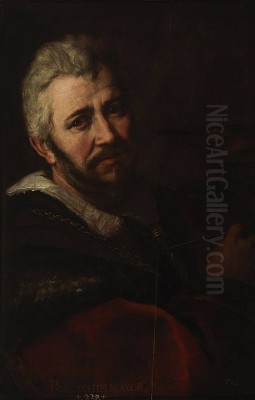

Giulio Cesare Procaccini stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from late Mannerism to the burgeoning Baroque style in Lombardy. Born in Bologna in 1574, he was immersed in an artistic environment from birth. His father, Ercole Procaccini the Elder, was a respected painter, and his older brothers, Camillo and Carlo Antonio, would also become notable artists. This familial connection to the arts provided a foundation for Giulio Cesare's own prodigious talents, which would flourish primarily in Milan, the city his family relocated to around 1587. His career trajectory, moving from sculpture to painting, and his unique synthesis of diverse artistic influences, mark him as a key protagonist in the vibrant Milanese art scene of the early 17th century.

From Chisel to Brush: Early Life and Sculptural Beginnings

The Procaccini family's move to Milan placed them in a major artistic center undergoing significant development, partly fueled by the Counter-Reformation directives of figures like Cardinal Federico Borromeo. Initially, Giulio Cesare followed a path distinct from his father and painter brother Camillo. He trained and began his professional career as a sculptor, a field where he quickly gained recognition. His skills were employed in prestigious projects, most notably contributing decorative sculptures to the Duomo (Milan Cathedral) and the facade of the Basilica di Santa Maria presso San Celso, another significant Milanese church. This early work in three dimensions likely informed his later approach to painting, particularly in his handling of form, volume, and the dynamic interplay of figures in space. His sculptural work demonstrated technical proficiency and an understanding of anatomical representation, skills that would translate effectively onto the canvas.

The Transition to Painting and Defining Influences

Around the turn of the 17th century, Procaccini made a decisive shift towards painting, the medium in which he would achieve his greatest fame. This transition wasn't abrupt but rather a refocusing of his artistic energies. His initial paintings reveal a complex blend of influences. Naturally, the artistic traditions of his native Bologna, particularly the late Mannerist elegance and sophisticated compositions seen in the works of artists like the Carracci family (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico Carracci), played a role. However, Procaccini looked further afield. The rich colors, dramatic lighting, and emotional intensity of Venetian masters such as Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese clearly captivated him, infusing his work with a chromatic vibrancy often absent in Lombard tradition. Furthermore, the profound influence of artists from Parma, especially the sensuous grace and emotional tenderness of Correggio and the stylish elongation and complex spatial arrangements of Parmigianino, became deeply ingrained in his style. This eclectic mix formed the basis of his unique artistic voice.

Forging a Milanese Baroque Style

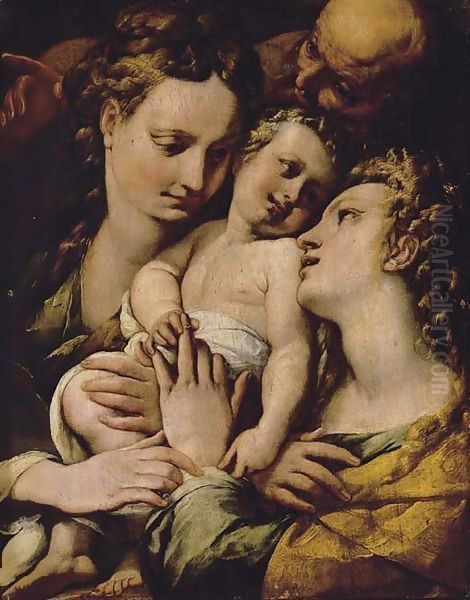

Procaccini rapidly developed a distinctive style that became central to the Milanese Early Baroque. His paintings are characterized by their dynamic compositions, often featuring swirling movement and complex groupings of figures. He possessed a remarkable ability to convey intense emotion, ranging from ecstatic religious fervor to profound suffering, through expressive faces and dramatic gestures. His use of chiaroscuro, the dramatic contrast between light and shadow, was masterful, heightening the theatricality of his scenes and focusing the viewer's attention. Unlike the starker realism sometimes found in Lombard art (influenced by Caravaggio), Procaccini's figures often retain an elegance and grace derived from his Mannerist and Emilian influences, but imbued with a new level of Baroque energy and psychological depth. His color palette remained rich, often employing jewel-like tones that added to the visual splendor of his works.

Major Commissions and Representative Works

Procaccini's talent quickly attracted significant patronage from both ecclesiastical and private clients in Milan and beyond. One of his most important collaborative projects was the series of large canvases depicting miracles from the life of Saint Charles Borromeo, known as the Quadroni di San Carlo Borromeo, created for the Milan Cathedral around 1610. He worked alongside the other two leading lights of Milanese painting at the time: Giovanni Battista Crespi, known as Il Cerano, and Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, called Il Morazzone. This project cemented their status as the dominant figures in the city's art scene.

Procaccini produced numerous altarpieces and devotional paintings. Among his celebrated works is The Last Supper (1618), housed in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata del Vastato in Genoa, a powerful interpretation of the subject showcasing his dynamic composition and emotional intensity. Another significant work in Genoa is The Circumcision, located in the Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta di Carignano, noted for its rich color and complex figural arrangement. His depictions of martyrdoms, such as the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (found in the Harvard Art Museums), allowed him to explore themes of suffering and faith with dramatic flair. Works like The Holy Family with the Infant John the Baptist and an Angel (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) demonstrate his ability to handle tender, intimate subjects with grace and warmth. Themes like The Annunciation and depictions of the Madonna and Saints were recurrent, allowing for variations in composition and emotional expression. A notable Flagellation of Christ, showcasing his dramatic use of light and depiction of suffering, can be found in the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The Procaccini Dynasty: Family and Workshop

Artistic production in this era often involved family workshops, and the Procaccinis were no exception. Giulio Cesare worked within a network that included his father, Ercole the Elder, and his brothers. His older brother, Camillo Procaccini (c. 1551–1629), was already an established painter upon the family's arrival in Milan, known for his large-scale decorative schemes. While distinct artists, Giulio Cesare and Camillo likely operated in the same circles, potentially sharing patrons and occasionally influencing each other, though a degree of professional rivalry in securing commissions is also plausible within the competitive Milanese environment.

Giulio Cesare's younger brother, Carlo Antonio Procaccini (1571–1630), frequently collaborated with him. Carlo Antonio specialized more in landscape and still life elements, particularly floral arrangements, which sometimes feature in Giulio Cesare's larger compositions. A famous example of collaboration, involving not only Giulio Cesare and Carlo Antonio but also Morazzone, is the Martyrdom of Saints Rufina and Secunda, sometimes referred to as the Quadro delle tre mani (Painting of the Three Hands), now housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. This collaboration highlights the fluid boundaries within workshops and among leading artists of the time. Attribution questions sometimes arise, with certain works potentially being joint efforts or occasionally misattributed between the brothers.

Collaboration and Context: Milanese Contemporaries

The Milanese art scene during Procaccini's career was particularly vibrant, fostered by patrons like Cardinal Federico Borromeo, who founded the Ambrosiana Library and Picture Gallery. Procaccini's frequent collaborators, Il Cerano (Giovanni Battista Crespi) and Il Morazzone (Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli), were his main artistic peers and rivals. Cerano was known for his intense, often somber piety and dramatic realism, while Morazzone displayed a vigorous style with strong contrasts of light and color. Their joint work on the Quadroni exemplifies the collaborative spirit, yet each maintained a distinct artistic personality.

Other significant artists active in Lombardy during this period provide further context. Daniele Crespi, a gifted pupil of Cerano who tragically died young in the plague of 1630, absorbed influences from all three masters, including Procaccini, developing a powerful, direct style. Tanzio da Varallo brought a unique, somewhat eccentric realism and intensity to his religious subjects, representing a different facet of Lombard art. The period also saw the rise of still life painting as an independent genre, with Fede Galizia being a notable early pioneer, alongside figures like Panfilo Nuvolone. While Procaccini focused on figurative and religious subjects, the presence of these diverse talents enriched the artistic milieu in which he worked.

The Impact of Rubens and Later Developments

A significant development in Procaccini's later style came after a trip to Genoa around 1618. Genoa was a wealthy port city with sophisticated patrons who collected art from across Europe. There, Procaccini encountered the works of Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish Baroque master who had spent several years in Italy. Rubens' dynamic compositions, rich color, energetic brushwork, and robust figures made a profound impact on Procaccini. His subsequent works often show a looser, more painterly handling, a brighter palette, and an even greater sense of movement and vitality, reflecting his absorption of Rubens' powerful Baroque language. This assimilation of Flemish influences added another layer to his already complex style.

Beyond Painting: Sculpture and Graphic Works

Although painting became his primary focus, Procaccini never entirely abandoned his sculptural roots. His understanding of form, honed through sculpture, remained evident in the solidity and three-dimensionality of his painted figures. He also ventured into the realm of printmaking, producing a small number of etchings. These graphic works are rare today, with only a couple considered autograph. While perhaps not reaching the technical perfection of dedicated printmakers, his etchings display a painterly quality and explore dramatic compositions, offering insight into his creative process and his experimentation across different artistic media. They reflect the broader Baroque interest in the expressive potential of etching, practiced by contemporaries like Guido Reni and Jusepe de Ribera.

Patronage, Anecdotes, and Reputation

Procaccini enjoyed considerable success, securing commissions from prominent Milanese families, religious orders, and patrons in other cities like Genoa. The patronage of Cardinal Federico Borromeo was particularly important, providing opportunities for major public commissions. The connection with Genoese patrons, such as the influential Doria family (including the collector Giovan Battista Doria Carlo), was crucial for his later career and exposure to artists like Rubens. Anecdotes, like the story of the Tre Mani collaboration, illustrate the working practices of the time. The occasional uncertainty in attributions between Giulio Cesare and his brother Carlo Antonio also speaks to the collaborative nature of their workshop and the similarities in their handling of certain elements. Throughout his career, Procaccini was recognized as one of Milan's leading artistic talents.

Legacy and Position in Art History

Giulio Cesare Procaccini died in Milan in 1625. He left behind a significant body of work that firmly places him as a key figure in the development of the Baroque style in Lombardy. He successfully navigated the transition from the elegance of late Mannerism to the drama and emotional intensity of the Baroque. His unique synthesis of influences – Bolognese structure, Venetian color, Emilian grace, and later, Flemish dynamism – created a style that was both sophisticated and powerfully expressive. He, along with Cerano and Morazzone, defined the character of Milanese painting in the early 17th century. His work influenced subsequent generations of Lombard artists, contributing to the region's distinct artistic identity within the broader Italian Baroque landscape. He is remembered as a versatile artist, skilled in sculpture, painting, and etching, whose works continue to impress with their technical brilliance, emotional depth, and dramatic power.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Giulio Cesare Procaccini remains a vital figure for understanding the complexities of Italian art in the early 17th century. More than just a regional master, he engaged with the major artistic currents of his time, forging a personal style that was both innovative and deeply rooted in tradition. His ability to blend grace with drama, vibrant color with emotional intensity, and sculptural form with painterly energy marks him as a master of the Early Baroque. His collaborations, his role within a prominent artistic family, and his response to influential figures like Correggio and Rubens paint a picture of a dynamic artist fully engaged with the rich artistic world around him. His legacy endures in the powerful altarpieces and devotional paintings that still adorn churches and galleries, testaments to his skill and his significant contribution to the visual culture of the Baroque era.