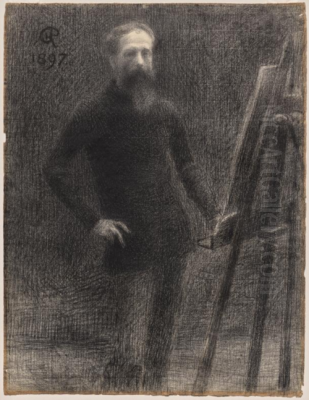

Hippolyte Petitjean (1854-1929) stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure within the vibrant landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A dedicated painter, he navigated the currents of artistic innovation, most notably aligning himself with the principles of Neo-Impressionism. Born in Mâcon, France, Petitjean's artistic journey took him from provincial training to the heart of the Parisian avant-garde, where he forged connections with leading artists and developed a distinctive style characterized by meticulous technique and a profound sensitivity to color and light.

Though his career was marked by periods of financial struggle, Petitjean remained committed to his craft, producing a body of work encompassing landscapes, figure studies, portraits, and decorative watercolors. He is primarily celebrated for his adoption and mastery of Pointillism, the technique pioneered by Georges Seurat, using small dots of pure color to create luminous and harmonious compositions. His life and work offer a fascinating insight into the evolution of Neo-Impressionism and the experiences of an artist dedicated to its ideals.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Mâcon and Paris

Hippolyte Petitjean's story begins in Mâcon, a town in the Burgundy region of France, where he was born in 1854. His formal education was brief; at the young age of 13, he left school to become an apprentice decorator. However, his artistic inclinations soon became apparent. Alongside his apprenticeship, he began taking drawing lessons at the local École de Dessin in Mâcon, laying the foundational skills for his future career.

His burgeoning talent did not go unnoticed. Petitjean secured a scholarship from the municipality of Mâcon, a crucial stepping stone that enabled him to pursue more advanced studies in the artistic capital, Paris. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art training in France. There, he entered the studio of Alexandre Cabanel, a highly respected and successful academic painter known for his historical, classical, and portrait subjects.

Studying under Cabanel provided Petitjean with rigorous training in drawing, composition, and traditional painting techniques. This academic grounding would remain subtly present even as he later embraced more radical, modern styles. His early works reflected this training, and he began exhibiting at the official Paris Salon, the Salon des Artistes Français, in 1880. He continued to show his work there regularly until 1891, initially presenting pieces that aligned more closely with academic expectations, possibly showing the influence of artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene, mural-like compositions with a Symbolist undertone.

The Call of the Avant-Garde: Embracing Neo-Impressionism

The mid-1880s marked a pivotal turning point in Petitjean's artistic development. Around 1884, he encountered the revolutionary work and ideas of Georges Seurat, the pioneering figure of Neo-Impressionism. Seurat, along with Paul Signac and others, was developing a new approach to painting based on scientific color theories, particularly those of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. This movement, often referred to as Pointillism or Divisionism, sought to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy by applying small, distinct dots or "points" of pure color to the canvas.

The theory was that these juxtaposed dots would mix optically in the viewer's eye, creating a more brilliant and harmonious effect than colors physically mixed on the palette. Petitjean was deeply impressed by this systematic and rational approach to color and light, which stood in stark contrast to the more intuitive methods of the Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He became a convert to the Neo-Impressionist cause.

By 1886, Petitjean had befriended Seurat and Signac and began experimenting with the Pointillist technique himself. He became associated with the group of artists championing this new style. In 1891, he began exhibiting regularly at the Salon des Indépendants, an alternative exhibition venue founded by artists including Seurat, Signac, Albert Dubois-Pillet, and Odilon Redon, which welcomed avant-garde art rejected by the official Salon. Petitjean became recognized as one of the key figures among the first generation of Neo-Impressionist painters.

Mastering the Dot: Petitjean's Pointillist Vision

Petitjean fully embraced the demanding technique of Pointillism, meticulously applying small dots of color to build his compositions. His work from this period demonstrates a deep understanding of color theory and a patient dedication to the method. Unlike the often-spontaneous brushwork of Impressionism, Petitjean's Pointillism required careful planning and precise execution. The goal was to create a surface that shimmered with light and color, achieving a sense of harmony and order.

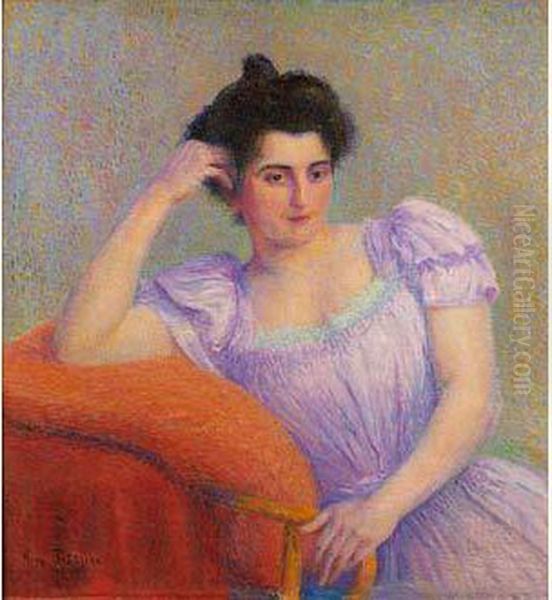

His subjects during his main Pointillist phase often included tranquil landscapes, capturing the subtle effects of light on water and foliage. He frequently depicted scenes along the Seine or in the French countryside, imbuing them with a sense of timeless serenity. Figure studies were also important, particularly his depictions of bathers. These works, such as his well-known Les Baigneuses (Bathers), connected with classical themes of the nude in nature, previously explored by artists from Titian to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, but rendered them through the distinctly modern lens of Neo-Impressionism.

An early example of his Pointillist work is Sous-bois (Undergrowth), painted between 1890 and 1894. This piece likely showcases his exploration of light filtering through trees, using dots of varying color to represent foliage, shadow, and dappled sunlight. His application of the technique aimed not just for optical vibrancy but also for a sense of rhythm and decorative pattern across the canvas, reflecting a careful compositional structure.

Exhibiting the New Vision: Salons and Galleries

Petitjean actively sought venues to display his evolving work. His participation in exhibitions charts his journey from academic circles to the forefront of the avant-garde. After his initial decade exhibiting at the official Paris Salon (1880-1891), his allegiance shifted decisively towards independent venues that supported modern art.

The Salon des Indépendants became his primary platform in Paris from 1891 onwards. Exhibiting alongside fellow Neo-Impressionists like Seurat (until his untimely death in 1891), Signac, Camille Pissarro (who briefly adopted the style), Maximilien Luce, and Henri-Edmond Cross, Petitjean solidified his position within the movement. These exhibitions were crucial for disseminating Neo-Impressionist ideas and challenging established artistic norms.

Petitjean's reputation also extended beyond Paris. He was invited to exhibit with Les XX (Les Vingt), a highly influential avant-garde group based in Brussels, Belgium. He participated in their exhibitions in 1892 and 1893 (some sources also suggest 1887), placing his work alongside leading international modern artists. This participation underscores his recognition within progressive European art circles.

He also had solo or featured presentations in commercial galleries known for promoting new art. In 1902, he exhibited at the Galerie Le Barc de Boutteville in Paris, a gallery noted for its support of Symbolist and Post-Impressionist artists. He also showed work at the Galerie Moline (1894) and the Galerie des Beaux-Arts (1902) in Paris. Furthermore, his work was shown internationally, with exhibitions recorded in Berlin (1903), Vienna (1905), and Bonn (1921), demonstrating a continued, albeit perhaps modest, international presence throughout his later career.

Navigating Artistic Currents: Style Evolution and Watercolors

While deeply committed to Neo-Impressionism, Petitjean's artistic path was not entirely linear. Around the mid-to-late 1890s, following Seurat's death and perhaps seeking new expressive possibilities, he temporarily moved away from a strict adherence to the Pointillist technique in his oil paintings. During this period, his work sometimes showed a renewed connection to the Symbolist aesthetics of artists like Puvis de Chavannes, focusing on more allegorical themes and potentially employing broader areas of color or softer forms.

It was also during this time, and increasingly in the early 20th century, that Petitjean devoted significant attention to watercolor. He developed a distinctive approach to this medium, often combining the principles of Divisionism with the inherent fluidity and transparency of watercolor. He created numerous landscapes and decorative compositions using dots or small strokes of pure watercolor.

Around 1910, Petitjean experienced a resurgence of interest in Pointillism, returning to the technique with renewed vigor, particularly in his watercolors. These later works often possess a remarkable luminosity and a decorative quality. He focused on capturing the essence of landscapes – harbors, riversides, parks – simplifying forms while emphasizing the harmonious interplay of color and light. This later phase demonstrates his enduring belief in the expressive potential of divided color, adapted to the unique properties of watercolor.

Life's Realities: Teaching and Perseverance

Despite his artistic dedication and participation in significant exhibitions, Hippolyte Petitjean's life was often marked by financial instability. The avant-garde art market was precarious, and Neo-Impressionism, while influential, did not always translate into commercial success for all its practitioners, especially compared to some of the more established Impressionists.

Biographical details suggest personal hardships as well. His father passed away when Petitjean was only 19. Later in life, he lived in modest circumstances, residing in a small apartment in the southern part of Paris with his daughter. To support himself and his family, Petitjean relied heavily on teaching. He worked as a drawing instructor, a common recourse for many artists struggling to make a living solely from their art sales.

This need to teach, while providing necessary income, inevitably consumed time and energy that might otherwise have been devoted to his painting. Nevertheless, Petitjean persevered. He continued to create art throughout his life, adapting his style and exploring different mediums while remaining fundamentally connected to the principles of color harmony and light that had first drawn him to Neo-Impressionism. His resilience in the face of economic challenges speaks to his deep commitment to his artistic vision.

Signature Works: A Closer Look

Several key works exemplify Hippolyte Petitjean's artistic achievements and stylistic range:

Les Baigneuses (Bathers): This subject, revisited by Petitjean, is perhaps his most iconic. These compositions often feature female nudes in idyllic landscape settings, rendered in the Pointillist technique. They blend a classical, arcadian theme with a modern, scientific approach to color. The meticulous dots create a vibrant tapestry of light and reflection, particularly on skin and water, achieving a serene yet shimmering effect. These works invite comparison with similar subjects by Seurat (Bathers at Asnières, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte) and Impressionists like Renoir, highlighting Neo-Impressionism's distinct emphasis on structure and optical science.

Le Pont Neuf (The New Bridge): Painted later in his career (circa 1912-1914), this work depicts one of Paris's most famous bridges. It showcases Petitjean's mature Pointillist style, possibly applied with slightly larger dots or strokes, characteristic of some later Neo-Impressionist developments. The painting captures the atmosphere of the city and the play of light on the Seine and surrounding architecture. It stands as a testament to his enduring engagement with the technique and contrasts with the more fleeting, atmospheric depictions of Paris by Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro.

Le Déjeuner (The Luncheon): This work likely portrays an outdoor meal or picnic scene, a theme popular among Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters celebrating modern leisure. Petitjean would have approached this subject with his characteristic Pointillist precision, focusing on the effects of sunlight filtering through leaves, the bright colors of clothing and food, and the overall harmony of the composition. It reflects the Neo-Impressionist interest in contemporary life, rendered through their specific optical methods.

Other notable works mentioned include Sous-bois (Undergrowth), capturing woodland light; Madame Marthe, a portrait whose restoration was funded by the MACON association; Baigneuse au bord de l'eau (Bather by the Water), which achieved a respectable price at auction; La Sympathie, donated to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; and Tête (Head), a work donated by his family to the museum in Lyon. Together, these works illustrate his range from landscape and genre scenes to portraiture, all explored through his unique Neo-Impressionist lens.

A Network of Artists: Contemporaries and Influences

Hippolyte Petitjean did not work in isolation. He was part of a dynamic network of artists in Paris and beyond, influencing and being influenced by his contemporaries.

His most crucial connections were within the Neo-Impressionist circle:

Georges Seurat: The founder of the movement and Petitjean's primary inspiration. Seurat's systematic approach and iconic works like La Grande Jatte provided the model Petitjean initially followed.

Paul Signac: A close friend and fellow advocate of Neo-Impressionism, Signac became the movement's leading theorist and promoter after Seurat's death, continuing to champion Divisionism throughout his long career.

Camille Pissarro: The elder Impressionist statesman briefly adopted the Pointillist technique in the mid-1880s, exhibiting alongside Seurat and Signac, though he later returned to a freer style. His temporary adherence lent credibility to the young movement.

Henri-Edmond Cross (formerly Delacroix): Another key Neo-Impressionist, known for his vibrant depictions of the South of France, often using slightly larger, mosaic-like touches of color in his later work.

Maximilien Luce: A Neo-Impressionist with strong anarchist sympathies, Luce often depicted urban and industrial scenes alongside landscapes, using a vigorous Pointillist technique.

Albert Dubois-Pillet: An early member of the group and co-founder of the Salon des Indépendants, known for his cityscapes and river views.

Beyond the core group, Petitjean's work shows awareness of other artistic currents:

Alexandre Cabanel: His teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts, representing the academic tradition Petitjean moved away from, but whose rigorous training likely informed his draftsmanship.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: A major figure associated with Symbolism, whose calm, ordered, and often allegorical compositions influenced many artists, including Petitjean, particularly in his figure subjects and perhaps during his temporary departure from strict Pointillism.

Petitjean's work can also be understood in the broader context of Post-Impressionism, alongside artists who, like the Neo-Impressionists, sought new directions beyond Impressionism:

Vincent van Gogh: Explored color for emotional expression using distinct, energetic brushstrokes, a contrast to Pointillism's systematic approach.

Paul Gauguin: Moved towards Symbolism and Synthetism, using flat areas of bold color and simplified forms, differing significantly from Neo-Impressionism's optical goals.

Compared to Impressionists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, Petitjean's work emphasized structure, scientific theory, and permanence over capturing fleeting moments.

Legacy and Rediscovery

During his lifetime, particularly in his later years, Hippolyte Petitjean did not achieve the same level of fame or financial success as some of his Neo-Impressionist peers like Signac. His adherence to Pointillism, even after it had passed its peak of avant-garde novelty, and his quiet life dedicated partly to teaching, meant he was somewhat overshadowed.

However, his contribution was not forgotten. Posthumous recognition began to build momentum in the mid-20th century. A significant memorial exhibition was held at the Institut Néerlandais in Paris in 1955, helping to reintroduce his work to a wider audience. More recently, a major retrospective exhibition titled "Hippolyte Petitjean (1854–1929). Pointillism and Watercolour" was organized by the Musée des Ursulines in his hometown of Mâcon in 2015. This exhibition featured 117 works and significantly contributed to the reassessment of his career, particularly highlighting his mastery of watercolor within the Neo-Impressionist framework.

Petitjean's works are now held in various public and private collections. The donation of La Sympathie by collector B. Gerald Cantor to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the donation of Tête by his family to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, exemplify how his art has entered institutional holdings. The support from organizations like the MACON association for the restoration of Madame Marthe also indicates local and institutional appreciation.

His paintings and watercolors appear on the art market, with works like Baigneuse au bord de l'eau achieving notable prices at auction. Collectors such as Samuel Josefowitz and Gaston Bachelard have owned his pieces, indicating a consistent, if sometimes niche, interest among connoisseurs of the period. This gradual rediscovery ensures that Hippolyte Petitjean's unique voice within Neo-Impressionism continues to be heard.

Conclusion: A Distinctive Voice in Neo-Impressionism

Hippolyte Petitjean represents a fascinating strand within the complex tapestry of Neo-Impressionism. Deeply influenced by Georges Seurat, he dedicated much of his career to exploring the possibilities of Pointillism, creating works characterized by their luminous color, harmonious compositions, and meticulous technique. While facing the economic hardships common to many artists of his time, he persevered, producing a significant body of work across oil and watercolor.

His journey from academic training under Cabanel to embracing the avant-garde theories of Seurat and Signac, his participation in key exhibitions like the Salon des Indépendants and Les XX, and his later focus on decorative watercolors all paint a picture of an artist committed to his chosen path. Though perhaps less revolutionary than Seurat or as prolific a promoter as Signac, Petitjean developed a distinctive style, particularly evident in his serene landscapes and idealized figure studies.

Through posthumous exhibitions and continued scholarly interest, Hippolyte Petitjean's contribution to French art is increasingly recognized. He stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of Neo-Impressionism's quest for harmony and light, a master of the dot whose works continue to resonate with quiet beauty and technical brilliance. His life and art enrich our understanding of the diverse expressions found within the Post-Impressionist era.