Eric Ravilious stands as one of the most beloved and distinctive British artists of the first half of the 20th century. A master of watercolour, wood engraving, illustration, and design, his work captures a unique vision of England, blending a modernist sensibility with a deep affection for the nation's landscapes, traditions, and the quiet dramas of everyday life. His tragically short career, cut down during his service as a war artist in World War II, left behind a rich and varied body of work that continues to enchant and inspire. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Eric Ravilious, examining his key influences, collaborations, and his significant place within the tapestry of British art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Eric William Ravilious was born on July 22, 1903, in Acton, West London. His early years were marked by a family move to Eastbourne on the Sussex coast, a region whose chalky cliffs and rolling South Downs would later feature prominently in his art. His father, Frank Ravilious, was a draper, but the family faced financial difficulties, which perhaps instilled in young Eric a certain resilience and a keen observational eye for the world around him.

His artistic inclinations were evident early on, leading him to attend the Eastbourne School of Art from 1919 to 1922. His talent was undeniable, and in 1922, he secured a coveted scholarship to the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. This was a pivotal moment, placing him in an environment brimming with creative energy and influential figures. At the RCA, he studied in the Design School, where he honed his skills across various disciplines.

Crucially, it was at the RCA that he came under the tutelage of Paul Nash, a significant figure in British modernism and an accomplished landscape painter and war artist himself. Nash's influence on Ravilious was profound, not just in terms of technique but also in encouraging a modern, yet deeply personal, approach to landscape and design. Nash recognized Ravilious's unique talent, particularly his innate sense of pattern and his ability to imbue ordinary scenes with a subtle, almost surreal, quality.

The RCA also fostered lifelong friendships that would shape Ravilious's personal and professional life. Foremost among these was his bond with Edward Bawden, another exceptionally talented student who would become a distinguished painter, illustrator, and designer. Ravilious and Bawden shared a similar artistic temperament, a love for English vernacular, and a wry sense of humour that often permeated their work. Their friendship was a cornerstone of their respective careers, leading to numerous collaborations and shared artistic explorations. Other contemporaries who would make their mark included Henry Moore, then a sculpture student, and Barbara Hepworth, though Ravilious's closest artistic dialogues were with those more aligned with painting and design, such as Bawden and Enid Marx.

In 1924, Ravilious was awarded a travelling scholarship to Italy, visiting Florence, Siena, and other Tuscan towns. This experience exposed him to the masters of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the frescoes of artists like Giotto and Piero della Francesca. The clarity of composition, the use of flat perspective, and the narrative quality of these early Italian works resonated with Ravilious and subtly informed his developing style, particularly his approach to mural painting and large-scale compositions.

The Ascendance of a Printmaker: Wood Engravings and Illustrations

Upon completing his studies at the RCA in 1925, Ravilious began to establish himself as a professional artist. Wood engraving became one of his primary modes of expression during this period. The medium, revived in Britain by artists like Thomas Bewick in the late 18th century and further popularized by figures such as Eric Gill and Gwen Raverat in the early 20th century, suited Ravilious's meticulous nature and his gift for intricate design.

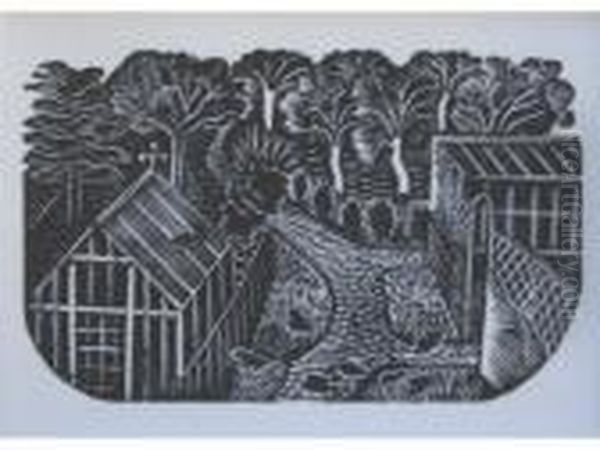

His wood engravings are characterized by their fine detail, elegant lines, and masterful use of black and white to create texture and atmosphere. He often employed a distinctive stippling or "punch" technique to achieve subtle tonal variations and a sense of light. His subjects ranged from pastoral scenes and architectural studies to more whimsical and narrative compositions.

A significant outlet for his talents in wood engraving came through commissions from private presses, most notably the Golden Cockerel Press. For them, he illustrated several books, including The Twelve Moneths by Nicholas Breton (1927) and, perhaps most famously, Gilbert White's The Natural History of Selborne (1938). His illustrations for Selborne are considered a triumph, perfectly capturing the spirit of White's observations of the English countryside. Ravilious's engravings for these volumes were not mere decorations but integral components that enhanced the reader's experience, demonstrating his deep understanding of the relationship between text and image.

He also produced wood engravings for the Lanston Monotype Corporation and for various other publications and commercial clients. His work in this field placed him among the leading British printmakers of his generation, alongside artists like Clare Leighton, Robert Gibbings, and his wife, Tirzah Garwood, herself a talented artist and engraver whom he married in 1930. Tirzah's own artistic pursuits and her understanding of the medium undoubtedly contributed to their shared creative world.

Beyond book illustration, Ravilious undertook mural projects, a notable example being the murals he and Edward Bawden painted for the refreshment room at Morley College in London between 1928 and 1930. Though tragically destroyed by bombing in 1941, contemporary accounts and surviving studies reveal a lively and imaginative scheme, showcasing their collaborative synergy and their ability to work on a large scale.

A Master of Watercolour: Capturing the English Psyche

While wood engraving established his reputation, it is perhaps for his watercolours that Eric Ravilious is most celebrated today. He brought a fresh, modern sensibility to this traditional British medium, developing a distinctive style that was both precise and evocative. His technique often involved a relatively dry brush, allowing for crisp lines and a clear articulation of form, reminiscent of the work of earlier English watercolourists like John Sell Cotman, yet entirely his own.

Ravilious's watercolours predominantly depict the English landscape, particularly the South Downs of Sussex and Wiltshire. He was drawn to the ancient chalk figures carved into the hillsides, such as the Long Man of Wilmington (1939) and the Westbury White Horse. These monumental forms, set against sweeping downland, are rendered with a sense of timelessness and a hint of the uncanny. His landscapes are rarely empty; they often feature signs of human presence – a fence, a path, agricultural machinery, or a distant building – but the figures themselves are usually absent or diminutive, emphasizing the scale and character of the land.

Works like Chalk Paths (c.1935), Downs in Winter (1934), and The Vale of the White Horse (1939) exemplify his ability to capture the unique light and atmosphere of the English countryside. There's a particular quality to his light – often cool, clear, and casting long, subtle shadows. He had an exceptional eye for the structure of the land, the patterns of fields, and the textures of natural and man-made objects. His compositions are carefully considered, often employing unusual perspectives or viewpoints that lend a slightly surreal or dreamlike quality to the scene, as seen in Train Landscape (1939-40), where the interior of a railway carriage frames the fleeting view outside.

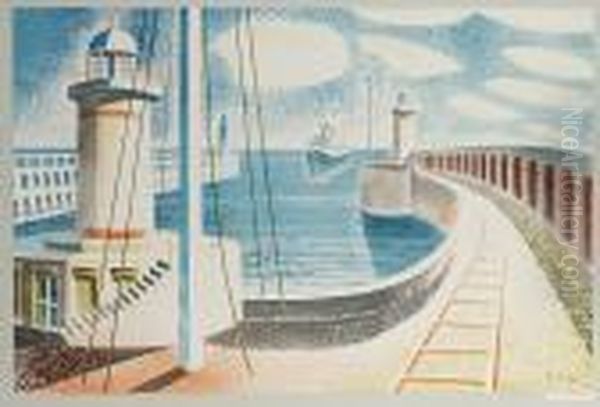

Ravilious also painted interiors, still lifes, and coastal scenes. Tea at Furlongs (1939) depicts the interior of the cottage in Sussex where he often stayed with Peggy Angus, another artist friend. The painting is a charming evocation of domestic simplicity, yet imbued with his characteristic clarity and design sense. His coastal scenes, such as Beachy Head Lighthouse (1939), capture the stark beauty of the English coastline with a similar precision and atmospheric sensitivity. These works often possess a quiet melancholy, a sense of England poised on the brink of change as war clouds gathered.

His watercolours were exhibited regularly, including solo shows at the Zwemmer Gallery in London (1933, 1936, and 1939), which helped to solidify his reputation. Critics and the public alike responded to the unique blend of tradition and modernity in his work, its quintessential Englishness, and its subtle emotional resonance. He was part of a generation of artists, including John Piper and Graham Sutherland, who were reinterpreting the British landscape tradition for a modern age, each in their own distinct way.

Design for Life: Wedgwood and Beyond

Eric Ravilious was a versatile artist who believed that good design should be part of everyday life. He embraced opportunities to work in applied arts, bringing his distinctive aesthetic to a wider audience. His most significant and enduring contribution in this field was his work for the Wedgwood pottery company.

In the 1930s, Wedgwood, under the enlightened leadership of Josiah Wedgwood V, sought to revitalize its ceramic designs by commissioning contemporary artists. Ravilious, along with Edward Bawden, was approached to create patterns for tableware and commemorative pieces. His designs for Wedgwood are a testament to his ingenuity and his ability to adapt his style to the specific demands of ceramic decoration.

Among his most famous Wedgwood designs is the "Alphabet" mug (1937), a charming piece featuring individual letters accompanied by whimsical illustrations. He also designed the popular "Boat Race Day" bowl (1938), and various dinner services with motifs like "Garden Implements," "Persephone" (also known as "Harvest"), and "Travel" (1950s, produced posthumously). These designs are characterized by their clarity, wit, and elegant linearity, perfectly suited to the ceramic forms.

Perhaps his most widely recognized Wedgwood piece is the Coronation Mug designed for the coronation of Edward VIII in 1937. When Edward abdicated, the design was swiftly adapted for the coronation of George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Its elegant silhouette and refined decoration, featuring fireworks and royal insignia, made it an instant classic. It was so successful that a version was reissued for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Beyond Wedgwood, Ravilious undertook other design commissions. He created advertisements and posters, including work for London Transport, though less extensively than contemporaries like Edward McKnight Kauffer or Barnett Freedman. He also designed book jackets and endpapers, always bringing a fresh and distinctive approach. His ability to move seamlessly between fine art and applied art was characteristic of a particular strand of British modernism that sought to break down the barriers between disciplines, a philosophy shared by artists associated with movements like the Omega Workshops (founded by Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant) and later, the artists of the Great Bardfield community in Essex, where Ravilious and Bawden, along with their wives Tirzah Garwood and Charlotte Bawden, lived for a period.

The Great Bardfield artists, including John Aldridge and later Michael Rothenstein, shared an interest in English vernacular traditions and a commitment to making art accessible. Ravilious's time there, particularly at Bank House and later Brick House with Tirzah, was productive and creatively stimulating, fostering an environment of mutual support and artistic exchange.

The War Artist: A New Canvas

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the course of Eric Ravilious's life and art took a dramatic turn. He was one of the first artists to be appointed as an official War Artist by the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC), chaired by Sir Kenneth Clark. This scheme aimed to create a comprehensive artistic record of the war, employing artists to depict all aspects of the conflict, both at home and on the various fronts.

Ravilious was assigned to the Admiralty as an Honorary Captain in the Royal Marines. His initial postings were to naval bases in Britain, including Chatham and Sheerness. He threw himself into this new role with characteristic diligence and enthusiasm, finding fresh subjects in the unfamiliar world of warships, submarines, and coastal defenses. His watercolours from this period are remarkable for their ability to capture the stark, functional beauty of naval vessels and the tense atmosphere of wartime Britain.

He produced a significant body of work depicting life in the Royal Navy. His Submarine Series (1940-41), painted during his time at HMS Dolphin in Gosport, offers a fascinating glimpse into the cramped and complex interiors of these underwater craft. Works like The Interior of a Submarine and Working Controls in a Submarine convey the claustrophobic environment and the intricate machinery with his typical precision and an almost surreal detachment. He found a strange beauty in the "mechanical beasts," as he sometimes referred to them.

Ravilious also depicted naval operations and coastal scenes. He painted convoys, mine-sweeping operations, and views from aircraft. His war art is not overtly heroic or propagandistic; rather, it is observational, imbued with a quiet intensity and a sense of the human element within the vast machinery of war. He travelled to various locations, including Scapa Flow in Scotland, Dover, and other coastal areas. In 1940, he was sent to Norway with the Royal Marines, an experience that yielded powerful images like Norway and Midnight Sun (1940), capturing the stark, alien landscapes of the Arctic campaign.

His war watercolours, such as HMS Ark Royal in Action (1940) and Dangerous Work at Low Tide, Rendering a Mine Safe (1940), are among the most memorable images produced by any British war artist. They demonstrate his ability to adapt his style to new and challenging subjects while retaining his unique artistic voice. The clarity of his vision, combined with a subtle sense of unease, perfectly encapsulated the atmosphere of a nation at war. His work, alongside that of other war artists like Paul Nash, John Piper, Graham Sutherland, Stanley Spencer, and Henry Moore, formed a vital part of Britain's cultural response to the conflict.

A Tragic End and an Enduring Legacy

In late August 1942, Eric Ravilious was posted to RAF Kaldadarnes in Iceland, again as a war artist, this time attached to RAF Coastal Command. His task was to document the activities of the squadrons involved in air-sea rescue and anti-submarine patrols in the North Atlantic. On September 2, 1942, he volunteered to accompany a crew on a patrol in a Lockheed Hudson aircraft. The plane failed to return from its mission. Despite extensive searches, no trace of the aircraft or its crew was ever found. Eric Ravilious was officially declared dead, presumed lost at sea, at the age of just 39.

His premature death was a profound loss to British art. He was at the height of his powers, an artist whose unique vision had already made a significant impact and who undoubtedly had much more to contribute. His wife, Tirzah Garwood, was left with their three young children: John, James (who would become a renowned photographer), and Anne.

In the decades following his death, Ravilious's reputation has steadily grown. While he was well-regarded during his lifetime, his work has achieved a new level of appreciation in recent years. Numerous exhibitions, including a major retrospective at the Imperial War Museum in 2003 (marking his centenary) and another at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2015, have introduced his art to new generations. Publications and documentaries have further illuminated his life and work.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent British artists who have been drawn to landscape, illustration, and design. Artists like David Gentleman, also a watercolourist and designer, have acknowledged his importance. The particular strain of English romanticism combined with a modernist clarity that Ravilious embodied continues to resonate. His ability to find beauty and intrigue in the ordinary, to capture the spirit of a place with such precision and subtle emotion, remains a hallmark of his art.

Eric Ravilious's legacy is multifaceted. He was a master watercolourist who redefined the possibilities of the medium for his time. He was a brilliant wood engraver and illustrator whose work graced some of the finest books of the period. He was an innovative designer who brought artistry to everyday objects. And he was a war artist whose unique perspective provided an invaluable record of a critical period in British history.

His art speaks of a deep love for England, but it is an England seen through a distinctly modern lens – an England of quiet beauty, subtle mysteries, and enduring character. His paintings and engravings evoke a sense of place that is both timeless and specific, capturing the fleeting moments and enduring landscapes that define a nation's identity. More than just a chronicler of his time, Eric Ravilious was an artist who shaped our vision of England itself, leaving behind a body of work that remains as fresh, engaging, and quintessentially English today as it was during his lifetime.