John William Inchbold (29 April 1830 – 23 January 1888) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. A painter deeply imbued with the spirit of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Inchbold dedicated his career to capturing the minute details and profound beauty of the natural world. His canvases, often characterized by their meticulous rendering and vibrant, jewel-like colours, reflect a profound engagement with nature, influenced by the aesthetic philosophies of his time and the guidance of prominent figures like John Ruskin. Though his life was marked by periods of travel, artistic struggle, and a somewhat solitary disposition, Inchbold's legacy endures through works that continue to resonate with their poetic intensity and unwavering commitment to "truth to nature."

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Leeds

John William Inchbold was born in Leeds, Yorkshire, on April 29, 1830. His father, Thomas Inchbold, was a respected figure in the local community, serving as the editor and proprietor of the Leeds Intelligencer, a prominent local newspaper. This environment, while not directly artistic, likely fostered an appreciation for observation and communication. From an early age, Inchbold displayed a clear aptitude for drawing and a keen interest in the visual arts.

His formal artistic training began with an apprenticeship in lithography at the London firm of Day & Haghe. Lithography, with its emphasis on precise drawing and tonal variation, would have provided a solid foundation for his later detailed work in oil and watercolour. Seeking to further hone his skills, he subsequently became a pupil of the watercolourist Louis Haghe, one of the principals of the firm and a respected artist in his own right. This tutelage undoubtedly refined Inchbold's handling of watercolour, a medium he would continue to use with great sensitivity throughout his career.

In 1847, at the age of seventeen, Inchbold took a significant step in his artistic development by enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the traditional training ground for aspiring artists in Britain, offering instruction in drawing from the antique and the life model, as well as lectures on perspective and anatomy. While the Academy's teachings were often rooted in classical ideals, the period was also one of artistic ferment, with new ideas beginning to challenge established conventions.

The Embrace of Pre-Raphaelitism

Inchbold's emergence as an artist coincided with the rise of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This group, along with other artists who shared their ideals, sought to revitalize British art by rejecting the perceived artificiality and academicism that had, in their view, stemmed from the influence of High Renaissance masters like Raphael. Instead, they advocated a return to the detailed observation, vibrant colour, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Early Netherlandish art. "Truth to nature" became their guiding principle, leading them to paint directly from the subject, often outdoors, with meticulous attention to every detail.

Inchbold was profoundly drawn to these ideals. Though perhaps not a formal member of the core Brotherhood, his work from the early 1850s onwards clearly aligns with Pre-Raphaelite tenets, particularly in the realm of landscape painting. He began exhibiting his works, with his first showing at the Society of British Artists in 1849, followed by his debut at the Royal Academy in 1850 or 1851. His early landscapes quickly demonstrated a commitment to rendering natural forms with an almost scientific precision, combined with a poetic sensibility.

A pivotal figure in Inchbold's career, and indeed for the entire Pre-Raphaelite movement, was the influential art critic and writer John Ruskin. Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites for their dedication to capturing the truth of the natural world, urging young artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing." Inchbold's work resonated deeply with Ruskin's philosophy. The critic became an admirer and patron, offering both encouragement and, at times, pointed advice. Ruskin's support lent considerable weight to Inchbold's burgeoning reputation and helped to solidify his position as a leading exponent of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting.

Masterworks of Meticulous Observation

Inchbold's oeuvre is distinguished by several key works that exemplify his Pre-Raphaelite approach to landscape. One of his earliest acclaimed paintings was The Moorland (Dewar Stone, Dartmoor), exhibited in 1854. This work, like many of his landscapes, showcases an intense focus on the foreground, with every blade of grass, frond of bracken, and texture of rock rendered with painstaking care. The painting conveys not just the visual appearance of the moor, but also its atmosphere and the intricate ecology of its plant life.

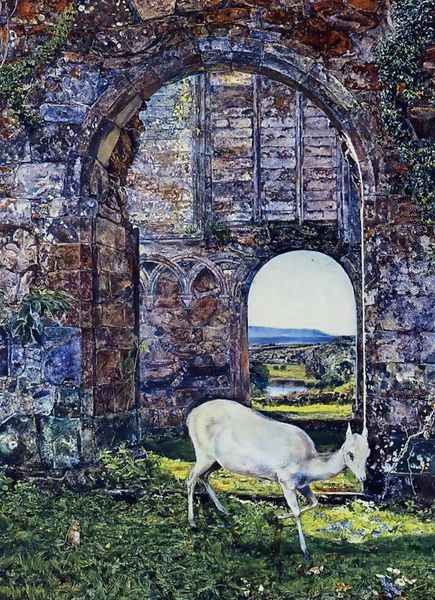

Perhaps his most famous early work, and one directly linked to Ruskin, is At Bolton (Bolton Abbey), also known as A Study, in March, completed around 1853. This painting depicts the ruins of Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire, a subject rich in historical and literary associations. It was inspired by William Wordsworth's poem "The White Doe of Rylstone." Ruskin was so impressed by the painting's fidelity to nature and its poetic sentiment that he purchased it, though he also offered Inchbold detailed critiques, famously advising him on the rendering of natural forms. The work is characterized by its cool, clear light, its meticulous depiction of early spring foliage, and its overall sense of tranquil beauty.

Another significant painting from this period is Anstey's Cove, Devon (c. 1853-1854). This coastal scene, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, is a tour-de-force of detailed observation. The geological strata of the cliffs, the varied textures of pebbles on the beach, the translucent quality of the water, and the delicate rendering of wildflowers are all captured with astonishing precision. The bright, clear colours and the high viewpoint are typical of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting, inviting the viewer to scrutinize every element of the composition. Artists like John Brett also painted similar coastal scenes with exacting detail, reflecting a shared Pre-Raphaelite fascination with geology and botany.

Later in his career, Inchbold continued to produce remarkable landscapes, often informed by his travels. The Jungfrau from near Lauterbrunnen (c. 1857-1860), depicting the majestic Swiss peak, demonstrates his ability to apply his meticulous technique to grand and awe-inspiring subjects. The painting captures the crystalline clarity of the mountain air and the sublime beauty of the Alpine scenery. Works like Tintagel (1862), depicting the dramatic Cornish coastline, and Drifting (1883), a later, perhaps more atmospheric piece, further illustrate his enduring commitment to landscape. Springtime in Spain, near Gordella (1866-1869) shows his engagement with different climates and terrains during his travels abroad.

Travels and Inspirations: Broadening Horizons

Like many artists of his era, John William Inchbold was an inveterate traveller. His journeys provided him with fresh subjects and inspiration, allowing him to study diverse landscapes and atmospheric conditions. His travels were not merely for leisure; they were integral to his artistic practice, as he often sketched and painted directly from nature in the locations he visited.

Switzerland was a particularly important destination for Inchbold. He visited the Alps on several occasions, sometimes in the company of John Ruskin. These trips were formative, exposing him to the grandeur of Alpine scenery, which he translated into powerful and detailed paintings like The Jungfrau and On the Lake Thun. Ruskin, with his profound knowledge of Alpine geology and his passion for mountain landscapes, would have been an influential companion, guiding Inchbold's eye and encouraging his meticulous approach. It was during one such Swiss trip that John Brett, another landscape painter associated with Pre-Raphaelitism, noted the profound impact of observing Inchbold's painting process.

Cornwall, with its rugged coastline and dramatic scenery, also attracted Inchbold. He spent several months there, sometimes in the company of the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne. The wild beauty of the Cornish landscape provided ample material for his brush, resulting in works like Tintagel.

His travels extended further afield to Italy and Spain. These Mediterranean countries offered different palettes, light conditions, and types of vegetation, which Inchbold incorporated into his work. Springtime in Spain, near Gordella is a testament to his experiences in the Iberian Peninsula, showcasing his ability to adapt his style to capture the unique character of foreign landscapes. These journeys not only broadened his visual repertoire but also connected him with the wider European artistic and cultural scene.

A Solitary Figure: Relationships and Artistic Circles

Despite his association with the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the patronage of influential figures like Ruskin, John William Inchbold was often described as a solitary and somewhat reclusive individual. He was not known for being particularly gregarious or adept at navigating the social intricacies of the London art world. This temperament may have contributed to a sense of isolation and, at times, hindered his commercial success.

While he was connected to the core Pre-Raphaelite circle, which included luminaries such as William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Ford Madox Brown, Inchbold seems to have remained somewhat on the periphery. He shared their artistic ideals, particularly their commitment to "truth to nature," but perhaps not their more public-facing or socially engaged activities. His focus remained intensely on his personal vision and his direct engagement with the landscape.

His relationship with John Ruskin was undoubtedly the most significant artistic connection of his career. Ruskin's praise and patronage were invaluable, particularly in Inchbold's early years. However, Ruskin could also be a demanding and critical mentor, and their relationship, while generally supportive, likely had its complexities. Other artists who shared a similar detailed approach to landscape, influenced by Ruskin and Pre-Raphaelitism, included John Brett, who specialized in coastal and Alpine scenes, and Thomas Seddon, known for his meticulous Eastern landscapes. William Dyce, an older artist, also showed Pre-Raphaelite tendencies in his detailed landscapes.

Inchbold also cultivated friendships within literary circles. His association with the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne is well-documented, and they spent time together in Cornwall. He was also acquainted with other literary figures such as Robert Browning and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, indicating a mind attuned to poetic as well as visual expression. This affinity for poetry is further evidenced by his own literary efforts. The Pre-Raphaelite movement itself had strong literary ties, with artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti being both a painter and a poet, and many Pre-Raphaelite paintings drawing inspiration from literature, including the works of Shakespeare, Keats, and Tennyson. Other artists associated with the broader Pre-Raphaelite circle included Edward Burne-Jones, known for his romantic and mythological subjects, Arthur Hughes, and the sculptor Thomas Woolner. James Collinson was an early member of the PRB, and Frederic George Stephens was both a painter and an influential art critic for the group. Alfred William Millais, brother of John Everett Millais, was also a painter.

Challenges, Later Years, and Poetic Pursuits

Despite the critical acclaim his work sometimes received and the support of patrons like Ruskin, John William Inchbold faced significant challenges throughout his career. His meticulous, time-consuming technique meant that his output was not prolific, and his paintings, often intensely detailed and demanding close attention, did not always find a ready market in an art world that was also embracing broader, more impressionistic styles.

His somewhat reclusive personality and perceived lack of sociability may have further complicated his professional life. He reportedly had a difficult relationship with the Royal Academy and other professional art institutions, which could be crucial for an artist's advancement and commercial success in the Victorian era. Consequently, Inchbold experienced periods of financial difficulty, with many of his paintings remaining unsold.

In his later years, Inchbold continued to paint, though his style may have evolved, perhaps showing a slightly broader handling in some works. He spent time living in various locations, reflecting his lifelong love of travel and his search for inspiring landscapes. He eventually settled in Headingley, a suburb of Leeds, his birthplace, where he spent his final years.

Beyond his painting, Inchbold also harbored literary ambitions. In 1877, he published a volume of poetry titled Annus Mirabilis: A Poem in the Alexandrine Stanza, which also included a sonnet sequence, "A Romantic Ode." This foray into poetry underscores the romantic and poetic sensibility that infused his visual art. His poems, like his paintings, often reflect a deep engagement with nature and a contemplative turn of mind.

John William Inchbold passed away in Headingley, Leeds, on January 23, 1888, at the age of 57. His death marked the end of a career dedicated to the pursuit of artistic truth, often in the face of considerable personal and professional challenges.

Legacy and Reappraisal

For a period after his death, John William Inchbold's work, like that of many Victorian artists, fell somewhat out of fashion as new artistic movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism came to dominate the art world. However, the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have seen a significant reappraisal of Victorian art, including the Pre-Raphaelite movement and its associated artists.

Inchbold is now recognized as one of the most gifted and distinctive landscape painters of the Pre-Raphaelite school. His unwavering commitment to detailed observation, his ability to capture the intricate beauty of the natural world, and the poetic intensity of his vision are increasingly appreciated. His work is seen as a vital contribution to the tradition of British landscape painting, standing alongside that of contemporaries like John Brett in its meticulous rendering of natural phenomena. His influence can also be discerned in the early works of artists like Atkinson Grimshaw, the Leeds-based painter known for his nocturnal urban scenes and moonlit landscapes, whose early style showed similarities to Inchbold's detailed approach.

Today, John William Inchbold's paintings are held in major public collections, including Tate Britain in London, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and various regional galleries such as the Leeds Art Gallery and the Northampton Museum and Art Gallery. Exhibitions featuring Pre-Raphaelite art regularly include his work, allowing new generations to discover his unique talent.

His life and art serve as a reminder of the dedication required to pursue a singular artistic vision. Though he may not have achieved widespread fame or fortune during his lifetime, John William Inchbold left behind a body of work that continues to captivate viewers with its exquisite detail, its vibrant colour, and its profound love for the natural world. He remains a testament to the enduring power of an artist who, in Ruskin's words, went to nature "in all singleness of heart."