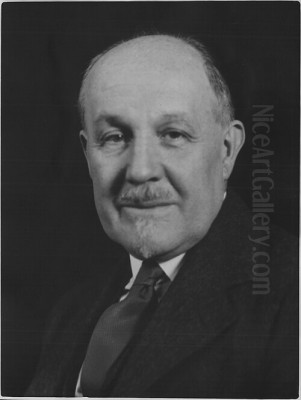

Ernest Lawson stands as a significant yet often subtly appreciated figure in the landscape of American art history. A Canadian-American painter whose career flourished primarily in the bustling artistic environment of New York City at the turn of the 20th century, Lawson carved a unique niche for himself. His work masterfully navigated the currents between the fading light of Impressionism and the burgeoning grittiness of American Realism, resulting in a style that was both deeply personal and reflective of the era's transitions. As a key member of the influential group known as "The Eight," Lawson contributed a distinct voice, focusing on the poetic potential of landscapes, even those touched by urban expansion, rather than the purely social commentary favored by some of his contemporaries. His life and art offer a compelling study of an artist grappling with tradition, innovation, and the complexities of modern life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Ernest Lawson was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on March 22, 1873. His early years were marked by movement; the family relocated to Kansas City, Missouri, which would become the site of his initial artistic explorations. It was at the Kansas City Art Institute where Lawson first received formal training. Significantly, one of his instructors there was Ella Holman, an artist who would not only guide his early development but would later become his wife, intertwining his personal and artistic paths from the outset.

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced instruction, Lawson made the pivotal move to New York City in 1888. This relocation placed him at the heart of the American art world and led him to enroll at the prestigious Art Students League. This institution was a crucible for emerging talent, and Lawson found himself under the tutelage of two prominent figures of American Impressionism: John Henry Twachtman and J. Alden Weir. Their influence, particularly their emphasis on capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere, profoundly shaped Lawson's burgeoning style.

Further immersing himself in the Impressionist ethos, Lawson participated in the summer art colony at Cos Cob, Connecticut. This colony, frequented by Twachtman, Weir, and other artists exploring Impressionist techniques, provided an environment steeped in plein air painting and the direct observation of nature. The lessons learned here, focusing on landscape, seasonal change, and the effects of light, would form the bedrock of Lawson's artistic practice for the rest of his career. His time studying with Twachtman, whom he deeply respected, was particularly formative, instilling in him the techniques of broken brushwork and a sensitivity to tonal harmonies.

Parisian Interlude and Impressionist Influences

Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Lawson recognized the importance of experiencing European art firsthand, particularly the innovations emanating from France. In 1893, he embarked on a journey to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. There, he studied under figures such as Jean-Paul Laurens, absorbing the academic rigor while simultaneously being exposed to the more radical currents flowing through the Parisian art scene. He also spent a brief period studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Saint-Étienne.

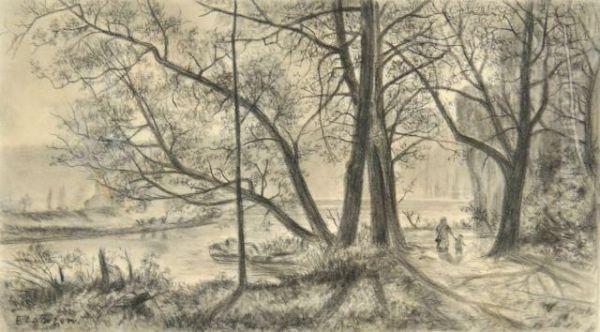

Crucially, his time in France brought him into contact with the work and, significantly, the person of Alfred Sisley. Sisley, one of the core figures of French Impressionism, known for his delicate and light-filled landscapes, became a key influence. Lawson reportedly met Sisley and spent time painting outdoors (en plein air) in the south of France, further solidifying his commitment to Impressionist principles. The experience of painting directly from nature, capturing fleeting moments of light and color under the French sky, and engaging with artists like Sisley, deepened his understanding and refined his approach. He also absorbed the atmospheric qualities found in the works of earlier landscape masters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, whose poetic sensibility resonated with Lawson's own inclinations.

This period abroad was not merely about technical refinement; it was about immersing himself in the Impressionist milieu. He saw firsthand how artists like Sisley translated the visual world into canvases shimmering with light and color. This experience undoubtedly emboldened Lawson to pursue his own landscape-focused path, armed with the techniques and aesthetic sensibilities honed through direct engagement with French Impressionism.

Return to America and Developing a Unique Vision

Ernest Lawson returned to the United States in 1896, bringing back the invaluable experiences and influences gained during his time in France. He settled primarily in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, New York City. This location proved artistically fertile, providing him with ready access to the subjects that would dominate his oeuvre: the landscapes of the Hudson River, the Harlem River, and the semi-urban fringes where the city met the countryside.

Back on American soil, Lawson began to synthesize his training and influences into a style distinctly his own. While clearly rooted in Impressionism, particularly the work of Twachtman, Weir, and Sisley, his approach evolved. He developed a characteristic technique involving thick applications of paint, often using a palette knife or even his thumb, creating a heavily textured surface. This impasto technique, combined with his vibrant and nuanced use of color, led critics to describe his canvases as having a "crushed jewels" effect – a surface that sparkled with encrusted pigment, capturing light in a tangible, almost sculptural way.

His focus remained primarily on landscape, but his perspective often differed from the more idyllic scenes favored by earlier American landscape painters or the purely atmospheric concerns of some Impressionists. Lawson was drawn to the transitional spaces, the views across the rivers showing bridges, distant buildings, or even the less picturesque elements of the urban edge. He found beauty in the everyday, rendering scenes of winter snow clinging to riverbanks, the budding trees of spring along the Palisades, or the shimmering reflections on the water, all imbued with a sense of place and a specific atmospheric mood. This unique blend of Impressionist technique and a focus on the specific character of the American landscape, particularly around New York, marked his mature style.

The Eight and the Ashcan School Context

Ernest Lawson's career became inextricably linked with one of the most significant movements in early 20th-century American art through his membership in "The Eight." This informal group, which came together for a landmark exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City in 1908, represented a rebellion against the conservative exhibition policies and aesthetic standards of the powerful National Academy of Design. Led ideologically by the charismatic painter and teacher Robert Henri, the group championed artistic freedom and the depiction of modern American life.

The members of "The Eight" were diverse in their styles: Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn were primarily urban realists, often depicting the gritty, everyday life of the city, earning them the later moniker of the "Ashcan School." Arthur B. Davies pursued a more lyrical, symbolic style, while Maurice Prendergast developed a unique, mosaic-like Post-Impressionist technique. Lawson stood apart as the group's dedicated landscape painter. His inclusion highlighted the group's broad opposition to academic constraints rather than adherence to a single stylistic dogma.

Lawson shared his fellow members' desire for independent exhibition venues and a more inclusive art world. He had become friends with William Glackens, who likely introduced him to Henri and the others. While his subject matter differed – focusing on the atmospheric beauty of the landscape rather than bustling street scenes or immigrant life – his commitment to personal vision and modern subjects aligned him with the group's progressive spirit. His landscapes, often depicting the less conventionally beautiful areas of Upper Manhattan or the industrial presence along the rivers, contained an element of realism that connected him to the Ashcan sensibility, even if his painterly technique remained rooted in Impressionism.

The 1908 exhibition was a succès de scandale, generating significant publicity and challenging the established art hierarchy. Lawson's participation solidified his reputation as a forward-thinking artist. He also exhibited works in the even more revolutionary Armory Show of 1913, which introduced European avant-garde art (like Cubism and Fauvism) to a shocked American audience. While Lawson's own work remained relatively consistent in style, his association with these landmark exhibitions placed him firmly within the narrative of American modernism's emergence. However, the exhibition system of "The Eight" did draw some criticism, with even Glackens reportedly finding the fee-based, approval-required structure somewhat objectionable, though Lawson himself seemed to view it as a step forward.

Lawson's Distinctive Style and Subject Matter

Ernest Lawson's artistic signature lies in his unique synthesis of Impressionist light and color with a tangible, almost physical paint application. His canvases are immediately recognizable for their thick, textured surfaces. He built up layers of pigment, often applying paint directly from the tube or manipulating it with a palette knife, creating a rich impasto. This technique moved beyond the typical broken brushwork of French Impressionism, giving his surfaces a dense, encrusted quality that captured and reflected light in a distinct way – the source of the "crushed jewels" comparison.

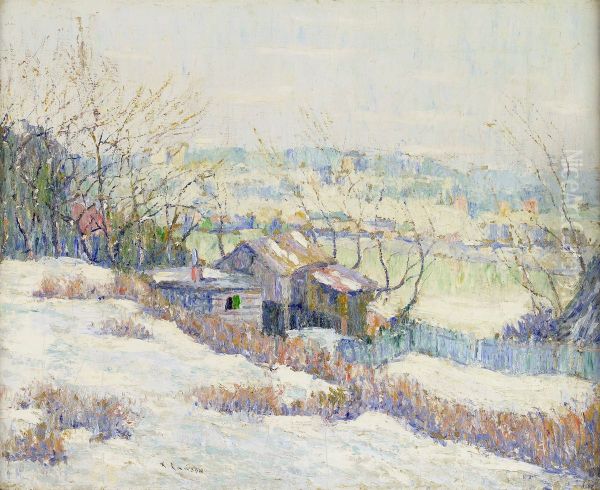

His palette was often high-keyed and vibrant, yet capable of great subtlety in capturing specific atmospheric conditions and times of day. He excelled at depicting the crisp light of winter, rendering snow with blues, violets, and pinks, and capturing the stark beauty of bare trees against a cold sky. His depictions of spring thaw or the hazy light of summer demonstrate a keen sensitivity to seasonal change. Works like Winter, Spuyten Duyvil exemplify his mastery of the winter landscape, finding beauty in the stark, snow-covered terrain at the confluence of the Harlem and Hudson Rivers.

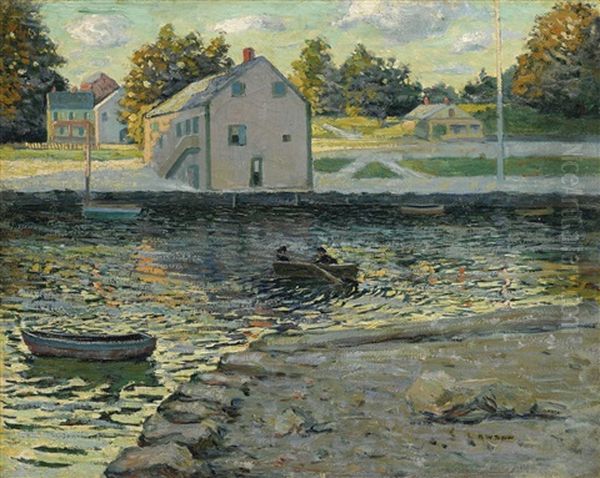

While influenced by Sisley and Twachtman, Lawson's landscapes possess a specific sense of American place. His recurring subjects were the environs of his Washington Heights home: the Palisades across the Hudson, the winding course of the Harlem River, High Bridge, and the surrounding hills and sparse settlements. Unlike the Impressionists who often sought purely pastoral scenes, Lawson frequently included elements of human infrastructure – bridges, boats, distant buildings, even shanties – integrating them into the landscape composition. Upper Harlem River and Boathouse, Winter, Harlem River showcase this focus on the specific topography and atmosphere of his chosen locale.

His work occupies a space between pure Impressionism and the burgeoning Realism of the Ashcan School. While he employed Impressionist techniques to capture light and atmosphere, his commitment to specific locations and his willingness to depict less idealized, sometimes semi-industrial landscapes, lent his work a grounded quality. He wasn't documenting social conditions like Sloan or Luks, but he wasn't ignoring the realities of the developing urban edge either. He found a poetic lyricism in these transitional spaces, a quality perhaps best seen in works like Green and Gold, where light transforms an ordinary scene into something evocative.

Recognition and Challenges

Throughout his career, Ernest Lawson achieved a considerable degree of recognition, even if he never reached the towering fame of some contemporaries. His unique style garnered positive attention from critics and collectors early on. He received prestigious awards, including a silver medal at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904 and the First Hallgarten Prize from the National Academy of Design in 1908 (despite his association with the rebellious "Eight"). A significant honor was winning the W. A. Clark Prize and Corcoran Gold Medal at the Corcoran Gallery of Art Biennial in Washington D.C. in 1916 for his painting Boat House, Winter, Harlem River.

His work attracted discerning collectors who appreciated his unique blend of Impressionism and realism. Figures like John Quinn, a major patron of modern art, and Dr. Albert C. Barnes, founder of the Barnes Foundation, acquired his paintings. This patronage indicates that Lawson was seen as a significant modern American painter by some of the most astute collectors of the era. His participation in the Armory Show also brought his work to a wider, albeit sometimes perplexed, audience.

Despite these successes, Lawson's life was marked by persistent challenges. Financial difficulties were a recurring theme. He often struggled to sell his work consistently, particularly as artistic tastes began to shift towards more radical European styles like Cubism and Fauvism, which were showcased at the Armory Show. Lawson's style, while modern in its context, did not evolve dramatically to embrace these newer, more abstract modes of expression. This adherence to his established vision, while artistically consistent, may have contributed to a decline in market appeal later in his career.

To supplement his income, Lawson occasionally took on teaching positions, including stints in Kansas City and at the Broadmoor Art Academy in Colorado Springs. Personal struggles also cast a shadow over his life. He battled alcoholism, which reportedly strained relationships with friends and family. Periods of depression further compounded his difficulties, creating a picture of an artist who, despite achieving professional recognition, faced significant personal and financial adversity. His friend, the writer Somerset Maugham, whom he met through William Glackens, even used Lawson as the inspiration for the character Frederick Lawson in his novel Of Human Bondage, capturing aspects of the struggling artist's life in Paris.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later career, Lawson continued to paint, seeking new landscapes and perhaps respite from his personal troubles. He spent a year in Spain around 1916, a period sometimes described as one of relative happiness, where he captured the distinct light and architecture of the region. He also traveled to Florida, finding new subject matter in the tropical landscapes, quite different from his signature New York scenes. His Florida paintings often feature brighter colors and depict the lush vegetation and waterways of the area.

However, his health continued to decline, and the grip of depression and alcoholism reportedly tightened. His artistic output may have become less consistent, and he faced increasing isolation from the mainstream art world, which was rapidly embracing newer forms of modernism championed by figures like Alfred Stieglitz and the artists in his circle, or the hard-edged styles of the Precisionists. Lawson remained committed to his own form of landscape painting, rooted in Impressionist observation but infused with his unique textural approach.

Ernest Lawson's life came to a tragic end on December 18, 1939. He was found drowned on Miami Beach, Florida. While the official cause was drowning, the circumstances, combined with his known history of depression and health problems, have led many to believe his death may have been a suicide. He was 66 years old.

His legacy is that of a bridge figure in American art. He connected the lyrical beauty of American Impressionism, learned from masters like Twachtman and Weir, with the emerging focus on contemporary American life championed by "The Eight." He was a landscape painter of immense sensitivity, capable of finding poetry in the overlooked corners of the urban fringe and capturing the distinct moods of the American seasons. While perhaps overshadowed by the more radical innovators who followed, Lawson's distinctive "crushed jewels" technique and his evocative depictions of the Hudson and Harlem River valleys secure his place as a unique and important voice in early 20th-century American painting. His work continues to be admired for its painterly richness and its quiet emotional depth.

Collections and Market Presence

Ernest Lawson's paintings are held in the collections of numerous major American and Canadian art museums, testament to his enduring significance. The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in his birthplace of Halifax holds works, including the early Regatta Day (1894), and has organized exhibitions celebrating his connection to the region. In the United States, his works can be found in institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art (whose collection is now largely integrated with the National Gallery of Art) notably acquired his award-winning Boathouse, Winter, Harlem River, 1916. The Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, holds several examples of his Harlem River scenes, including Upper Harlem River, 1915 and Path Along the River's Edge, 1905. The Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, includes An Old Saw Mill, 1915-1920 in its collection. Works like Young Trees were exhibited at venues like the Grand Central Art Galleries during his lifetime.

Lawson's paintings continue to appear on the art market, fetching respectable prices at auction, although generally not reaching the highest echelons occupied by some of his French Impressionist predecessors or later American modernists. Records indicate sales like a 1939 painting titled Connecticut River Boat reaching 0,000. Auction houses like Christie's regularly handle his work, assessing condition and provenance. While perhaps not as widely known to the general public as some other members of "The Eight" like Henri or Sloan, Lawson remains a sought-after artist for collectors specializing in American Impressionism and early 20th-century American art, valued for his unique style and evocative depictions of the American landscape.