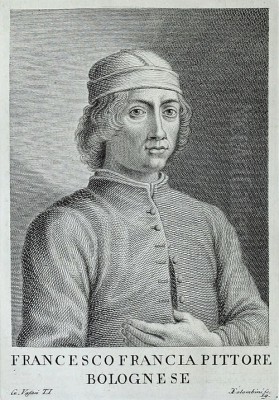

Francesco Francia, born Francesco di Marco di Giacomo Raibolini around 1447-1450 and passing away in 1517, stands as a pivotal figure in the artistic landscape of Bologna during the Italian Renaissance. Initially trained and highly esteemed as a goldsmith, Francia later transitioned to painting, where he became the leading master of the Bolognese school in his time. His art, characterized by its gentle piety, refined execution, and sweet expressions, reflects a synthesis of local traditions and the burgeoning ideals of the High Renaissance emanating from artistic powerhouses like Florence and Rome. This exploration delves into the life, works, influences, and legacy of an artist who, while perhaps not reaching the universal fame of contemporaries like Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, carved a significant niche for himself and left an indelible mark on the art of his region.

From Goldsmith's Bench to Painter's Easel: The Early Years

Francesco Francia's story begins in Bologna, a city with a rich cultural and intellectual heritage, home to one of Europe's oldest universities. Born into what is believed to be an artisan family, his early inclinations led him to the meticulous craft of goldsmithing. This was not an uncommon path for Renaissance artists; figures like Filippo Brunelleschi, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Andrea del Verrocchio also had roots in metalwork, a discipline that demanded precision, an understanding of form, and decorative finesse.

Francia excelled in this field. By 1482, he is documented as a member of the goldsmiths' guild in Bologna, and his skill was such that he rose to become the guild's master (massaro) on multiple occasions, a testament to the high regard in which his peers held him. His reputation extended to the mint, where he served as a die-cutter for the Bolognese coinage under the Bentivoglio family, the city's de facto rulers, and later under Pope Julius II. His work in niello, a black metallic alloy used for inlaying engraved metal, was particularly praised, as was his skill in crafting intricate medals and other precious objects. These early experiences in goldsmithing undoubtedly honed his eye for detail, his steady hand, and his appreciation for refined surfaces, qualities that would later manifest in his paintings. The precision required for engraving and casting metal translated into a careful, almost polished, rendering of form and texture in his painted works.

The exact moment or reason for Francia's transition to painting is not definitively known, but it likely occurred in the 1480s. It was a period when Bologna was experiencing a flourishing of the arts, partly due to the patronage of the Bentivoglio family. The city, while having its own artistic traditions, was also receptive to influences from nearby Ferrara, with its distinctive school led by artists like Cosimo Tura, Francesco del Cossa, and Ercole de' Roberti, as well as from Central Italy.

The Bolognese Artistic Milieu and Key Influences

When Francia began to focus on painting, the Bolognese artistic scene was active, though perhaps not as dominant as Florence or Venice. He did not emerge in a vacuum. His early painting style shows an affinity with the Ferrarese school, known for its sharp linearity, expressive intensity, and sometimes eccentric figural types. Artists like Ercole de' Roberti, who worked in Bologna for a period, are often cited as an early influence, particularly in terms of compositional structure and a certain crispness in delineation.

However, a more significant and lasting influence on Francia's developing style was Lorenzo Costa the Elder (c. 1460–1535). Costa, originally from Ferrara, settled in Bologna around 1483 and became a close associate, and possibly a partner, of Francia. The two artists collaborated on several projects, and their styles often show a remarkable similarity, sometimes making attributions difficult. Costa's art, while rooted in Ferrarese traditions, possessed a softer, more lyrical quality than that of his predecessors. It is generally believed that Costa's example helped Francia to temper the potential harshness of the Ferrarese style, guiding him towards a greater gentleness and sweetness in his figures. Their partnership was fruitful, and together they dominated the Bolognese painting scene for many years.

As Francia matured, his artistic horizons expanded. He became increasingly aware of developments in Umbrian and Florentine painting. The work of Pietro Perugino (c. 1446/1452–1523) was particularly impactful. Perugino, the leading master of the Umbrian school, was renowned for his serene, sweetly pious figures, his harmonious compositions, and his spacious, atmospheric landscapes. Francia adopted many of Perugino's stylistic traits: the gentle, oval faces of his Madonnas, the delicate rendering of drapery, the calm, devotional mood, and the use of soft, sfumato-like modeling. This "Peruginesque" quality became a hallmark of Francia's mature style, contributing to his immense popularity, especially for devotional paintings.

Later in his career, Francia also came under the spell of the younger Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, 1483–1520). Raphael, who himself had been a pupil of Perugino, was rapidly transforming the art of painting, ushering in the High Renaissance with his idealized figures, complex yet harmonious compositions, and profound understanding of human emotion. While Francia never fully embraced the dynamism and grandeur of Raphael's Roman works, he was clearly impressed by the younger master's grace and perfection. This admiration, as we shall see, is also tied to a famous, though perhaps apocryphal, anecdote concerning Francia's later years. Other artists whose work would have been known and potentially influential, even if indirectly, include Florentine masters like Fra Filippo Lippi and Andrea del Verrocchio, whose workshop produced Leonardo da Vinci, and the great Venetian painters like Giovanni Bellini, whose atmospheric light and color were transforming art in the Veneto.

Masterpieces and Stylistic Hallmarks

Francesco Francia's oeuvre consists primarily of religious subjects, with a particular focus on altarpieces and devotional images of the Madonna and Child. He also produced a number of fine portraits. His style is characterized by its technical refinement, gentle sentiment, and harmonious, if often conventional, compositions.

Religious Paintings:

Many of Francia's most celebrated works are altarpieces. The "Felicini Madonna" (c. 1494), painted for the Felicini Chapel in San Francesco, Bologna (now Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna), is an early masterpiece that demonstrates his growing command of composition and his characteristic sweetness. The Virgin is enthroned, flanked by saints, with a gentle, melancholic expression. The influence of Perugino is already palpable in the figural types and the overall mood.

His "Madonna and Child with Saints Augustine and Monica, Francis, Proculus, and Sebastian" (also known as the "Manzuoli Altarpiece," c. 1500, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna) is another significant work, showcasing his ability to organize multiple figures into a coherent and balanced sacra conversazione. The figures are rendered with a smooth, polished finish, and the colors are clear and harmonious.

The "Bentivoglio Altarpiece" (Madonna and Child with Saints Florian, Augustine, John the Evangelist and Sebastian, and kneeling donors Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza), painted around 1498-99 for the Bentivoglio Chapel in San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, is a testament to his status as the favored painter of Bologna's ruling family. The inclusion of donor portraits, rendered with Francia's characteristic precision, adds a personal dimension to the sacred scene.

Perhaps one of his most famous altarpieces is the "Assumption of the Virgin with Saints John the Baptist, Bernard, Benedict and George" (c. 1502-1505), originally for the church of San Frediano in Lucca (now in the Basilica di San Frediano). This work, with its upward-soaring Virgin and apostles gazing in wonder, displays a greater sense of movement and grandeur, though still imbued with Francia's typical gentleness.

Francia produced numerous smaller devotional paintings of the "Madonna and Child," which were highly sought after by private patrons. Examples can be found in major museums worldwide, such as the National Gallery, London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. These works often feature the Virgin with a tender, slightly melancholic expression, holding the Christ Child, set against a serene landscape. The landscapes themselves, often featuring distant blue hills and feathery trees, owe much to Perugino's example.

Portraits:

Francia was also an accomplished portraitist. His "Portrait of Federico Gonzaga" (c. 1510, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) depicts the young son of Isabella d'Este and Francesco II Gonzaga, future Duke of Mantua. The boy is presented with a sensitivity and psychological insight that demonstrates Francia's skill in capturing individual likeness and character. Another notable portrait is that of "Bishop Bernardo de' Rossi" (c. 1505, National Gallery, London), which, though sometimes attributed to other artists like Lorenzo Costa, shows the meticulous detail and refined execution typical of Francia. His experience as a medallist, requiring the ability to capture a likeness in a small scale, likely contributed to his success in portraiture.

Stylistic Characteristics Summarized:

Sweetness and Piety: Francia's figures, particularly his Madonnas and saints, exude a gentle, devotional sentiment. Their expressions are often serene, sometimes tinged with melancholy.

Refined Execution: Coming from a goldsmith's background, Francia brought a high level of craftsmanship to his paintings. Surfaces are smooth, details are meticulously rendered, and there is an overall sense of polish.

Harmonious Color: His palette is generally clear and bright, with harmonious color combinations that contribute to the peaceful mood of his works.

Balanced Compositions: Francia favored balanced, often symmetrical, compositions, particularly in his altarpieces. While not as dynamic as those of some High Renaissance masters, they are well-ordered and pleasing to the eye.

Peruginesque Influence: The impact of Perugino is evident in his figural types, landscape backgrounds, and the overall Umbrian sweetness that pervades much of his work.

Delicate Landscapes: His landscape backgrounds, often featuring rolling hills, feathery trees, and distant atmospheric perspective, provide a serene setting for his figures.

The Workshop, Pupils, and Collaborations

Like most successful Renaissance artists, Francesco Francia maintained an active workshop to help him fulfill commissions. He trained a number of pupils, ensuring the continuation of his style and influence in Bologna and beyond. His most famous pupil was undoubtedly Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1480–c. 1534). While Raimondi initially trained as a painter under Francia, he soon specialized in engraving. He became one of the most important printmakers of the Renaissance, renowned for his engravings after the works of Raphael, which played a crucial role in disseminating High Renaissance art throughout Europe. Francia's own background in engraving and metalwork likely provided a strong foundation for Raimondi's development in this medium.

Francia's sons, Giacomo Francia (c. 1484–1557) and Giulio Francia (1487–1540), also became painters and continued their father's workshop after his death. While competent artists, they largely worked in their father's style, sometimes collaborating with him on later commissions and completing unfinished works. Their adherence to Francia's established manner meant that the "Francia style" persisted in Bologna for some time, though it gradually became seen as somewhat old-fashioned with the rise of new artistic trends.

Other artists associated with his circle or influenced by him include Timoteo Viti, who, though primarily associated with Urbino and Raphael, is said to have spent some time in Francia's workshop. Amico Aspertini, a more eccentric Bolognese contemporary, also shows some stylistic connections, though his work is generally more dynamic and less serene than Francia's.

His collaboration with Lorenzo Costa was particularly significant in his early career. They are known to have worked together on decorations for the Bentivoglio palace and other projects. This partnership was crucial for Francia's artistic formation and helped establish both artists as the leading painters in Bologna at the turn of the 16th century.

The Shadow of Raphael and Later Years

A famous story, recounted by Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects," concerns Francia's encounter with Raphael's work late in his life. According to Vasari, Raphael painted his "Ecstasy of St. Cecilia" (c. 1514, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna) in Rome and sent it to Bologna to be installed in the church of San Giovanni in Monte. He supposedly entrusted Francia, as a respected elder artist, with overseeing its unpacking and installation.

Vasari claims that when Francia saw Raphael's masterpiece, he was so overwhelmed by its beauty, power, and perfection—so far exceeding his own achievements—that he fell into a deep melancholy and died shortly thereafter. This dramatic tale has been widely repeated and has contributed to an image of Francia as an artist acutely aware of his own limitations in the face of High Renaissance genius.

However, the historical accuracy of Vasari's account is questionable. While Francia would certainly have admired Raphael's "St. Cecilia," which is indeed a groundbreaking work, the notion that it directly caused his death is likely a romantic embellishment. Francia was already an elderly man by this time, and his death in 1517 could have been due to natural causes. Nevertheless, the story highlights the profound impact that Raphael and the High Renaissance had on the artistic consciousness of the period. It underscores a shift in artistic ideals, where the calm, devotional sweetness of artists like Francia and Perugino was being superseded by the dynamism, grandeur, and psychological depth of masters like Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo.

Despite this, Francia remained highly respected in Bologna until his death. He had achieved considerable fame and fortune through his art, and his works were sought after by patrons both within and outside the city. He was buried with honor in the church of San Francesco in Bologna.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Francesco Francia's reputation has fluctuated over the centuries. In his own time and for a period thereafter, he was considered the preeminent master of the Bolognese school. His gentle piety and refined execution appealed to the devotional sensibilities of his patrons. His influence on Bolognese painting was significant, primarily through his sons and pupils who continued his style.

However, with the rise of the Carracci (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico) in Bologna at the end of the 16th century, who initiated a new, more dynamic and naturalistic phase of Bolognese art, Francia's style began to be seen as somewhat dated. The Carracci themselves looked more towards Raphael, Correggio, and Venetian masters like Titian and Veronese for inspiration.

During the 19th century, there was a revival of interest in Early Renaissance and "primitive" painters, and Francia's work, with its sincere piety and delicate charm, found renewed appreciation, particularly among collectors and connoisseurs in England and Germany. His paintings were praised for their quiet beauty and spiritual depth, qualities that resonated with Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite sensibilities.

Modern art historical assessment places Francia as a significant transitional figure. He successfully bridged the gap between the late Quattrocento style, with its roots in local traditions and Ferrarese influences, and the emerging ideals of the High Renaissance. While he may not have possessed the innovative genius of a Leonardo, a Raphael, or a Michelangelo, he was a highly skilled and sensitive artist who absorbed and synthesized various influences to create a distinctive and appealing style. His work embodies the artistic aspirations of Bologna at a crucial moment in its history, reflecting the city's cultural sophistication and its engagement with broader Italian Renaissance trends.

His paintings are admired for their technical accomplishment, their gentle emotional appeal, and their harmonious beauty. He excelled in creating images that were both aesthetically pleasing and conducive to religious devotion. His legacy is that of a master craftsman who successfully translated his skills into the realm of painting, becoming the leading figure of his local school and leaving behind a body of work that continues to charm and inspire. He stands as a testament to the rich diversity of artistic expression within the Italian Renaissance, where regional centers like Bologna made their own unique contributions to the era's extraordinary cultural flowering, alongside the more celebrated achievements of Florence, Rome, and Venice. His art, while perhaps overshadowed by the giants of the High Renaissance like Titian or Giorgione, remains a vital part of Italy's artistic heritage.