Fidelia Bridges (1834–1923) stands as a unique and cherished figure in nineteenth-century American art. Renowned for her exquisitely detailed depictions of birds, flowers, and natural scenes, she carved out a successful career in an era when professional female artists were a rarity. Primarily a master of watercolor, Bridges combined the meticulous observation championed by the Pre-Raphaelite movement with a deeply personal, almost poetic sensibility. Her ability to capture the intimate beauty of the natural world, often in its most unassuming forms, resonated with the public and secured her a lasting place in art history, not only for her artistic skill but also for her pioneering spirit.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1834, Fidelia Bridges' early life was marked by hardship. The daughter of a sea captain, Henry Gardiner Bridges, and Eliza Chadwick Bridges, she experienced profound loss at a young age. Her father died in Macao, China, in 1849, and her mother passed away just months later. Orphaned as a teenager, Fidelia and her younger sister Clara were left in the care of family friends and relatives. This period of instability undoubtedly shaped her character, fostering resilience and a keen observational capacity.

The Bridges sisters eventually found a supportive environment in Brooklyn, New York, where they lived with the family of William Augustus Brown, a Quaker. Fidelia took on the role of a mother's assistant, or governess, to the Brown children. It was during this time, in the bustling artistic environment of New York, that her nascent artistic talents began to find an outlet. The city was a hub for artists, and exposure to this world, however indirect, likely fueled her ambitions.

The Guiding Hand of William Trost Richards and Pre-Raphaelitism

A pivotal moment in Bridges' artistic development came in the early 1860s when she sought formal instruction. She became a student of William Trost Richards, a prominent American painter associated with both the Hudson River School and the burgeoning American Pre-Raphaelite movement. Richards had a studio in Philadelphia and was a respected instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Under his tutelage, Bridges honed her skills in drawing and oil painting.

Richards was a fervent advocate for the principles espoused by the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded by artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. These artists, inspired by the writings of critic John Ruskin, championed "truth to nature," emphasizing meticulous detail, vibrant color, and a rejection of academic conventions. Ruskin's call to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing" became a guiding mantra. Richards instilled these ideals in Bridges, encouraging her to observe nature with scientific precision and render it with utmost fidelity.

The American Pre-Raphaelite movement, though smaller and less cohesive than its British counterpart, included artists such as Thomas Charles Farrer, John William Hill, and John Henry Hill. These artists shared a commitment to detailed naturalism, often focusing on botanical studies and intimate landscapes. Bridges' work from this period reflects this influence, showing a dedication to capturing the specific textures, forms, and colors of individual plants and flowers.

A Master of Watercolor: Capturing Nature's Intimacy

While Fidelia Bridges initially worked in oils, she soon found her true calling in watercolor. This medium, with its transparency and immediacy, proved perfectly suited to her delicate touch and her desire to capture the fleeting beauty of the natural world. Her watercolors are characterized by their refined detail, subtle gradations of color, and an almost jewel-like precision. She developed an extraordinary ability to render the intricate structures of flowers, the delicate plumage of birds, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow.

Her subjects were often drawn from the immediate surroundings of her various homes and sketching grounds, particularly in New England and later in Canaan, Connecticut, where she eventually settled. She had a particular fondness for wildflowers, ferns, grasses, and small songbirds, often depicted in their natural habitats. Works like Thrush's Nest, Milkweed, and Daisies in a Meadow exemplify her approach. These are not grand, panoramic landscapes in the tradition of Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt of the Hudson River School, but rather intimate close-ups, inviting the viewer to appreciate the beauty in small, often overlooked details.

Bridges' compositions often feature a shallow depth of field, focusing attention on the primary subject against a softly rendered background. This technique, combined with her precise brushwork, gives her paintings a sense of quiet contemplation and reverence for nature. Her ability to convey the specific character of each plant or bird, while also imbuing the scene with a gentle, lyrical quality, led critics to describe her works as "little poetic lyrics."

Commercial Success and the Chromolithographs of Louis Prang

One of the most remarkable aspects of Fidelia Bridges' career was her commercial success, particularly her long and fruitful collaboration with the renowned lithographer and publisher Louis Prang. Prang, often called the "father of the American Christmas card," was a pioneer in chromolithography, a process that allowed for the mass production of high-quality color prints. He recognized the appeal of Bridges' delicate and charming nature studies and saw their potential for a wide audience.

Beginning in the 1870s and continuing for over fifteen years, Bridges created numerous designs for Prang & Company. These were reproduced as greeting cards, calendar illustrations, and prints for albums and books. Her images of birds, flowers, and seasonal scenes became immensely popular, adorning countless Victorian homes. This collaboration provided Bridges with a steady income and a level of financial independence rarely achieved by female artists of her time. It also made her work accessible to a broad public, far beyond the traditional art market of galleries and exhibitions.

While some artists might have viewed commercial illustration as a lesser pursuit, Bridges approached it with the same dedication and artistic integrity she brought to her exhibition watercolors. Her designs for Prang maintained her characteristic attention to detail and her sensitive portrayal of nature. This work played a significant role in popularizing nature imagery in American visual culture and demonstrated that fine art and commercial art were not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The Influence of Japanese Art

During the late nineteenth century, Western art was significantly impacted by Japonisme, a fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics. Fidelia Bridges was not immune to this influence. Her brother, Henry Bridges, was a tea taster who traveled to Asia and brought back Japanese artworks, including woodblock prints. It is documented that Bridges had access to prints by masters such as Utagawa Hiroshige, particularly his kachō-ga (flower-and-bird pictures).

While Bridges' style remained rooted in Western naturalism, subtle influences from Japanese art can be discerned in some of her compositions. These might include a heightened sense of asymmetry, a focus on flattened space, or a particular elegance in the arrangement of natural elements. The Japanese emphasis on the decorative qualities of nature and the intimate portrayal of birds and flowers would have resonated with her own artistic inclinations. The way Japanese artists like Hiroshige or Katsushika Hokusai could isolate a single branch of blossoms or a bird on a reed, imbuing it with profound beauty, likely offered her a complementary perspective to her Pre-Raphaelite training.

Her visit to England in 1879-1880 would have further exposed her to Asian art collections and the ongoing dialogue about Eastern influences in Western art, a topic of interest to artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who was actively incorporating Japanese principles into his work.

A Woman in a Man's Art World: Networks and Recognition

Fidelia Bridges navigated the predominantly male art world of the nineteenth century with quiet determination and considerable success. She was one of the earliest female members of the American Watercolor Society (AWS), elected in 1873, a significant achievement that placed her among the leading watercolorists in the country. She regularly exhibited her work at the AWS annual exhibitions, as well as at the National Academy of Design in New York, the Brooklyn Art Association, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

She formed important friendships and professional associations. Her relationship with her teacher, William Trost Richards, remained a source of support throughout her career; he even painted her garden. She was also close friends with the sculptor Anne Whitney, another pioneering female artist who challenged societal expectations. Bridges, Whitney, and other women artists often formed supportive networks, sharing studios, traveling together (Bridges and Whitney reportedly visited Europe together), and encouraging each other's professional endeavors. These networks were crucial for women seeking to establish themselves in the art world.

While Bridges may not have been as overtly radical as some of her contemporaries, her consistent professionalism, the quality of her work, and her ability to sustain a long and successful career served as an important example. She demonstrated that a woman could achieve artistic excellence and financial independence through her art. Her success, alongside that of other notable American women artists of the period such as Mary Cassatt, Cecilia Beaux, and Lilly Martin Spencer (though their styles and subjects differed greatly), contributed to the gradual opening of opportunities for women in the arts. Even in sculpture, women like Harriet Hosmer and Edmonia Lewis were making significant inroads.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Fidelia Bridges' oeuvre is characterized by its consistent quality and thematic focus. Several works stand out as particularly representative of her style and preoccupations:

Thrush's Nest: This subject, which she revisited in several variations, showcases her ability to capture the intimate details of avian life. The delicate construction of the nest, the speckled eggs, and the surrounding foliage are rendered with exquisite precision. There is a sense of quiet observation, as if the viewer has stumbled upon a hidden secret of nature.

Milkweed (often titled Wildflowers or similar, depicting Asclepias syriaca): Bridges frequently painted common wildflowers, elevating them to subjects of artistic contemplation. Her depictions of milkweed, with its complex flower heads and distinctive pods, highlight her botanical accuracy and her appreciation for the beauty of often-overlooked plants.

Daisies in a Meadow: This work, and others like it, captures the simple charm of a field of wildflowers. Bridges excels at conveying the texture of the grasses and the delicate forms of the daisy petals, often including small birds or insects to animate the scene.

Study of Ferns: Ferns, with their intricate fronds and varied textures, were a favorite subject. These studies demonstrate her mastery of detail and her ability to differentiate between various species, reflecting the Victorian era's passion for botany.

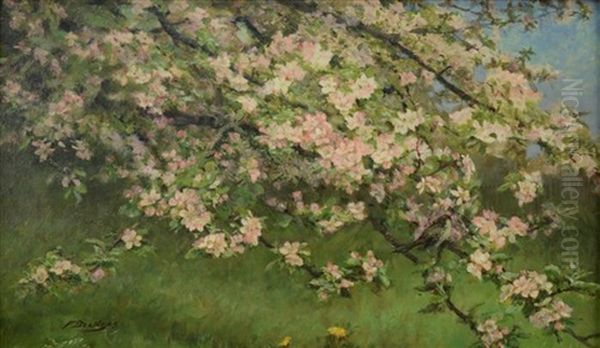

Wisteria on a Wall: This subject allowed Bridges to explore the graceful, cascading forms of flowering vines. The interplay of blossoms, leaves, and the supporting structure (often a stone wall or trellis) creates a rich tapestry of color and texture.

Titmouse and Thistle: Combining her love for birds and plants, works like this capture a fleeting moment in nature. The alert posture of the bird and the spiky form of the thistle are rendered with both accuracy and charm.

Her body of work, though focused on a relatively narrow range of subjects, reveals a profound and sustained engagement with the natural world. Each painting is a testament to her patient observation and her deep affection for her subjects.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

In the 1890s, Fidelia Bridges moved to Canaan, Connecticut, a quiet town in the Litchfield Hills. Here, she continued to paint, finding ample inspiration in the surrounding countryside. She lived a relatively secluded life, dedicated to her art and her garden. She never married, and her art remained her central focus until her death in Canaan in 1923.

Fidelia Bridges' legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, she is recognized as one of America's finest watercolorists of the nineteenth century and a key figure in the American Pre-Raphaelite movement, notable for being its most prominent female adherent. Her work demonstrates a unique fusion of scientific accuracy and poetic sensibility, capturing the delicate beauty of nature with unparalleled intimacy.

As a pioneering female artist, she achieved a level of professional success and financial independence that was rare for women of her time. Her long collaboration with Louis Prang brought her art to a wide audience, blurring the lines between fine art and popular illustration and contributing to the Victorian era's appreciation for nature imagery.

Her paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, their charm, and their heartfelt depiction of the natural world. They are held in numerous museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the National Gallery of Art. Fidelia Bridges' "little poetic lyrics" in watercolor remain a testament to her keen eye, her delicate hand, and her enduring love for the quiet corners of nature. Her contribution to American art, both as a skilled painter of nature and as a woman who forged her own path, ensures her a respected and lasting place in its history. She stands alongside artists like Martin Johnson Heade, who also specialized in detailed depictions of hummingbirds and tropical flowers, in her focused dedication to capturing the minute wonders of the natural world.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Fidelia Bridges carved a distinct niche for herself within the broader currents of nineteenth-century American art. Her unwavering focus on the intimate details of nature, rendered with Pre-Raphaelite precision and a deeply personal lyricism, set her apart. She was not a painter of grand, sublime landscapes like her Hudson River School contemporaries, nor an Impressionist capturing fleeting effects of light like Childe Hassam or Theodore Robinson would later become. Instead, she invited viewers into a miniature world of birds, nests, flowers, and ferns, revealing the profound beauty inherent in these often-overlooked subjects.

Her success as a professional artist, particularly her ability to support herself through her work and her popular illustrations for Louis Prang, was a significant achievement for a woman in her era. While artists like Winslow Homer also found success in illustration before focusing on easel painting, Bridges maintained a strong presence in both realms. Her dedication to her craft, her mastery of watercolor, and her unique artistic vision ensure that Fidelia Bridges remains a significant and beloved figure in the story of American art, a testament to the power of a delicate brush guided by a resolute spirit.