José Clemente Orozco stands as one of the towering figures of 20th-century art, a master muralist whose work burned with the intensity of human struggle, social upheaval, and profound philosophical questioning. Alongside Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, he formed the triumvirate known as "Los Tres Grandes" (The Three Greats), who spearheaded the Mexican Mural Renaissance, a movement that redefined public art and placed Mexico at the forefront of cultural innovation in the post-revolutionary era. Orozco's vision, however, was distinctly his own: darker, more complex, and often more tragically universal than that of his contemporaries, focusing relentlessly on the complexities of the human condition amidst the tumultuous tides of history.

His art serves as a powerful chronicle, not just of Mexico's turbulent journey through revolution and modernization, but of humanity's enduring conflicts – the clash between creation and destruction, spirit and machine, freedom and oppression. Through monumental frescoes that blaze across walls in Mexico and the United States, Orozco crafted a visual language steeped in expressionistic force and symbolic depth, leaving behind a legacy that continues to challenge and resonate with viewers today.

Formative Years and Early Sparks

José Clemente Orozco was born on November 23, 1883, in Zapotlán el Grande (now Ciudad Guzmán), Jalisco, Mexico. His family, though middle-class, faced economic instability, prompting moves that eventually brought them to Mexico City. This relocation proved pivotal. As a young boy walking to school, Orozco frequently passed the print shop of José Guadalupe Posada, whose satirical and often macabre engravings depicting calaveras (skeletons) and scenes of daily life and political commentary left an indelible mark on the budding artist. Posada's direct, popular style and sharp social critique resonated deeply, planting the seeds for Orozco's own future engagement with public themes.

Despite his family's initial hopes for him to pursue a career in architecture or agriculture, Orozco's artistic inclinations persisted. He took night classes at the prestigious Academy of San Carlos, the leading art institution in Mexico. There, he encountered instructors like Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), a key figure in promoting Mexican artistic identity and later a supporter of the mural movement. Orozco's formal training provided him with technical foundations, but his path was dramatically altered by a tragic accident in his youth. While experimenting with chemicals to make fireworks, an explosion severely damaged his left hand, leading to its eventual amputation at the wrist. This profound physical challenge, rather than deterring him, seemed to forge an even stronger resolve, channeling his energies intensely into his art.

The Crucible of Revolution

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 irrevocably shaped Orozco's worldview and artistic direction. Unlike some artists who experienced the conflict from afar or through ideological filters, Orozco was a direct witness to its chaos, violence, and human cost. He worked as a caricaturist for pro-revolution newspapers like El Ahuizote and La Vanguardia, honing his skills in sharp visual commentary. However, his experiences went beyond political cartoons; he saw firsthand the suffering, the betrayals, and the brutal realities faced by ordinary people caught in the crossfire.

This period profoundly disillusioned Orozco with simplistic revolutionary narratives. While he sympathized with the struggle against oppression, he was acutely aware of the inherent tragedy and moral ambiguities of the conflict. This perspective found early expression in a series of watercolors and drawings known as "Mexico in Revolution" and the controversial Casa de Lágrimas (House of Tears) series, which depicted the lives of prostitutes with raw empathy, challenging societal norms and causing considerable scandal. These early works already showcased his inclination towards expressionistic intensity and his focus on the darker aspects of human experience, setting him apart from more celebratory depictions of the revolutionary cause.

The Dawn of Mexican Muralism

The end of the major armed conflict of the Revolution ushered in a period of cultural reconstruction. Under the visionary leadership of José Vasconcelos, the Minister of Public Education, the government launched an ambitious program to commission large-scale murals in public buildings. The goal was twofold: to educate a largely illiterate populace about Mexican history and identity, and to foster a new national art form accessible to all. This initiative provided the fertile ground for the Mexican Mural Renaissance.

In the early 1920s, Orozco, along with Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and other artists like Jean Charlot, Fermín Revueltas, and Ramón Alva de la Canal, received commissions to paint murals at the National Preparatory School (Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso) in Mexico City. This historic building became the crucible where the movement took shape. Orozco's initial panels, such as The Elements and Man in Battle Against Nature, show him experimenting with style, moving from more classical influences towards the bolder, more dynamic forms that would characterize his mature work. Even in these early stages, his themes of struggle and his somber palette distinguished his contributions from the more decorative or overtly political works of some of his peers working alongside him.

A Triumvirate: Unity and Divergence

Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros quickly emerged as the dominant figures of the mural movement, forever linked as "Los Tres Grandes." They shared a common belief in the social function of art and the power of murals to communicate directly with the public, bypassing the exclusivity of galleries and museums. They were founding members of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, which aimed to protect artists' rights and promote a collective vision for Mexican art. Their collective impact was immense, establishing muralism as a vital force in modern art history.

Despite these shared goals, their individual artistic temperaments and political ideologies diverged significantly, leading to a dynamic interplay of collaboration and competition. Diego Rivera, perhaps the most internationally famous, embraced a more narrative and didactic style, often celebrating Mexico's indigenous heritage and the ideals of the Revolution with vibrant color and intricate detail. A committed member of the Communist Party for much of his career, his work often carried explicit political messages.

David Alfaro Siqueiros was the most politically radical and technically experimental of the three. A lifelong activist and Stalinist, his murals are characterized by dramatic, cinematic compositions, dynamic perspectives, and the innovative use of industrial materials like pyroxylin paints. His work often focused on the struggles of the proletariat and the fight against fascism.

Orozco stood apart. While deeply concerned with social justice, he remained skeptical of all political dogmas, including communism (he was sometimes labeled a "Bolshevik skeptic") and the often-sanitized official narrative of the Revolution. His art delved into the universal human condition, exploring themes of suffering, sacrifice, betrayal, and the corrupting influence of power, regardless of its ideological banner. His expressionistic style, marked by distorted figures, slashing brushwork, and a profound sense of tragedy, offered a more critical and complex perspective than either Rivera or Siqueiros. This independence often put him at odds with prevailing political currents but cemented his unique artistic voice.

The Orozco Style: Expressionism and Social Conscience

Orozco's mature artistic style is a powerful fusion of European Expressionism, particularly influences from artists like El Greco and Goya known for their dramatic intensity and emotional depth, with elements drawn from Mexican traditions, including the monumental forms of pre-Columbian sculpture and the directness of popular graphic art like Posada's. He mastered the difficult technique of true fresco painting, applying pigments to wet plaster, which demanded speed, confidence, and a clear vision.

His compositions are often characterized by dynamic, clashing diagonals, creating a sense of unease and conflict. Figures are frequently distorted, elongated, or rendered with raw, almost brutal energy to convey intense emotion. He was a master of chiaroscuro, using dramatic contrasts of light and shadow to heighten the emotional impact and sculpt forms on the wall. While capable of using vibrant color, his palette often leaned towards somber earth tones, fiery reds, oranges, and stark blacks and whites, reflecting the gravity of his themes.

Central to Orozco's work is a profound and unflinching social conscience. He relentlessly critiqued oppression, hypocrisy, and the dehumanizing effects of war, industrialization, and blind faith – whether religious or political. His murals are populated with suffering peasants, struggling workers, fallen leaders, and allegorical figures representing vast historical and philosophical forces. Unlike Rivera's often optimistic portrayal of progress, Orozco frequently depicted humanity caught in cycles of violence and self-destruction, yet always imbued with a tragic dignity and the potential for spiritual transcendence.

Masterworks in Mexico

After his initial work at the National Preparatory School, Orozco created some of his most powerful and defining murals in Mexico. One notable example is Katharsis (Catharsis), completed in 1934 for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. This tumultuous and violent fresco depicts a chaotic clash between humanity and the machine, a swirling vortex of fire, destruction, and fragmented bodies. It serves as a searing critique of modern warfare and societal decay, a vision of apocalypse born from the technological advancements of the 20th century.

However, Orozco's crowning achievement in Mexico is widely considered to be the cycle of frescoes he painted in Guadalajara between 1936 and 1939. He adorned three major public buildings: the Government Palace, the University of Guadalajara (Paraninfo), and, most significantly, the Hospicio Cabañas, a former orphanage and hospital complex (now a UNESCO World Heritage site).

In the Government Palace, his monumental depiction of the independence hero Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla wielding a fiery torch dominates the main staircase, symbolizing liberation and social justice. At the University, the dome features allegorical figures representing knowledge, creativity, and the struggles against ignorance. But it is within the Hospicio Cabañas that Orozco reached the zenith of his artistic power. Covering the walls and ceilings of the main chapel, he created a complex narrative exploring Mexico's history, from its pre-Columbian roots and the trauma of the Spanish Conquest to critiques of modern ideologies. The undisputed focal point is the staggering Hombre de Fuego (Man of Fire) in the central dome – a figure engulfed in flames, ascending towards the heavens, symbolizing both the creative and destructive potential of the human spirit. This cycle is a masterpiece of mural painting, showcasing Orozco's compositional genius, emotional depth, and philosophical complexity.

An American Sojourn

Seeking new opportunities and perhaps a respite from the political complexities of the Mexican art scene, Orozco spent a significant period, from 1927 to 1934, living and working in the United States. This period proved crucial for both his own development and his international reputation, and it left a lasting impact on American art. He initially faced challenges but gradually gained recognition, securing major commissions that allowed him to create some of his most influential works outside of Mexico. His presence, along with that of Rivera, significantly raised the profile of muralism in the US, inspiring American artists and contributing to the federal art projects of the New Deal era.

During his time in the US, Orozco engaged with the American cultural landscape, observing its dynamism, its contradictions, and its own forms of social struggle during the Great Depression. His American murals reflect these observations, tackling themes relevant to his new environment while retaining his characteristic critical edge and focus on universal human concerns. He corresponded with fellow artists like the French-born Jean Charlot, discussing art and life, further connecting the Mexican movement with broader international currents.

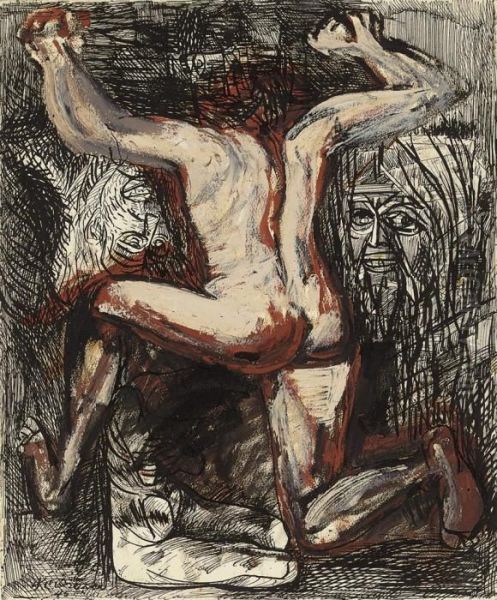

Prometheus Unbound: Pomona College

Orozco's first major commission in the United States came in 1930 at Pomona College in Claremont, California. He was invited to paint a fresco in the Frary Hall dining room. The resulting work, Prometheus, is considered the first modern fresco painted in the US by a Mexican muralist and remains a landmark of 20th-century art. Depicting the Titan from Greek mythology who stole fire from the gods to give to humanity, Orozco created a towering, tormented central figure reaching upwards, flanked by masses of humanity reacting with awe, fear, and confusion to the gift of knowledge and its inherent burdens.

The mural's raw power, dramatic composition, and profound theme exploring the double-edged nature of enlightenment and progress made a significant impact. It challenged the more decorative or academic styles prevalent at the time and introduced a new level of emotional intensity and intellectual depth to American mural painting. The work influenced numerous artists, including the California-based painter Rico Lebrun. Prometheus established Orozco's reputation in the US as a formidable artistic force.

A New World Epic: The New School

Following the success at Pomona, Orozco received a commission in 1931 to paint a mural cycle at The New School for Social Research in New York City, a center of progressive thought. Working in true fresco in a basement dining room, Orozco created a cycle titled A Call for Revolution and Universal Brotherhood. The panels depict themes of struggle, slavery, labor, and the quest for liberation across different societies and political systems.

He included panels representing the struggles in colonized nations like India and the revolutionary movements in Russia, alongside depictions of the working class and a vision of unified humanity led by figures representing diverse races. While intended to promote ideals of social justice and international solidarity, the murals were not without controversy, reflecting Orozco's typically complex and sometimes critical view of revolutionary movements themselves. This cycle further cemented his presence in the vibrant intellectual and artistic milieu of New York during the Depression era.

Dartmouth's Monumental Cycle: The Epic of American Civilization

Perhaps Orozco's most ambitious and intellectually complex work in the United States is The Epic of American Civilization, painted between 1932 and 1934 in the reserve reading room of Baker Memorial Library at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. This vast cycle, covering some 3,200 square feet, presents a panoramic and often deeply critical view of the history of the Americas, from ancient indigenous myths to the complexities and failures of modern society.

The cycle is divided into two main sections: the pre-Columbian world, focusing on the myth of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god, depicting his arrival, teachings, departure, and the prophecy of his return; and the post-Conquest world, beginning with the arrival of Hernán Cortés and the brutal realities of colonization. Orozco does not shy away from depicting the violence and destruction wrought by the Spanish, but he also critiques the perceived stagnation and sacrificial practices of the later Aztec empire.

The most controversial and powerful panels are those critiquing modern American life. Gods of the Modern World depicts skeletal academics in caps and gowns presiding over the stillbirth of knowledge from a skeleton mother on an altar of books – a scathing indictment of sterile, detached education. Other panels critique nationalism, militarism, and the dehumanizing aspects of industrial society. The cycle concludes not with a triumphant vision, but with a complex image of Modern Migration of the Spirit, suggesting a potential for redemption through Christ-like sacrifice, yet remaining ambiguous. The entire epic showcases Orozco's mastery of large-scale composition, his symbolic richness, and his unflinching willingness to confront uncomfortable truths. It provoked considerable debate upon its completion but is now recognized as a masterpiece. Notably, the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock declared it the greatest work of contemporary painting in North America. Its influence extended to American artists grappling with social themes and mural painting, such as Ben Shahn and potentially Philip Guston.

Return and Later Years

Orozco returned to Mexico in 1934, his reputation enhanced by his American successes. He embarked on the great Guadalajara commissions almost immediately, channeling his energies into the Hospicio Cabañas, Government Palace, and University murals, which represent the culmination of his artistic development. He continued to work prolifically throughout the 1940s, undertaking further mural projects, including notable works at the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation in Mexico City and the Escuela Nacional de Maestros (National Teachers College).

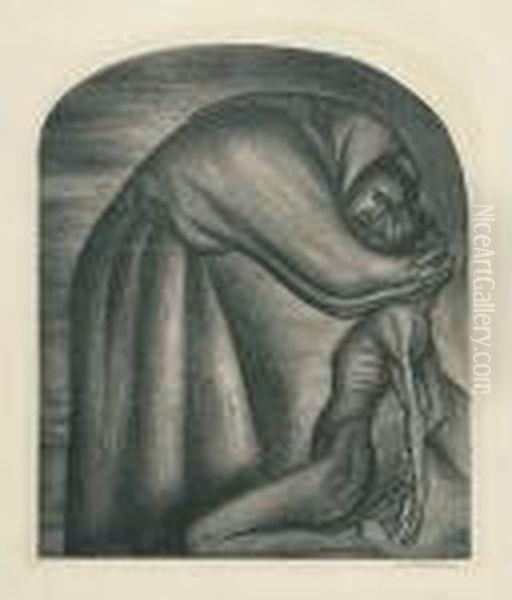

Alongside his monumental frescoes, Orozco never ceased producing easel paintings, drawings, and prints, often exploring similar themes of human struggle, social critique, and metaphysical angst on a more intimate scale. He remained a revered, if sometimes controversial, figure in Mexican cultural life. In 1947, recognizing the enduring importance of muralism, he joined Rivera and Siqueiros on a government commission to oversee future mural projects, despite their past and ongoing ideological differences. He remained artistically active until the end of his life.

Echoes Across Borders: Influence and Legacy

José Clemente Orozco's influence extends far beyond the borders of Mexico. His work provided a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing European modernism of the early 20th century, demonstrating that monumental, socially engaged art could be profoundly innovative and relevant. In the United States, his murals, particularly Prometheus and The Epic of American Civilization, directly impacted a generation of artists. Jackson Pollock's admiration is well-documented, and the raw energy and expressive force of Orozco's work can be seen as a precursor to Abstract Expressionism's emotional intensity, even if the styles differ radically.

Artists involved in the WPA Federal Art Project and other mural initiatives, like Thomas Hart Benton (though stylistically different), Philip Guston, and Ben Shahn, were certainly aware of Orozco's achievements and his powerful integration of social commentary with artistic form. His work demonstrated that muralism could be more than decorative or purely propagandistic; it could be a vehicle for profound philosophical and existential exploration. His influence can also be traced in the work of other Latin American artists engaged with social themes, such as Candido Portinari of Brazil.

Compared to his fellow "Tres Grandes," Orozco's legacy is perhaps less tied to specific political movements (unlike Siqueiros) or nationalistic narratives (unlike Rivera). His enduring power lies in his universal themes, his unflinching portrayal of the human condition – its capacity for both great cruelty and profound resilience – and the sheer expressive force of his art. He stands alongside figures like Goya as a master chronicler of the dark and dramatic aspects of human history and the individual spirit's struggle within it. Other major Mexican artists like Rufino Tamayo and Frida Kahlo, while pursuing distinct paths – Tamayo towards a more lyrical abstraction, Kahlo towards intensely personal surrealism – developed their unique voices within the vibrant artistic environment shaped by the muralists.

Navigating Controversy

Throughout his career, Orozco's work and his independent stance generated controversy. His early depictions of prostitutes in the House of Tears series shocked polite society. His critical perspective on the Mexican Revolution, refusing to romanticize its violence or outcomes, sometimes put him at odds with official narratives and more dogmatically revolutionary artists. His murals often contained anti-clerical themes, criticizing the historical role and perceived hypocrisy of the Church, which drew condemnation from conservative sectors.

His refusal to strictly align with the Communist Party, unlike Rivera and Siqueiros, made his political position complex and sometimes suspect during a highly polarized era. Furthermore, the sheer intensity, darkness, and perceived pessimism of his work were sometimes criticized, especially when contrasted with Rivera's more accessible and often optimistic style. Some found his expressionistic distortions jarring or his symbolism obscure. Yet, it is precisely this complexity, this refusal of easy answers, and this unflinching honesty that contribute to the enduring power and relevance of his art. He challenged viewers, patrons, and critics alike to confront uncomfortable truths about society and human nature.

Conclusion: The Enduring Flame

José Clemente Orozco died of heart failure in Mexico City on September 7, 1949, at the age of 65. He was buried with national honors in the Rotunda of Illustrious Persons, a testament to his immense contribution to Mexican culture. His life spanned a period of profound transformation for Mexico and the world, and his art serves as a visceral, enduring record of that turbulent era.

As one of "Los Tres Grandes," he was instrumental in forging a powerful, socially conscious public art movement that resonated globally. Yet, his unique voice – marked by its tragic grandeur, its expressionistic intensity, and its profound humanism – sets him apart. Orozco was not merely an illustrator of history or ideology; he was a philosopher in paint, grappling with the eternal questions of human existence, freedom, suffering, and transcendence. His murals, burning with a fierce, critical flame, continue to illuminate the complexities of the human spirit and challenge us to confront the dramas of our own time. His legacy is not one of simple messages, but of powerful, enduring questions etched in plaster and pigment.