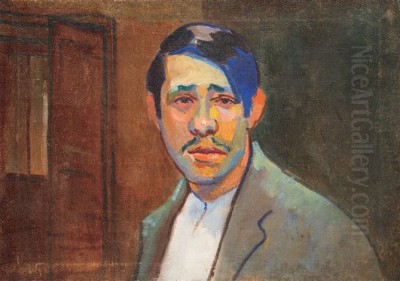

Erno Tibor stands as a significant, albeit tragically curtailed, figure in early 20th-century Hungarian and, by extension, Central European art. A painter whose life was framed by the shifting borders and profound upheavals of his time, Tibor's work offers a poignant window into the everyday existence, the landscapes, and the artistic currents that shaped his world. His journey from the vibrant cultural hub of Nagyvárad to the artistic heart of Paris, and his eventual, devastating end in the Holocaust, paints a picture of an artist deeply engaged with his environment, whose legacy continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Nagyvárad

Born on February 28, 1885, in Nagyvárad, Hungary (now Oradea, Romania), Erno Tibor emerged from a Jewish family into a city renowned for its rich cultural tapestry and intellectual ferment. Nagyvárad, at the turn of the century, was a crucible of artistic and literary innovation, a place where Hungarian, Romanian, and Jewish cultures intermingled, creating a dynamic atmosphere conducive to creative pursuits. It was in this stimulating environment that Tibor's artistic inclinations first took root.

His initial artistic education likely occurred locally, absorbing the prevailing academic and realist traditions. However, the winds of change were blowing across European art, and the allure of more modern expressive forms would soon draw him towards the major art centers. Budapest, the Hungarian capital, was his next destination, where he would have encountered a burgeoning art scene grappling with the legacy of 19th-century naturalism and the exciting new possibilities offered by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Artists like Károly Ferenczy and the Nagybánya artists' colony were already pioneering plein-air painting and Impressionistic approaches in Hungary, creating a fertile ground for young talents like Tibor.

Parisian Sojourn: Embracing Impressionism at the Académie Julian

The true turning point in Tibor's artistic development came with his move to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. He enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that attracted students from across the globe, offering a more liberal alternative to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts. Here, Tibor studied under Jean-Paul Laurens, a respected academic painter known for his historical scenes. While Laurens' own style was rooted in academic tradition, the environment of Paris and the Académie Julian exposed Tibor to a kaleidoscope of avant-garde movements.

It was in Paris that Tibor fully embraced Impressionism and subsequently Neo-Impressionism. The works of Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, with their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere, profoundly influenced his vision. He learned to lighten his palette, to use broken brushstrokes, and to paint en plein air, directly observing the effects of light on his subjects. The scientific approach to color and light advocated by Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac also left its mark, evident in a more structured application of color in some of his works. This period was crucial for Tibor, allowing him to synthesize academic discipline with modern sensibility.

Return to Nagyvárad: The "Painter of the City" and "Holnap"

Armed with new techniques and a refined artistic vision, Erno Tibor returned to his native Nagyvárad. He quickly became a prominent figure in the local art scene, so much so that he earned the affectionate moniker "the painter of Nagyvárad." His Parisian experiences infused his work with a fresh vibrancy that distinguished him.

A testament to his engagement with the cultural life of his city was his involvement in the founding of "Holnap" (Tomorrow), an influential artistic and literary society. This group, active in the early 20th century, sought to promote modernism in Hungarian literature and art, and Tibor was a key artistic voice within it. He associated with other notable local artists such as Alfred Macalik, István Balogh, Leon Alex, and Nicolae Irimie, who collectively contributed to Oradea's reputation as a significant provincial art center during the interwar period, especially after the city became part of Romania following World War I.

Artistic Style: Realism, Impression, and Social Observation

Erno Tibor's artistic style is best characterized as a fusion of realism with Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist techniques. His foundational training provided him with a strong grasp of drawing and composition, ensuring that his explorations of light and color were always grounded in solid structure. He was not an Impressionist in the purely optical sense of dissolving form into light, but rather used Impressionistic brushwork and color theory to enhance the realism and emotional impact of his subjects.

His thematic concerns were deeply rooted in the life around him. Tibor was a keen observer of everyday existence, frequently depicting scenes of markets bustling with activity, peasants toiling in the fields, workers engaged in their labor, and fishermen by the water. These subjects reflect a humanist sensibility, an interest in the dignity of ordinary people and their connection to their environment. His landscapes, whether rural vistas or cityscapes, were rendered with an eye for atmospheric effects, capturing the specific quality of light at different times of day and in varying weather conditions.

His color palette was typically vivid and expressive, though he could also achieve subtle harmonies. Later in his career, his work reportedly showed an increasing refinement in color relationships and a greater attention to detail, suggesting a continuous evolution and search for expressive precision. He was adept at conveying mood, whether the quietude of a rural scene or the vibrant energy of a marketplace.

Navigating a World at War: Artistic Resilience in WWI

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought widespread disruption to Europe, but Erno Tibor demonstrated remarkable resilience. He continued to paint, even reportedly at the front lines, capturing the stark realities and perhaps the fleeting moments of normalcy amidst the conflict. This period underscores his dedication to his craft, viewing art not merely as a profession but as an essential means of processing and responding to the world.

Following the war, which saw the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolve and Nagyvárad (Oradea) become part of Romania, Tibor remained active. He organized exhibitions of his work, seeking to share his artistic vision with a public grappling with the aftermath of war and significant geopolitical shifts. His efforts to promote his art during such challenging times speak to his proactive role in the cultural life of his community.

Exhibitions and Growing Recognition

Erno Tibor's work gained recognition beyond his immediate circle. He exhibited not only in Oradea and Budapest but also in other European cities, including Bucharest, Berlin, and Gothenburg. His participation in exhibitions in Bucharest, such as the official Salons, placed him alongside prominent Romanian artists of the era, including Ion Theodorescu-Sion, a leading figure in Romanian modernism known for his Symbolist and Neo-Traditionalist works; Gheorghe Petrașcu, celebrated for his richly textured landscapes and still lifes; and Theodor Pallady, an aristocrat painter whose elegant post-impressionist style was influenced by his time in Paris and his friendship with Henri Matisse.

These exhibitions were crucial for establishing his reputation and for engaging in a broader artistic dialogue. The critical reception of his work, often positive, acknowledged his skillful handling of color and his ability to capture the essence of his subjects. His travels, particularly to France and Italy, further enriched his artistic vocabulary, exposing him to diverse landscapes and artistic traditions that he absorbed into his evolving style.

The Darkening Years: Persecution and Tragic End

The rise of fascism and antisemitism in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s cast a dark shadow over Erno Tibor's life and career. As a Jew, he faced increasing persecution and restrictions. The vibrant cultural life he had known was systematically dismantled by oppressive regimes. Despite the growing danger, Tibor continued to live and work, a testament to his deep connection to his homeland.

The horrors of World War II ultimately consumed him. In 1944, Erno Tibor was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, a name synonymous with the barbarity of the Holocaust. From Auschwitz, he was likely moved to another Nazi labor camp, where he perished in the same year. His life, so rich in artistic creation and engagement, was brutally cut short by the genocidal madness that swept across Europe. The loss of Tibor, like that of countless other artists and intellectuals, was an immeasurable tragedy for European culture. His fate mirrors that of other Jewish artists, such as Felix Nussbaum or Charlotte Salomon, whose promising careers were extinguished by the Nazi regime.

Artistic Philosophy and Anecdotes: The Painter Who Wouldn't Sell

An intriguing aspect of Erno Tibor's persona was his reported reluctance, or even outright refusal, to sell his paintings. This stance, if accurately reported, suggests a deeply personal and perhaps idealistic view of art. For Tibor, his paintings may have been more akin to children or extensions of his own being, rather than commodities for the market. He might have believed that art's primary value lay in its creation and its capacity to communicate, rather than in its monetary worth.

This attitude, while perhaps impractical from a financial standpoint, highlights a certain integrity and a profound attachment to his work. It sets him apart from many artists who necessarily engage with the art market for their livelihood. This characteristic adds another layer to the understanding of Tibor as an artist driven by an inner compulsion to create and share, rather than by commercial ambition.

Another poignant anecdote from his life concerns an attempted escape during his deportation in WWII. It is said that he managed to create an opening in the floor of the train wagon using a rusty hammer, but other prisoners did not follow him. He eventually made his way back to his wife in Békescsaba (a town in Hungary), a brief, desperate reunion before the inevitable. This story, if true, speaks volumes about his courage and will to survive even in the face of unimaginable horror.

Legacy and Impact on Art History

Erno Tibor's premature death means his full artistic potential may never have been realized. Nevertheless, the body of work he left behind secures his place as an important Hungarian Impressionist painter and a significant figure in the art history of the region, including Romania, due to Oradea's historical context. His paintings serve as valuable documents of a bygone era, capturing the landscapes, people, and social fabric of early 20th-century Central Europe.

His art is appreciated for its vibrant color, its sensitive portrayal of everyday life, and its successful synthesis of realist foundations with Impressionist innovations. He contributed to the dissemination of modern artistic ideas in his native region, influencing local artists and enriching the cultural landscape. His work can be seen in dialogue with other Hungarian Impressionists like József Rippl-Rónai or Béla Iványi-Grünwald, who also adapted French modernism to a Hungarian context.

The tragic circumstances of his death also imbue his work with a particular poignancy. His life story is a stark reminder of the devastating impact of war and persecution on artistic creation and on individual human lives. Like many artists whose lives were cut short by the Holocaust, such as the Czech painter Bedřich Fritta or the Polish-Jewish artist Bruno Schulz (though Schulz was primarily a writer and graphic artist), Tibor's legacy is twofold: his artistic achievement and his status as a victim of one of history's darkest chapters.

Today, Erno Tibor's paintings are held in various collections, and his work continues to be studied and appreciated for its artistic merit and historical significance. He represents a generation of artists who navigated complex cultural identities and tumultuous political changes, striving to create beauty and meaning in a world teetering on the brink of chaos.

Conclusion: A Light Undimmed by Darkness

Erno Tibor's life was a journey through light and shadow – the luminous light of Impressionism that he so skillfully wielded, and the encroaching darkness of war and genocide that ultimately consumed him. As an art historian, one looks at his canvases depicting bustling markets, serene landscapes, and the quiet dignity of working people, and sees not only a talented painter but also a chronicler of his time. His commitment to his art, his engagement with his community, and his tragic end all contribute to a legacy that is both artistically significant and deeply human.

His work stands as a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the ephemeral beauty of the world and the resilience of the human spirit, even in the face of unimaginable adversity. Erno Tibor, the "painter of Nagyvárad," remains a vital voice from a lost world, his canvases continuing to speak to us of life, light, and the enduring quest for artistic expression. His contributions to Hungarian and Romanian art ensure that his name, and his vision, will not be forgotten.