not have found Laszczka's approach entirely novel, the academic environment and the pervasive influence of Rodin—the colossus of late 19th-century sculpture—would have been inescapable and formative.

Driven by a burgeoning passion for classical art, Nadelman soon left Warsaw. He journeyed first to Munich in 1902, a city then rich in classical collections and a vibrant art scene, though perhaps more conservative than Paris. It was in Munich that his deep study of Greek sculpture, particularly the serene beauty of Praxitelean forms and the stylized elegance of Archaic figures, began to truly solidify the foundations of his artistic vision. He sought an art of pure form, of underlying geometric harmony, a stark contrast to the emotional turbulence often found in Rodin's work. Nadelman was less interested in capturing fleeting moments of passion and more in distilling the enduring essence of form.

The Parisian Crucible: Innovation and Recognition

Around 1904 or 1905, Nadelman moved to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. This was a period of intense artistic ferment, with Fauvism exploding onto the scene and Cubism gestating in the studios of artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Nadelman quickly immersed himself in this avant-garde milieu. He became a regular at the gatherings of the Parisian intellectual and artistic elite, frequenting the homes and studios of figures such as Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, whose salon was a meeting point for artists and writers. He established connections with luminaries including Picasso, Braque, Constantin Brancusi, Amedeo Modigliani, and the writer André Gide.

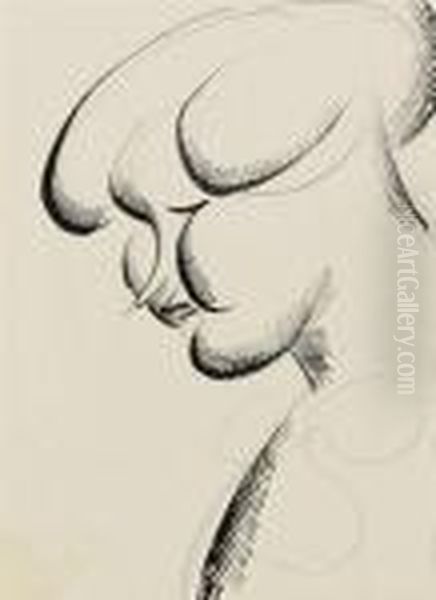

His own artistic voice began to mature rapidly. Nadelman's focus was on the "significant form," the idea that aesthetic emotion arises from the harmonious arrangement of lines and volumes. He articulated his theories in notes and aphorisms, emphasizing the importance of curvature and the interplay of convex and concave surfaces. His first major solo exhibition, held at the prestigious Galerie Druet in April 1909, was a resounding success. It featured a series of classical heads and figures in bronze and plaster, which, while rooted in antiquity, possessed a distinctly modern simplification and refinement. Critics lauded his work for its purity and elegance. Helena Rubinstein, the cosmetics magnate and an avid art collector, became an important early patron, acquiring numerous pieces from this show.

The relationship between Nadelman's work and the nascent Cubist movement is a subject of art historical discussion. Picasso himself reportedly acknowledged Nadelman's influence, particularly citing a Nadelman head as a stimulus for his own Cubist explorations around 1908. While Nadelman's pursuit of geometric simplification and volumetric clarity shared some common ground with Cubism, his artistic aims were different. He sought a harmonious synthesis and idealization, rather than the analytical deconstruction and fragmentation characteristic of Cubism. His work from this period, such as the serene marble heads, shows a profound understanding of classical principles filtered through a modern sensibility, often compared to the work of Aristide Maillol in its pursuit of tranquil monumentality. He also exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, further cementing his reputation.

Transatlantic Shift: Nadelman in America

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 compelled Nadelman to leave Europe. He immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City. America, and New York in particular, was on the cusp of becoming a new center for modern art, partly fueled by the influx of European artists fleeing the war. The controversial 1913 Armory Show had already introduced American audiences to European modernism, and Nadelman, with his established Parisian reputation, found a receptive environment.

He quickly became a significant figure in the American art scene. Alfred Stieglitz, a champion of modern art, gave Nadelman a solo exhibition at his renowned "291" gallery in 1915, which was met with critical acclaim. This was followed by another successful show at Scott & Fowles Gallery in 1917. Nadelman's work began to evolve, absorbing and reflecting aspects of American popular culture. He became fascinated by the vernacular arts, the dynamism of vaudeville, circus performers, and the elegant figures of contemporary society.

His sculptures from this period often depict dancers, acrobats, and society hostesses, rendered in materials like polished wood (cherry, mahogany, walnut), bronze, and even painted plaster or galvano-plastique (a form of electroplating). These works retained his signature elegance and refined curvilinear style but were imbued with a new sense of wit, urbanity, and sometimes a gentle satire. He married Viola Flannery, a wealthy American heiress, in 1919. Her financial resources provided him with stability and the means to pursue his artistic and collecting interests.

The Essence of Nadelman's Style: A Fusion of Influences

Nadelman's artistic style is a complex and sophisticated amalgamation of diverse influences, masterfully synthesized into a coherent and personal vision. At its core lies a profound reverence for classical Greek art. He admired its idealization of the human form, its emphasis on balance, harmony, and the perfect interplay of curves. This classical foundation provided his work with a sense of timelessness and formal rigor. Unlike the more academic classicists, however, Nadelman did not merely imitate ancient models; he reinterpreted them through a modern lens.

His modernism manifested in his radical simplification of form, his emphasis on smooth, polished surfaces, and his distillation of figures to their essential geometric underpinnings. There's a distinct Art Deco sensibility in many of his American-period works – a sleekness, an elegance, and a decorative quality that resonated with the aesthetics of the 1920s and 30s. Artists like Constantin Brancusi and Alexander Archipenko were also exploring paths of sculptural simplification, though Nadelman's approach always retained a stronger connection to the human figure and a certain classical grace.

A crucial, and perhaps initially surprising, element in Nadelman's mature style was his deep appreciation for American folk art. He and his wife, Viola, became pioneering collectors of folk art, amassing an extensive collection of paintings, sculptures, textiles, and decorative objects. Nadelman recognized the inherent aesthetic quality in these often-anonymous creations – their directness, their unpretentious charm, and their intuitive sense of design. He saw in folk art a purity and an honesty that he sought to emulate in his own sophisticated work. This influence can be seen in the stylized naivety of some of his figures, their doll-like qualities, and their often playful or whimsical character.

His choice of materials was also integral to his style. He worked masterfully in traditional materials like marble and bronze, achieving exquisite patinas and polished surfaces. However, he was particularly innovative in his use of wood, often cherry or walnut, which he carved and polished to a high sheen, emphasizing the natural grain and warmth of the material. He also experimented with painted wood and plaster, and the less common technique of galvano-plastique, creating hollow metal forms that were lighter and less expensive than cast bronze.

Key Works and Their Significance

Nadelman's oeuvre includes several iconic pieces that encapsulate his artistic vision.

Man in the Open Air (c. 1915), a sleek bronze figure, is perhaps one of his most famous American works. With its bowler hat, stylized suit, and gracefully attenuated limbs, it embodies a modern, urban dandy, yet its contrapposto pose and idealized features echo classical statuary. It has a distinct Art Deco elegance and a subtle, almost melancholic, charm.

His Dancer and Tango figures (various dates, c. 1918-1925), often carved in wood, capture the fluidity and rhythm of movement. These sculptures are characterized by their smooth, flowing lines and simplified, almost abstract, forms. The figures are often androgynous, their bodies reduced to elegant curves and counter-curves, conveying the essence of dance rather than a specific anatomical representation. Works like Kneeling Dancer (or Dancing Figure) showcase this refined abstraction and graceful poise.

The classical heads Nadelman produced, particularly during his Parisian period but also later, are masterpieces of serene beauty. Carved in marble or cast in bronze, works like Head of a Woman (c. 1909-1911) demonstrate his ability to evoke a sense of timeless perfection through subtle modeling and an exquisite understanding of volume and line. These heads often have a meditative, introspective quality.

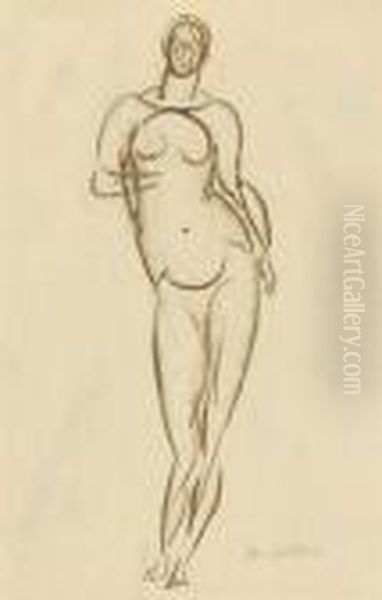

Later works, such as Hostess (c. 1920s) or Two Women (c. 1930s), often made of painted wood or plaster, reflect his engagement with contemporary society and his interest in folk art. These figures can be witty, sometimes satirical, portrayals of social types, rendered with a sophisticated naivety. Man in a Top Hat (c. 1927) is another example of this urbane subject matter, blending classical simplification with a modern, almost cartoonish, elegance. His Standing Female Nude sculptures, from various periods, consistently demonstrate his commitment to the idealized human form, reinterpreted through his evolving stylistic lens.

The Nadelman Museum of Folk Arts

Elie and Viola Nadelman's passion for folk art culminated in the establishment of the Museum of Folk Arts in Riverdale, New York, in 1926. Housed in a building on their estate, it was one of the first museums in the United States dedicated exclusively to folk art. Their collection was vast and diverse, encompassing American and European folk paintings, sculptures, weather vanes, ship figureheads, chalkware, textiles, and household objects.

Nadelman meticulously arranged the displays, emphasizing the aesthetic qualities of the objects rather than their purely historical or anthropological significance. He believed that folk art possessed a "purity of plastic vision" and an "instinctive understanding of form" that was often lost in more academic art. The museum was a testament to his belief in the artistic value of these vernacular traditions and played a significant role in fostering a wider appreciation for folk art in America. Artists like Joseph Cornell and H.C. Westermann, who later incorporated folk and vernacular elements into their own work, would have found resonance in Nadelman's advocacy.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression had a devastating impact on the Nadelmans' finances. They were forced to sell their vast folk art collection in 1937, much of it acquired by the New-York Historical Society. The closure of the museum was a significant loss, but its pioneering spirit had already left an indelible mark on the American art world.

Later Years, Seclusion, and Posthumous Recognition

The financial ruin brought on by the Depression, coupled with a sense of disillusionment with the art world, led Nadelman to withdraw increasingly from public life. From the early 1930s until his death, he largely ceased exhibiting his work. He continued to sculpt, but his focus shifted to smaller, more intimate figures, often in plaster or terracotta. These late works, hundreds of them, were largely unknown to the public. They often depicted doll-like female figures, sometimes in pairs or groups, possessing a fragile, almost ethereal quality.

Nadelman became reclusive, working in isolation in his Riverdale studio. He reportedly felt that the art world had moved in directions he did not appreciate, perhaps finding the rise of abstract expressionism and other more radical forms of modernism alien to his own classically-inflected sensibilities. On December 28, 1946, Elie Nadelman died by suicide in his studio. The reasons were likely complex, stemming from financial hardship, professional isolation, and perhaps a profound sense of artistic loneliness.

After his death, the hundreds of small plaster figures were discovered in his studio. This "lost" body of work, along with his earlier, more recognized sculptures, began to attract renewed attention, thanks in part to the efforts of figures like Lincoln Kirstein, a co-founder of the New York City Ballet and an admirer of Nadelman's work. Kirstein was instrumental in organizing posthumous exhibitions and publications that helped to re-evaluate Nadelman's contribution to modern art.

Nadelman's Enduring Legacy and Influence

Elie Nadelman's legacy is that of an artist who successfully navigated the complex currents of early 20th-century art, forging a unique path between the reverence for classical tradition and the innovative spirit of modernism. He was a sculptor of immense refinement and technical skill, whose work consistently prioritized elegance, harmony, and the expressive power of the curvilinear line.

His influence on American sculpture was significant, particularly in promoting a more stylized and formally sophisticated approach to the human figure. He can be seen as a precursor to certain aspects of Art Deco sculpture and as a contemporary who shared a refined aesthetic with artists like Gaston Lachaise, Robert Laurent, and William Zorach, all of whom contributed to the development of American modernist sculpture. While he did not have a large school of direct followers, his emphasis on craftsmanship and his sophisticated fusion of historical and modern sources provided an important model. Chaim Gross, for instance, studied briefly with Nadelman at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and went on to become a notable sculptor in his own right.

Nadelman's pioneering interest in folk art also had a lasting impact, contributing to its recognition as a legitimate and vital field of artistic expression. His ability to see the aesthetic connections between the "high" art of classical antiquity and the "low" art of vernacular traditions was visionary.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Elie Nadelman remains a compelling figure in the history of modern sculpture. His journey from Warsaw to Paris and then to New York mirrors the shifting centers of artistic gravity in the early 20th century. He absorbed diverse influences—from the serene perfection of Greek statues and the dynamism of Rodin, to the avant-garde experiments of Picasso and Braque, and the unpretentious charm of American folk art—and synthesized them into a singular, elegant, and enduring artistic vision. His sculptures, whether the polished bronzes, the warm woods, or the delicate late plasters, speak to a lifelong quest for an art of pure form, timeless beauty, and subtle wit. Though his later years were marked by seclusion and tragedy, the body of work he left behind continues to affirm his status as a master of refined modernism and a crucial bridge between European artistic traditions and the evolving landscape of American art.