Thomas Bewick stands as a monumental figure in the history of British art and printmaking. Born in a humble cottage in Cherryburn, Northumberland, in August 1753, he rose to become the foremost wood engraver of his era, revolutionizing the medium and leaving an indelible mark on book illustration and the popular appreciation of the natural world. His meticulous craftsmanship, keen observational skills, and profound empathy for nature and rural life imbued his work with a timeless appeal that continues to captivate audiences today. This exploration delves into the life, work, artistic innovations, and enduring legacy of a man whose engravings brought the flora and fauna of Britain to vivid life for an eager public.

Early Life and Budding Talents

Thomas Bewick's early years were spent amidst the rustic beauty of the Tyne Valley, an environment that profoundly shaped his artistic sensibilities. His father, John Bewick, was a tenant farmer at Cherryburn, near Mickley, and also managed a small colliery. Young Thomas received a rudimentary education at the village school in Mickley, run by the Reverend Christopher Gregson. However, his formal schooling was less influential than the informal education he received from the natural world around him. He displayed an early and irrepressible passion for drawing, often using any available surface – from hearthstones with chalk to the margins of his schoolbooks – to sketch the animals and scenes he observed.

His father, a practical man, initially viewed his son's artistic inclinations with some skepticism, perhaps seeing little future in such pursuits. Despite this, Thomas's talent was undeniable. He was particularly drawn to depicting animals, a fascination that would become the hallmark of his career. The vibrant rural life, with its farms, wildlife, and local characters, provided an endless source of inspiration. He was not a formally trained artist in the academic sense; his skills were honed through direct observation and relentless practice. This self-taught foundation, rooted in empirical study rather than established artistic conventions, would later contribute to the freshness and authenticity of his work.

Apprenticeship and the Newcastle Scene

At the age of fourteen, in 1767, Thomas Bewick was apprenticed to Ralph Beilby, an engraver in Newcastle upon Tyne. Beilby's workshop handled a wide variety of engraving work, from decorating silverware and jewelry to producing billheads, trade cards, and illustrations for books, primarily using copperplate engraving. While Beilby himself was not a specialist in wood engraving, the workshop occasionally undertook such commissions. It was here that Bewick was introduced to the craft that he would come to master and redefine.

Initially, Bewick found much of the routine commercial work tedious. However, he applied himself diligently, learning the fundamentals of engraving. He showed a particular aptitude for wood engraving, a relief printing technique that had largely fallen out of favor for fine illustration, often relegated to cheaper, cruder publications. Copperplate engraving, an intaglio process, was then the preferred medium for high-quality book illustration. Bewick, however, saw untapped potential in wood. He began to experiment with tools and techniques, particularly using dense, end-grain boxwood and fine engraving tools typically associated with metalwork, like the burin. This allowed for much finer detail and tonal variation than was previously common in woodcuts, which were traditionally made on the plank side of softer woods.

During his apprenticeship, Bewick also began to gain recognition for his skill. In 1775, while still an apprentice, he received a premium from the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce for a wood engraving titled "The Huntsman and the Old Hound," intended as an illustration for Gay's Fables. This award was a significant early acknowledgment of his talent and likely bolstered his confidence in the potential of wood engraving.

Upon completing his seven-year apprenticeship in 1774, Bewick did not immediately settle. He spent a brief period working in London in 1776, where he found the city life uncongenial and the commercial art scene somewhat disillusioning. He worked for a time with the engraver Isaac Taylor, but his heart remained in Northumberland. He famously disliked the "dishonesty and conceit" he perceived in the capital and longed for the familiar landscapes and honest folk of his home county.

The Beilby and Bewick Partnership

In 1777, Thomas Bewick returned to Newcastle and entered into partnership with his former master, Ralph Beilby. The firm of Beilby & Bewick became a prominent engraving business in the North of England. Beilby, an educated man with literary interests, often handled the copperplate work and the textual elements of their joint publications, while Bewick increasingly focused on wood engraving and design. Their workshop trained a number of apprentices who would go on to become notable engravers themselves, including Bewick's own younger brother, John Bewick, and later figures like Luke Clennell and William Harvey.

The partnership was a fruitful one, undertaking a diverse range of commissions. They produced illustrations for children's books, such as A Pretty Book of Pictures for Little Masters and Misses, or, Tommy Trip's History of Beasts and Birds (for Thomas Saint), and various editions of fables. These early works allowed Bewick to refine his skills in depicting animals and to develop his characteristic style, which combined anatomical accuracy with a lively sense of character.

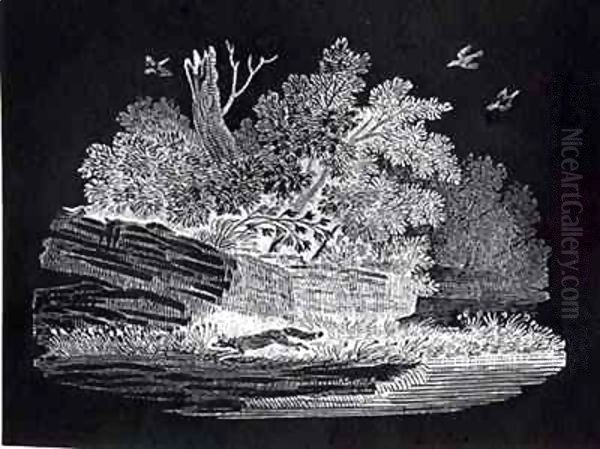

One of Bewick's significant technical contributions during this period was his popularization and refinement of the "white-line" technique in wood engraving. Unlike traditional woodcuts where the artist cuts away the wood around black lines, in white-line engraving, the artist incises lines into the block that will appear as white against a black or toned background when printed. This method, executed on the hard end-grain of boxwood, allowed for exceptionally fine detail, subtle gradations of tone, and a richness comparable to mezzotint on copper. Bewick was not the inventor of this technique, but he was its supreme master, demonstrating its full expressive potential. His tools, including various gravers and burins, were adapted from those used by metal engravers, allowing him to achieve unprecedented delicacy.

Masterpieces of Natural History: Quadrupeds and British Birds

The Beilby & Bewick partnership is best remembered for two landmark publications that cemented Thomas Bewick's reputation: A General History of Quadrupeds and A History of British Birds. These works were not merely illustrated books; they were comprehensive natural histories that combined scientific observation with artistic genius.

A General History of Quadrupeds

Published in 1790, A General History of Quadrupeds was an immediate success. The text was compiled by Ralph Beilby, drawing on existing natural histories by authors like Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Thomas Pennant, and Oliver Goldsmith. However, it was Bewick's vibrant and lifelike wood engravings that truly set the book apart. He depicted a wide array of animals, both domestic and exotic, with an accuracy and vitality rarely seen before. Bewick often drew from life when possible, sketching animals in menageries or on farms. For more exotic creatures, he relied on stuffed specimens or existing illustrations, but always imbued them with his characteristic sense of life and personality.

The Quadrupeds was praised for its detailed and sympathetic portrayals. Each animal was typically shown in a characteristic pose and often within a miniature landscape setting that hinted at its natural habitat. The book also featured numerous small "tail-pieces" or vignettes at the end of sections – a Bewick trademark. These tiny, often humorous or moralistic scenes of rural life, landscapes, and everyday incidents showcased Bewick's keen eye for social observation and his deep affection for the Northumbrian countryside. These vignettes, rich in narrative and detail despite their diminutive size, became as beloved as the main illustrations. The success of Quadrupeds went through many editions, demonstrating the public's appetite for accessible and beautifully illustrated natural history.

A History of British Birds

Following the triumph of Quadrupeds, Bewick embarked on an even more ambitious project: A History of British Birds. This was published in two volumes: Land Birds in 1797 and Water Birds in 1804. For the first volume, Beilby again provided much of the text, though Bewick, an avid ornithologist himself, contributed significantly to the descriptions, drawing on his own extensive observations. By the time the second volume was in preparation, disagreements over authorship and profits led to the dissolution of the Beilby & Bewick partnership in 1797. Bewick took over the project, and the text for Water Birds was largely written by the Reverend Henry Cotes, though edited and supplemented by Bewick.

The engravings in British Birds are widely considered the pinnacle of Bewick's art. His intimate knowledge of birds, their habitats, and their behaviors is evident in every image. He depicted each species with remarkable accuracy, capturing not only their plumage and anatomy but also their characteristic postures and expressions. The birds are often set against meticulously rendered backgrounds that evoke their natural environments – a windswept moor, a reedy marsh, a craggy cliff face. The textures of feathers, bark, stone, and water are rendered with astonishing skill.

The tail-pieces in British Birds are even more numerous and varied than in Quadrupeds. They offer a captivating panorama of rural life, folklore, social commentary, and personal reflections. Some are humorous, others poignant; some depict scenes of hardship, while others celebrate the simple pleasures of country living. These vignettes reveal Bewick's compassionate nature, his wry sense of humor, and his deep connection to the landscape and people of his native Northumberland. They are miniature masterpieces in their own right, demonstrating his ability to convey complex narratives and emotions within a tiny compass. The influence of artists like William Hogarth, known for his satirical and moralizing print series, can be discerned in the narrative and social commentary of some of Bewick's tail-pieces.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Further Works

Thomas Bewick's artistic style was characterized by its realism, meticulous detail, and profound empathy. He possessed an extraordinary ability to observe and record the natural world with both scientific precision and artistic sensitivity. His engravings are not mere copies of nature but interpretations that convey the essence and spirit of his subjects. He was a master of light and shadow, using the white-line technique to create a rich range of tones and textures.

His commitment to working from life whenever possible was crucial. He would often keep specimens, or study them closely, ensuring anatomical accuracy. This dedication to direct observation set him apart from many contemporary illustrators who relied more heavily on stylized conventions or copying earlier works. His deep understanding of animal anatomy, likely influenced by the work of artists like George Stubbs who made extensive studies of animal physiology, lent a powerful sense of realism to his depictions.

After the completion of British Birds, Bewick continued to work prolifically. He produced illustrations for numerous other books, including an edition of The Fables of Aesop (published in 1818). This project had been a lifelong ambition, and he poured much effort into its illustrations, which again featured his signature tail-pieces. While some critics felt the Fables did not quite reach the heights of British Birds, it remains a significant work, showcasing his mature style and his enduring interest in moral and didactic themes.

Beyond book illustration, Bewick's workshop undertook a wide range of commercial engraving work. This included producing bookplates, billheads, advertisements, and even designs for banknotes for provincial banks, where the fine detail of his engraving was intended to deter forgery. His influence extended to his apprentices, many of whom became accomplished engravers. His son, Robert Elliot Bewick, became his partner in later years, and the workshop continued under his name. Other notable pupils like Luke Clennell and William Harvey carried Bewick's techniques and aesthetic into the 19th century, influencing the next generation of illustrators and engravers. The quality of printing was also important to Bewick, and he often worked with skilled printers like William Bulmer, whose Bensley typefaces complemented Bewick's clear and detailed engravings.

Personal Life, Character, and Connection to Northumberland

Thomas Bewick married Isabella Elliot in 1786. She was the daughter of a Hexham farmer and a childhood friend. Their marriage was a happy one, and they had four children: Jane, Robert, Isabella, and Elizabeth. His family life was centered in Newcastle, though he maintained a deep connection to his birthplace, Cherryburn, which he eventually purchased.

Bewick was a man of strong character and firm principles. He was known for his integrity, his independent spirit, and his somewhat radical political views for the time, sympathizing with the ideals of the American and French Revolutions, though he abhorred violence. He was a keen reader, enjoying the works of authors like Walter Scott and William Cobbett. His writings, particularly his posthumously published Memoir (edited by his daughter Jane and published in 1862), reveal a thoughtful, observant, and deeply moral man. The Memoir provides invaluable insights into his life, his working methods, his views on art and nature, and the social conditions of his time.

His love for Northumberland was profound and unwavering. The landscapes, wildlife, and people of his native county were a constant source of inspiration. He was an avid walker and fisherman, spending much of his leisure time exploring the countryside. This intimate connection with nature infused his work with an authenticity and passion that resonated deeply with his audience. He was, in many ways, a quintessential Northumbrian: practical, down-to-earth, and possessed of a dry wit.

The death of his parents and sister in 1785 (not 1875 as sometimes misreported) was a period of significant personal loss, occurring just before his marriage and the peak of his artistic output. These experiences may have deepened his reflective and sometimes melancholic observations on life and mortality, often subtly expressed in his tail-pieces.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Thomas Bewick remained active as an engraver and artist well into his later years. He continued to work on new projects and to revise and improve earlier ones. One of his final major undertakings was a series of large wood engravings of animals, intended for a projected History of British Fishes, which remained unfinished at his death. One of these, "The Chillingham Bull" (1789), a depiction of a wild bull from the ancient herd at Chillingham Castle, is among his most celebrated individual prints, showcasing his mastery of texture and dramatic composition.

Thomas Bewick died on November 8, 1828, at his home in Gateshead, across the River Tyne from Newcastle. He was buried in Ovingham churchyard, close to his beloved Cherryburn. His death was mourned by many, and his reputation as one of Britain's greatest artists was already firmly established.

Bewick's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. He revolutionized the art of wood engraving, transforming it from a relatively crude medium into a sophisticated and expressive art form. His technical innovations and artistic mastery set a new standard for book illustration. His work directly influenced generations of illustrators and printmakers, including prominent figures of the 19th-century illustration revival like the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who admired his meticulous detail and truth to nature. William Morris, a key figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, also revered Bewick and sought to emulate the quality of his integrated text and image in the books produced by the Kelmscott Press.

His natural history publications played a significant role in popularizing the study of zoology and ornithology. They made the natural world accessible and engaging for a wide audience, fostering a greater appreciation for Britain's native wildlife. His influence can be seen in the work of later naturalists and illustrators, such as John James Audubon, though Audubon worked on a vastly different scale and primarily with copperplate engraving and hand-coloring. Bewick's commitment to observation was akin to that of naturalists like Gilbert White, whose The Natural History of Selborne (1789) shared a similar spirit of close, affectionate study of local fauna.

Bewick's work also provides a valuable historical record of rural life in late 18th and early 19th-century Britain. His tail-pieces, in particular, offer a rich tapestry of social customs, agricultural practices, and everyday scenes, capturing a world that was rapidly changing with the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

Exhibitions and Continued Appreciation

The appreciation for Thomas Bewick's work has never truly waned. His books have remained in print or have been frequently reissued, and his engravings are prized by collectors. An important early posthumous recognition came with the exhibition of his watercolors and wood engravings by the Fine Art Society in London in 1880, which helped to solidify his reputation not only as a master engraver but also as a skilled watercolorist, as many of his preparatory drawings for the engravings were executed in this medium.

His birthplace, Cherryburn, is now a museum managed by the National Trust, preserving his legacy and offering visitors a glimpse into his early life and influences. Numerous exhibitions have been dedicated to his work over the years, both in the UK and internationally. For instance, the "Bewick and Back" project in 2016, organized by the Sunderland Cultural Partnership, highlighted his enduring connection to the region through a series of commemorative walks and events. His work continues to be studied by art historians, naturalists, and bibliophiles, and his influence is acknowledged in fields ranging from printmaking to scientific illustration and children's literature. The mathematician Charles Hutton, who collaborated with Bewick on some early projects, would have appreciated the precision Bewick brought to his craft.

Conclusion: An Artist of Nature and Truth

Thomas Bewick was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was an artist of profound vision and integrity. His meticulous wood engravings, born from a deep love and understanding of the natural world, set a new benchmark for illustration and brought the beauty of British wildlife to a wider public than ever before. His technical innovations revitalized wood engraving, establishing it as a respected artistic medium. Through his masterpieces, A General History of Quadrupeds and A History of British Birds, and the charming, insightful tail-pieces that adorned them, Bewick created an enduring legacy. He captured not only the forms of animals but also their spirit, and in doing so, he captured the spirit of his age and the timeless beauty of the Northumbrian landscape that he called home. His work remains a testament to the power of careful observation, artistic skill, and a deep connection to the natural world, securing his place as one of Britain's most beloved and influential artists.