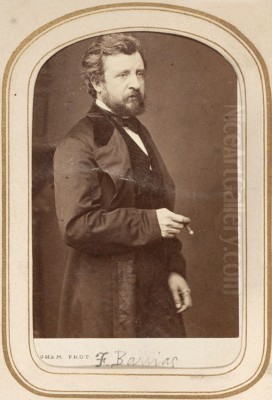

Félix-Joseph Barrias (1822–1907) was a distinguished French painter whose career spanned a significant period of artistic transformation in the 19th century. Born in Paris, a city then solidifying its status as the art capital of the world, Barrias navigated the currents of Neoclassicism and Romanticism, ultimately forging a style that synthesized elements of both. His contributions extended beyond his own canvases; he was also an influential teacher and a creator of significant public murals, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of his time. His long life allowed him to witness the decline of academic art's dominance and the rise of revolutionary movements like Impressionism, yet he remained a respected figure within the established art institutions.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Félix-Joseph Barrias was born into a family with strong artistic leanings on May 13, 1822, in Paris. His father, himself a painter specializing in ceramics, undoubtedly provided an early exposure to the world of art and craftsmanship. This familial environment fostered creativity, a trait also evident in his younger brother, Louis-Ernest Barrias (1841–1905), who would go on to become a highly acclaimed sculptor. Growing up in such a household, it is likely that young Félix-Joseph was encouraged to develop his artistic talents from an early age, surrounded by the tools and discussions of the trade. This foundation was crucial in a period where artistic training often began informally within the family or a master's studio before progressing to more formal institutions.

The Paris of Barrias's youth was a vibrant center of artistic debate and production. The legacy of Jacques-Louis David, though he had died in exile, still loomed large, and Neoclassicism remained a powerful force. Simultaneously, the passionate and dramatic expressions of Romanticism, championed by artists like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault, were capturing the imagination of a new generation. It was into this dynamic and often contentious artistic milieu that Barrias would step as he embarked on his formal training, equipped with a familial grounding in the arts.

Formal Artistic Training

To hone his burgeoning talent, Félix-Joseph Barrias sought instruction from some of the leading academic painters of his day. He became a student of Léon Cogniet (1794–1880), a prominent historical and portrait painter who had himself won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1817. Cogniet was known for his meticulous technique and his ability to capture dramatic historical scenes, qualities that would have resonated with the academic curriculum of the time. Under Cogniet's tutelage, Barrias would have received rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and composition, the foundational skills deemed essential for a successful academic painter.

Barrias furthered his education at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the leading art institution in France. Here, he also studied under Pierre-Jules Cavelier (1814–1894), a sculptor who, like Cogniet, was a product of the academic system and a Prix de Rome winner. While Cavelier was primarily a sculptor, his understanding of form, anatomy, and classical ideals would have complemented Barrias's training as a painter. The École des Beaux-Arts emphasized the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters, instilling in its students a reverence for tradition and a pursuit of idealized beauty. This environment shaped Barrias's early artistic development, grounding him firmly in the academic tradition.

The Prix de Rome and its Impact

A pivotal moment in Barrias's early career came in 1844 when he was awarded the coveted Prix de Rome for painting. This prize, established in the 17th century, was the highest honor for young artists in France, granting them a scholarship to study at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the Villa Medici. Winning the Prix de Rome was a significant achievement, signaling official recognition of an artist's talent and promising a bright future within the academic system. Barrias won the prize for his painting "Cincinnatus Receiving the Deputies of the Senate," a work that exemplified the neoclassical ideals of civic virtue, historical accuracy, and clear, balanced composition, themes highly favored by the Academy.

The years spent in Rome were transformative for many artists, and Barrias was no exception. Immersion in the art and culture of Italy provided firsthand exposure to the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. He would have studied the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, and other Italian masters, absorbing their techniques, compositions, and understanding of the human form. This direct engagement with the sources of Neoclassicism deepened his appreciation for its principles, but the rich artistic environment of Italy, with its dramatic landscapes and vibrant local color, also likely nurtured the more Romantic sensibilities that would later emerge in his work. The experience in Rome solidified his technical skills and broadened his artistic horizons, preparing him for a successful career upon his return to Paris.

Artistic Style: A Blend of Neoclassicism and Romanticism

Upon his return to Paris and throughout his career, Félix-Joseph Barrias developed an artistic style that skillfully blended the prevailing, and often competing, aesthetics of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. From Neoclassicism, he retained a commitment to clear composition, precise draughtsmanship, and often, subjects drawn from history, mythology, or classical literature. His figures were typically well-defined, and his narratives were presented with a sense of order and gravitas, echoing the ideals promoted by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a towering figure of French Neoclassicism.

However, Barrias's work was not coldly academic. He infused his paintings with a Romantic sensibility, evident in his choice of dramatic moments, his exploration of emotional states, and a richer, more evocative use of color and light than typically found in stricter Neoclassical works. This Romantic inclination allowed for greater personal expression and a focus on the subjective experience, aligning him with the spirit of artists like Delacroix, though Barrias's Romanticism was generally more restrained and tempered by his academic training. This synthesis allowed him to appeal to a broad audience and to navigate the evolving tastes of the Salon juries. His ability to balance classical structure with emotional depth became a hallmark of his mature style.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Barrias produced a significant body of work throughout his career, encompassing historical scenes, mythological subjects, religious paintings, portraits, and genre scenes. His Prix de Rome-winning "Cincinnatus Receiving the Deputies of the Senate" (1844) established his reputation as a history painter capable of handling complex compositions and noble themes. This work depicted the Roman patrician Cincinnatus being called from his plow to lead Rome as dictator, a story lauding duty and selflessness.

One of his most famous paintings is "The Death of Chopin" (La Mort de Chopin), completed in 1885. This work captures the poignant final moments of the composer Frédéric Chopin, surrounded by grieving friends and admirers. The painting is imbued with a Romantic sense of melancholy and reverence for artistic genius. The careful rendering of the figures, the dramatic lighting, and the palpable emotion of the scene showcase Barrias's ability to combine academic precision with heartfelt sentiment. The presence of figures like George Sand's son, Marcelina Czartoryska (a Polish princess and Chopin's pupil, often depicted at the piano in such scenes), and the artist Eugène Delacroix (a close friend of Chopin) would have resonated with contemporary audiences familiar with Chopin's circle.

Another notable work, often cited, is "The Nest" (Le Nid d'oiseaux). While specific details of this painting might vary in interpretation or if multiple works share this title, it generally points towards a more intimate, perhaps allegorical or genre scene, possibly reflecting themes of domesticity, nature, or innocence. Such works allowed artists to explore more personal or sentimental themes, often appealing to the burgeoning middle-class art market. His versatility also extended to large-scale decorative projects.

Mural Paintings and Public Commissions

Beyond easel painting, Félix-Joseph Barrias made significant contributions to the tradition of mural painting in France. He received several important public commissions to decorate prominent buildings, a testament to his standing within the artistic establishment. Mural painting was considered a high form of art, allowing artists to engage with large architectural spaces and to convey grand historical, allegorical, or religious narratives to a wide public.

Barrias executed murals for the Louvre Museum in Paris, one of the most prestigious cultural institutions in the world. Contributing to the decoration of the Louvre placed him in the company of France's most celebrated artists. He also created murals for other significant locations, including the Church of Saint-Eustache in Paris and the Grand Opéra de Paris (Palais Garnier), where he contributed to the elaborate decorative schemes conceived by Charles Garnier. These commissions required not only artistic skill but also the ability to work on a monumental scale and to integrate paintings harmoniously with architecture. His work in this domain, alongside contemporaries like Paul Baudry (who famously decorated the Grand Foyer of the Opéra Garnier) and Gustave Boulanger, demonstrates his mastery of large-scale composition and his role in shaping the visual culture of public spaces in 19th-century Paris.

Teaching and Influence on Other Artists

Félix-Joseph Barrias was not only a prolific painter but also a dedicated and influential teacher. He maintained a studio and taught at his own art school, guiding numerous aspiring artists. His approach to teaching likely emphasized the strong academic foundation he himself had received, focusing on rigorous drawing practice, anatomical study, and the principles of composition. However, his own blend of Neoclassicism and Romanticism suggests he may have encouraged students to find their own balance between tradition and personal expression.

Among his most notable pupils was Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who would later become a leading figure of Impressionism. Degas studied briefly with Barrias before entering the École des Beaux-Arts under Louis Lamothe, a disciple of Ingres. While Degas's mature style diverged significantly from Barrias's academicism, the early training in draughtsmanship would have provided a crucial foundation. Other students included Jean Georges Vibert (1840–1902), known for his highly detailed and often humorous genre scenes featuring cardinals, and Gustave Pinel. Jules Tavernier, who later gained fame for his depictions of Hawaiian volcanoes and Californian landscapes, also received instruction from Barrias. Through his teaching, Barrias played a role in shaping the next generation of artists, even those who would ultimately challenge the academic tradition he represented.

Collaborations and Professional Relationships

In the highly structured art world of 19th-century Paris, professional relationships and collaborations were common, particularly for large-scale decorative projects. Barrias is known to have collaborated with other artists on such commissions. For instance, his work on decorative schemes for public buildings often involved working alongside other painters and sculptors under the direction of an architect or a chief artist. His participation in projects like the decoration of the Paris Opéra, alongside artists like Paul Baudry and Gustave Boulanger, highlights this collaborative aspect of his career.

Barrias also maintained relationships with a wide range of contemporaries. He would have interacted with fellow academicians, Salon jurors, and critics. His artistic circle would have included artists whose styles varied, from staunch defenders of the academic tradition like Jean-Léon Gérôme or William-Adolphe Bouguereau, to those exploring different paths. He had contact with figures like Gustave Courbet, the standard-bearer of Realism, and Ernest Hébert, a painter whose sentimental and often melancholic style found favor with the public. These interactions, whether collaborative, competitive, or collegial, were part of the fabric of an artist's life, shaping their careers and influencing the broader artistic discourse of the period. His brother, the sculptor Louis-Ernest Barrias, would also have been a significant professional and personal connection.

The Salon and Official Recognition

Throughout his career, Félix-Joseph Barrias regularly exhibited his work at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain public recognition, attract patrons, and secure commissions. Success at the Salon could make or break an artist's career. Barrias's ability to consistently have his works accepted and often favorably reviewed indicates his skill in meeting the expectations of the Salon juries, which generally favored historical subjects, mythological scenes, and religious paintings executed with technical proficiency and adherence to academic conventions.

His contributions to French art were recognized with several prestigious honors. He was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Légion d'Honneur in 1859 (some sources state 1878, but 1859 is more commonly cited for the initial award, with later promotions), a significant mark of distinction. He was subsequently promoted to Officier (Officer) of the Légion d'Honneur in 1881, and finally to Commandeur (Commander) in 1900. These accolades, bestowed by the French government, underscored his status as a respected and accomplished artist who upheld the values of the French artistic tradition. Such recognition was crucial for an artist working within the academic system, affirming their contributions to national culture.

Later Career and Evolving Artistic Landscape

Barrias continued to paint and exhibit into his later years, witnessing profound changes in the art world. The late 19th century saw the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism, movements that challenged the very foundations of academic art. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent van Gogh were forging new visual languages that prioritized subjective perception, fleeting moments, and expressive color over traditional notions of finish, historical narrative, and idealized form.

While Barrias remained largely faithful to his academic training and his synthesis of Neoclassical and Romantic elements, the artistic environment around him was undeniably shifting. The Salon itself began to lose its monolithic authority as alternative exhibition venues, such as the Salon des Refusés and independent Impressionist exhibitions, emerged. Despite these changes, Barrias continued to be a respected figure, representing a tradition that, while no longer dominant, still held value for many. His later works likely continued to reflect his established style, perhaps with subtle adaptations or a deepening of his characteristic sentiment. He passed away in Paris on January 24, 1907, at the age of 84.

Legacy and Conclusion

Félix-Joseph Barrias occupies a significant, if sometimes overlooked, place in the history of 19th-century French art. He was a master of the academic tradition, yet his work was enlivened by a Romantic sensibility that resonated with the tastes of his time. His paintings, whether grand historical narratives, poignant scenes like "The Death of Chopin," or decorative murals, were characterized by technical skill, thoughtful composition, and an ability to convey emotion.

His legacy also lies in his role as an educator. Through his teaching, he influenced a generation of artists, including figures like Edgar Degas, who, despite taking radically different artistic paths, benefited from the foundational training he provided. Barrias's career exemplifies the life of a successful academic artist in 19th-century Paris: winning the Prix de Rome, securing public commissions, exhibiting regularly at the Salon, and receiving official honors.

While his name may not be as widely recognized today as those of the Impressionist revolutionaries or the great Romantic masters like Delacroix, Félix-Joseph Barrias was a vital contributor to the rich and complex artistic fabric of his era. He skillfully navigated the dominant artistic currents, creating a body of work that reflects both the enduring power of tradition and the evolving sentiments of a changing world. His art serves as a valuable window into the mainstream artistic production of a period that laid the groundwork for modern art, and his dedication to his craft and his students ensured his influence extended beyond his own lifetime.