Carl Everton Moon, a significant figure in early 20th-century American photography, dedicated much of his career to documenting the lives, cultures, and landscapes of Native American peoples in the Southwestern United States. His work, while sometimes viewed through the lens of its era's romanticism, provides an invaluable visual record of communities undergoing profound change. Moon was not merely a photographer; he was an artist, an illustrator, and a storyteller, whose images and writings sought to capture the spirit and dignity of his subjects.

Early Life and a New Beginning in the Southwest

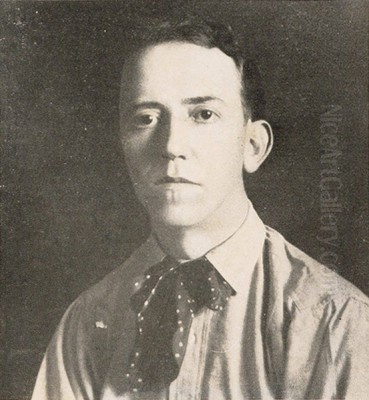

Born Karl Everton Moon on October 5, 1879, in Wilmington, Ohio, his early life set the stage for a path less traveled. After graduating from Wilmington High School in 1899, a pivotal decision led him westward. Around 1903, he arrived in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a region then still perceived by many in the Eastern United States as a frontier. It was here, amidst the vibrant cultures and dramatic landscapes, that Moon established his first photographic studio. This move marked the true beginning of his lifelong engagement with the indigenous peoples of the region.

The Southwest at the turn of the century was a crucible of cultural interaction and transformation. The expansion of railways, like the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, was opening up the region to increased settlement, tourism, and commercial enterprise. For artists and ethnographers, it was also a place of immense interest, seen as a repository of ancient traditions and "unspoiled" cultures. Moon stepped into this dynamic environment, equipped with his camera and a burgeoning desire to document what he saw.

The Photographer's Gaze: Documenting Indigenous Cultures

Carl Moon's photographic endeavors quickly centered on the Native American tribes of the Southwest. He developed working relationships with various communities, including the Navajo (Diné), the numerous Pueblo groups (such as those at Acoma, Laguna, and various Rio Grande pueblos), the Hopi, and the Apache. His access allowed him to create a rich tapestry of images depicting daily life, ceremonial practices, individual portraits, and the stunning natural environment that shaped these cultures.

His photographs aimed to capture more than mere ethnographic data; Moon sought an artistic and often empathetic portrayal. He was interested in the human element, the dignity of individuals, and the aesthetic qualities of their attire, crafts, and surroundings. This approach placed him within a broader movement of artists and photographers who were drawn to Native American subjects, a group that included figures like Edward S. Curtis, whose monumental project "The North American Indian" was contemporaneous with Moon's most active period.

Moon's images often reflect the pictorialist sensibilities prevalent in photography at the time. Pictorialism emphasized beauty, composition, and emotional impact, often through soft focus, manipulated prints, and carefully staged scenes. While this pursuit of an aesthetic ideal sometimes led to romanticized or idealized portrayals, it also resulted in photographs of considerable artistic merit. He worked with various photographic processes, including platinum prints, which were prized for their rich tonal range and archival permanence, evident in collections like his "He Last of His People."

Commercial Ventures and Wider Audiences: The Fred Harvey Era

A significant chapter in Moon's career began in 1907 when he joined the Fred Harvey Company. Fred Harvey was a visionary entrepreneur whose company operated a chain of restaurants, hotels (often called "Harvey Houses"), and retail shops along the Santa Fe Railway. The company played a crucial role in promoting tourism to the Southwest and in popularizing Native American arts and crafts.

Moon was hired to produce photographs of Native Americans and Southwestern scenes for the company. These images were widely disseminated through postcards, promotional brochures, illustrated books, and as part of the "Fred Harvey Collection of Southwest Indian Pictures." This work brought Moon's photography to a vast public audience, shaping popular perceptions of Native American life and the Southwestern landscape. His images became iconic, contributing to the romantic allure of the region.

During his tenure with Fred Harvey, which lasted until around 1914, Moon traveled extensively. His role sometimes overlapped with that of other artists employed or patronized by the company, which understood the power of visual culture in marketing the "Indian Detours" and the exoticism of the Southwest. Artists like Louis Akin, who also depicted Southwestern scenes and Native peoples, were part of this broader cultural production. Moon also served for a time as an official photographer for the Santa Fe Railroad itself, further cementing his connection to the forces shaping the modern West.

Artistic Collaborations and Influences

Moon's time in the Southwest was not spent in artistic isolation. He interacted with and learned from visiting artists. Among those he reportedly studied with or alongside were painters like Thomas Moran, whose grand, romantic landscapes of the American West had already achieved national fame. Moran's influence, particularly his emphasis on the sublime beauty of the landscape, can be subtly felt in some of Moon's scenic compositions.

Other artists active in the region, such as Frank Sauerwein and the aforementioned Louis Akin, also contributed to the artistic milieu of the early 20th-century Southwest. The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915, included painters like E. Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp, Oscar E. Berninghaus, W. Herbert Dunton, Ernest L. Blumenschein, and Bert Geer Phillips. While Moon was primarily a photographer, the concerns of these painters – capturing the unique light, culture, and atmosphere of New Mexico – paralleled his own. They were all, in their respective media, contributing to a burgeoning regional artistic identity.

Moon's artistic network extended beyond the Southwest. He is known to have met Charles M. Russell, the famed "cowboy artist," in New York. Russell, known for his dynamic portrayals of Western life, reportedly painted a portrait of Moon, indicating a mutual respect between the two artists working to define the visual narrative of the American West. Another contemporary, Frederic Remington, though more focused on action and the disappearing frontier, also contributed to the popular imagery of the West that formed the backdrop to Moon's work.

In Albuquerque, Moon also entered into a business partnership with Thomas F. Keleher, forming the Moon-Keleher Studio. This collaboration likely facilitated the commercial aspects of his photographic practice before his engagement with the Fred Harvey Company.

A Creative Partnership: Carl and Grace Moon

In 1914, Carl Moon married Grace Purdie, an accomplished writer and artist in her own right. This union marked the beginning of a fruitful creative partnership. Together, Carl and Grace Moon co-authored and illustrated numerous children's books centered on Native American themes and characters. Titles such as "The Yellow Dog and the Smart Hen" (though this specific title might be a slight variation or a lesser-known work, their collaborative bibliography is extensive), "Lost Indian Magic," "Chi-Weé," and "The Flaming Arrow" (likely a reference to "The Arrow of Fire" or similar titles) brought stories inspired by Native American cultures to a young audience.

Carl often provided the illustrations, drawing upon his deep familiarity with Native American life, attire, and customs. Grace's narratives, while products of their time, generally aimed to present sympathetic and engaging portrayals of Native American children and their worlds. These books, popular in their day, played a role in shaping children's understanding of indigenous cultures, offering alternatives to more stereotypical or negative depictions. Their collaborative efforts extended Moon's reach beyond photography and into the realm of literature and illustration, further disseminating his vision.

Notable Works and Artistic Style

Carl Moon's body of work is extensive. Beyond the images created for the Fred Harvey Company, his personal projects resulted in powerful individual portraits and thematic series. His platinum print portfolio, "He Last of His People," suggests a concern with the "vanishing race" trope common in that era, a narrative also strongly associated with Edward S. Curtis. This perspective, while reflecting a prevalent anxiety about the future of Native cultures in the face of assimilationist pressures, also imbued his subjects with a sense of nobility and tragic grandeur.

Photographs like "Little Maid of the Desert" exemplify his romantic and often sentimental approach. These works were carefully composed, with attention to lighting, pose, and costume, aiming for an aesthetic effect that transcended mere documentation. His style blended elements of realism, in the faithful depiction of ethnographic details, with a romanticism that sought to evoke emotion and idealize his subjects. This approach was not unique to Moon; photographers like Adam Clark Vroman, active in the Southwest slightly earlier and contemporaneously, also balanced documentary intent with aesthetic considerations, though often with a more straightforward, less overtly romantic style.

Moon's skill extended to capturing the vastness and unique quality of the Southwestern landscape, which often served as a dramatic backdrop to his portraits or as subjects in their own right. His understanding of light and composition allowed him to convey the stark beauty and spiritual resonance of places like the Grand Canyon or the desert mesas.

Controversies and Critical Perspectives

Like many artists of his time who depicted Native American subjects, Carl Moon's work is not without its complexities and has been subject to critical re-evaluation. One area of discussion revolves around the romanticization and sentimentalization present in some of his images. Critics argue that such portrayals, while perhaps well-intentioned, could contribute to a stereotypical or overly idealized view of Native American life, potentially obscuring the harsh realities of colonization, poverty, and cultural loss that many communities faced. Titles like "Last of His People" can be seen as perpetuating the "vanishing Indian" myth, which conveniently ignored the resilience and continued existence of Native nations.

The issue of staging in his photographs is another point of consideration. It was common practice for photographers of that era, including Moon and Curtis, to pose subjects, select specific attire (sometimes anachronistic), and arrange scenes to achieve a desired aesthetic or narrative effect. While this was often done to create a "timeless" or "authentic" image, it raises questions about the absolute documentary truthfulness of such photographs. Evidence suggests that some of Moon's photographs, even those predating his Fred Harvey employment, involved a degree of staging.

Furthermore, his commercial work for the Fred Harvey Company and the Santa Fe Railroad, while providing him with unparalleled opportunities and a wide audience, also ties his imagery to the burgeoning tourism industry and its commercial interests. This relationship has led to discussions about the commodification of Native American culture, where sacred ceremonies, traditional crafts, and even individuals themselves became part of the spectacle marketed to tourists. Moon's photographs, used in advertisements and souvenirs, were undeniably part of this process.

It is important to view Moon's work within its historical context. The early 20th century was a period of intense federal assimilation policies aimed at eradicating Native American languages, religions, and social structures. In this climate, artists like Moon, whatever their motivations or the critiques of their methods, also created a visual archive that, in many instances, preserved aspects of cultures under duress. His interactions with figures like the Apache leaders Magnus, Geronimo (though Geronimo died in 1909, Moon may have photographed him or other prominent Apache leaders like Alche-say, also known as Alchesay or Alchiseh), provided invaluable portraits of individuals who played significant roles in their people's history.

Later Years, Legacy, and Collections

Around 1914, Carl and Grace Moon moved from the Grand Canyon, where he had been based for some of his Fred Harvey work, to Pasadena, California. He continued to work as a painter and illustrator, and the couple pursued their collaborative book projects. His focus may have shifted somewhat from intensive field photography, but his artistic engagement with Native American themes endured.

Carl Moon passed away on June 24, 1948, in Pasadena, California, at the age of 69. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be studied and appreciated. His photographs and paintings are held in numerous prestigious collections, including the Huntington Library in San Marino, California (which holds a significant archive of his work), the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., and the Library of Congress. These collections underscore the historical and artistic importance of his contributions.

The legacy of Carl Moon is multifaceted. He was a skilled photographer who created images of striking beauty and emotional depth. His work provides a valuable, if sometimes romanticized, window into Native American life in the Southwest during a critical period of transition. He contributed significantly to the visual iconography of the American West and helped shape popular understanding (and misunderstanding) of its indigenous inhabitants.

His photographs, like those of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer from earlier generations who painted Native Americans, serve as historical documents, artistic statements, and cultural artifacts. They invite contemplation not only about the subjects depicted but also about the photographer's perspective, the cultural climate of the time, and the complex ethics of cross-cultural representation.

Enduring Significance

Carl Moon's artistic achievements and his dedication to documenting Native American cultures secure his place as an important figure in the history of American photography and Western art. His images continue to resonate, prompting reflection on the past and the enduring presence of Native American peoples. While contemporary viewers may approach his work with a more critical eye regarding issues of representation and romanticism, the power and artistry of many of his photographs remain undeniable.

His collaboration with Grace Purdie Moon on children's books also represents a significant, though perhaps less critically examined, aspect of his career, demonstrating a commitment to sharing Native American stories with a broader, younger audience. In the ongoing effort to understand the complex history of the American West and the interactions between Euro-American and Indigenous cultures, Carl Moon's lens offers a rich, though not uncomplicated, perspective. His work stands alongside that of other pioneering photographers of the West, such as Timothy H. O'Sullivan and William Henry Jackson, who, though often focused more on landscape and survey, also contributed to the visual construction of the region. Moon's specific focus on the human element within that landscape provides a unique and lasting contribution.