Lelio Orsi, also known as Lelio da Novellara, stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 16th-century Italian art. Born in Novellara around 1508 or 1511 and dying there in 1587, Orsi was a versatile artist, active primarily as a painter and architect in the Emilia region. His career, marked by periods of intense creativity, unfortunate personal circumstances, and a distinctive artistic style, places him as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, proponent of Mannerism. His work synthesized the grace of Correggio, the muscular energy of Michelangelo, and the complex dynamism of Giulio Romano, forging a personal idiom characterized by dramatic lighting, intricate compositions, and profound emotional depth.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Lelio Orsi's artistic journey began in his hometown of Novellara, a small lordship then ruled by the Gonzaga family. It is believed he received his initial training from his father, Giovanni Orsi, who was also a painter, though little is known about his work. The artistic environment of Emilia was rich and vibrant, dominated by the towering legacy of Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (c. 1489–1534). Correggio's revolutionary use of sfumato, his tender depictions of religious and mythological scenes, and his breathtaking illusionistic dome frescoes in Parma, such as those in the Cathedral and San Giovanni Evangelista, left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of Emilian artists, including Orsi.

Another pivotal influence on Orsi was Giulio Romano (c. 1499–1546), Raphael's principal pupil and a leading figure of Mannerism. Romano's work in Mantua, particularly the frescoes in the Palazzo del Te, with their powerful, often contorted figures, complex narratives, and architectural fantasies, provided a compelling model for artists seeking to move beyond the High Renaissance ideals of harmony and balance. Orsi clearly absorbed Romano's penchant for dynamic compositions and expressive figural language.

The broader artistic currents of the time also shaped Orsi. The High Renaissance, with masters like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and the aforementioned Michelangelo, had set unparalleled standards. However, by the 1520s, a new style, Mannerism, began to emerge, characterized by elongation of forms, stylized elegance, intricate compositions, and often unsettling emotional content. Artists like Parmigianino (1503–1540), another Emilian genius profoundly influenced by Correggio but who pushed his style towards greater artifice and sophistication, would have been a contemporary whose work Orsi undoubtedly knew. Other Mannerists active in Central Italy, such as Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, were also redefining artistic expression.

The Roman Experience and Michelangelesque Impact

A crucial period in Orsi's development was his time spent in Rome. While the exact dates are debated, it's generally accepted that he was in the Eternal City at least between 1554 and 1555, and possibly earlier. Rome was the epicenter of artistic innovation, and for Orsi, the encounter with the works of Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) was transformative. Michelangelo's powerful figures in the Sistine Chapel ceiling and, particularly, the dynamic, swirling forms of the Last Judgment (completed 1541), with its terribilità (awesomeness or sublime terror), deeply resonated with Orsi. He absorbed Michelangelo's anatomical understanding, his dramatic use of foreshortening, and the sheer expressive force of his figures.

During his Roman sojourn, Orsi would also have encountered the works of other prominent artists. Raphael's Stanze in the Vatican and the elegant classicism of his later works continued to be influential. The followers of Raphael, such as Perino del Vaga, and other Mannerist decorators like Daniele da Volterra (a close follower of Michelangelo) and the Zuccaro brothers, Taddeo and Federico, were actively shaping the artistic landscape of Rome with large-scale fresco cycles. Orsi's exposure to this environment undoubtedly refined his skills and broadened his artistic vocabulary, particularly in decorative schemes and the integration of figures within complex architectural settings.

Career in Reggio Emilia and the Unfortunate Interruption

Upon returning from Rome, Orsi became highly active in Reggio Emilia, a larger artistic center than Novellara. Here, he undertook numerous commissions for paintings and facade decorations. His reputation grew, and he was recognized for his unique ability to blend Correggiesque softness with Michelangelesque power and Mannerist complexity. His works from this period likely included ambitious fresco cycles and altarpieces, showcasing his mature style.

However, Orsi's flourishing career in Reggio Emilia was abruptly cut short by a dark and unfortunate event. Around 1546 (though some sources suggest this occurred later, leading to his definitive return to Novellara after his Roman stay), he became implicated in a murder or a serious affray. The exact details of this incident remain obscure, but the consequences were severe. To escape justice or retribution, Orsi was forced to flee Reggio Emilia and return to his native Novellara. This event had a profound impact on his career; he lost his standing in Reggio, and many of the works he created there were subsequently lost, destroyed, or have not survived, contributing to the challenges in fully assessing his oeuvre from this period.

Return to Novellara: A Prolific Period

Despite the setback, Lelio Orsi found patronage and continued his artistic activities in Novellara under the protection of the Gonzaga lords, particularly Alfonso I Gonzaga. He spent the remainder of his life there, from roughly the mid-1550s until his death in 1587. This period was remarkably productive, with Orsi focusing on a wide range of projects, including paintings, extensive facade decorations, and architectural designs.

In Novellara, Orsi became the court artist, and his talents were employed to enhance the prestige and beauty of the small state. He designed numerous illusionistic facade paintings for palaces and public buildings, a popular form of decoration at the time that transformed urban spaces into vibrant theatrical settings. These works, often executed in fresco or sgraffito, were ephemeral by nature and, sadly, most have perished or survive only in fragments or preparatory drawings. His designs for the Palazzo Comunale (Town Hall) and the Rocca di Novellara (the Gonzaga castle), including rooms like the Sala del Fico and Sala del Cardinale, showcased his skill in creating grand decorative ensembles. He was also reportedly involved in a project initiated by Alfonso Gonzaga in 1563 to restore and decorate the plaster facades throughout the city.

His architectural work also came to the fore during this period. While primarily a painter, Orsi possessed a keen understanding of architectural principles, likely honed by his study of Roman antiquities and contemporary architectural theory, perhaps through treatises by architects like Sebastiano Serlio or Andrea Palladio.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Despite the loss of many larger commissions, a significant body of Lelio Orsi's work survives, primarily in the form of smaller cabinet paintings, altarpieces, and numerous drawings, which attest to his skill and originality.

The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine (c. 1560; Galleria Estense, Modena) is one of his most celebrated paintings. This dramatic work depicts the saint at the moment the spiked wheel of her intended execution miraculously shatters. Orsi's composition is dynamic and crowded, with muscular figures in contorted poses reminiscent of both Michelangelo and Giulio Romano. The lighting is stark and theatrical, highlighting the saint's serene faith amidst the chaos and the divine intervention. The intensity of emotion and the swirling energy are characteristic of his mature style.

The Walk to Emmaus (also known as Christ's Resurrection from Luke, c. 1565-1575; National Gallery, London) is another key work. It portrays the resurrected Christ appearing to two disciples. Orsi infuses the scene with a sense of mystery and divine revelation. The figures are robust, and the landscape is rendered with a dramatic, almost visionary quality. The play of light and shadow, particularly the way Christ is illuminated, emphasizes the spiritual significance of the moment. A preparatory drawing for this composition is also known, highlighting his meticulous approach.

Noli Me Tangere (c. 1575; Galleria Estense, Modena) depicts the moment when the resurrected Christ tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him. Orsi captures the emotional intensity of the encounter, with Christ's gentle restraint and Mary's yearning. The figures are elegant and elongated, typical of Mannerist aesthetics, and the landscape is imbued with a mystical atmosphere. A related drawing is housed in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford.

The Dead Christ Flanked by Charity and Justice (c. 1570; Galleria Estense, Modena) is a poignant and powerful image. The sculptural quality of Christ's body shows Michelangelo's influence, while the allegorical figures display a Mannerist grace. The somber palette and dramatic lighting contribute to the work's devotional intensity.

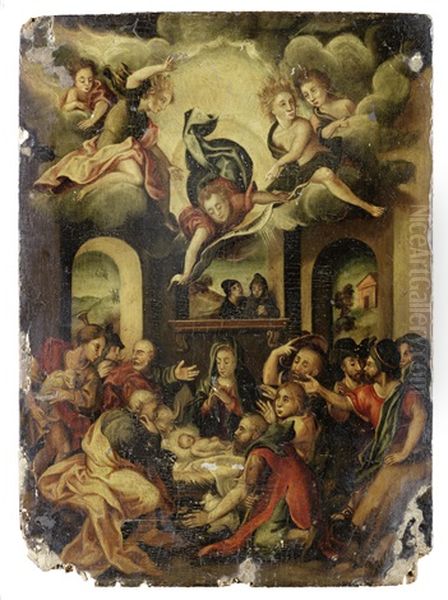

The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1575; Galleria Estense, Modena, with another version in the Hercolani Collection, Bologna) showcases Orsi's ability to handle complex group compositions and to create a sense of wonder and reverence. The influence of Correggio's nocturnal scenes can be felt in the dramatic use of light emanating from the Christ Child.

His drawings, such as Apollo Driving the Chariot of the Sun (Louvre, Paris), reveal his mastery of line, his dynamic sense of movement, and his imaginative power. Many of these drawings were highly finished and were likely intended as independent works of art or as detailed studies for larger, now-lost compositions. They often feature mythological or allegorical subjects, rendered with a characteristic energy and refinement.

Architectural Achievements: The Collegiata di San Stefano

Lelio Orsi's most significant surviving architectural achievement is the design for the Collegiata di San Stefano (Collegiate Church of St. Stephen) in Novellara. Construction began in 1567, though the building was completed after his death, with some modifications to his original plans. Orsi's design, known in part through a drawing preserved in the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, envisioned a church with a classical facade and a well-proportioned interior. It reflects his understanding of Renaissance architectural principles, possibly influenced by contemporary architects like Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola. The church stands as a testament to his versatility and his ability to translate his artistic vision into three-dimensional form.

He also designed other structures in Novellara, including the Casino di Sotto and Casino di Sopra, private residences for the Gonzaga family, which likely featured elaborate painted facades and interior decorations. These projects demonstrate his role in shaping the architectural and visual character of Novellara during his tenure as court artist.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Power and Grace

Lelio Orsi's artistic style is a complex and highly personal synthesis of various influences, firmly rooted in the Mannerist tradition of Emilia. Key characteristics include:

Dynamic Compositions: His paintings and drawings are often filled with figures in motion, arranged in complex, sometimes swirling, patterns. He avoided static or purely symmetrical arrangements, preferring asymmetry and a sense of energetic movement.

Muscular and Elongated Figures: Orsi's figures often combine the anatomical power and muscularity derived from Michelangelo with the elongated proportions and graceful, sometimes contorted, poses characteristic of Mannerism, as seen in the work of Parmigianino or Beccafumi.

Dramatic Chiaroscuro: He was a master of light and shadow, using strong contrasts (chiaroscuro) to model forms, create dramatic emphasis, and imbue his scenes with emotional intensity. This can be seen as a development of Correggio's sfumato, pushed towards greater theatricality, and it prefigures some of the dramatic lighting effects that would become prominent in the Baroque period with artists like Caravaggio (though direct influence from Caravaggio on Orsi is chronologically impossible, they shared an interest in expressive light, possibly drawing from earlier North Italian traditions seen in artists like Savoldo or Lotto).

Intense Emotional Expression: Orsi's figures are rarely impassive. He conveyed a wide range of emotions, from serene piety and divine ecstasy to anguish and turmoil, often with a heightened, theatrical sensibility.

Rich and Sometimes Unusual Color Palettes: While sometimes employing somber tones for dramatic effect, Orsi could also use vibrant and unexpected color combinations, a hallmark of many Mannerist painters.

Imaginative and Visionary Quality: Many of his works, particularly his drawings of mythological and allegorical subjects, possess a dreamlike, visionary quality. He excelled at creating fantastical scenes and imbuing them with a sense of otherworldly energy.

Decorative Flair: A significant portion of Orsi's output involved decorative schemes for facades and interiors. This required a strong sense of design, an ability to integrate figures and ornament, and an understanding of illusionistic techniques to create captivating visual effects. Artists like Niccolò dell'Abate, another Emilian who also excelled in decorative frescoes before moving to France, worked in a similar vein.

Orsi's style was distinct from the more classical and naturalistic trends that were also present in the 16th century. He embraced the artifice, complexity, and expressive potential of Mannerism, creating works that were both intellectually stimulating and visually compelling.

Legacy and Later Appreciation

Lelio Orsi's reputation suffered somewhat due to the loss of many of his large-scale works and the relative isolation of Novellara compared to major artistic centers like Florence, Rome, or Venice. For a long time, he was considered a provincial master, albeit a highly talented one. However, scholarly research in the 20th and 21st centuries has led to a greater appreciation of his originality and his significant contribution to Emilian Mannerism.

His surviving paintings and, especially, his numerous drawings are now highly prized by collectors and museums. Institutions such as the Galleria Estense in Modena, the Louvre in Paris, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, the Gonzaga Museum in Novellara, and the Ca' Rezzonico Museum in Venice hold important examples of his work. His drawings, in particular, have been the subject of exhibitions, such as those in New York and at the Art Institute of Chicago, which have helped to highlight his exceptional skill as a draftsman and his fertile imagination.

Orsi's influence on subsequent artists in the Emilia region is discernible, though perhaps not as widespread as that of Correggio or Parmigianino. He represents a unique strand of Mannerism, one that combined local Emilian traditions with the powerful influences of Central Italian art, particularly that of Michelangelo. His dramatic use of light and his expressive intensity can be seen as anticipating certain aspects of Baroque art.

The story of Lelio Orsi is one of immense talent navigating the complexities of artistic influence, personal misfortune, and the demands of patronage. He was an artist who, despite periods of adversity, continued to produce works of remarkable power, beauty, and originality. His ability to synthesize diverse artistic currents into a coherent and personal style, his mastery of both painting and architectural design, and the sheer imaginative force of his creations secure his place as a significant master of the Italian Renaissance, a testament to the enduring creativity found even beyond the most celebrated artistic hubs. His legacy is a reminder of the rich tapestry of regional artistic schools that flourished in Italy and contributed to the magnificent diversity of Renaissance and Mannerist art.