John Watson Nicol, a notable figure in the Scottish and British art scenes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, carved a niche for himself through his evocative depictions of historical events, genre scenes, and subjects imbued with a distinct sense of narrative and emotion. Born in Edinburgh on January 12, 1856, he was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age, being the son of the esteemed painter Erskine Nicol and Janet Watson, also known as Jessie Watson. This familial connection to the art world undoubtedly played a significant role in shaping his early inclinations and subsequent career. John Watson Nicol passed away in 1926, leaving behind a body of work that continues to offer insights into the cultural and social preoccupations of his time, particularly concerning Scottish and Irish identities and the poignant theme of emigration.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Growing up in Edinburgh, a city with a rich artistic and intellectual heritage, John Watson Nicol would have been exposed to a vibrant cultural milieu. His father, Erskine Nicol (1825-1902), was a highly successful painter, particularly renowned for his often humorous, sometimes stereotypical, depictions of Irish peasant life. The elder Nicol's success and established presence in the art world likely provided both an inspiration and a standard for John Watson. While specific details of his formal artistic training are not extensively documented in the provided information, it is common for artists of that era, especially those with an artist parent, to receive initial instruction at home before potentially attending local art academies, such as the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh, which had nurtured talents like Sir David Wilkie and later, William McTaggart.

The influence of Erskine Nicol on his son's work is discernible, particularly in the choice of subject matter that sometimes touched upon Irish themes. However, John Watson Nicol developed his own distinct voice, often imbuing his subjects with a more melancholic or historically reflective quality, moving beyond the overt anecdotalism that characterized some of his father's popular pieces. His mother, Janet Watson, though less famed, contributed to the artistic lineage. The family environment, steeped in the practice and discussion of art, would have been a crucible for his developing talents.

Relocation and Career Development in London

Like many ambitious Scottish artists of his generation, John Watson Nicol eventually made the move to London, the epicentre of the British art world. This relocation offered greater opportunities for exhibition, patronage, and engagement with a broader artistic community. In London, he established his family, marrying Charlotte Eppie Linton, and they had two sons, John and Hamish, one of whom reportedly followed the family tradition and became an artist, working alongside his father and, presumably, in the shadow of his grandfather Erskine Nicol's significant reputation.

Nicol became a regular exhibitor at prestigious venues, most notably the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Acceptance and display at the Royal Academy were crucial for an artist's career progression and reputation during the Victorian era. His works were also shown at other art societies and galleries, indicating a consistent professional practice and a degree of recognition within the art establishment. His subject matter often revolved around historical narratives, literary themes, and genre scenes that captured aspects of Scottish and Irish life, reflecting a deep engagement with his cultural heritage.

Themes and Subjects in Nicol’s Art

John Watson Nicol’s oeuvre demonstrates a recurring interest in themes of history, cultural identity, and human emotion, often explored through a Scottish or Irish lens. His approach to these subjects evolved, showcasing a sensitivity to the nuances of his chosen narratives.

Scottish Heritage and The Highland Clearances

A profound connection to Scottish history and culture is evident in Nicol's work. He was painting during a period when Scottish identity was a subject of both romantic idealization and critical re-examination. The aftermath of events like the Highland Clearances – the forced displacement of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands during the 18th and 19th centuries – cast a long shadow and provided poignant subject matter for artists. These themes of loss, displacement, and emigration resonated deeply within the Scottish consciousness and found expression in the art of the period. Artists like Thomas Faed (1826-1900) had powerfully addressed such subjects, for instance, in his famous work "The Last of the Clan" (1865), which depicted a group of emigrants leaving their homeland. Nicol’s work often tapped into this vein of historical sorrow and cultural memory.

Irish Themes and Emigration

Following in his father's footsteps to some extent, John Watson Nicol also addressed Irish subjects. However, his approach often differed. While Erskine Nicol's depictions of Irish life, though popular, sometimes veered into caricature, reflecting prevalent stereotypes, John Watson Nicol's interpretations, particularly in his mature work, could convey a deeper empathy. The provided information suggests that his early works might have contained elements of humour and satire, but his style evolved towards a more sympathetic and serious tone, especially when dealing with the hardships faced by Irish emigrants. The Great Famine (An Gorta Mór) of the 1840s had led to mass emigration from Ireland, and the social and economic conditions in its aftermath continued to be a source of concern and artistic commentary throughout the latter half of the 19th century. Artists like the Irish-American painter Daniel MacDonald (c. 1820-1853) had earlier captured the stark realities of the famine and emigration.

Genre Scenes and Narrative Painting

Nicol was, in essence, a narrative painter, a tradition that held considerable sway in Victorian art. His works often tell a story or evoke a specific mood through the careful arrangement of figures, setting, and incident. This aligns with the broader trends in British art of the period, where painters like William Powell Frith (1819-1909) with his panoramic scenes of modern life (e.g., "The Derby Day," "The Railway Station"), or Augustus Egg (1816-1863) with his moralizing triptych "Past and Present," captivated audiences with their storytelling abilities. Nicol’s genre scenes, whether set in a Highland croft, an Irish cottage, or aboard an emigrant ship, aimed to engage the viewer emotionally and intellectually.

Representative Masterpiece: "Lochaber No More"

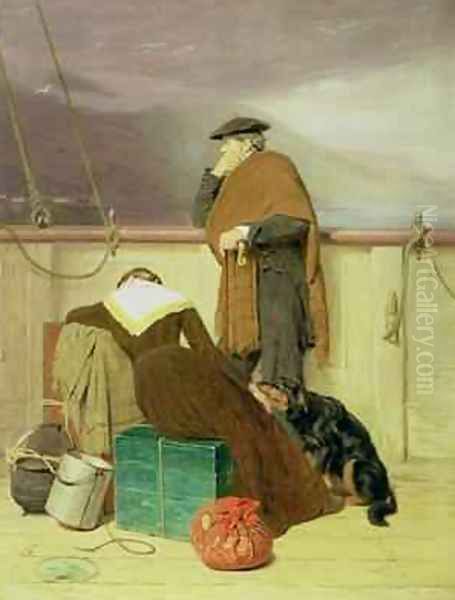

Among John Watson Nicol's most significant and enduring works is "Lochaber No More," painted in 1883. This oil painting is widely considered his masterpiece and serves as a poignant visual elegy to the experience of Scottish emigration, particularly in the wake of the Highland Clearances. The title itself, "Lochaber No More," is a direct reference to a well-known Scottish lament, evoking a deep sense of loss and farewell to one's native land.

The painting depicts the interior of a ship's cabin or steerage area, where a family or group of Highland emigrants are journeying to a new, uncertain future. A central male figure, perhaps the patriarch, stands pensively, his gaze distant, lost in thought or gazing out towards a sea that represents both passage and separation. A woman, possibly his wife, is shown engaged in some domestic task, perhaps sorting belongings, her posture suggesting resignation or quiet sorrow. The atmosphere is subdued, rendered in a palette of muted colours that enhance the melancholic mood. The cramped conditions and the somber expressions of the figures convey the hardship and emotional toll of leaving home.

"Lochaber No More" is praised for its sensitive portrayal of human emotion and its historical resonance. The composition is carefully constructed to draw the viewer into the scene, fostering a sense of empathy for the figures. The play of light and shadow, the detailed rendering of textures, and the psychological depth of the characters contribute to the painting's power. It has been compared in theme and sentiment to Thomas Faed's "The Last of the Clan," both works capturing the profound sense of displacement that marked this era of Scottish history. The painting is now part of the Fleming Collection (Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation), which specializes in Scottish art, and its inclusion there underscores its importance as a representation of a critical period in Scottish social history. It has also been suggested that the work was exhibited at the Royal Academy, further cementing its status. The Gordon Highlanders Museum has also been mentioned as a place where its display would be fitting, highlighting its cultural significance.

Other Notable Works and Artistic Endeavors

While "Lochaber No More" stands as his most celebrated piece, John Watson Nicol produced other works that reflect his artistic interests. One such painting is "Rob Roy and the Bailie." The title suggests a scene inspired by Sir Walter Scott's famous novel "Rob Roy" (1817), which was a popular source of inspiration for many 19th-century artists. A black and white reproduction of this painting was reportedly used as a cover for "The Bookman" magazine in 1930, indicating its recognition and appeal decades after Nicol's primary period of activity. This connection to literary themes was common among Victorian painters, who often drew upon popular novels, poetry, and historical accounts for their subject matter.

There is also mention of a work titled "The Old Soldier (Roddick James)" or "The Revenge" (1908), for which a soldier named James Roddick, who lived in Edinburgh, may have served as a model. This suggests Nicol's interest in character studies and perhaps in themes of military life or veteran experience, subjects also explored by artists like Lady Butler (Elizabeth Thompson, 1846-1933) in her dramatic battle scenes and depictions of soldiers. The specificity of the model's name, if accurate, points to Nicol's practice of working from life to achieve a sense of realism and individuality in his figures.

Artistic Style and Technique

John Watson Nicol's artistic style can be broadly characterized as Victorian narrative realism. He demonstrated a proficient handling of oil paint, with a keen eye for detail, texture, and the effects of light. His compositions are generally well-structured, designed to convey the narrative or emotional core of the scene effectively.

In "Lochaber No More," for instance, his use of a relatively subdued palette, dominated by earthy tones and cool blues and greys, contributes significantly to the painting's melancholic atmosphere. The brushwork is controlled and descriptive, allowing for a clear rendering of figures, clothing, and setting. He paid close attention to facial expressions and body language to convey the inner states of his characters, a hallmark of successful narrative painting. This ability to capture psychological nuance is what elevates his work beyond mere illustration.

His style shows an affinity with other Scottish artists of the period who focused on genre and historical scenes, such as Thomas Faed, Erskine Nicol (his father), and perhaps the earlier work of Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), who was a pioneer of Scottish genre painting. While not an innovator in the modernist sense – his career largely predates the major modernist upheavals – Nicol worked skillfully within the established conventions of late Victorian academic painting, prioritizing storytelling, emotional resonance, and a degree of realism that made his subjects accessible and relatable to his audience. He was less experimental than, for example, the contemporary Glasgow Boys (e.g., James Guthrie, John Lavery), who were exploring more impressionistic and plein-air techniques.

Contemporaries and the Wider Artistic Milieu

John Watson Nicol worked during a dynamic period in British art. The Royal Academy, where he exhibited, was still the dominant institution, though its authority was increasingly being challenged by new movements and exhibiting societies. Narrative painting, historical subjects, and social realism were prominent genres.

His focus on themes of emigration and social conditions aligns him with other Victorian artists who addressed the "Condition of England" question or the plight of the marginalized. Painters like Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914), with works such as "Hard Times" or "On Strike," and Luke Fildes (1843-1927), known for "Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward," brought social issues to the forefront of public consciousness through their art. Ford Madox Brown's (1821-1893) "The Last of England" is another iconic painting of emigration, though from an English rather than Scottish perspective, sharing a similar emotional weight with Nicol's "Lochaber No More."

Within the Scottish context, Nicol was a contemporary of artists like William McTaggart (1835-1910), celebrated for his expressive seascapes and scenes of rural life, often touching upon themes of childhood and the connection to nature. While McTaggart’s style became increasingly impressionistic, Nicol remained more rooted in a detailed, narrative approach. The aforementioned Thomas Faed was a significant figure whose work often paralleled Nicol's in its focus on Scottish rural life and emigration.

The influence of Pre-Raphaelitism, with its emphasis on detail, symbolism, and literary or historical subjects, had also left its mark on Victorian art, championed by artists like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt. While Nicol was not a Pre-Raphaelite, the general climate of detailed realism and narrative complexity fostered by the movement would have been part of the artistic air he breathed.

Personal Life and Family

The available information provides a few glimpses into John Watson Nicol's personal life. He was born into an artistic family, with his father, Erskine Nicol, being a prominent painter. He married Charlotte Eppie Linton, and they had at least two sons, John and Hamish. It is noted that one of his sons also became an artist, continuing the family's artistic legacy into a third generation. This suggests a household where art was not just a profession but a way of life. The family resided in London after Nicol's move from Edinburgh, placing them at the heart of the British art world. Beyond these facts, details about his personality or private life remain scarce in the provided summary, which is common for many artists of historical periods unless they left behind extensive correspondence or diaries, or were the subject of contemporary biographies.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

John Watson Nicol continued to work and exhibit into the early 20th century, with "The Revenge" dated to 1908. He passed away in 1926. While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries or those who broke more radically with tradition, his contribution to Scottish art and Victorian narrative painting is significant.

His legacy primarily rests on his ability to capture moments of historical and personal poignancy, particularly in works like "Lochaber No More." This painting, and others like it, serve as important visual documents of the social history of Scotland and the broader phenomenon of 19th-century emigration. They provide insight into the emotional experiences of individuals caught up in large-scale historical processes. The fact that "Lochaber No More" is highlighted for its potential influence on Australian literature, particularly in relation to the Irish immigrant experience, suggests that the themes he explored had a resonance that extended beyond the immediate British context.

The evaluation of his work, both in his time and subsequently, acknowledges its artistic merit, particularly its emotional depth and skillful execution within the narrative realist tradition. While some aspects of his biography or the attribution of certain works might be subject to ongoing scholarly discussion or clarification, his key paintings, especially "Lochaber No More," secure his place as a noteworthy artist who gave visual form to important aspects of Scottish and Irish cultural memory. His work continues to be valued by collectors and institutions specializing in Scottish and Victorian art.

Conclusion

John Watson Nicol stands as a significant Scottish artist of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Born into an artistic family, he developed a career marked by a sensitive engagement with historical and genre subjects, often focusing on themes of Scottish and Irish identity, emigration, and the human condition. His masterpiece, "Lochaber No More," remains a powerful and moving depiction of the sorrow and uncertainty of displacement, cementing his reputation as an artist capable of conveying profound emotion through his detailed and narrative style. Exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and other institutions, he was a recognized figure in the London art world. While perhaps overshadowed by artists who pursued more avant-garde paths, John Watson Nicol's work offers a valuable window into the artistic and social concerns of his time, and his contribution to the rich tapestry of British art, and Scottish art in particular, is worthy of continued appreciation and study. His paintings serve not only as aesthetic objects but also as historical documents that speak to the enduring themes of home, loss, and resilience.