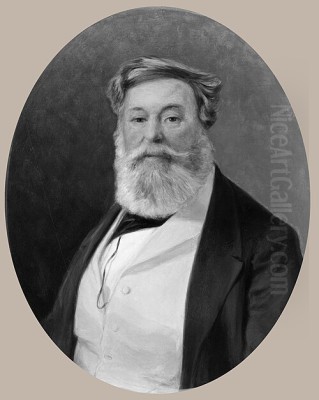

Henry Perlee Parker, an artist whose name became synonymous with vivid depictions of maritime life and the clandestine world of smugglers, carved a unique niche in 19th-century British art. His work, deeply rooted in the social and economic realities of his time, offers a compelling window into the coastal communities and working lives of Northern England, particularly around Newcastle upon Tyne.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Plymouth, Devon, on March 15, 1795, Henry Perlee Parker's early life set the stage for an artistic career that would be characterized by a keen observation of human activity, particularly in coastal settings. While details of his earliest artistic training are somewhat scarce, it is known that his family relocated, and by his early twenties, Parker was establishing himself as a professional artist.

His formative years as a painter saw him drawn to the bustling life of ports and the rugged characters who populated them. This fascination would become a recurring theme throughout his oeuvre. Parker did not emerge from the established art academies of London initially, but rather honed his skills through direct observation and practice, developing a style marked by its narrative clarity and robust realism.

Newcastle: A Canvas for a Rising Talent

The year 1815 or 1816 marked a significant turning point in Parker’s career, as he moved to Newcastle upon Tyne. This burgeoning industrial and maritime hub on the River Tyne provided him with a rich tapestry of subjects. It was here that Parker's artistic identity truly began to coalesce. He quickly became an active and prominent figure in the local art scene, which was gaining its own distinct character apart from the London-centric art world.

In Newcastle, Parker found ample inspiration in the daily lives of sailors, fishermen, miners, and, most famously, smugglers. The rugged coastline of Northumberland, with its hidden coves and fishing villages like Cullercoats, became his outdoor studio. He immersed himself in these communities, capturing their spirit with an authenticity that resonated with local audiences and beyond.

He began exhibiting his works, with records showing his participation in touring exhibitions in Newcastle as early as 1816, and later in Sheffield. His talent did not go unnoticed, and he started to build a reputation for his engaging genre scenes and character studies.

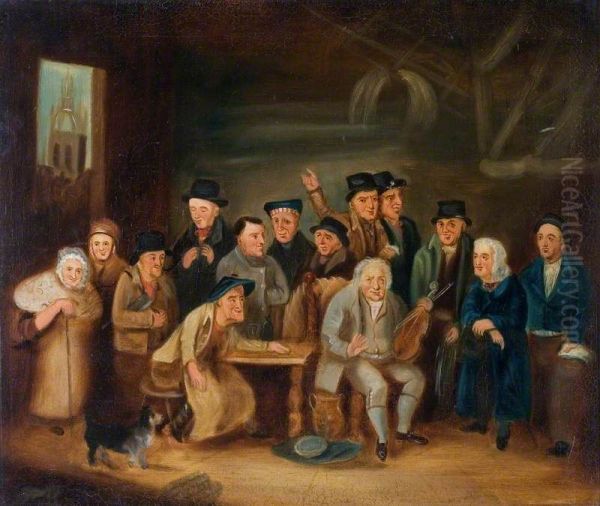

The "Smuggler Parker": A Defining Motif

Perhaps more than any other subject, Henry Perlee Parker became renowned for his depictions of smugglers. This earned him the enduring moniker "Smuggler Parker." In an era when smuggling was a widespread and often romanticized (though illegal) activity along Britain's coasts, Parker's paintings tapped into a popular fascination. His works, however, often went beyond mere romanticism, offering glimpses into the tense, secretive, and perilous lives of those involved in the illicit trade.

Paintings such as Smugglers Playing Cards (1862) exemplify this focus. In this particular piece, Parker captures a moment of uneasy leisure, the figures alert and watchful even in their recreation, hinting at the constant threat of discovery. He depicted various facets of their operations: the clandestine landings of contraband, the tense waits, the confrontations with excise men, and the camaraderie among the smugglers themselves. His ability to convey narrative and character through detailed settings and expressive figures made these works particularly compelling.

These smuggling scenes were not just dramatic inventions; they were often based on his observations and knowledge of coastal life. Parker's commitment to realism meant that the attire, equipment, and settings in his paintings were rendered with a degree of accuracy that lent them credibility. This thematic specialization distinguished him from many of his contemporaries and secured his popular appeal.

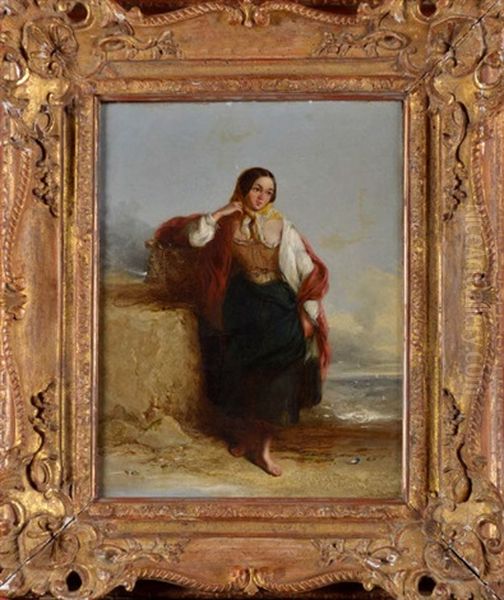

Maritime Life and Coastal Communities

Beyond the specific theme of smuggling, Parker was a dedicated chronicler of broader maritime life. The fishing communities along the Northumbrian coast, such as Cullercoats, provided him with endless subject matter. He painted fishermen mending their nets, fisherwomen selling their catch, families anxiously awaiting the return of boats, and the general hustle and bustle of harbour life.

His works often highlighted the resilience and hardiness of these coastal dwellers, whose lives were intrinsically linked to the unpredictable sea. Paintings like Waiting by the Shore or Fisherfolk on the Coast (titles of works that have appeared in auction records, reflecting common themes) would have captured these everyday scenes. He shared this interest in coastal life with other artists, such as John Wilson Carmichael (1800-1868), another prominent Newcastle-based marine painter with whom Parker was acquainted and sometimes collaborated, particularly in promoting the artistic appeal of Cullercoats.

The influence of earlier marine painters like George Morland (1763-1804), known for his rustic and coastal scenes including smuggling subjects, can be discerned in Parker’s thematic choices, though Parker developed his own distinct, often more detailed and narrative-driven style. The dramatic seascapes of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and the more tranquil marine views of Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867) formed the broader context of British marine art during Parker's active years, though Parker's focus was often more on the human element within these settings.

Social Realism and Genre Scenes

Parker's artistic interests were not confined to the coast. He also produced significant genre scenes depicting other aspects of working-class life in the North East. One of his most celebrated works in this vein is Pitmen at Play, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1836. This painting offers a lively and detailed portrayal of coal miners enjoying leisure time, possibly engaged in a game of quoits or another popular pastime. It stands as an important social document, capturing a rare glimpse into the off-duty lives of a crucial segment of the industrial workforce.

The painting Eccentric Characters of Newcastle further demonstrates his engagement with the social fabric of the city. This work, likely a series or a composite scene, would have featured the distinctive street personalities, vendors, and perhaps the urban poor, showcasing Parker's eye for character and his willingness to depict a wide spectrum of society. Such works align him with a tradition of British genre painting exemplified by artists like Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), whose scenes of everyday Scottish life were immensely popular and influential.

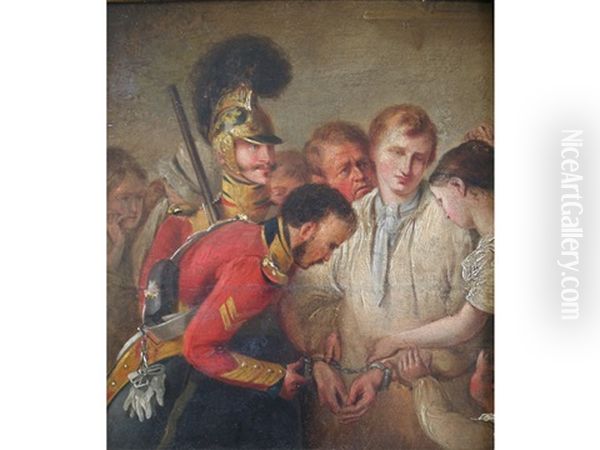

Another notable work, Securing a Deserter (1829), delves into a more dramatic social scenario, likely depicting the capture of a military or naval deserter. This painting would have combined Parker's skill in narrative composition with his interest in subjects that touched upon themes of authority, conflict, and the lives of ordinary individuals caught in challenging circumstances.

Artistic Style and Technique

Henry Perlee Parker's style was predominantly realistic, characterized by careful attention to detail, strong draftsmanship, and a clear narrative structure. He was adept at composing multi-figure scenes, imbuing his characters with individuality and conveying emotion through gesture and facial expression. His use of light and shadow was often effective in creating mood and highlighting key elements within the composition.

While he was active during a period that saw the rise of Romanticism and the pre-cursors to Victorian High Art, Parker's work remained grounded in a tradition of accessible, narrative painting. He was not an academic painter in the strictest sense, but his technical proficiency was evident. The term "strong realism" has been applied to his work, sometimes critically by those who perhaps sought more idealized or picturesque representations, particularly in his Cullercoats scenes. However, it was precisely this robustness and honesty that gave his paintings their power and appeal.

There is a mention in some analyses of his later work incorporating "Impressionist techniques with academic principles," particularly in late Victorian landscapes. Given that Parker's main exhibiting period was from the 1810s to the 1860s, and Impressionism as a defined movement emerged later, this likely refers to a broader sense of capturing atmospheric effects or a somewhat looser brushwork in his later landscapes, rather than an adoption of French Impressionist theory. His core style remained rooted in detailed observation and narrative.

Institutional Affiliations and Exhibitions

Parker was a significant figure in the development of art institutions in the North East. He was a member of the Northampton Institution for the Promotion of Art (likely a reference to the Northumberland Institution for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Newcastle, given his strong Newcastle base). Crucially, alongside Thomas Miles Richardson Sr. (1784-1848), a distinguished landscape painter, Parker co-founded the Northern Academy of Arts in Newcastle (also known as the Newcastle and Northumberland Institution for the Promotion of the Fine Arts, which later evolved). This initiative was vital for fostering local talent and providing a platform for artists in the region.

His work was not confined to local exhibitions. Parker sought recognition on a national stage, exhibiting regularly at prestigious London venues. He showed works at the Royal Academy from 1817 to 1863, a significant span that indicates a consistent level of acceptance and quality. He also exhibited at the British Institution and other London galleries. This dual presence, active both locally in Newcastle and nationally in London, highlights his ambition and the regard in which his work was held.

The Grace Darling Connection: A Humanitarian Narrative

One of the most notable episodes in Parker's career involves his connection to Grace Darling, the lighthouse keeper's daughter who, with her father, famously rescued survivors from the wreck of the SS Forfarshire in 1838. This heroic act captured the public imagination, and Parker, like many artists and writers of the time, was moved by the story.

He developed a friendship with the Darling family and painted several works related to the rescue and to Grace herself. One significant painting depicted the Interior of the Longstone Lighthouse, showing Grace and her father, William. This work was not just a portrayal of a famous event but also an intimate glimpse into the setting of the heroism. Parker's connection was personal enough that he reportedly named one of his daughters Grace Darling Parker. These paintings contributed to the burgeoning Grace Darling iconography and further cemented Parker's reputation as an artist attuned to contemporary events and human drama. The narrative power of such subjects was also explored by other Victorian painters like Edwin Landseer (1802-1873), though Landseer focused more on animals and Scottish scenes.

Collaborations and Artistic Circle

Parker was part of an active artistic community. His collaboration with John Wilson Carmichael in promoting Cullercoats as an artists' colony has already been noted. He also worked with the engraver William O. Geller (active c. 1830s-1850s) on producing prints after his paintings, such as The Covenanter. This was a common practice for popular artists, allowing their work to reach a wider audience.

The artistic environment in Newcastle during Parker's time also included figures like the renowned wood engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), whose influence on Northern art and illustration was profound, though Bewick was of an earlier generation. The dramatic and often sublime works of John Martin (1789-1854), another artist with Northumbrian roots, offered a contrasting artistic vision to Parker's more grounded realism. Parker's focus on genre and narrative found parallels in the work of many Victorian contemporaries who sought to capture the diverse facets of British life.

Later Career, Move to London, and Final Years

Around 1840-1841, after a period of significant success and activity in Newcastle and a brief stint in Sheffield (1840-41, where he taught at the Sheffield School of Design), Parker made the decision to move to London. This was a common trajectory for ambitious provincial artists seeking broader recognition and patronage in the nation's artistic capital. He continued to exhibit, including at the Royal Academy, for several more decades.

Despite his earlier successes and continued artistic output, Parker's later years were marked by financial hardship. The art market could be fickle, and tastes changed. It is a poignant fact that Henry Perlee Parker, an artist who had contributed so much to the visual record of his time and had been a leading figure in Newcastle's art scene, died in poverty in Shepherd's Bush, London, on November 11, 1873. He was reportedly destitute at the time of his death.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Despite the sad circumstances of his final years, Henry Perlee Parker's artistic contributions have endured. His paintings are valued not only for their artistic merit but also as important historical documents, offering insights into 19th-century maritime and working-class life, particularly in the North East of England.

His work is held in various public collections, including the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle and the Wellcome Collection in London. The Laing Art Gallery notably held a significant retrospective exhibition of his work in 1969-1970, which played a role in re-evaluating his contribution to British art and bringing his oeuvre to a new generation. This exhibition also brought to light records of his picture sales.

Further archival material, such as two albums held at the Yale Center for British Art, Rare Books and Manuscripts, provides valuable information. These albums document 66 paintings sold by Parker between 1822 and 1837, complete with details of the buyers, offering a fascinating glimpse into his patronage and the market for his work during his peak Newcastle period.

Parker's paintings continue to appear at auction, with works like Pitmen at Play and various smuggling and coastal scenes commanding interest from collectors. His depiction of Cullercoats also prefigures the later interest in the village by artists like the American Winslow Homer (1836-1910), who stayed there in 1881-1882, capturing its rugged beauty and the stoicism of its inhabitants, demonstrating the enduring appeal of the subjects Parker had pioneered.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Henry Perlee Parker was more than just "Smuggler Parker." He was a versatile and observant artist who captured a wide range of human experience with empathy and skill. From the dramatic tension of illicit trade to the everyday toil of fishermen and miners, and the poignant heroism of Grace Darling, his canvases tell compelling stories. His role in establishing art institutions in Newcastle and his consistent presence in national exhibitions underscore his significance.

Though his life ended in hardship, his artistic legacy provides a rich and detailed visual account of a transformative period in British history. His paintings remain a testament to the lives of ordinary people, the allure of the sea, and the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity and adventure. As an art historian, one appreciates Parker not just for individual works, but for the cohesive vision he offered of a specific time and place, rendered with a realism and narrative power that continues to engage viewers today. His contribution to the regional identity of Northumbrian art, and to the broader tapestry of British genre painting, is undeniable and worthy of continued study and appreciation.