Francesco Bassano the Younger, born Francesco Giambattista da Ponte in 1549, stands as a significant figure in the Venetian School of the Italian Renaissance. As the eldest son of the renowned painter Jacopo Bassano, Francesco was born into an artistic dynasty that left an indelible mark on 16th-century art. His life, though tragically cut short, was one of prolific creation, complex artistic development, and profound, if sometimes melancholic, introspection. Operating within the vibrant artistic milieu of Venice, Francesco inherited his father's keen observational skills and penchant for naturalism, while also forging his own path, subtly infusing his work with the elegant contortions of Mannerism and a distinctive approach to narrative and atmosphere.

Early Life and Artistic Apprenticeship in the Bassano Workshop

Francesco's artistic journey began in the bustling family workshop located in Bassano del Grappa, the town from which the family derived its name. Under the tutelage of his father, Jacopo Bassano (c. 1510–1592), a master in his own right, Francesco and his brothers—Giambattista (c. 1553–1613), Leandro (1557–1622), and Girolamo (1566–1621)—were immersed in the practice of painting from a young age. Jacopo was celebrated for his innovative approach to religious and genre scenes, often populating them with rustic figures, animals, and detailed depictions of everyday objects, all rendered with a vibrant palette and dynamic brushwork.

This environment was Francesco's crucible. He learned not only the technical aspects of painting—drawing, composition, color mixing, and the application of paint—but also the business of art. The Bassano workshop was a highly successful enterprise, producing a vast number of paintings for churches, private patrons, and the open market. Francesco quickly absorbed his father's style, demonstrating a precocious talent for capturing the textures of fabrics, the sheen of metal, and the lively expressions of human and animal subjects. His early works are often difficult to distinguish from those of Jacopo, a testament to his skill in emulating the paternal style and the collaborative nature of the workshop.

The influence of Jacopo was paramount. Jacopo himself had been influenced by a range of artists, including local Venetian masters and even Northern European printmakers like Albrecht Dürer, whose detailed naturalism found echoes in Jacopo's work. This eclectic foundation was passed on to Francesco, who would later build upon it with his own sensibilities.

The Move to Venice and Artistic Maturity

As Francesco matured as an artist, the family workshop's focus increasingly shifted towards Venice, the dominant artistic and commercial center of the region. Francesco eventually established himself in Venice, effectively becoming the workshop's representative in the city. This move was crucial for his development, exposing him to a wider range of artistic currents and a more sophisticated clientele. Venice was home to giants like Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), and Paolo Veronese, whose monumental compositions, dramatic use of light, and rich color palettes defined the Venetian High Renaissance.

While Francesco remained deeply rooted in the Bassano tradition, the Venetian atmosphere inevitably influenced his work. He began to incorporate elements of Mannerism, a style characterized by elongated figures, elegant and sometimes artificial poses, and a more subjective approach to color and space. This can be seen in the increased sophistication of his compositions and a certain refinement in his figures, moving slightly away from the more rustic earthiness of his father's earlier works. Artists like Parmigianino, whose graceful and elongated figures were hallmarks of Mannerism, may have provided stylistic touchstones.

Francesco's role in Venice also involved managing commissions and overseeing the production of works that often bore the Bassano family signature, indicating a collaborative effort. He was particularly adept at creating large-scale narrative paintings, often biblical or mythological in theme, which were popular among Venetian patrons.

Artistic Style: Naturalism, Mannerism, and the Bassano Touch

Francesco Bassano's style is a fascinating blend of inherited naturalism and acquired Mannerist elegance, all underpinned by the distinctive "Bassano touch"—a love for genre details, animals, and the depiction of everyday life, even within sacred or noble subjects.

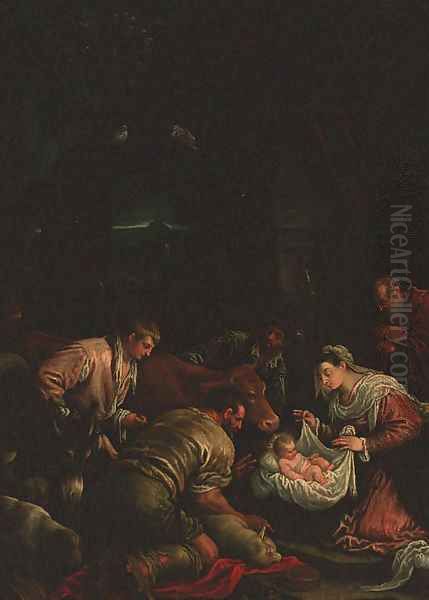

His father, Jacopo, was a pioneer in integrating genre elements into religious paintings. Scenes like the Adoration of the Shepherds or The Journey of Jacob were filled with peasants, livestock, and domestic objects, grounding the biblical narratives in a relatable, contemporary reality. Francesco continued this tradition with great skill. His paintings are often teeming with life: dogs, sheep, cattle, and birds are rendered with an affectionate accuracy, and his human figures, even in lofty scenes, possess a tangible humanity.

The influence of Mannerism is evident in Francesco's treatment of figures, which can be more elongated and gracefully posed than those of his father. His compositions sometimes feature more complex spatial arrangements and a heightened sense of drama, often achieved through dynamic lighting and rich, sometimes nocturnal, color schemes. He was particularly skilled in depicting night scenes, using chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) to create mood and focus attention. This interest in dramatic lighting prefigures some aspects of the later Baroque period, and artists like Caravaggio, who would master chiaroscuro, may have found inspiration in the Bassano workshop's experiments with light.

Francesco's palette was rich and varied, capable of capturing both the earthy tones of rural life and the more sumptuous colors favored in Venetian painting. His brushwork was often lively and descriptive, imbuing his surfaces with texture and vitality. He also frequently collaborated with his brothers, particularly Leandro, and distinguishing their individual hands in workshop productions can be challenging for art historians.

Key Themes and Subjects in Francesco's Oeuvre

Francesco Bassano's body of work encompasses a range of themes, reflecting the demands of his patrons and the artistic interests of the time.

Religious Narratives:

Biblical scenes formed a significant portion of his output. He painted numerous versions of subjects like The Last Supper, The Adoration of the Shepherds, The Adoration of the Magi, Christ Driving the Merchants from the Temple, and Christ in the Garden of Olives. These works often followed the Bassano family tradition of incorporating numerous figures, animals, and still-life details, making the sacred stories accessible and visually engaging. His Last Supper compositions, for instance, often include domestic details like servants, dogs, and kitchenware, creating a bustling, almost genre-like atmosphere around the solemn event.

Genre Scenes and Rural Life:

While often embedded within religious narratives, Francesco also produced works that focused more explicitly on rural life and seasonal activities. The Bassano workshop was famous for its series depicting the Four Seasons, often allegorically linked to biblical stories or mythological themes. For example, Autumn, with Moses Receiving the Ten Commandments combines a depiction of the harvest season with a significant Old Testament event. These paintings celebrate the bounty of nature and the labors of peasant life, rendered with a characteristic vibrancy and attention to detail that would resonate with later genre painters like those of the Dutch Golden Age, such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who also depicted peasant life with great empathy.

Mythological and Allegorical Compositions:

Francesco also tackled mythological subjects, drawing from classical literature. These works allowed for a different kind of narrative expression, often involving dynamic action and the depiction of the nude or semi-nude figure, though always treated with a certain Venetian decorum. Allegorical paintings, such as personifications of the elements or virtues, were also part of his repertoire, reflecting the intellectual tastes of some of his patrons.

Historical Paintings and State Commissions:

A significant achievement in Francesco's career was his participation in the redecoration of the Doge's Palace in Venice after fires in 1574 and 1577. He contributed several large-scale historical paintings, including scenes of Venetian military victories. These commissions placed him alongside the leading artists of Venice, such as Tintoretto and Veronese, and demonstrated his ability to work on a grand, official scale. His Battle of Lepanto is a notable example of his work in this prestigious venue.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Francesco Bassano's skill and artistic concerns:

<em>The Last Supper</em> (various versions): Francesco, like his father and brothers, painted this subject multiple times. A version in the Prado Museum, Madrid, showcases the typical Bassano approach: a dynamic composition, rich colors, expressive figures, and an abundance of genre details, including animals and household items, that animate the scene. The lighting is often dramatic, highlighting Christ and the apostles amidst the surrounding activity.

<em>The Adoration of the Shepherds</em> (various versions): This was another favorite theme for the Bassano workshop. Francesco's interpretations are characterized by a tender naturalism, with humble shepherds and their families adoring the Christ Child in a rustic setting, often illuminated by a divine light that pierces the nocturnal gloom. The inclusion of meticulously rendered animals and everyday objects adds to the scene's charm and relatability.

<em>Christ in the Garden of Olives</em>: This subject allowed Francesco to explore themes of suffering and divine communion, often set within a dramatic, moonlit landscape. The emotional intensity of Christ's prayer is contrasted with the sleeping disciples, a composition that lends itself to expressive lighting and poignant characterization.

<em>Autumn, with Moses Receiving the Ten Commandments</em> (e.g., version in the National Gallery, London): Part of a series on the Seasons, this painting exemplifies the Bassano workshop's ability to blend genre with religious narrative. The foreground is filled with figures engaged in autumnal activities like grape harvesting, while in the background, Moses receives the tablets on Mount Sinai. The painting is a rich tapestry of rural life, rendered with vibrant colors and a keen eye for detail.

<em>The Element of Fire</em> or <em>Vulcan's Forge</em> (e.g., version in the Ringling Museum of Art): This mythological subject, often depicted as part of a series on the Four Elements, allowed Francesco to showcase his skill in depicting muscular male figures, the glow of the forge, and the textures of metalwork. These paintings often have a dynamic energy and a dramatic use of light emanating from the fire.

<em>Christ in the House of Mary and Martha</em>: This biblical story, which contrasts active service with contemplative devotion, was another subject Francesco treated. His versions typically depict a busy household scene, with Martha engaged in domestic tasks while Mary listens to Christ, allowing for a rich interplay of figures and activities.

Collaborations and the Bassano Workshop's Production

The Bassano workshop operated as a highly efficient and collaborative enterprise. Francesco worked closely with his father and his brothers, particularly Leandro. It was common for multiple versions of successful compositions to be produced, with different family members contributing according to their strengths. This collaborative nature means that attributions can sometimes be complex, with works often signed "Bassano" or attributed to the "Bassano workshop."

Francesco, as the eldest son and manager of the Venetian branch, played a crucial role in maintaining the workshop's productivity and reputation. He was skilled at adapting his father's compositions and creating new variations that appealed to contemporary tastes. The workshop's output was prodigious, and their paintings were widely collected throughout Italy and Europe. This system of production, while ensuring commercial success, sometimes led to a degree of repetition in their themes and compositions, though often with subtle variations that kept the works fresh.

The influence of other Venetian masters like Tintoretto, with his dramatic compositions and flickering light, and Veronese, with his opulent color and grand narratives, can be discerned in Francesco's work, particularly in his larger-scale commissions. However, he always retained the core Bassano characteristics of naturalism and a focus on the tangible details of the world.

Later Years, Psychological Struggles, and Tragic End

Despite his artistic success, Francesco Bassano's later years were marked by personal turmoil. After his father Jacopo's death in February 1592, the responsibility for the family workshop largely fell on Francesco and his brother Leandro. Francesco, however, reportedly suffered from periods of deep depression and melancholy. Contemporary accounts, including those by the art historian Carlo Ridolfi, suggest that he was prone to hypochondria and perhaps a persecution complex.

The pressures of managing the workshop, coupled with his underlying psychological fragility and possibly physical illness (some sources mention tuberculosis), took a heavy toll. In a tragic turn of events, Francesco Bassano died by suicide in July 1592, only a few months after his father. He reportedly threw himself from a window of his house in Venice. He was only 43 years old.

His untimely death was a significant loss to the Venetian art world and to the Bassano family. His brother Leandro da Ponte, who was also a highly accomplished painter and had been knighted, continued to lead the workshop and uphold the family's artistic legacy, often working in a style that, while rooted in the Bassano tradition, developed its own distinct characteristics, including a more polished finish and a focus on portraiture.

Legacy and Influence on Later Art

Francesco Bassano the Younger, despite his relatively short life, made a lasting contribution to Venetian painting and influenced subsequent generations of artists. His adherence to naturalism, his skill in depicting genre scenes and animals, and his atmospheric use of light were particularly impactful.

The Bassano family's emphasis on everyday life and rustic themes, in which Francesco played a key role, helped to popularize genre painting in Italy. This interest in the ordinary, often infused with a warm humanity, can be seen as a precursor to the more developed genre traditions of the 17th century, particularly in the Netherlands with artists like Adriaen Brouwer or David Teniers the Younger, and in Italy itself.

His dramatic use of chiaroscuro, especially in night scenes, contributed to a broader exploration of light and shadow in painting. While Titian had explored nocturnal scenes and Tintoretto had used dramatic lighting for expressive effect, the Bassanos, including Francesco, made it a recurring feature of their work. This preoccupation with light effects would be taken to new heights by Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti), such as Artemisia Gentileschi or Jusepe de Ribera, who used tenebrism (a dramatic form of chiaroscuro) to create powerful and emotionally charged paintings.

The Bassano workshop's prolific output ensured that their works were widely disseminated, spreading their style and thematic innovations. Even if specific influences are hard to trace directly, the general Bassano approach—its blend of religious sentiment with everyday reality, its love of nature, and its vibrant depiction of life—resonated with many artists and patrons. Francesco's role in refining and popularizing this approach, particularly in the sophisticated urban environment of Venice, was crucial.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Francesco Bassano the Younger was an artist shaped by a powerful family tradition yet possessed of his own distinct voice. He successfully navigated the demands of a thriving workshop, the expectations of diverse patrons, and the rich artistic currents of late 16th-century Venice. His paintings, characterized by their lively naturalism, detailed observation, rich color, and often dramatic lighting, capture a world where the sacred and the profane, the rustic and the refined, coexist.

While his life was overshadowed by psychological struggles and ended in tragedy, his artistic legacy endures. Through his numerous works, many of which grace major museums and collections worldwide, Francesco Bassano the Younger continues to engage viewers with his vibrant depictions of biblical narratives, mythological tales, and the enduring rhythms of life. He remains a testament to the artistic vitality of the Bassano dynasty and a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Venetian Renaissance art, whose influence subtly permeated the artistic developments that followed.