Eyre Crowe (1824-1910) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. A painter of meticulous detail and keen observation, Crowe navigated the worlds of historical genre painting and burgeoning social realism, leaving behind a body of work that offers invaluable insights into the Victorian era's preoccupations, its social fabric, and its engagement with the wider world. His career, spanning from the early Victorian period to the Edwardian, witnessed profound shifts in artistic styles and societal concerns, and Crowe’s art often served as a mirror to these changes.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Transnational Context

Eyre Crowe was born in London on October 3, 1824. His upbringing was far from conventional for an English artist of his time. His father, Eyre Evans Crowe, was a respected journalist, historian, and foreign correspondent, notably for the Morning Chronicle. This profession led the family to relocate to Paris, where young Eyre spent a significant portion of his childhood and adolescence. This immersion in French culture and language from an early age would prove formative. His mother, Margaret Archer, was of German descent, further contributing to a cosmopolitan family environment.

The artistic calling came early. Following the death of his father (or a period of significant paternal absence due to work, sources vary on the exact timing relative to his studies), around 1839, Eyre Crowe enrolled in the prestigious Parisian atelier of Paul Delaroche. Delaroche was a towering figure in French academic art, renowned for his historically accurate and dramatically charged depictions of historical events, often with a focus on English history (e.g., "The Execution of Lady Jane Grey"). Delaroche's meticulous approach to research, his emphasis on precise draughtsmanship, and his ability to stage compelling narrative scenes deeply influenced Crowe. In Delaroche's studio, Crowe would have been among other aspiring artists, some of whom, like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-François Millet (though Millet's path diverged significantly), would also achieve great fame.

When Delaroche closed his Paris studio in 1843, a testament to his master's esteem, Crowe was one of the select pupils invited to accompany him to Rome. This period in Italy, though brief, exposed Crowe to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and classical antiquity, further enriching his artistic education. However, by 1844, Crowe had returned to London, ready to embark on his professional career, bringing with him a continental training that set him apart from many of his British contemporaries primarily trained within the Royal Academy Schools.

Debut at the Royal Academy and Early Career

Crowe made his debut at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1846. His first exhibited painting was "Master Prynne searching the Pockets of Archbishop Laud in the Tower." This choice of subject—a specific, somewhat recondite moment from 17th-century English history—was characteristic of the historical genre popularised by artists like Delaroche and, in Britain, figures such as Daniel Maclise and Charles West Cope. Such works appealed to a Victorian audience fascinated by historical narratives, particularly those imbued with moral or political undertones.

Throughout the late 1840s and early 1850s, Crowe continued to exhibit historical and literary subjects. His training under Delaroche was evident in the careful composition, attention to historical costume and setting, and the clear narrative thrust of these early pieces. He was building a reputation as a competent and diligent painter, though not yet one who courted major headlines or controversy. His style was precise, almost photographic in its detail, a quality that would remain a hallmark of his work.

The American Sojourn: A Turning Point

A pivotal experience in Eyre Crowe’s life and artistic development occurred between 1852 and 1853. He was invited to accompany the celebrated novelist William Makepeace Thackeray on his lecture tour of the United States. Thackeray, a family friend (his father, Eyre Evans Crowe, had known Thackeray), required a secretary and companion, and the young artist eagerly accepted the role. This journey provided Crowe with an unparalleled opportunity to observe American society firsthand, particularly in the Southern states, during a period of intense national debate over slavery.

Crowe was not merely a passive observer. Armed with his sketchbook, he meticulously documented what he saw. His diaries and drawings from this period reveal a profound engagement with the realities of American life, most notably the institution of slavery. In Richmond, Virginia, in March 1853, he witnessed a slave auction. Deeply affected, he made sketches that would later form the basis for some of his most powerful and socially conscious paintings. One anecdote recounts how, while sketching at a slave market, he drew the ire of onlookers who suspected him of being an abolitionist agitator, forcing a hasty retreat. This direct confrontation with the human cost of slavery left an indelible mark.

The American tour resulted in several significant works. "Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia" (sketched 1853, oil exhibited 1861) is perhaps the most famous. It depicts a group of enslaved men, women, and children in a stark room, their expressions a mixture of resignation, anxiety, and sorrow. The painting is notable for its unsentimental, almost documentary approach, a stark contrast to the often-romanticized or caricatured depictions of African Americans prevalent at the time. Another work, "After the Sale: Slaves Going South from Richmond" (1853/54), continued this theme, showing the forced separation of families. These paintings, exhibited in London, brought the grim realities of American slavery to a British audience, contributing to the ongoing abolitionist discourse. His experiences were also chronicled in his book, "With Thackeray in America" (1893), published much later.

The American works demonstrated a shift in Crowe’s focus. While still employing his characteristic detailed realism, the subject matter was now charged with contemporary social and moral urgency. This experience likely sowed the seeds for his later engagement with social realist themes in Britain. His depiction of American life can be seen in the context of other artists like the American Eastman Johnson, who also painted genre scenes including African American subjects, though often with a different sensibility.

A Shift Towards Social Realism in Britain

Upon his return to England, Crowe continued to paint historical and literary subjects, but the impact of his American experiences gradually began to manifest in his choice of British themes. By the mid-1860s and into the 1870s, Crowe increasingly turned his attention to contemporary British life, particularly scenes depicting the working classes and the social changes wrought by industrialization. This aligned him with the broader movement of social realism in Victorian art, championed by artists such as Ford Madox Brown ("Work"), Hubert von Herkomer ("Hard Times," "On Strike"), Luke Fildes ("Applicants to a Casual Ward"), and Frank Holl ("Newgate: Committed for Trial").

One of his most celebrated works in this vein is "The Dinner Hour, Wigan" (1874). This painting depicts female factory workers taking their midday break in the grimy industrial landscape of a Lancashire mill town. Crowe captures the scene with an ethnographic eye for detail: the women’s attire, their postures, the red-brick factories, and the smoky atmosphere. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have sentimentalized or overly dramatized such a scene, Crowe presents it with a degree of objective observation, allowing the social commentary to emerge from the faithful depiction of reality. The painting was noted for its truthfulness and its focus on the dignity of labor, even in harsh conditions.

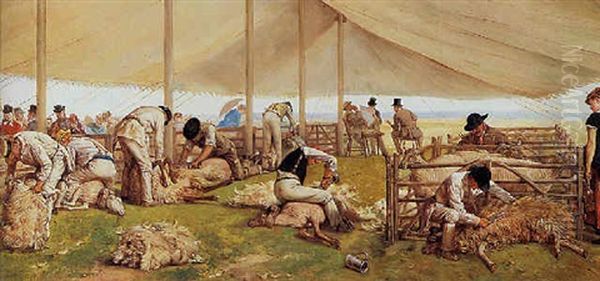

Another significant work, "A Sheep Shearing Match" (1875), set in the pastoral landscape of Llangollen, Wales, also contains subtle social commentary. While ostensibly a depiction of a rural tradition, the painting explores themes of community, skill, and perhaps the changing nature of agricultural labor. The meticulous rendering of the sheep, the shearers, and the onlookers is typical of Crowe’s style.

His painting "The Rehearsal" (1876) depicted a scene from the theatre, showcasing his versatility in capturing different aspects of contemporary life. "Sanctuary" (1877), showing a fugitive seeking refuge in a church, while historical in setting, carried strong emotional and dramatic weight, and was considered by some critics to be a high point in his career for its technical skill and narrative power.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Eyre Crowe’s artistic style was characterized by several key features:

Meticulous Realism: Influenced by Delaroche and the academic tradition, Crowe was a master of detail. His paintings often have a photographic clarity, with every element rendered with precision. This was sometimes described as being "almost like a miniature" in its fineness.

Strong Draughtsmanship: Underlying his detailed surfaces was a solid foundation in drawing. His figures are well-constructed, and his compositions carefully planned.

Narrative Clarity: Whether depicting a historical event, a literary scene, or a contemporary social tableau, Crowe ensured that the story was legible. He used gesture, expression, and the arrangement of figures and objects to convey meaning effectively.

Observational Acuity: Crowe possessed a keen eye for the nuances of human behavior and social environments. This is evident in his American slavery paintings and his British industrial scenes, where he captured telling details that lend authenticity to his depictions.

Emotional Restraint: Compared to some of his more overtly sentimental Victorian contemporaries, Crowe’s work often exhibits a degree of emotional reserve. He preferred to let the facts of the scene speak for themselves, rather than overtly manipulating the viewer’s emotions. This was particularly true of his social realist works.

Use of Light and Colour: While not an impressionist, Crowe was adept at using light to model form and create atmosphere. His palette was generally naturalistic, suited to his realist approach.

His dedication to accuracy sometimes led to criticism that his work could be somewhat dry or lacking in painterly bravura, especially as newer, looser styles like Impressionism began to gain traction. However, for audiences who valued truthfulness and detailed rendering, Crowe's work held considerable appeal. He was less concerned with the "art for art's sake" ethos that was beginning to emerge with artists like James McNeill Whistler, and more aligned with a tradition that saw art as having a narrative, moral, or social purpose.

The Royal Academy, Critical Reception, and Later Career

Eyre Crowe was a consistent exhibitor at the Royal Academy for over half a century, from 1846 until 1908. His dedication and skill were recognized in 1876 when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (A.R.A.). This was a significant honor, though he never ascended to the rank of full Royal Academician (R.A.). He also served the Academy in other capacities, including as an examiner and inspector for the Royal Academy Schools, roles that underscored his commitment to academic principles.

His critical reception was often mixed, reflecting the changing tastes of the Victorian and Edwardian art world. While his technical skill was generally acknowledged, some critics found his historical paintings old-fashioned or his social subjects too mundane. For instance, "Competitive Examination" (1862), depicting young men undergoing a civil service exam, was praised by some for its characterization but dismissed by others as a "low" or uninspiring subject.

Despite these occasional criticisms, Crowe maintained a steady career. He continued to produce works on a variety of subjects, including scenes from the lives of famous historical figures like Defoe, Swift, and Goldsmith. For example, "Dean Swift at St. James's Coffee House" (1863) and "Goldsmith's Mourners" (1863) show his continued interest in literary and historical anecdotes. He also painted scenes inspired by his travels, not just in America but also on the continent.

In his later years, Crowe’s output naturally lessened. He officially retired from the Royal Academy in 1904, receiving a pension. He remained in London, a respected, if not a leading, figure in the art establishment. His contemporary, William Powell Frith, achieved enormous popular success with panoramic scenes of modern life like "Derby Day" and "The Railway Station," which, while also detailed, often had a more bustling, anecdotal quality than Crowe's more focused social commentaries. The Pre-Raphaelites, such as John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had also carved out a distinct and influential path with their own brand of detailed realism, often infused with symbolism and medievalism, offering a different aesthetic to Crowe's more straightforward approach.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Beyond his art, a few anecdotes offer glimpses into Crowe's personality and life. The incident at the Richmond slave auction is perhaps the most telling of his character and his engagement with social issues.

There is a curious, though perhaps apocryphal or exaggerated, story involving Charles Dickens. Dickens reportedly wrote of Crowe experiencing some form of mental distress, describing an incident where Crowe was found wandering the streets in a state of undress, seemingly disoriented. The veracity and context of this account are difficult to ascertain fully, but it hints at potential personal struggles not otherwise widely documented.

His half-German heritage, through his mother, sometimes manifested in his speech, with reports of him occasionally speaking English with a slight German accent. This, combined with his French upbringing, underscored his cosmopolitan background. It's important to distinguish Eyre Crowe the artist from his namesake, Sir Eyre Crowe, a prominent British diplomat who was indeed deeply involved in Anglo-German relations in the early 20th century; the two were not directly related, though the shared name sometimes causes confusion. The artist's father, Eyre Evans Crowe, the journalist and historian, provided the intellectual and international milieu for the artist's early life.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Eyre Crowe passed away in London on December 12, 1910, at the age of 86. He left behind a substantial oeuvre that documents both historical imagination and contemporary reality through the lens of Victorian realism.

In art history, Eyre Crowe is positioned as a key practitioner of historical genre painting who successfully transitioned to social realism. His American works, particularly those dealing with slavery, are considered important documents of their time, offering a British perspective on a critical American issue. Artists like Winslow Homer would later document the Civil War and its aftermath with a different, though equally powerful, American voice.

His British social realist paintings, such as "The Dinner Hour, Wigan," contribute significantly to our understanding of Victorian working-class life and the impact of industrialization. While perhaps not as radical as the French Realism of Gustave Courbet, Crowe’s work shares a commitment to depicting the unvarnished truth of ordinary lives.

Though his fame may have been eclipsed by some of his more flamboyant or revolutionary contemporaries, Eyre Crowe's meticulous craftsmanship, his keen observational skills, and his willingness to engage with challenging social themes ensure his enduring importance. His paintings serve as valuable historical records and as compelling works of art that continue to resonate with their quiet power and integrity. His journey from the studios of Paris to the slave markets of Virginia and the factory towns of northern England reflects a life dedicated to observing and interpreting the human condition in its varied historical and social contexts. His work provides a vital thread in the rich tapestry of 19th-century art.