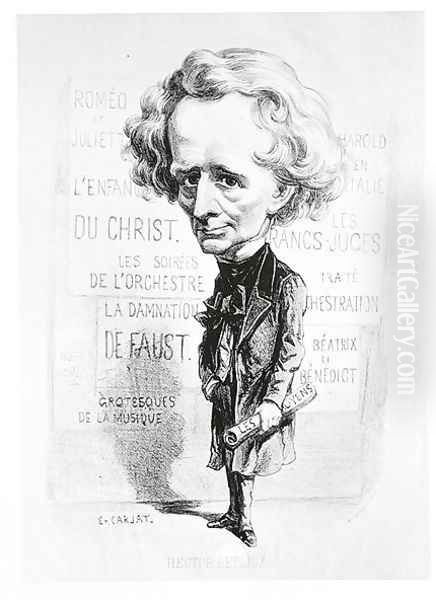

Étienne Carjat (1828-1906) stands as a pivotal yet sometimes underappreciated figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art and letters. A man of diverse talents, he navigated the bustling Parisian world as a journalist, a biting caricaturist, and, most enduringly, a photographer of remarkable insight and sensitivity. His portraits, particularly of the era's leading artists, writers, and thinkers, offer an invaluable window into the intellectual and creative ferment of his time. More than mere likenesses, Carjat’s photographs sought to capture the essence, the "inner spirit," of his sitters, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of figures who shaped modern culture.

Early Life and Foray into Caricature

Born Étienne Carjat on March 28, 1828, in Fareins, Ain, France, his early inclinations were towards the literary and visual arts, though not immediately photography. Like his slightly older contemporary, Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, better known as Nadar, Carjat initially made his mark in the world of Parisian journalism and caricature. This was a vibrant and often politically charged field, where sharp wit and a keen eye for human folly were essential tools. Caricature, in 19th-century France, was not merely light entertainment; it was a powerful medium for social and political commentary, capable of shaping public opinion and challenging authority.

Carjat's talent for caricature found an outlet in various satirical publications. He was instrumental in founding Le Diogène in 1856, a journal named after the ancient Greek cynic philosopher, Diogenes of Sinope, suggesting its critical and perhaps iconoclastic stance. His drawings, often characterized by their incisive lines and exaggerated yet recognizable features, lampooned public figures and commented on the mores of the day. This early work honed his observational skills and his ability to distill a personality into a few telling strokes – a skill that would later prove invaluable in his photographic portraiture. His involvement with publications like Goutois further showcased his satirical bent, reflecting the societal undercurrents and the often-turbulent political landscape of France during the Second Empire and the early Third Republic.

His experience as a caricaturist instilled in him a profound understanding of facial physiognomy and the subtle ways in which character is expressed. Unlike some portraitists who sought to idealize their subjects, Carjat, perhaps influenced by the realist tendencies of artists like Honoré Daumier – a master caricaturist and painter whom Carjat knew and collaborated with – was more interested in capturing an unvarnished truth, a psychological depth.

The Transition to Photography: A New Medium for a New Age

The mid-19th century witnessed the burgeoning field of photography, a revolutionary technology that was rapidly transforming how people saw the world and themselves. Initially viewed by some in the traditional art establishment with skepticism, photography quickly gained popularity for its perceived objectivity and its ability to capture a fleeting moment with unprecedented accuracy. Paris, as a cultural and scientific hub, was at the forefront of photographic innovation. Figures like Louis Daguerre had laid the groundwork, and a new generation of practitioners was exploring the artistic potential of the medium.

It was in this exciting environment that Carjat, around 1858 or 1860, turned his attention to photography, establishing his own portrait studio at 56 Rue Laffitte in Paris. This street was already becoming a notable address for photographers and art dealers, placing him in the heart of the artistic commerce of the city. His decision to embrace photography was not an abandonment of his earlier pursuits but rather an expansion of his artistic toolkit. The camera offered a different, perhaps more direct, means of engaging with the human subject.

His contemporary, Nadar, had already established a highly successful photographic studio, attracting a glittering clientele of celebrities. While Carjat and Nadar were in some ways competitors, they also shared a common background in caricature and a deep engagement with the Parisian bohemian and intellectual circles. Their approaches to portraiture, while distinct, both emphasized capturing the personality of the sitter over mere superficial likeness. Both men understood that a great portrait was a collaboration, a dialogue between photographer and subject.

Carjat’s studio quickly became a meeting place for the artistic and literary avant-garde. His background as a journalist and caricaturist had already provided him with a wide network of contacts, and his engaging personality undoubtedly helped attract a diverse clientele. He was not just a technician behind the camera; he was a participant in the cultural life he documented.

The Carjat Portrait: Style and Substance

Étienne Carjat’s photographic style is often characterized by its directness, its psychological acuity, and its relative lack of artifice. He generally preferred simple backgrounds and natural poses, allowing the sitter's face and demeanor to take center stage. This approach contrasted with some contemporary photographers who favored elaborate props, painted backdrops, and highly theatrical staging. Carjat's interest lay in the individual, in the unique spark of personality that could be revealed through the lens.

He was a master of lighting, often using it to sculpt the features of his subjects, highlighting their character without resorting to overly dramatic effects. His compositions were carefully considered, frequently focusing on the head and shoulders or a three-quarter length view, a common practice that concentrated attention on the face. The cropping, sometimes to below the knee, ensured that the viewer's gaze was drawn inexorably to the sitter's expression and eyes, which Carjat clearly saw as windows to the soul.

One of the hallmarks of Carjat's portraiture was his ability to put his subjects at ease, encouraging a naturalness that was not always easy to achieve with the long exposure times required by early photographic processes. His sitters often appear thoughtful, engaged, or imbued with a quiet intensity, rather than stiffly posed or self-conscious. This "naturalism," as it was described in the provided text, was a conscious choice, aiming to capture the individual as they were, not as they might wish to be presented in an idealized fashion. This approach aligned with the broader Realist movement in painting, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet, who was also a subject of Carjat's lens.

The technical aspects of his work involved the prevailing methods of the time, likely including the wet collodion process for negatives and albumen prints. The mention of "Gelatin silver print" in the provided material points to a later printing process that became dominant towards the end of the 19th century, suggesting Carjat adapted his techniques over his long career. Regardless of the specific chemical processes, his prints were known for their rich tonal range and clarity, effectively conveying the textures of skin and fabric, and the subtle play of light and shadow.

Capturing the Luminaries: A Pantheon of Parisian Intellectuals

Carjat’s studio became a veritable who's who of 19th-century Parisian cultural life. His most famous and frequently reproduced portraits are those of the poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire, images that have become iconic representations of these complex literary figures.

The portrait of a young Arthur Rimbaud, taken in October 1871, is perhaps Carjat's single most famous photograph. It shows the teenage poet with a somewhat unruly shock of hair, an intense, almost defiant gaze, and a hint of vulnerability. This image, often referred to as "L'homme aux semelles de vent" (the man with soles of wind), has profoundly shaped our visual conception of the precocious and rebellious poet. It captures the raw energy and intellectual fire that characterized Rimbaud's brief but explosive literary career. The story goes that Paul Verlaine, Rimbaud's lover and fellow poet, brought him to Carjat's studio.

Charles Baudelaire, the tormented poet of modernity and author of Les Fleurs du mal, was another significant subject for Carjat. He photographed Baudelaire on several occasions, and these portraits, like those by Nadar, convey the poet's dandyism, his intellectual intensity, and his underlying melancholy. Baudelaire himself had a complex relationship with photography, famously critiquing its potential to supplant "true art" in his Salon review of 1859, yet he sat for numerous photographic portraits. Carjat’s images of Baudelaire are less theatrical than some of Nadar's, often presenting a more direct and unadorned confrontation with the poet's piercing gaze. These portraits were later included in the Galerie Contemporaine, Littéraire, Artistique, a prestigious series of photographic portraits of celebrities published by Goupil & Cie, underscoring their perceived importance.

Beyond these two literary giants, Carjat’s lens captured a wide array of other influential figures. He photographed the novelist Émile Zola, a leading proponent of Naturalism in literature, whose powerful and often controversial works explored the social realities of 19th-century France. Carjat's portraits of Zola convey a sense of gravitas and intellectual rigor.

The world of visual arts was also well-represented in Carjat's portfolio. He photographed the aforementioned Gustave Courbet, the provocative leader of the Realist school of painting. A letter from Courbet to Carjat exists, requesting him to photograph his friend Victor Frondes, indicating a professional and perhaps personal relationship. He also photographed Honoré Daumier, whose satirical prints and paintings offered a scathing critique of bourgeois society and political corruption. Other artists who likely crossed paths with Carjat or sat for him, given his central position in the Parisian art world, include painters like Édouard Manet, whose work often scandalized the official Salon, and Henri Fantin-Latour, known for his group portraits of artists and writers, such as "A Studio at Les Batignolles" which depicted Manet and his circle, including Zola. While direct photographic evidence for all these figures by Carjat might be elusive for some, his studio was a known hub.

Musicians, politicians, and other public figures also frequented Carjat's studio. He photographed the composer Gioachino Rossini, the statesman Léon Gambetta, who played a crucial role in the founding of the Third Republic, and the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (referred to as Emile Carpeaux in the source, likely a slight misnomer). These portraits demonstrate the breadth of Carjat's connections and his role as a chronicler of his era's prominent personalities. Other figures from the literary and artistic milieu who were active and likely photographed by either Carjat or his contemporaries like Nadar include Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas (père and fils), George Sand, Théophile Gautier, and the influential art critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. The actress Sarah Bernhardt, a global superstar, was a frequent subject for Nadar, and it's plausible Carjat also photographed her or figures from her theatrical world.

Le Boulevard and Continued Journalistic Endeavors

Despite his growing success as a photographer, Carjat did not entirely abandon his journalistic roots. In 1861, he co-founded the journal Le Boulevard with the writer Henri Aubert and with contributions from Honoré Daumier. This publication aimed to be a sophisticated weekly, blending literature, art criticism, satirical commentary, and illustrations. It provided a platform for many writers and artists, reflecting Carjat's continued engagement with the broader cultural discourse of Paris.

Le Boulevard featured literary contributions from figures like Baudelaire and Théodore de Banville, and its illustrations often included caricatures and drawings by prominent artists. Carjat's role in such a publication highlights his multifaceted talents and his desire to foster a space where different artistic and literary forms could intersect. The journal, though relatively short-lived (it ceased publication in 1863), was indicative of the vibrant intellectual climate of the period and Carjat's active participation within it. His involvement in such ventures demonstrates that he saw photography, caricature, and journalism not as separate silos, but as interconnected means of observing, interpreting, and commenting on the world around him.

Political Engagement and Personal Challenges

Carjat's life was not solely confined to the studio and editorial offices. He was a man of his times, and the political upheavals of 19th-century France inevitably touched his life. The provided information notes his involvement as a lieutenant in the National Guard during the 1848 Revolution. This period of widespread European unrest saw the overthrow of King Louis Philippe I and the establishment of the French Second Republic. His participation suggests republican sympathies and a willingness to engage directly in the political struggles of his era. This political consciousness likely informed his satirical work and perhaps even his approach to portraiture, which often sought to reveal the unvarnished character of his subjects, regardless of their social standing.

Like many artists, Carjat also faced personal and financial challenges. The 1860s, despite his growing reputation, reportedly brought economic difficulties, at one point forcing him to relinquish a lease. However, he persevered, and his photographic practice continued to thrive, producing thousands of portraits over his career. This resilience in the face of adversity speaks to his dedication to his craft and his entrepreneurial spirit. The business of photography, while potentially lucrative, was also competitive, and maintaining a successful studio required not only artistic talent but also business acumen.

Friendships and Rivalries: The Case of Nadar

The relationship between Étienne Carjat and Nadar is particularly noteworthy. Both men were towering figures in early French photography, and their careers ran parallel in many respects. Both started as caricaturists, possessed bohemian sensibilities, and moved in similar artistic and literary circles. They photographed many of the same celebrated individuals, including Baudelaire, Sarah Bernhardt, and Gustave Doré (the prolific illustrator).

While they were undoubtedly competitors, their relationship appears to have been complex, possibly encompassing elements of mutual respect and perhaps professional rivalry. Nadar, with his flamboyant personality, his famous red-accented studio, and his daring exploits like aerial photography from a hot air balloon, often cast a larger shadow in popular accounts of the period. However, Carjat’s work, often quieter and more introspective, holds its own in terms of artistic merit and psychological depth.

Comparisons are often drawn between their respective portraits of the same individuals. For instance, Nadar’s portraits of Baudelaire are perhaps more dramatic and overtly romantic, while Carjat’s tend towards a more stark and direct realism. Both, however, succeeded in creating powerful and enduring images. The "interaction" with Félix Nadar and the painter Charles Breton (perhaps Jules Breton, a notable painter of rural life, or another contemporary) mentioned in the source material suggests a network of professional and personal connections that characterized the Parisian art scene. These artists did not work in isolation; they were part of a dynamic community that exchanged ideas, collaborated, and sometimes competed.

Artistic Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Étienne Carjat’s contribution to the art of photography, particularly portraiture, is significant and enduring. He was a pioneer who understood the unique potential of the camera to capture not just a physical likeness but also the intangible qualities of personality and intellect. His ability to create portraits that feel both immediate and timeless is a testament to his skill and artistic vision.

His work is valued for its historical importance, providing a visual record of many key figures of 19th-century French culture. For scholars studying Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Zola, or Courbet, Carjat’s photographs are indispensable primary sources, offering insights that textual descriptions alone cannot provide. His portraits have been widely reproduced and are held in the collections of major museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, which houses an extensive collection of 19th-century French art and photography.

While perhaps not always afforded the same level of popular recognition as Nadar during certain periods, Carjat's reputation has steadily grown, and art historians today recognize him as one of the foremost portrait photographers of his era. His influence can be seen in the work of later photographers who continued to explore the psychological dimensions of portraiture. He demonstrated that photography could be a powerful art form, capable of profound human expression, at a time when its artistic status was still being debated.

His commitment to a form of naturalism or realism in his portraits, focusing on the character of the sitter without excessive flattery or artificiality, aligned with broader artistic currents of his time, particularly the Realist movement in painting led by figures like Courbet and Jean-François Millet. However, his subjects also included Symbolist poets like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, suggesting his appeal transcended specific artistic schools. He was, above all, interested in the individual.

The sheer volume of his output, numbering in the thousands of portraits, also speaks to his industriousness and the demand for his work. He successfully navigated the commercial aspects of photography while maintaining a high artistic standard. His involvement in publications like Le Boulevard and Le Diogène further cements his place as an active and influential participant in the cultural life of his time, a man who used both the pen and the lens to engage with the world around him.

Conclusion: The Enduring Gaze of Étienne Carjat

Étienne Carjat passed away in Paris on March 8 or 9, 1906. He left behind a rich legacy of images that continue to fascinate and inform. As a caricaturist, he sharpened his eye for human character. As a journalist and editor, he engaged with the intellectual currents of his day. But it is as a photographer that his most lasting contribution was made. His portraits of the artists, writers, and thinkers who defined 19th-century Paris are more than historical documents; they are profound works of art that capture the spirit of an age and the enduring complexities of the human face.

In an era of rapid technological change and artistic innovation, Carjat embraced the new medium of photography and used it to create a unique and invaluable record of his contemporaries. His ability to look beyond the surface, to capture the "inner spirit" that the provided text so aptly describes, ensures his place among the masters of photographic portraiture. His work invites us to look closely, to engage with the personalities he depicted, and to appreciate the subtle art of a photographer who truly understood the power of the human gaze, both his own and that of his sitters. The legacy of Étienne Carjat is a testament to the enduring power of the portrait to connect us across time to the individuals who shaped our cultural heritage.