Georges Lacombe (1868-1916) stands as a distinctive, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A painter and, more uniquely within his circle, a gifted sculptor, Lacombe was a dedicated member of the Nabis, a group of avant-garde Post-Impressionist artists who sought to imbue art with spiritual meaning and decorative beauty. His journey from a privileged upbringing to a key participant in one of art history's influential movements, his pioneering work in sculpture, and his deeply personal artistic vision make him a fascinating subject for study.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Versailles

Born in Versailles into a distinguished and financially comfortable family, Georges Lacombe's early life provided a fertile ground for artistic development. His mother, Laure Lacombe, was herself a painter and provided his initial instruction, nurturing his nascent talent from a young age. This familial support was crucial, offering him the freedom to pursue an artistic career without the immediate financial pressures that plagued many of his contemporaries.

To formalize his training, Lacombe enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris. This private art school was a popular alternative to the more rigid, state-run École des Beaux-Arts, attracting a diverse array of students, including many who would go on to become leading figures in modern art. At the Académie Julian, Lacombe studied under the guidance of established Impressionist masters Alfred Roll and Henri Gervex. While Impressionism's focus on light and fleeting moments would not define Lacombe's mature style, the technical skills and understanding of color he gained there were foundational.

It was also at the Académie Julian, or within its orbit, that Lacombe began to connect with a new generation of artists who were questioning the tenets of Impressionism and seeking fresh modes of expression. He formed important early relationships with figures like Émile Bernard and, crucially, Paul Sérusier. These encounters would prove pivotal in shaping his artistic direction and leading him towards the Nabis brotherhood.

The Nabis Brotherhood and the Embrace of Symbolism

The late 1880s and early 1890s were a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris. Paul Gauguin's work in Pont-Aven, with its emphasis on simplified forms, bold, non-naturalistic color, and spiritual content (Synthetism), had a profound impact on a group of younger artists. Paul Sérusier, after a revelatory painting session with Gauguin in 1888 where he produced "The Talisman," returned to Paris and became a catalyst for the formation of Les Nabis (from the Hebrew word for "prophets").

Lacombe officially joined this esoteric and enthusiastic group around 1892, following his significant meeting with Sérusier. The Nabis, including artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and Félix Vallotton, shared a desire to move beyond the surface appearances of the world. They were interested in suggestion, emotion, and the spiritual, often drawing inspiration from Symbolist literature, mysticism, and Japanese art. They believed art should be decorative and integrated into life, leading them to explore various media beyond easel painting, including stained glass, tapestries, and stage design.

For Lacombe, the Nabis' philosophy resonated deeply. He embraced their Symbolist leanings, which sought to convey ideas and emotions through indirect means, using forms and colors as symbols rather than for purely descriptive purposes. This intellectual and spiritual environment encouraged experimentation and a departure from academic conventions.

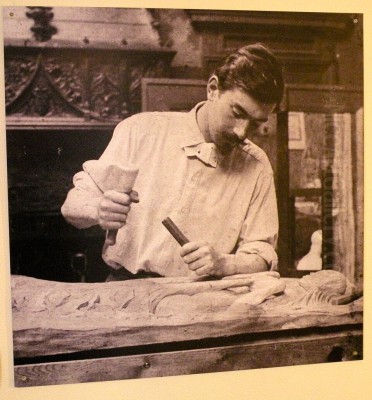

"Le Nabi Sculpteur": A Pioneer in Wood

Perhaps Lacombe's most distinctive contribution to the Nabis movement, and indeed to the art of the period, was his work in sculpture, particularly wood carving. While other Nabis members, like Gauguin and Bernard, had experimented with sculptural forms, Lacombe dedicated himself to the medium with a unique intensity, earning him the moniker "le Nabi sculpteur" (the Nabi sculptor).

His shift towards wood carving began in earnest after his 1892 encounter with Sérusier and was further fueled by the Nabis' general interest in applied arts and "primitive" forms. Lacombe was drawn to the directness of carving, the tactile quality of the wood, and the way it allowed for a simplification of form that aligned with Nabis aesthetics. He often used local woods like walnut, oak, or linden, and his technique involved direct carving, allowing the character of the wood itself to influence the final piece.

His sculptural works often depicted human figures, sometimes with a mystical or allegorical quality. One of his most celebrated pieces is "Breton Dancers" (Danseuses Bretonnes, 1893-1894), a carved wooden bedstead panel. This work exemplifies his style: simplified, somewhat archaic figures with a rhythmic quality, imbued with a sense of timeless ritual. The forms are robust and expressive, capturing the spirit of Breton culture, a region that held a strong allure for many Nabis artists, including Gauguin and Sérusier, due to its perceived authenticity and ancient traditions.

Other significant sculptural works include reliefs and freestanding pieces that often explore themes of life, death, and spirituality, reflecting the Symbolist preoccupation with the inner world. His approach was often characterized by a deliberate roughness or "primitivism," rejecting the polished academic finish in favor of a more expressive and emotionally direct statement. This aligned with a broader late 19th-century interest in non-Western and folk art, seen also in the work of artists like Gauguin.

Lacombe's Painted Visions: Symbolism and Japonisme

While renowned for his sculpture, Georges Lacombe was also a dedicated painter. His painted oeuvre, though perhaps less voluminous or widely known during his lifetime than his carvings, is integral to understanding his artistic vision. His paintings share the Symbolist and Nabis characteristics found in his three-dimensional work: a focus on mood, simplified forms, and often a decorative quality.

A significant influence on Lacombe's painting, as with many of his Nabis colleagues and other avant-garde artists of the era like Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas, and Mary Cassatt, was Japanese ukiyo-e prints. The principles of Japonisme – asymmetrical compositions, flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and decorative patterning – are evident in many of his works. This is particularly noticeable in his landscapes and seascapes.

"Blue Seascape: Effect of Wave" (Marine bleue, Effet de vagues, c. 1893) is a prime example. Here, Lacombe uses undulating lines and a limited, evocative palette to capture the rhythmic movement of the sea. The perspective is often high, almost a bird's-eye view, and the composition is stylized, emphasizing pattern and mood over literal representation. This work, like others depicting the coasts of Brittany or Normandy, showcases his ability to distill the essence of nature into a poetic and symbolic image.

His landscapes often feature simplified trees and landforms, rendered in broad areas of color. "Red Pines" (Pins rouges, 1894-1895) demonstrates his use of strong, sometimes non-naturalistic color to convey emotion and create a decorative effect. The influence of Gauguin's Synthetism, with its emphasis on memory, imagination, and the synthesis of form and color, is apparent.

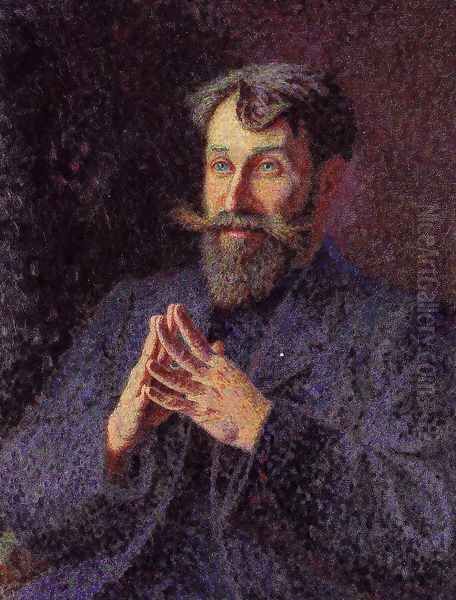

Lacombe also painted figurative works and portraits. "Portrait of Paul Ranson" captures a fellow Nabi, while other works, like "Chestnut Gatherers" (also known as "Autumn: Chestnut Gatherers"), depict scenes of rural life, often imbued with a sense of quiet dignity and timelessness. These works, while rooted in observation, transcend mere genre scenes through their simplified forms and symbolic undertones. Other notable paintings include "Violet Wave" (Vague violette), "Felled Tree, Normandy" (Arbre abattu, Normandie), and "In the Thicket" (Dans le taillis). His work "Věky života" (Ages of Life, c. 1894), likely a more allegorical piece, further underscores his Symbolist inclinations.

Themes, Inspirations, and Artistic Circle

Brittany, with its rugged coastline, ancient traditions, and deeply religious populace, was a recurring source of inspiration for Lacombe, as it was for Gauguin, Sérusier, and Bernard. The region seemed to offer an escape from the perceived artificiality of modern Parisian life and a connection to more fundamental, spiritual truths. His depictions of Breton landscapes and people often carry a sense of mystery and solemnity.

Nature, in general, was a profound theme for Lacombe. Whether the forests of Normandy or the waves of the Atlantic, he approached the natural world not as a detached observer but as a participant seeking its underlying spiritual essence. His landscapes are rarely just topographical records; they are emotional and symbolic responses to the power and beauty of nature.

Lacombe's artistic circle was primarily defined by his Nabis colleagues. He shared a close bond with Paul Sérusier, the group's theorist, and Paul Ranson, at whose studio, "The Temple," the Nabis often gathered. He also maintained contact with Émile Bernard, whose early experiments with Cloisonnism alongside Gauguin were foundational to Synthetism. While perhaps not as intimately involved in the theoretical debates as Denis or Sérusier, Lacombe's commitment to the Nabis' ideals was unwavering, expressed primarily through his artistic practice.

His friendship with Paul Cézanne is also noteworthy. Though Cézanne's rigorous structural concerns were somewhat different from the more decorative and mystical leanings of the Nabis, the mutual respect between artists of different, yet equally revolutionary, inclinations highlights the interconnectedness of the Post-Impressionist landscape. Cézanne's emphasis on underlying geometric forms and his departure from traditional perspective certainly resonated with the broader avant-garde quest for new artistic languages.

A Reluctant Exhibitor: Recognition and Legacy

A peculiar aspect of Georges Lacombe's career was his reluctance to sell his works. Coming from a family of means, he did not depend on art sales for his livelihood. This financial independence allowed him immense artistic freedom but also contributed to his relative obscurity during his lifetime compared to some of his Nabis peers like Bonnard or Vuillard, who actively engaged with the art market.

He did exhibit occasionally, for instance, at the Salon des Indépendants and later at the Salon d'Automne, venues that were crucial for avant-garde artists to showcase their work outside the official Salon system. However, he kept a large portion of his output, particularly his paintings, in his studio.

It was largely posthumously that Lacombe's contributions began to receive wider recognition. A retrospective exhibition in Paris in 1924 helped to bring his work to greater public attention. However, it was arguably the major Nabis exhibitions, such as the one held in Paris in 1955, that truly began to situate his work within the broader context of the movement and highlight his unique role as "le Nabi sculpteur." His descendants played a significant role in preserving his oeuvre, with many works remaining in the family collection until a large part was organized and exhibited more widely from 1974 onwards.

Today, Georges Lacombe's works are held in important public collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, which has a significant collection of Nabis art. His pieces can also be found in various French provincial museums and in collections internationally, such as in Geneva and even as far as Indonesia, testifying to a growing appreciation of his distinct artistic voice.

His legacy lies in his successful fusion of Nabis aesthetics with the medium of sculpture, creating a body of work that is both formally innovative and spiritually resonant. His wood carvings, in particular, stand as important precursors to later developments in modern sculpture, which also embraced direct carving and "primitive" influences (one might think of artists like Constantin Brâncuși or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, though their paths were different). His paintings, with their Symbolist depth and Japoniste elegance, further enrich our understanding of the diversity within the Nabis movement.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Georges Lacombe's art offers a compelling window into the spiritual and aesthetic concerns of the Fin de Siècle. As a core member of the Nabis, he shared their desire to create an art that was more than mere representation, an art that could touch the soul and beautify life. His unique dedication to sculpture set him apart, demonstrating the Nabis' commitment to breaking down hierarchies between fine and applied arts.

His deep connection to nature, particularly the landscapes of Brittany and Normandy, his absorption of Japanese artistic principles, and his Symbolist sensibility all converged to create a body of work that is both poetic and profound. While he may not have sought the limelight during his lifetime, the quiet intensity and innovative spirit of his paintings and sculptures ensure Georges Lacombe's enduring place in the narrative of modern art, a testament to a singular vision pursued with integrity and passion. His work continues to speak to us of a world imbued with mystery, beauty, and a deep, abiding spirituality.