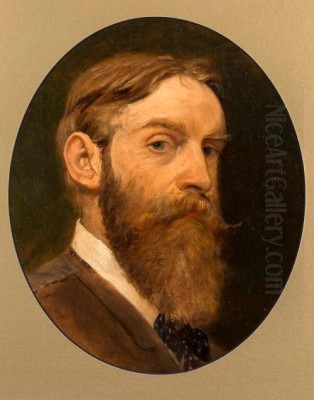

Randolph Caldecott stands as a monumental figure in the history of illustration, particularly in the realm of children's literature. His vibrant, humorous, and dynamic artwork not only captivated audiences in the latter half of the 19th century but also fundamentally reshaped the concept of the picture book, paving the way for its modern form. His legacy endures, most notably through the prestigious Caldecott Medal, an annual award recognizing the pinnacle of American picture book art. This exploration delves into the life, work, influences, and lasting impact of an artist whose lines danced with life and whose vision continues to inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings in Chester

Randolph Caldecott was born on March 22, 1846, in the historic city of Chester, Cheshire, England. He was the third child of John Caldecott, a respected local businessman and accountant, and Mary Dinah Brookes. Chester, with its Roman walls, medieval Rows, and picturesque half-timbered buildings, provided a rich visual tapestry for a young, observant mind. The surrounding Cheshire countryside, with its farms, hunts, and rural characters, would also deeply imprint itself on his artistic imagination.

Tragically, Caldecott's mother passed away when he was very young, an event that undoubtedly cast a shadow over his early years. His father later remarried. Despite this early loss, Randolph was described as a cheerful and active child, with a burgeoning passion for drawing and observing the world around him. He was particularly fond of animals, sketching them with an early-developed keen eye for their form and movement. He also enjoyed carving wooden figures of animals and people, a precursor to his later sculptural interests.

His formal education took place at The King's School in Chester (then known as King Henry VIII School). While he was a reasonably good student, his true passion lay outside the standard curriculum. He spent countless hours sketching in the margins of his books and filling notebooks with drawings of local scenes, market days, and the characters he encountered. This early, self-driven practice was crucial in honing his observational skills and his ability to capture the essence of a subject with a few deft strokes.

The Manchester Years: Banking and Budding Artistry

At the age of fifteen, in 1861, Caldecott's formal schooling concluded. Following a practical path, perhaps influenced by his father's profession, he left Chester to take up a position as a clerk at the Whitchurch & Ellesmere Bank in Whitchurch, Shropshire. This was a significant move for the young man, taking him away from his familiar surroundings. Despite the demands of his banking career, Caldecott's artistic pursuits did not wane; if anything, the new environment provided fresh subjects. He spent his leisure hours exploring the Shropshire countryside, often on horseback, sketching landscapes, rural life, fox hunts, and agricultural fairs.

It was during this period that Caldecott achieved his first taste of publication. In 1861, a drawing he made depicting a disastrous fire at the Queen Railway Hotel in Chester was published in the prestigious Illustrated London News. This was a remarkable achievement for a fifteen-year-old amateur and must have provided significant encouragement.

After six years in Whitchurch, Caldecott was transferred to the head office of the Manchester & Salford Bank in Manchester in 1867. Manchester, a bustling hub of the Industrial Revolution, offered a stark contrast to the rural tranquility of Whitchurch and Chester. It also provided greater opportunities for artistic development. He enrolled in evening classes at the Manchester School of Art (then Manchester Mechanics' Institution), where he received more formal instruction. He also joined various artistic societies, connecting with other aspiring and established artists.

During his time in Manchester, Caldecott began to contribute illustrations to local papers and periodicals. His talent for humorous and lively depictions of social scenes and characters started to gain recognition. He was also an avid theatre-goer, and the movement and expressions of actors on stage likely further informed his ability to convey narrative and emotion in his drawings. However, the life of a bank clerk, even with artistic pursuits on the side, was not his ultimate ambition. The pull towards a full-time career as an artist grew stronger.

A New Path in London: The Slade School and Early Success

By 1872, at the age of twenty-six, Randolph Caldecott made the pivotal decision to leave the security of his banking career and move to London to pursue art full-time. This was a bold step, but his growing portfolio and connections, including the encouragement of established artists like Thomas Armstrong (later Director for Art at the South Kensington Museum) and George du Maurier, a prominent Punch illustrator, gave him confidence.

Upon arriving in London, Caldecott sought to further refine his skills. He enrolled as a student at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, studying under Sir Edward Poynter, a classical painter. At the Slade, he would have been exposed to rigorous academic training, focusing on drawing from life and the antique. Alphonse Legros, another influential figure at the Slade, known for his etching and painting, also taught there during this period, emphasizing strong draughtsmanship. This formal training, combined with his innate talent and years of self-practice, helped to solidify his technique.

London's vibrant artistic and literary scene provided fertile ground for Caldecott. He quickly began to secure commissions. His work appeared in popular periodicals such as London Society, The Graphic, and the American publication Harper's Monthly Magazine. He also contributed to Punch, the leading satirical magazine, placing him in the company of renowned illustrators like John Tenniel (famous for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) and Charles Keene.

A significant early commission came from the writer Henry Blackburn, who asked Caldecott to illustrate his travel book, The Harz Mountains: A Tour in the Toy Country (1873). Caldecott himself traveled to Germany to make sketches for this project. The resulting illustrations were praised for their freshness and humor, further establishing his reputation. He also began to exhibit paintings in oil and watercolour at the Royal Academy and other galleries, demonstrating his versatility. He even took up sculpture, studying briefly with the French sculptor Aimé-Jules Dalou, who was then a refugee in London. Caldecott produced several accomplished small sculptures and bas-reliefs.

The Crucial Partnership with Edmund Evans

One of the most significant turning points in Caldecott's career came in the late 1870s when he was approached by Edmund Evans. Evans was a preeminent wood engraver and colour printer who had revolutionized children's book production. He had previously collaborated with Walter Crane on a successful series of "Toy Books," which were notable for their high-quality colour printing and artistic merit. When Crane moved on to other projects, Evans sought a new artist with a distinctive style.

Evans saw in Caldecott's work a unique blend of humor, dynamism, and observational skill that he believed would be perfect for children's books. In 1877, Evans proposed a collaboration: Caldecott would provide the illustrations for two books per year, to be published by George Routledge & Sons, and Evans would engrave and print them using his meticulous colour woodblock process. This partnership was to prove immensely fruitful.

The first two Caldecott "Picture Books," as they came to be known, were The House That Jack Built and The Diverting History of John Gilpin, both published for Christmas 1878. They were an immediate and resounding success. Caldecott's lively, action-filled drawings, perfectly complemented by Evans's sensitive colour printing, set a new standard for children's picture books. The books were typically priced at one shilling, making them accessible to a wide audience.

The collaboration with Evans was crucial. Evans's process involved creating separate woodblocks for each colour (typically black for the key lines, and then several blocks for flat colours – often buffs, blues, reds, and greens). Caldecott would provide a key drawing and often watercolour washes or notes to guide Evans's engravers and printers. The genius of their collaboration lay in the harmonious integration of line and colour, creating illustrations that were both graphically strong and aesthetically pleasing. The use of space, the flow of movement across pages, and the subtle interplay between text and image were hallmarks of their work.

Defining a Style: Movement, Humor, and the English Countryside

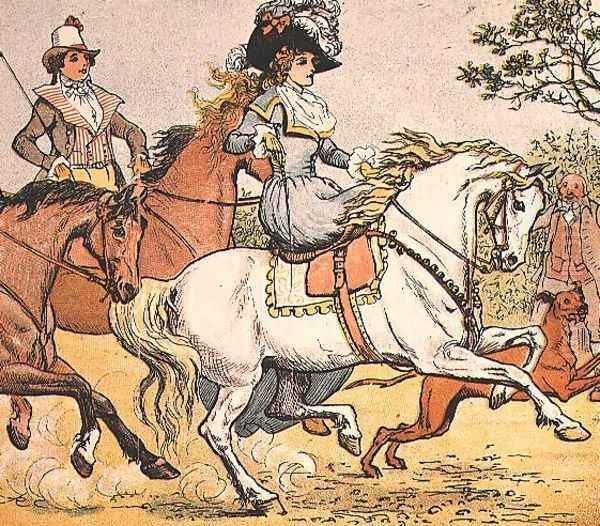

Randolph Caldecott's artistic style is instantly recognizable for its vitality, charm, and wit. He possessed an extraordinary ability to convey movement and energy with an economy of line. His figures, whether human or animal, are never static; they leap, run, ride, and tumble across the page with infectious enthusiasm. This sense of dynamism was a key differentiator from the more decorative or static styles of some of his contemporaries.

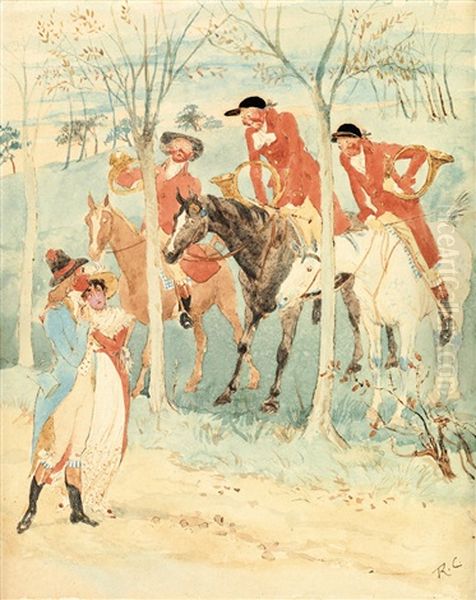

Humor was another defining characteristic. Caldecott's humor was gentle and observational, often found in the subtle expressions of his characters, the amusing predicaments they found themselves in, or the playful interactions between figures. He had a particular fondness for depicting dogs and horses, and his portrayals of these animals are full of character and understanding. His hunting scenes, a recurring theme, are not just about the chase but also about the camaraderie, the mishaps, and the sheer exuberance of the activity.

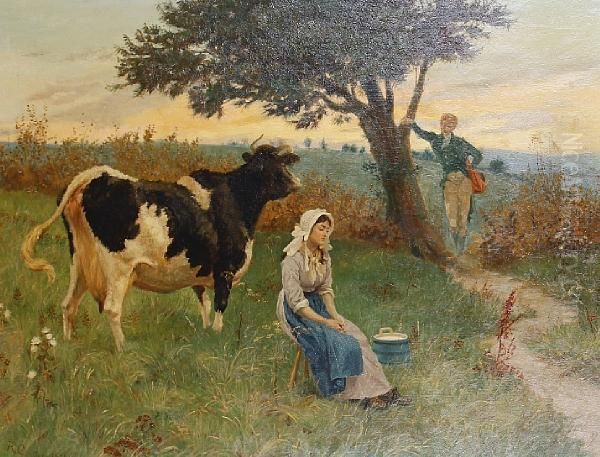

The English countryside formed the backdrop for much of Caldecott's most beloved work. He drew on his memories of Cheshire and Shropshire, and his observations from his travels around rural England. His scenes are populated with quintessential English characters: ruddy-faced squires, cheerful milkmaids, mischievous children, and sturdy farmers. He depicted a somewhat idealized, yet still recognizable, vision of pastoral England, one that resonated deeply with the Victorian public, many of whom were experiencing the rapid urbanization of the country.

Technically, Caldecott was a master of line. His penmanship was fluid and expressive, capable of suggesting form and texture with remarkable efficiency. He understood the importance of white space, using it effectively to create a sense of airiness and to focus the viewer's attention. While his colour, as printed by Evans, was often applied in flat tones, it was chosen with great care to enhance the mood and narrative of the illustrations. He often employed vignettes – small, unbordered drawings – alongside larger, more detailed scenes, a technique that added visual interest and allowed for parallel narratives or humorous asides. This "less is more" approach, particularly in his line work, was quite modern for its time and influenced generations of illustrators.

Masterpieces of the Nursery: Caldecott's Picture Books

Between 1878 and his death in 1886, Randolph Caldecott produced a series of sixteen picture books with Edmund Evans for George Routledge & Sons, typically two per year. These books cemented his fame and became nursery classics.

The Diverting History of John Gilpin (1878), based on William Cowper's humorous 18th-century poem, was an early triumph. Caldecott's illustrations perfectly capture the escalating chaos of Gilpin's unintended equestrian adventure. The sense of speed, the expressions of alarm and amusement on the faces of the onlookers, and the sheer panic of Gilpin himself are brilliantly rendered. Each page turn propels the narrative forward with cinematic energy.

The House That Jack Built (1878), a traditional nursery rhyme, was given new life through Caldecott's imaginative interpretation. He expanded on the simple cumulative tale, creating a visual narrative full of charming details and characterful animals. The dog, the cat, the rat, and the cow are all imbued with distinct personalities.

Other notable titles in the series include:

An Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog (1879) by Oliver Goldsmith, where Caldecott masterfully balances pathos and humor.

The Three Jovial Huntsmen (1880), a boisterous tale of well-meaning but comically inept hunters, showcasing Caldecott's love for equestrian scenes and rural characters.

Sing a Song for Sixpence (1880), where the "four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie" are depicted with delightful absurdity.

The Queen of Hearts (1881), a playful rendition of the rhyme about the stolen tarts.

Hey Diddle Diddle, and Baby Bunting (1882), where the fantastical elements of the nursery rhyme are brought to life with charm and whimsy.

A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go (1883), a perennial favorite, filled with expressive animal characters and a dramatic narrative arc.

In these books, Caldecott often extended the story beyond the confines of the text. His illustrations didn't just accompany the words; they expanded upon them, adding subplots, character development, and visual jokes. He understood that children read pictures as intently as they listen to words, and he provided a rich visual feast. This innovative approach, where pictures and text work in true partnership to tell a story, was a hallmark of his genius and a key contribution to the development of the modern picture book. Maurice Sendak, a towering figure in 20th-century children's literature, often cited Caldecott as a primary influence, particularly admiring his ability to create a seamless flow of action from page to page.

Beyond Picture Books: Other Illustrations and Artistic Pursuits

While Caldecott is best remembered for his children's picture books, his artistic output was diverse. He continued to illustrate for adult audiences throughout his career. He provided illustrations for Washington Irving's classic works Old Christmas (1876) and Bracebridge Hall (1877). These drawings, often depicting festive scenes, coaching inns, and English country life, were highly acclaimed and showcased his affinity for capturing the spirit of a bygone era. His style in these works was somewhat more detailed and refined than in his picture books, demonstrating his adaptability.

He also illustrated Juliana Horatia Ewing's Jackanapes (1884) and Lob Lie-by-the-Fire (1885), bringing a sensitive and empathetic touch to these popular children's stories. His contributions to magazines like The Graphic continued, and these often included social satire and observations of contemporary life.

His interest in sculpture, though a smaller part of his oeuvre, was genuine. He exhibited pieces like "A Horse Fair in Brittany" at the Royal Academy. This three-dimensional work informed his understanding of form and movement, which undoubtedly fed back into his two-dimensional illustrations.

Caldecott was also an avid traveler. His journeys to Brittany, Italy, and later to America provided him with fresh inspiration and subject matter. His sketchbooks from these travels are filled with lively observations of people, customs, and landscapes.

Caldecott and His Contemporaries: A Triumvirate of Talent

Randolph Caldecott, Walter Crane, and Kate Greenaway are often referred to as the "triumvirate" of late Victorian children's book illustrators. All three artists collaborated with Edmund Evans, and their work collectively elevated the status and quality of children's books during this "Golden Age" of illustration.

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was known for his more decorative and formal style, often influenced by Japanese prints and Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics. His designs were elegant and meticulously composed, with rich patterns and often allegorical content. While highly respected, Crane's work could sometimes feel more static and less overtly humorous than Caldecott's.

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901), born in the same year as Caldecott, created a distinctive world of quaintly dressed children in idyllic, old-fashioned settings. Her style was delicate, charming, and immensely popular, sparking a fashion trend for Greenaway-style children's clothing. Her vision was more sentimental and nostalgic, focusing on the innocence and grace of childhood, in contrast to Caldecott's more robust and action-oriented scenes.

While all three were immensely talented and successful, Caldecott's particular genius lay in his narrative power, his ability to convey character and emotion through gesture and expression, and his unparalleled depiction of movement. His work had a directness and an unpretentious charm that appealed to both children and adults. There was a friendly rivalry among them, but also mutual respect. It is said that Kate Greenaway was particularly inspired by Caldecott's success to pursue her own distinctive path in children's book illustration.

Other notable illustrators of the period included Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, though their major contributions came slightly later, building on the foundations laid by Caldecott and his immediate contemporaries. The influence of earlier artists like Thomas Bewick, with his masterful wood engravings of animals and rural life, and George Cruikshank, known for his vigorous and humorous caricatures, can also be seen as precursors to the rich illustrative traditions that Caldecott inherited and transformed.

Influences On and By Caldecott

Caldecott's art was not created in a vacuum. He absorbed influences from various sources. The English tradition of sporting art, with its focus on horses and hunting, was clearly an inspiration. The satirical and humorous drawings of artists like William Hogarth and Thomas Rowlandson, and later Punch illustrators like John Leech and Charles Keene, informed his comedic sense and his keen observation of social manners.

His time at the Slade School, with its emphasis on draughtsmanship, would have reinforced his natural talent for line. His travels provided a constant stream of new visual material. But perhaps his greatest influence was his own deep love for the English countryside and its way of life, and his innate ability to see the humor and humanity in everyday situations.

Conversely, Caldecott's influence on subsequent generations of illustrators has been profound. His emphasis on movement, his skillful use of line and space, and his creation of a true interplay between text and image set a new benchmark. Artists like Beatrix Potter, whose father Rupert Potter was an acquaintance of Caldecott and owned some of his original artwork, undoubtedly learned from his narrative techniques and his ability to imbue animal characters with personality. L. Leslie Brooke, another prominent early 20th-century illustrator, clearly followed in Caldecott's tradition of lively, humorous animal stories.

The very structure of the picture book, where the illustrations carry a significant part of the narrative load, owes much to Caldecott's innovations. He demonstrated that pictures could do more than just decorate a text; they could amplify it, counterpoint it, and even tell their own parallel stories.

Travels and Declining Health

Throughout his life, Randolph Caldecott suffered from delicate health. He had rheumatic fever as a child, which likely left him with a weakened heart. He also suffered from chronic gastritis. Despite these ailments, he maintained a remarkably productive career and a generally cheerful disposition.

In search of warmer climates to alleviate his health problems, Caldecott often spent winters abroad. He traveled to the Mediterranean, including Italy and the French Riviera. In 1879, he married Marian Brind, who accompanied him on his travels and was a supportive partner.

In the autumn of 1885, seeking a mild winter, Randolph and Marian Caldecott embarked on a journey to the United States. Their itinerary included a tour of the East Coast, with plans to spend the winter in Florida. Caldecott intended to sketch and gather material for a planned series of illustrations of American life.

The Final Journey and Untimely Death

The Caldecotts arrived in Florida in the late autumn of 1885. However, the winter that year proved to be unusually cold and damp, even in Florida. Caldecott's already fragile health deteriorated rapidly. He contracted acute gastritis, exacerbated by the cold weather and his underlying heart condition.

Randolph Caldecott passed away on February 12, 1886, in St. Augustine, Florida. He was just thirty-nine years old. His death at such a young age, at the height of his creative powers, was a great loss to the world of art and literature. He was buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in St. Augustine. A memorial tablet to him, designed by his friend, the sculptor Sir Alfred Gilbert (creator of the Eros statue in Piccadilly Circus), was later placed in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, and another in Chester Cathedral.

His wife, Marian, preserved his studio and many of his original drawings and sketchbooks. Much of this collection was later donated by his family, forming the core of the Caldecott holdings at the Worcester City Museum and Art Gallery, and other institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum also hold examples of his work.

The Enduring Legacy: The Caldecott Medal and Beyond

Though his career was tragically short, Randolph Caldecott's impact has been long-lasting. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of children's illustration and a key progenitor of the modern picture book. His ability to tell a story visually, to create memorable characters, and to infuse his work with energy and humor set him apart.

His most visible legacy is the Caldecott Medal. In 1937, Frederic G. Melcher, then editor of Publishers Weekly and a passionate advocate for children's literature (who had also initiated the Newbery Medal for children's literature in 1922), proposed the creation of an award to honor the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children published in the United States during the preceding year. This award was named in honor of Randolph Caldecott.

The Caldecott Medal is administered by the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), a division of the American Library Association (ALA). The first medal was awarded in 1938 to Dorothy P. Lathrop for Animals of the Bible. The medal itself features a design based on one of Caldecott's illustrations from The Diverting History of John Gilpin, showing John Gilpin on his runaway horse, surrounded by other characters from Caldecott's books. This design beautifully encapsulates the spirit of Caldecott's work – its dynamism, its narrative quality, and its connection to the joy of childhood reading.

The establishment of the Caldecott Medal was a landmark event. It recognized the illustrator as an artist of equal importance to the author in the creation of a picture book. It has significantly raised the profile of picture book art and has encouraged excellence and innovation in the field for over eighty years. Winning the Caldecott Medal is one ofthe highest honors an American children's book illustrator can receive.

Beyond the medal, Caldecott's influence is seen in the work of countless illustrators who have followed him. His emphasis on clear, expressive line work, his mastery of pacing and page design, and his ability to create a complete and engaging world within the pages of a book continue to be relevant. His picture books are still in print and continue to delight new generations of children, a testament to their timeless appeal.

Conclusion: The Unmistakable Imprint of a Master

Randolph Caldecott was more than just a talented illustrator; he was a visual storyteller of the first rank. He understood the unique power of the picture book to engage a child's imagination and to convey narrative with wit, warmth, and vivacity. His art, characterized by its flowing lines, its keen observation of human and animal nature, and its infectious good humor, breathed new life into traditional nursery rhymes and stories.

His partnership with Edmund Evans demonstrated the artistic possibilities of color printing in children's books, setting a standard for quality and aesthetic appeal. He, along with Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway, helped to usher in a golden age of children's illustration, transforming the humble "toy book" into a sophisticated art form.

Though his life was cut short, Randolph Caldecott left an indelible mark on the world. His picture books remain beloved classics, and the Caldecott Medal ensures that his name and his pioneering spirit continue to be associated with the very best in children's book illustration. He truly was, as Maurice Sendak called him, a "benchmark" and an "inventor of the picture book as we know it." His legacy is not just in the beautiful books he created, but in the joy and wonder they continue to bring to readers of all ages.