The turn of the twentieth century was a period of breathtaking technological advancement and artistic innovation. Amidst the vibrant cultural landscape of Paris, one artist, Ernest Montaut, carved a unique niche for himself, becoming synonymous with the exhilarating nascent worlds of motorsport and aviation. His dynamic prints, pulsating with energy and a novel sense of velocity, not only chronicled the birth of these new machines but also defined a visual language for speed that would resonate for generations.

Early Life and Artistic Emergence

Ernest Montaut is widely believed to have been born in Paris in 1879, although some sources suggest the year 1878. Regardless of the precise year, his formative years coincided with the Belle Époque, a period of optimism, artistic flourishing, and a burgeoning fascination with science and engineering in France. Little is documented about his formal artistic training, but his prodigious talent for illustration and his keen eye for the mechanical marvels of his time quickly became apparent.

Montaut's career was tragically short; he passed away in 1909, at the young age of 30 or 31, reportedly due to acute appendicitis. Despite this brief span, his output was prolific and his impact significant, leaving behind a legacy of iconic images that continue to captivate collectors and enthusiasts of early automotive and aviation history.

The Roar of Engines: Montaut's Muse

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the thrilling, and often perilous, advent of the automobile and the airplane. These were not merely new modes of transport; they represented a paradigm shift, a conquest of distance and gravity that captured the public imagination. Races, rallies, and daring aerial feats became spectacles, drawing huge crowds and embodying the spirit of adventure and progress.

It was this electrifying atmosphere that Ernest Montaut so brilliantly captured. From the mid-1890s, he began producing a series of prints focused on these themes. His subjects were the heroes and the machines of this new age: intrepid drivers wrestling with primitive steering wheels, pioneering aviators navigating the skies in fragile contraptions, and the powerful, often temperamental, engines that propelled them. His works were not static portraits but vivid narratives of action, drama, and the relentless pursuit of speed.

These prints found a ready audience in Paris, a city at the forefront of both artistic and technological innovation. They were displayed and sold in fashionable shops along the Rue de l'Opéra and the Rue de la Paix, as well as in respected art galleries, appealing to a public eager for images that reflected the dynamism of modern life.

Pioneering a Visual Language for Speed

One of Ernest Montaut's most significant contributions to art and illustration was his innovative method for depicting motion and velocity. He is credited with inventing or, at the very least, popularizing the use of "speed lines" – streaks and blurs that trail behind a moving object, conveying a powerful sense of its passage through space. This technique, often combined with a dramatic, low-angle perspective and a slight distortion or elongation of the vehicle itself, created an almost palpable sensation of speed.

This was a departure from more traditional, static representations. Montaut understood that speed was not just about the machine, but about the experience and the visual impact of rapid movement. His lines were not merely descriptive; they were expressive, imbuing his scenes with an almost frantic energy. This technique was so effective that it was adopted by countless illustrators and cartoonists in the decades that followed and remains a staple in visual storytelling, particularly in comic books and animation, to this day.

Beyond speed lines, Montaut employed other clever visual devices. He often used foreshortening and exaggerated perspective to enhance the drama, making the vehicles appear to burst out of the frame towards the viewer. Dust clouds, flying debris, and the strained expressions of drivers and pilots further amplified the sense of intense action.

The Pochoir Process: Craftsmanship and Color

Montaut's prints were typically produced using the pochoir technique, a sophisticated and labor-intensive stencil-based printing process. First, a key-line image, usually a lithograph, would be printed to provide the basic outlines of the composition. Then, a series of stencils, meticulously cut by hand (one for each color), would be used to apply vibrant watercolors or gouache.

This manual application of color meant that each print, while part of an edition, possessed subtle variations, making it a unique work of art. The colors in Montaut's prints are often bright and dynamic, contributing significantly to their lively and exciting character. The pochoir process allowed for rich, opaque colors that could not be easily achieved with other contemporary printing methods. This dedication to craftsmanship set his work apart and contributed to its desirability. He often oversaw a studio of artists who would assist in the hand-coloring process, ensuring a consistent quality while allowing for the production of a reasonable number of prints.

Key Themes and Subjects in Montaut's Oeuvre

While best known for automobiles and airplanes, Montaut's fascination with speed and modern machinery extended to a variety of subjects.

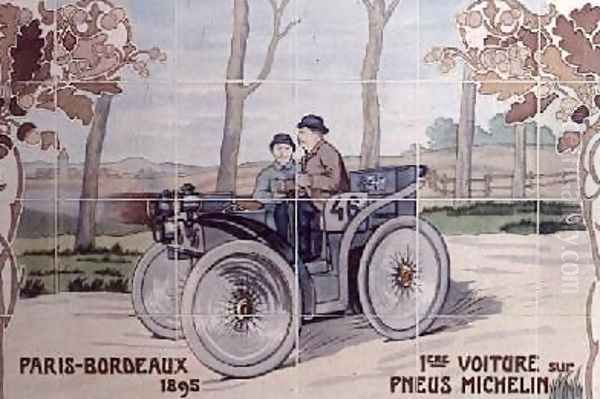

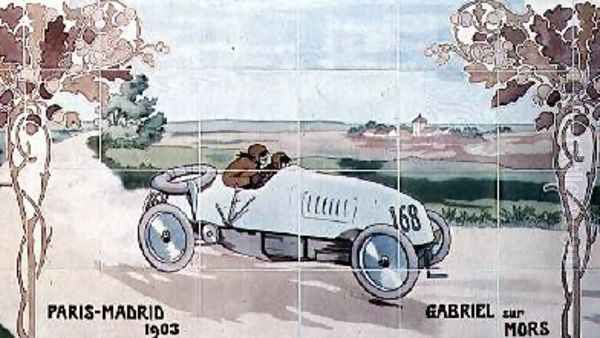

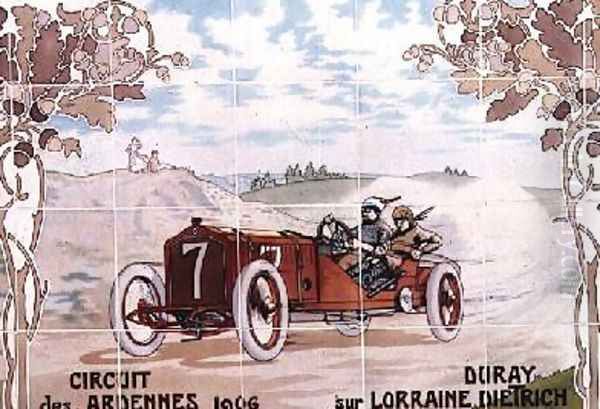

Automotive Art: This was arguably his most famous domain. He depicted legendary early motor races such as the Gordon Bennett Cup, the Paris-Rouen trial (often considered the first motor race), and grueling city-to-city rallies like the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris. His prints often featured specific makes of cars, implicitly promoting brands like Panhard, Peugeot, Renault, Mercedes, and Fiat. The drivers, often contemporary heroes like Camille Jenatzy or Vincenzo Lancia, were portrayed with a sense of daring and determination. Works like "Le Raid Mortel (Paris-Madrid 1903)" captured the danger and drama inherent in early motorsport. Another example, "En Course, la Voiture De Dietrich conduite par Gabriel sur la route de Paris-Madrid", showcases his typical dynamic style.

Aviation Art: As aviation moved from experimental fancy to fledgling reality, Montaut was there to document its milestones. He created images of early airships (dirigibles) and the pioneering flights of fixed-wing aircraft. His poster for the "Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne" held at Reims in 1909 is an iconic piece, capturing the excitement of one of the world's first major airshows. He also depicted Louis Blériot's historic 1909 flight across the English Channel, a feat that electrified the world. These prints often emphasized the fragility of the early aircraft against the vastness of the sky, highlighting the bravery of the aviators.

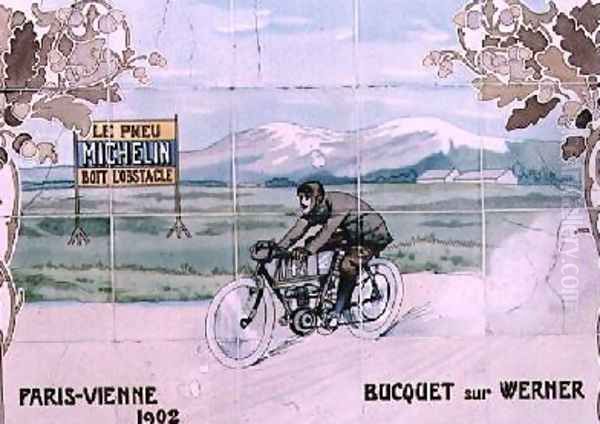

Motorcycles and Other Vehicles: Montaut also applied his distinctive style to the emerging world of motorcycle racing, capturing the lean and speed of these two-wheeled machines. Powerboat racing, another new and exciting sport, also featured in his portfolio, with sleek hulls cutting through the water, trailing dramatic wakes. Even bicycles, which had paved the way for individual mechanized transport, occasionally appeared in his work, often depicted in racing contexts.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Montaut's Portfolio

While many of his individual prints are highly sought after, some stand out as particularly representative of his style and subject matter:

"Paris-Bordeaux-Paris, 1895": An early example capturing the spirit of pioneering long-distance races.

"Tour de France Automobile, 1899": Illustrating the endurance and adventure of early multi-stage automotive events.

"La Coupe Gordon Bennett": A recurring theme, as this was one of the most prestigious international races of the era. Specific years, like 1903 or 1904, would feature prominently.

"Première Traversée de la Manche en Aéroplane par Blériot, 25 Juillet 1909": A tribute to Blériot's groundbreaking achievement.

"Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne, Reims, 1909": The famous poster that became an emblem of early aviation enthusiasm.

Prints featuring specific car brands in action, such as a speeding Brasier or a powerful Fiat, often with dramatic titles like "Dans la Fournaise" (In the Furnace) or "A Toute Vitesse" (At Full Speed).

These titles, often included directly on the print, added to the narrative and excitement of the images.

The Artistic Partnership: Ernest and Marguerite "Gamy" Montaut

Ernest Montaut did not work in isolation. His wife, Marguerite Montaut (née Gamat), was also an artist and played a crucial role in their artistic production. After Ernest's untimely death, Marguerite continued to produce prints in a similar style, often signing them "Gamy" (a contraction of her maiden and married names, Gamat-Montaut) or sometimes "M. Montaut."

It is widely believed that Marguerite was heavily involved in the coloring process of Ernest's prints even during his lifetime. Their collaboration was evidently a close one, and her continuation of the studio's output speaks to her own artistic skill and her dedication to preserving the aesthetic they had developed together. This has sometimes led to discussions among collectors and historians regarding the precise attribution of works produced around the time of Ernest's death and immediately after, particularly those signed "Gamy." However, the "Gamy" signature is generally accepted as indicating Marguerite's primary authorship or completion of a piece. Her work maintained the dynamism and thematic focus established by Ernest, ensuring the continued availability of these popular images.

The Commercial Dimension: Art in Service of Industry

Montaut's art was not created in a vacuum; it was intrinsically linked to the burgeoning automotive and aviation industries. His prints served not only as artistic representations but also as powerful promotional tools. Manufacturers of automobiles, tires (like Michelin), carburetors, spark plugs, and other automotive components often commissioned or utilized his imagery.

His work appeared as advertisements, posters, and illustrations in popular magazines. This commercial aspect does not diminish its artistic merit; rather, it highlights Montaut's ability to bridge the gap between fine art and commercial illustration. He understood the aspirational power of these new technologies and translated it into compelling visuals that resonated with a wide audience. His art helped to build the mystique and excitement around these new machines, contributing to their public acceptance and desirability.

Montaut in the Context of His Contemporaries

Ernest Montaut's work can be situated within several artistic currents of his time. The Belle Époque saw the flourishing of poster art, with artists like Jules Chéret, often called the "father of the modern poster," transforming street advertising into an art form. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec captured the vibrant, sometimes gritty, life of Parisian cabarets and racetracks with a distinctive graphic style. Alphonse Mucha became the icon of Art Nouveau with his elegant, decorative posters. While Montaut's style was more illustrative and less overtly stylized than Mucha's, he shared with these artists a commitment to dynamic composition and the use of printmaking for wider dissemination.

In the realm of illustration depicting modern life and technology, other artists were also active. Georges Goursat, known as "Sem," was a famous caricaturist who often depicted Parisian society, including its fascination with automobiles. Théophile Steinlen, another prolific printmaker and poster artist, focused more on social realism but also created memorable advertisements.

Looking slightly beyond Montaut's lifespan, the Italian Futurists, including Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (the movement's founder), Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo, would later take the obsession with speed, machines, and dynamism to an even more radical, abstract level. While Montaut was not a Futurist, his pioneering efforts to visually articulate speed can be seen as a precursor to their more avant-garde explorations. His work, though representational, shared the Futurists' exhilaration with the machine age. One might even draw a distant parallel to earlier artists who sought to capture motion, such as Théodore Géricault with his dramatic paintings of charging horses, though Montaut's subject was the entirely new realm of mechanical velocity. Other illustrators of the period, such as René Vincent or Geo Ham (Georges Hamel), who came slightly later, would continue the tradition of dynamic automotive art, clearly influenced by the visual vocabulary Montaut helped establish.

The artists listed in some exhibition catalogs alongside Montaut, such as Roparalleled, Nuy, Roowyll (possibly a misspelling or lesser-known figure), Caldor, Aldo, Brieuf, Duvert, and Jobbe du Val, indicate a community of illustrators and printmakers working on similar commercial or popular themes, though Montaut's specific focus on speed and his distinctive style set him apart.

Challenges, Legacy, and Enduring Appeal

Ernest Montaut's premature death in 1909 undoubtedly cut short a career that was already making a significant mark. The continuation of his style by his wife, Marguerite "Gamy" Montaut, ensured that his artistic vision lived on for a time. However, the very nature of their production, with hand-coloring and variations between prints, sometimes presents challenges for precise dating and attribution, particularly for works produced around the transition period.

Despite these minor complexities, Montaut's legacy is secure. He is recognized as a key figure in the visual chronicling of the dawn of the automotive and aviation ages. His invention and popularization of speed lines had a lasting impact on illustration and graphic art. His prints are highly collectible today, valued not only for their artistic merit and historical significance but also for their nostalgic evocation of a pioneering era.

In the 1950s, a significant collection of Montaut's lithographs was donated by Eckert Ullmann to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, a testament to their recognized artistic and historical importance. His work continues to be celebrated in exhibitions and publications dedicated to automotive art, poster design, and early twentieth-century illustration.

Conclusion: An Artist of a New Age

Ernest Montaut was more than just an illustrator of machines; he was a visual poet of the nascent age of speed. With a keen eye, innovative techniques, and a palpable enthusiasm for his subjects, he captured the thrill, the danger, and the sheer exhilaration of humanity's first forays into high-speed mechanical transport. His dynamic compositions, vibrant colors, and pioneering depiction of motion created a visual language that not only defined his era but also left an indelible mark on the way speed and action would be portrayed in art and popular culture for decades to come. His tragically short career yielded a body of work that remains a vivid and exciting window onto a time when the roar of an engine and the sight of a machine conquering distance or air represented the cutting edge of human endeavor.