Dame Ethel Walker stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century British art. A painter of considerable talent and versatility, she navigated a predominantly male art world with determination, achieving notable recognition in her lifetime. Her work, characterized by its lyrical quality, vibrant use of colour, and sensitive portrayal of the human form, particularly women, offers a unique blend of Impressionistic influences and a deeply personal vision. This exploration delves into her life, artistic development, key achievements, and the enduring legacy of a woman who carved her own path.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on June 9, 1861, in Edinburgh, Scotland, Ethel Walker was the youngest child of Arthur Abney Walker, a Yorkshireman, and his second wife, Isabella Ainslie Walker, who was Scottish. Her early years were spent in a comfortable middle-class environment. The family later relocated to London, which would become the primary hub for her artistic education and career. This move was pivotal, placing her in proximity to the burgeoning art schools and dynamic cultural scene of the capital.

Walker's artistic inclinations manifested early, but formal training commenced somewhat later in life compared to some of her contemporaries. She initially attended the Ridley School of Art. Her pursuit of artistic excellence then led her to the Putney School of Art. A crucial phase of her development occurred at the Westminster School of Art, where she studied under the influential Frederick Brown, who would later become a prominent figure at the Slade School. It was at Westminster that she began to truly hone her skills and develop a more defined artistic direction, absorbing the academic principles while also being exposed to newer, more progressive ideas filtering in from continental Europe.

The Slade School and Formative Influences

The next significant step in Ethel Walker's artistic education was her enrollment at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London. The Slade, under figures like Frederick Brown (who had moved from Westminster), Henry Tonks, and Philip Wilson Steer, was a crucible for many of Britain's most innovative artists at the turn of the century. Here, the emphasis was on drawing from life and a rigorous academic grounding, yet it also fostered an environment where new artistic currents, particularly French Impressionism, were discussed and absorbed.

During her time at the Slade and in the years that followed, Walker's style began to crystallize. She was profoundly influenced by the Impressionist movement, with its emphasis on light, colour, and capturing fleeting moments. Artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir undoubtedly left their mark. However, her influences were eclectic. She admired the decorative and symbolic qualities found in the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose large-scale, serene compositions resonated with her own developing interest in mural-like decorative pieces.

Furthermore, the bold colours and expressive forms of Post-Impressionist artists, notably Paul Gauguin, also played a role in shaping her aesthetic. Walker was also drawn to Asian art, particularly Chinese and Japanese painting and ceramics, which influenced her sense of composition, line, and a certain ethereal quality in some of her works. She herself mentioned an admiration for the Rococo grace of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, suggesting an appreciation for elegance and fluidity in painting. Unlike some of her contemporaries, she claimed not to be significantly influenced by Paul Cézanne or Vincent van Gogh, charting a more independent course.

The New English Art Club and Professional Recognition

A significant milestone in Ethel Walker's career was her association with the New English Art Club (NEAC). Founded in 1886 as an alternative to the more conservative Royal Academy, the NEAC became a vital platform for artists influenced by Impressionism and other modern French movements. Walker made history in 1900 when she became the first woman to be elected as a member of the NEAC. This was a considerable achievement, underscoring her talent and the respect she had garnered among her peers in a male-dominated institution.

Membership in the NEAC provided Walker with regular exhibition opportunities and placed her among the leading progressive artists of her day, including figures like Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer, and Augustus John. Her contributions to NEAC exhibitions helped solidify her reputation as a painter of note. She continued to exhibit widely, not only with the NEAC but also, in due course, at the Royal Academy itself, demonstrating her ability to bridge different art world factions. Her work was also selected for international showcases, including the prestigious Venice Biennale, further enhancing her standing.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Subject Matter

Ethel Walker's oeuvre is diverse, encompassing portraits, flower pieces, seascapes, and large-scale decorative compositions, often featuring nudes. Her style is generally characterized by a lyrical and often ethereal quality, a fluid brushwork, and a sophisticated sense of colour. While rooted in Impressionistic techniques, particularly in her handling of light and atmosphere, her work often transcends mere representation, imbuing her subjects with a poetic sensibility.

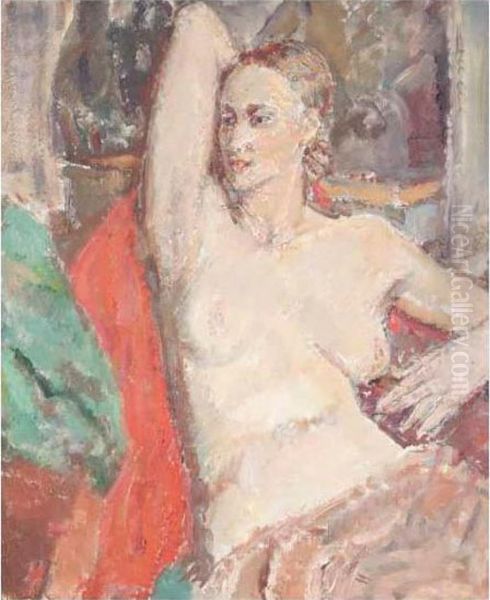

Portraits formed a significant part of her output. She was particularly adept at capturing the likeness and character of her sitters, often women, with a sympathetic and insightful approach. Her portraits are not just records of appearance but also explorations of personality and mood. She often employed a palette that, while vibrant, could also be subtle and harmonious, sometimes using a single dominant colour to unify a composition, especially in her depictions of female figures.

Her flower paintings are celebrated for their freshness and vitality, capturing the delicate beauty of blooms with a painterly touch. Seascapes, often inspired by her time spent at Robin Hood's Bay on the Yorkshire coast, where she maintained a cottage, convey the changing moods of the sea and sky with atmospheric depth. These works often show a more direct engagement with Impressionist principles, focusing on the effects of light on water and land.

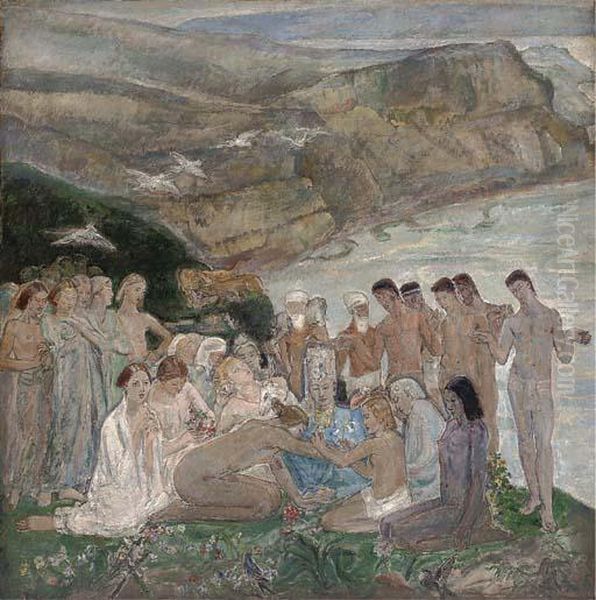

Perhaps her most ambitious and personal works are her decorative paintings, often large compositions featuring female nudes in idyllic, timeless settings. These pieces, sometimes referred to as "invocations" or "idylls," reflect her interest in classical themes, symbolism, and the creation of harmonious, dreamlike worlds. They showcase her skill in composition and her ability to evoke a sense of serenity and grace, drawing on her admiration for artists like Puvis de Chavannes and perhaps even the spirit of earlier masters.

Key Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Ethel Walker's artistic achievements. Among her most famous is "The Spanish Shawl," painted between 1921 and 1926. This striking portrait depicts Sylvia Hatton Thomas, enveloped in a richly patterned shawl. The work is notable for its bold composition, the vibrant colours of the shawl contrasting with the more subdued tones of the figure and background, and the sensitive portrayal of the sitter's contemplative expression. It exemplifies Walker's skill in portraiture and her ability to integrate decorative elements effectively.

Other notable portraits include "Miss Buchanan" and "Miss Jeanne Verneville de Laborie," both of which demonstrate her capacity to capture individual character with elegance and psychological insight. Her series of nudes, such as "Invocation," are significant for their lyrical quality and their exploration of the female form in harmonious, almost mythical, landscapes. These works often possess a mural-like quality, suggesting an ambition beyond easel painting.

Her seascapes, like "The Incoming Tide, Robin Hood's Bay," showcase her ability to capture the atmospheric conditions of the coast with a loose, expressive brushwork that conveys the movement of water and the quality of light. These paintings reveal a deep connection to the natural world and a keen observational skill, filtered through an Impressionistic lens.

Personal Life: Tragedy and Resilience

Ethel Walker's personal life was marked by a significant tragedy that undoubtedly cast a shadow. She married Ralph Ehrman, but the union was fraught with difficulty. In 1918, during a dispute, Ehrman shot Walker twice before taking his own life. This shocking event was a profound trauma. Walker survived the physical injuries, but the emotional and psychological impact must have been immense.

Despite this devastating experience, Walker demonstrated remarkable resilience, continuing to dedicate herself to her art. She never remarried and lived a relatively independent life, often dividing her time between her London studio in Chelsea and her cottage in Robin Hood's Bay. Her focus remained steadfastly on her painting, which perhaps served as both a passion and a solace.

Gender, Sexuality, and Artistic Identity

As a woman artist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ethel Walker faced the inherent challenges of a field largely dominated by men. Her election to the NEAC was a breakthrough, but the broader art world still presented obstacles for women seeking equal recognition. Walker, however, carved out a respected position through the sheer quality and consistency of her work.

There has been speculation regarding Walker's sexuality, with some art historians suggesting she may have been a lesbian. This interpretation is often supported by her frequent and sensitive portrayal of women, her focus on the female nude, and her independent lifestyle. In an era when open discussion of homosexuality was taboo, particularly for women, her art may have offered a space for exploring female beauty and connection in ways that were personal and meaningful to her. Her close friendships with women, and the intimate nature of some of her female portraits, lend credence to these interpretations, though definitive biographical evidence remains elusive.

Her work, particularly her nudes, sometimes caused controversy, as depictions of the female body by female artists often challenged conventional norms and expectations. However, she largely maintained a focus on aesthetic beauty and classical harmony rather than overt provocation. She was part of a generation of women artists, including figures like Laura Knight, Gwen John, Frances Hodgkins, and Vanessa Bell, who were asserting their presence and perspectives in the British art scene, each in their own distinct way. Dod Procter was another contemporary known for her striking portraits of women.

Recognition and Honours

Ethel Walker's contributions to British art did not go unrecognized during her lifetime. She exhibited regularly and her work was acquired by public collections, including the Tate Gallery. Her persistence and talent earned her significant accolades. In 1938, she was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), a further testament to her standing in the art establishment.

The crowning achievement of her career came in 1943 when she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE), a rare honour for a female artist at the time. This distinguished recognition placed her among a select group of women who had made exceptional contributions to British culture. She was one of the first women painters to receive this title, highlighting her pioneering role. Other prominent artists of her era who achieved widespread recognition included Sir William Orpen and the American-born but London-based John Singer Sargent, whose dazzling society portraits set a high bar.

Later Years and Legacy

Dame Ethel Walker continued to paint into her later years, remaining dedicated to her artistic vision. She passed away on March 2, 1951, in London, at the age of 89, leaving behind a substantial body of work. For a period after her death, like many artists of her generation whose style was not aligned with the dominant post-war movements like Abstract Expressionism, her reputation somewhat faded from mainstream art historical narratives.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in her work, partly due to a broader reassessment of early 20th-century British art and a greater focus on the contributions of women artists and figures who may have explored LGBTQ+ themes. Her paintings are now appreciated for their intrinsic beauty, their technical skill, and their unique blend of influences. She is recognized as an important transitional figure, bridging Victorian sensibilities with modern artistic approaches.

Her legacy lies in her distinctive artistic voice, her pioneering role as a woman in the British art world, and her creation of a body of work that celebrates beauty, femininity, and the natural world with a lyrical and often dreamlike quality. She stands alongside other significant British Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, such as Philip Wilson Steer and Walter Sickert, but with a vision that was uniquely her own. Her dedication to her craft, in the face of personal tragedy and societal constraints, remains an inspiring testament to the power of artistic commitment.

Conclusion

Dame Ethel Walker was more than just a painter; she was a quiet trailblazer. Her journey from the art schools of London to the esteemed halls of the Royal Academy and the New English Art Club, culminating in her damehood, charts a course of artistic dedication and achievement. Her ability to synthesize diverse influences – from French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to Asian art and classical traditions – into a coherent and personal style is remarkable. Her portraits, nudes, seascapes, and flower studies continue to resonate with their sensitivity, vibrant colour, and poetic atmosphere. As art history continues to broaden its scope and re-evaluate figures from the past, Dame Ethel Walker's contribution as a significant Scottish-born British artist, and a pioneering woman in her field, is rightly being given its due prominence.