Erskine Nicol stands as a significant, albeit complex, figure in the narrative of 19th-century British and Irish art. Born in Scotland but forging his artistic identity through the lens of Irish life, Nicol became one of the most popular painters of his era, specializing in genre scenes that captured the humour, hardship, and distinct character of rural Ireland. His work, widely disseminated through exhibitions and print, shaped perceptions of Ireland, particularly in Britain and America, while also engaging with the pressing social realities of his time. This exploration delves into the life, work, style, and legacy of an artist whose canvases continue to provoke discussion about representation, identity, and the role of art in reflecting society.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Scotland

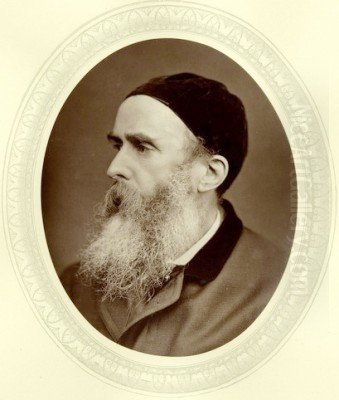

Erskine Nicol was born in Leith, the port district of Edinburgh, Scotland, on July 3, 1825. His father, James Nicol, was involved in commerce, potentially as a wine merchant, and initially hoped his son would follow a similar path into business. However, young Erskine displayed a clear aptitude and passion for art from an early age. Against his father's initial wishes, but perhaps encouraged by his mother, Mary Muirhead (sometimes noted as being of French descent, adding a layer to his cultural background), Nicol pursued his artistic inclinations.

At the remarkably young age of twelve, around 1837, he enrolled at the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh. This institution was a cornerstone of Scottish art education, boasting esteemed alumni such as Sir David Wilkie, whose own genre scenes of Scottish life undoubtedly provided a precedent for Nicol's later focus. Under the tutelage available at the Academy, Nicol honed his skills in drawing and painting, laying the technical foundation for his future career. After completing his studies, he secured a position as an art teacher at Leith High School, seemingly embarking on a stable, if perhaps conventional, path.

The Pivotal Move to Ireland

The trajectory of Nicol's life and art changed decisively in 1846. At the age of 21, seeking greater opportunities or perhaps driven by a youthful desire for adventure and independence, he resigned from his teaching post in Leith. He travelled to Ireland, initially settling in Dublin. This move was undertaken in partnership with his cousin, Peter Cleland. Their initial ambition was to establish a school together in the Irish capital, but this venture ultimately proved unsuccessful, forcing Nicol to find alternative means of support and artistic direction.

His arrival in Ireland coincided with a period of profound crisis and transformation: the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór, 1845-1849) was ravaging the country. Although his initial years were marked by financial struggle, this period immersed Nicol in the realities of Irish life at a critical juncture. He found work as a teacher and began to travel, particularly in the Midlands and West of Ireland. It was during these formative years, between 1846 and roughly 1850/1851, that he gathered the experiences and observations that would become the bedrock of his artistic practice for the rest of his life. The landscapes, the people, their customs, hardships, and resilience, made an indelible impression.

Forging an Artistic Identity: Genre Painting and Irish Themes

Finding his niche, Nicol turned his focus almost exclusively to depicting scenes of Irish rural life. He embraced genre painting – the depiction of scenes from everyday life – a tradition with strong roots in Dutch and Flemish art of the 17th century, exemplified by masters like Adriaen Brouwer, David Teniers the Younger, and Jan Steen, who often depicted peasant life with robust humour and detail. Nicol adapted this tradition to the specific context of 19th-century Ireland, developing a distinctive style that blended meticulous observation with a pronounced sense of narrative and, frequently, humour.

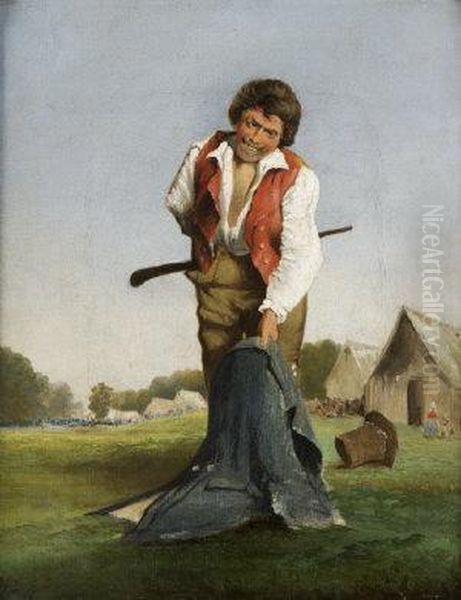

His approach was fundamentally anecdotal. He excelled at capturing moments – a market day transaction, a gathering at a pub, a religious festival, a quiet domestic scene, a moment of contemplation or dispute. His canvases are often populated by vividly characterized figures, typically drawn from the Irish peasantry. He paid close attention to details of dress, setting, and physiognomy, grounding his scenes in a tangible reality. However, his realism was often infused with humour, sometimes gentle, sometimes bordering on caricature or satire.

This humorous, sometimes stereotypical, portrayal of the Irish, particularly the figure often referred to as "Paddy," became a hallmark of his work and a source of its immense popularity, especially among British audiences. It also, inevitably, attracted criticism, both during his lifetime and subsequently, for potentially reinforcing negative stereotypes prevalent in Victorian Britain. Yet, Nicol's work cannot be dismissed solely as caricature. Within the humour, there is often genuine warmth, empathy, and a clear fascination with the resilience and distinct cultural identity of his subjects. He also did not shy away from depicting the harsher realities, including poverty and the spectre of emigration that haunted post-Famine Ireland.

Artistic Style: Humour, Realism, and Narrative

Nicol's technical skill was considerable. He typically worked in oils, employing a detailed, polished finish characteristic of much Victorian academic painting. His compositions are carefully constructed, often featuring multiple figures interacting within a well-defined space, whether an interior or a landscape setting. He had a strong sense of narrative, ensuring that each scene told a story, often with a clear focal point and supporting details that enriched the viewer's understanding.

His use of humour was multifaceted. It could be situational, arising from the interactions between characters, or character-based, stemming from exaggerated expressions or postures. This comedic element made his work highly accessible and entertaining, contributing significantly to his commercial success. It set him apart from contemporaries engaged in more overtly serious social realism, such as Luke Fildes or Frank Holl in England, whose depictions of poverty were generally more sombre.

While often compared to his Scottish predecessor Sir David Wilkie in terms of subject matter (rural genre scenes), Nicol's humour was perhaps broader, his characterizations sometimes less individualized and more reliant on types. His work also finds parallels with English contemporaries like William Powell Frith, particularly in the ambition of his larger, multi-figure compositions like Donnybrook Fair, which echo the bustling energy of Frith's famous scenes like Derby Day or The Railway Station. Both artists shared a talent for marshalling complex scenes filled with anecdotal detail, capturing a cross-section of society.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Several paintings stand out as representative of Nicol's oeuvre and thematic interests:

_St Patrick's Day_ (1856): This work exemplifies Nicol's engagement with Irish cultural and religious life. It depicts a lively scene associated with Ireland's patron saint's day, likely showing villagers celebrating, possibly with music and drink. Such scenes allowed Nicol to explore communal identity and traditions, often through a humorous lens that focused on the perceived exuberance of Irish Catholic festivities. The work highlights his ability to capture the atmosphere of a specific cultural moment.

_Donnybrook Fair_ (1859): One of his most ambitious and famous works, this large canvas captures the notorious, boisterous atmosphere of the historic Dublin fair, known for its revelry and frequent brawls. Nicol populates the scene with a multitude of figures engaged in various activities – drinking, dancing, arguing, trading – creating a panoramic view of Irish peasant life at its most unrestrained. It showcases his skill in composing complex scenes and his fascination with the energy and perceived lack of inhibition of his subjects.

_The Tenant_ (also known as _An Irish Tenant Farmer_): Works depicting tenant farmers, often in moments of contemplation, negotiation, or hardship, touched upon the critical issue of land tenure in Ireland. These paintings could subtly allude to the precariousness of rural life and the power dynamics between tenants and landlords, a theme central to Irish social history in the 19th century.

_Looking Out for a Safe Investment_ (c. 1865): This title suggests a scene involving financial prudence or perhaps suspicion, often featuring shrewd-looking peasant figures. Such works played on stereotypes of peasant cunning while also potentially reflecting the economic anxieties of the time.

_Paying the Rent_: Another recurring theme, depictions of rent day were fraught with social significance, highlighting the economic dependence and potential vulnerability of the tenant class. Nicol often imbued these scenes with a mix of tension and character study.

_Missed It_ (1868): Often depicting a scene of disappointment or a missed opportunity, perhaps related to emigration or a simple daily mishap, this title points to Nicol's interest in capturing relatable human emotions within an Irish setting.

Beyond these specific examples, Nicol frequently painted scenes set in pubs, cabins, and markets, featuring priests, matchmakers, musicians, and drinkers. His works collectively form a vast visual catalogue of Irish rural archetypes and activities as perceived through his particular lens.

The Role of Self-Portraiture

Erskine Nicol also produced a number of self-portraits throughout his career, which offer intriguing insights into his self-perception and his relationship with his adopted subject matter. Unlike the formal self-portraits common in the tradition of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn, Nicol often depicted himself within an Irish context, sometimes even adopting elements of Irish peasant dress or appearing alongside Irish figures.

A notable example is Self-Portrait with Peasant Companions (1855). Here, Nicol places himself directly within the world he paints, suggesting a level of identification or immersion. These self-portraits can be interpreted in various ways: as an assertion of his authority as an observer and interpreter of Irish life, as an exploration of his own identity caught between his Scottish origins and his Irish experiences, or even as a playful adoption of the very types he often depicted. They add a layer of complexity to his artistic persona, showing an artist consciously positioning himself in relation to his subjects.

Reception, Reputation, and Recognition

Erskine Nicol achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. After his initial years in Ireland, he returned to Britain, first settling back in Edinburgh around 1851 and later moving to London in 1862, although he continued to visit Ireland regularly to gather material. His paintings were frequently exhibited at major institutions, most notably the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh and the Royal Academy (RA) in London.

His popularity with the public and collectors was immense. His humorous and narrative scenes struck a chord, and their perceived authenticity (however debated) made them highly sought after. He was elected an Associate of the RSA in 1851 and became a full Academician (RSA) in 1859. His success in London was confirmed by his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1866. This official recognition cemented his status within the British art establishment.

His works were widely reproduced as prints and used as illustrations, notably for publications like S.C. Hall's Handbooks for Ireland and books focusing on Irish character, such as Irish Life and Character. This dissemination further boosted his fame and embedded his particular vision of Ireland in the popular imagination, both in Britain and across the Atlantic in the United States, where there was a large Irish diaspora and considerable interest in images of the "Old Country."

However, his work was not without its critics. Some commentators, particularly those aligned with Irish nationalist sentiments later in the century, took issue with his tendency towards caricature and felt his depictions pandered to British prejudices. The debate over whether Nicol was a sympathetic observer or a purveyor of the "Stage Irishman" stereotype continues to inform discussions of his work today. He remains a figure whose popularity was undeniable, but whose legacy is viewed through the critical lens of post-colonial studies and evolving understandings of cultural representation.

Nicol in the Wider Context of Victorian Art

Placing Erskine Nicol within the broader landscape of 19th-century art helps to understand his position. His commitment to genre painting aligns him with a strong current in Victorian art that valued narrative, detail, and scenes of contemporary life. While distinct in subject and tone, his work shares this focus with artists like William Powell Frith, Augustus Egg (known for moralizing narrative series), and even the social realists like Fildes and Holl, all of whom sought to reflect aspects of the society around them.

His Scottish roots connect him to a national tradition of genre painting strongly associated with Sir David Wilkie and later artists like Thomas Faed. Nicol continued this tradition but transferred its focus to Ireland, creating a unique Scottish-Irish artistic hybrid.

Compared to the dominant trends of the mid-to-late Victorian era, such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (e.g., Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt) with their emphasis on medievalism, literary themes, and intense detail, or the later Aesthetic Movement, Nicol's work appears more traditional and populist. He largely remained untouched by the influence of French Impressionism that began to affect British art towards the end of his career.

Within the specific context of Irish art, Nicol was an outsider who became one of the most prominent depictors of the country. He worked during a period when Irish artists like Frederic William Burton, Walter Osborne, and Nathaniel Hone the Younger were also active, though often exploring different styles and themes (Burton's detailed watercolours, Osborne's later move towards Impressionism, Hone's landscape focus). Nicol's concentration on peasant genre scenes gave him a distinct, highly visible, and commercially successful niche.

Later Life and Legacy

After moving to London in 1862, Nicol established a successful studio, first in St John's Wood and later settling in Feltham, Middlesex. He continued to paint Irish subjects, drawing on his earlier experiences and regular return visits. His popularity endured, and he maintained a prolific output until his health began to decline. He passed away at his home, The Dell, in Feltham, on March 8, 1904, at the age of 78.

Erskine Nicol's legacy is complex. He was undoubtedly a highly skilled painter and a master storyteller in paint. His works provide a vivid, if selective and often humorous, window onto aspects of 19th-century Irish rural life. For many viewers, particularly during his lifetime, his paintings offered engaging narratives and relatable characters. His commercial success and official recognition attest to his mastery of a popular idiom.

However, his legacy is also intertwined with the problematic history of Anglo-Irish relations and cultural stereotypes. Modern assessments must grapple with the extent to which his work, intentionally or not, reinforced simplistic or demeaning views of the Irish people. Yet, even within the humour and occasional caricature, glimpses of genuine hardship, resilience, and cultural distinctiveness emerge, suggesting a more nuanced engagement than simple prejudice might allow.

His influence can be seen in the enduring popularity of Irish genre scenes and in the way his work contributed to the visual iconography of Ireland. His paintings remain important documents, not just of how Irish life was lived, but also of how it was perceived and represented by an outsider who dedicated his career to its depiction. Artists who followed, whether embracing or reacting against his style, had to contend with the powerful, pervasive imagery Nicol had created. He remains a key figure for understanding the intersection of art, identity, and social history in 19th-century Britain and Ireland.

Conclusion

Erskine Nicol occupies a unique space in art history – a Scotsman who became the pre-eminent painter of Irish life for a generation. His technical proficiency, narrative skill, and deployment of humour brought him widespread acclaim and commercial success. His paintings, from bustling fairs like Donnybrook to intimate cabin scenes, captured the imagination of the Victorian public and left an indelible mark on the visual representation of Ireland. While contemporary perspectives rightly question the element of caricature and stereotype in his work, his canvases remain compelling documents of their time, reflecting both the social realities he observed and the cultural attitudes through which he filtered them. Nicol's art continues to engage viewers and historians, prompting reflection on the complexities of seeing and representing another culture.