Piero della Francesca stands as one of the most distinctive and intellectually profound artists of the Italian Early Renaissance. Active primarily in the mid-15th century, he was a figure whose life and work uniquely bridged the burgeoning fields of mathematical theory and artistic practice. Born Piero di Benedetto de' Franceschi around 1415-1420 in the small Tuscan town of Borgo San Sepolcro (modern-day Sansepolcro), he remained deeply connected to his hometown throughout his life, eventually passing away there on October 12, 1492 – the very day Christopher Columbus is traditionally credited with reaching the Americas. His legacy is one of serene, monumental paintings characterized by geometric precision, masterful handling of light and perspective, and an air of solemn, almost otherworldly calm.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who flocked permanently to major artistic centers, Piero maintained a strong base in Sansepolcro while undertaking significant commissions in cities like Florence, Rimini, Arezzo, Ferrara, Rome, and notably, Urbino. This geographical range exposed him to various artistic currents and patrons, yet his style retained a remarkable consistency and individuality. He was not merely a painter; he was a dedicated mathematician and theorist, authoring treatises on perspective, geometry, and mathematics that were groundbreaking in their time and reveal the intellectual rigor underpinning his artistic vision. His work embodies the Renaissance ideal of the artist as thinker, scientist, and craftsman.

Early Life and Florentine Foundations

Details of Piero's earliest training remain somewhat obscure, though it likely began in his native Sansepolcro. A pivotal moment came in the late 1430s when documents place him in Florence, working as an assistant to Domenico Veneziano on frescoes (now lost) for the choir of Sant'Egidio. Florence during this period was the crucible of the Renaissance, buzzing with artistic and intellectual innovation. Here, Piero would have directly encountered the revolutionary developments transforming painting, sculpture, and architecture.

The influence of Florence's leading artistic lights on Piero is undeniable, though filtered through his unique sensibility. He absorbed the lessons of Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect who had codified linear perspective, providing artists with a mathematical system to create convincing illusions of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Piero would become one of perspective's most sophisticated practitioners.

He also witnessed the powerful realism and volumetric solidity of figures painted by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel, whose work marked a definitive break from the decorative elegance of the International Gothic style. Masaccio's use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model form and create dramatic intensity left a lasting impression, although Piero would adapt this towards a cooler, more even luminosity. The sculptural gravity found in the works of Donatello also likely informed Piero's own monumental and dignified figures. His time with Domenico Veneziano, himself a master of subtle light and color, was crucial in refining Piero's own approach to atmospheric effects and palette.

The Mathematical Artist: Perspective and Geometry

Piero della Francesca's profound engagement with mathematics is central to understanding his art. He was not simply applying rules learned from others; he was actively investigating and contributing to mathematical knowledge. His intellectual pursuits culminated in three major treatises: the Trattato d'abaco (Abacus Treatise), a practical guide to arithmetic and algebra relevant to merchants and scholars; De prospectiva pingendi (On Perspective for Painting); and Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus (Short Book on the Five Regular Solids).

De prospectiva pingendi, likely written in the 1470s, is arguably his most significant theoretical work for art history. It was one of the earliest and most comprehensive manuals detailing the principles of linear perspective. Going beyond the foundational work of Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti, Piero provided rigorous geometric proofs and detailed instructions on how to represent objects, figures, and architectural spaces accurately in foreshortening. His approach was methodical and scientific, demonstrating how mathematical principles could create visually coherent and harmonious compositions.

This mathematical underpinning is evident everywhere in his paintings. Compositions are often built upon clear geometric structures – squares, circles, triangles – creating a sense of underlying order and stability. Figures possess a volumetric solidity derived from their geometric conception. Architectural settings are rendered with meticulous perspectival accuracy, creating believable, rational spaces that the figures inhabit with quiet authority. This fusion of art and mathematics reflected the humanist belief in a rationally ordered universe, discoverable through both empirical observation and intellectual inquiry. Piero saw geometry as the fundamental structure underlying the visible world, and perspective as the key to representing it truthfully.

Masterworks of Serene Monumentality

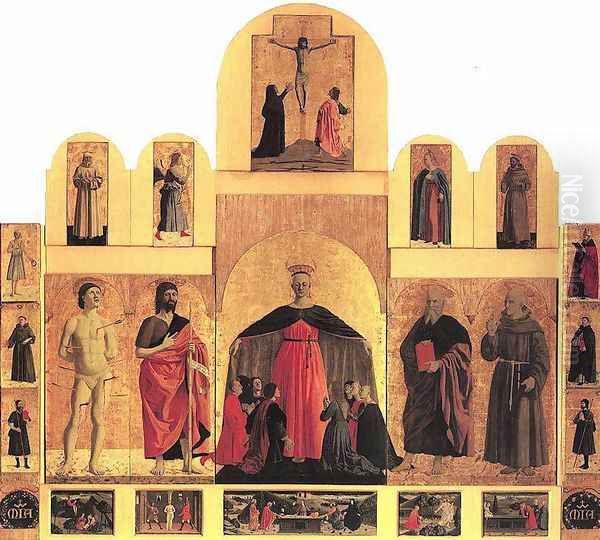

Piero's surviving oeuvre, though not vast, includes several masterpieces that exemplify his unique style. Each work showcases his command of form, light, and composition, imbued with a characteristic stillness and intellectual depth.

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1450s), now in the National Gallery, London, is a work of remarkable clarity and balance. Christ stands centrally in the Jordan River, flanked by John the Baptist and three angels, under the dove of the Holy Spirit. The composition is rigorously symmetrical, anchored by the vertical axis running through Christ and the dove, and the tree on the left which perfectly balances the figures on the right. The light is cool and even, bathing the scene in an almost shadowless clarity that defines forms with precision. The landscape recedes gently, rendered with careful attention to atmospheric perspective. The figures possess a calm dignity, their gestures restrained, contributing to the overall atmosphere of profound spiritual significance and tranquility. The influence of Domenico Veneziano's handling of light is particularly apparent here.

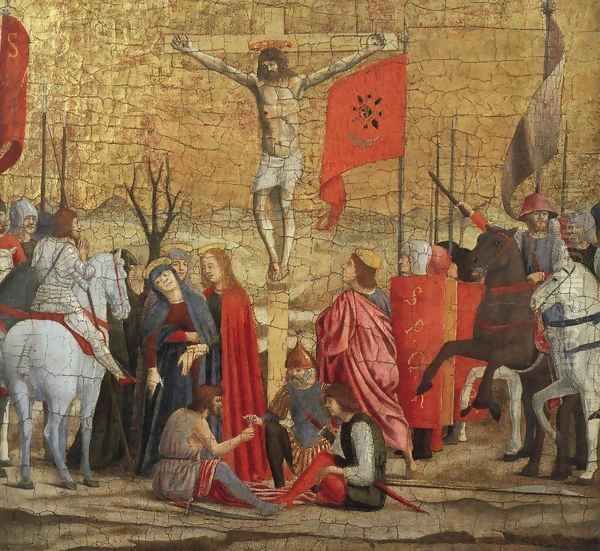

Perhaps Piero's most extensive and celebrated work is the fresco cycle The Legend of the True Cross (c. 1452-1466) in the Cappella Maggiore of the Basilica di San Francesco in Arezzo. Commissioned by the wealthy Bacci family, these frescoes cover three walls of the chapel, depicting episodes from the story of the wood of Christ's cross, based on Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend. Despite the narrative complexity and dramatic potential of scenes like the Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes, Piero maintains a sense of measured solemnity. Figures are monumental and statuesque, arranged in carefully balanced groups. Compositions like The Dream of Constantine, with its innovative nocturnal lighting, demonstrate his mastery of light and perspective to create mood and space. The entire cycle is a testament to his ability to organize complex narratives within a visually coherent and harmonious framework.

The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1460), housed in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, is one of Piero's most enigmatic works. The small panel is divided into two distinct spatial zones by a column. On the left, within a meticulously rendered classical portico, the biblical scene of Christ's flagellation takes place in the background. On the right, occupying the foreground, stand three unidentified figures in contemporary dress, engaged in quiet conversation. The painting's precise geometric construction, cool light, and the emotional detachment of the figures have generated numerous interpretations regarding its meaning and the identity of the foreground figures. It is a prime example of Piero's intellectual approach, inviting contemplation rather than immediate emotional response. Its likely patron was Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, a renowned humanist and condottiero.

Another iconic work is The Resurrection (c. 1460s), a fresco painted for the town hall (Palazzo dei Conservatori) of his native Sansepolcro. Christ emerges triumphantly from the tomb, holding the banner of the Resurrection, his figure forming the apex of a stable pyramid composition. Below him, four Roman soldiers sleep, their forms rendered with sculptural solidity. The composition is starkly symmetrical and hieratic, emphasizing the divine power and solemnity of the event. Christ's gaze is direct and commanding, yet impassive. The landscape transitions from barren on one side to leafy on the other, symbolizing death and rebirth. This work held great civic importance for Sansepolcro, embodying the town's identity (whose name means "Holy Sepulchre").

Piero was also a gifted portraitist. The famous diptych Portraits of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza (c. 1472-74), now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, depicts the Duke and Duchess of Urbino in strict profile, a format recalling classical coins and medals but also common in Italian court portraiture. Against detailed panoramic landscapes representing their territories, the sitters are rendered with unflinching objectivity. Federico's distinctive broken nose and Battista's high forehead and pallor are recorded precisely. Despite the profile view, Piero conveys a sense of their presence and status. The reverse panels feature allegorical triumphs, further celebrating the ducal couple. This work contrasts with the burgeoning three-quarter view popularised by Flemish artists like Jan van Eyck, showing Piero adhering to Italian traditions while investing them with his characteristic clarity and detail.

The Brera Madonna, also known as the Montefeltro Altarpiece (c. 1472-74), shows Federico da Montefeltro kneeling in prayer before the Virgin and Child, surrounded by saints within a magnificent classical apse. The architectural setting is rendered with breathtaking perspectival accuracy. The figures, including the Duke in gleaming armor, possess Piero's typical stillness and gravitas. Details like the ostrich egg hanging from the scallop shell niche are rendered with meticulous care and likely hold complex symbolism. The work exemplifies the sacra conversazione (holy conversation) format, presenting a scene of quiet devotion and intellectual order, perfectly suited to the humanist court of Urbino.

Light, Color, and Atmosphere

Beyond perspective and geometry, Piero's handling of light and color is fundamental to his style. He favored a cool, clear, and pervasive light that seems to emanate from within the scene itself rather than from a single identifiable source. This light defines forms with crisp edges and subtle modeling, often minimizing cast shadows to create an effect of even illumination and heightened clarity. It contributes significantly to the serene, timeless quality of his work, lifting the scenes beyond the everyday into a realm of idealized order.

His color palette is distinctive, often employing luminous blues, reds, whites, and earth tones. Colors are applied in broad, smooth areas, contributing to the sense of solidity and structure in his compositions. He understood the relationship between light and color, using subtle tonal variations to suggest depth and atmosphere, particularly in his landscapes which often feature pale, receding horizons under vast skies. This careful calibration of light and color enhances the overall harmony and balance of his paintings.

The prevailing atmosphere in Piero's work is one of profound stillness and intellectual detachment. His figures rarely display overt emotion; instead, they possess a solemn dignity and introspective calm. Gestures are measured and deliberate. Even in potentially dramatic scenes, like battles or martyrdoms, there is a sense of suspended time and monumental gravity. This emotional restraint invites viewers to contemplate the scene's underlying structure and meaning rather than being swept away by narrative drama. This contrasts sharply with the more dynamic or emotionally charged styles of contemporaries like Andrea del Castagno or the lyrical sweetness found in the works of Fra Filippo Lippi.

Influence and Connections

Piero della Francesca's artistic journey involved interactions with various centers and artists, creating a web of influences both received and given. His formative Florentine experience connected him to the legacy of Brunelleschi, Masaccio, and Donatello, and his collaboration with Domenico Veneziano was crucial. While stylistically different from the Dominican friar-painter Fra Angelico, known for his radiant color and devout spirituality, Piero shared with him a mastery of clear light and compositional order, albeit applied with a more rigorously mathematical and detached sensibility.

Working for patrons like Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta in Rimini and Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino placed him within sophisticated court environments. In Urbino, he would have encountered figures associated with Federico's culturally rich court, possibly including the architect Luciano Laurana, who was involved in the Ducal Palace's design, reflecting a shared interest in classical proportion and perspective.

Piero's influence on subsequent generations is significant, though sometimes subtle. Artists working in central Italy, such as Melozzo da Forlì, known for his mastery of foreshortening (perhaps learned from Piero), and Luca Signorelli, traditionally considered Piero's pupil, show clear debts to his monumental figures and spatial clarity. Signorelli's powerful frescoes at Orvieto Cathedral, while more dynamic and emotionally intense, build upon the volumetric solidity pioneered by Piero.

The Umbrian painter Perugino, master of Raphael, also developed a style characterized by spacious compositions, clear light, and calm figures, which resonates with Piero's aesthetic, suggesting an indirect influence. Through Perugino and perhaps direct exposure to Piero's works, the young Raphael likely absorbed lessons in compositional harmony and idealized form. Even Leonardo da Vinci, whose scientific curiosity paralleled Piero's own mathematical interests, can be seen as inheriting the tradition of integrating empirical observation and theoretical knowledge into art, a path Piero had significantly advanced.

Later Years and Theoretical Work

Towards the end of his life, particularly from the 1480s onwards, Piero seems to have dedicated himself increasingly to his mathematical and theoretical studies, apparently painting less. The 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari reported that Piero became blind in his old age, which, if true, would explain a cessation of painting activity. However, the exact timing and extent of this blindness are debated by modern scholars. His will, dated 1487, describes him as "sound in mind, intellect, and body," suggesting he was still capable at that time.

Regardless of the reason, his later years were certainly marked by intense intellectual activity focused on completing his treatises. These writings, particularly De prospectiva pingendi and Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus, represent a major contribution to Renaissance theoretical literature. They circulated in manuscript form and influenced artists and mathematicians. Notably, Luca Pacioli, a fellow native of Sansepolcro and a renowned mathematician himself, drew heavily upon Piero's work (sometimes without full attribution) for his own influential book De divina proportione (On the Divine Proportion), published in 1509 with illustrations based on designs by Leonardo da Vinci. This demonstrates the continued relevance of Piero's mathematical investigations well into the High Renaissance.

Rediscovery and Modern Legacy

Despite his importance, Piero della Francesca's fame somewhat faded after the 16th century. While Vasari included him in his Lives of the Artists, praising his scientific knowledge and skill, subsequent generations perhaps found his austere, unemotional style less appealing than the dynamism of the High Renaissance or the drama of the Baroque. His works remained largely in provincial centers like Arezzo and Sansepolcro, outside the main routes of artistic pilgrimage.

A significant revival of interest began in the mid-19th century, accelerating in the early 20th century. Art historians and critics, particularly in Britain and France, rediscovered his work and recognized its unique qualities. The influential critic Bernard Berenson lauded his "impersonality" and "unemotional" grandeur. Roger Fry, a key figure in the Bloomsbury Group, championed Piero as one of the greatest Italian painters, praising his formal purity, geometric structure, and intellectual depth. Fry saw in Piero's work qualities that resonated with modern artistic sensibilities, particularly the move towards abstraction and formal concerns seen in Post-Impressionism and Cubism.

Indeed, Piero's emphasis on form, structure, and serene order struck a chord with many modern artists. His influence can be detected in the pointillist compositions of Georges Seurat, the enigmatic, architectural spaces of Giorgio de Chirico's Metaphysical Painting, and the monumental, silent figures of Balthus. British artists like Stanley Spencer and Winifred Knights were also deeply impressed by his frescoes during visits to Italy, absorbing lessons in composition and figure modeling. Piero's art, once seen as perhaps too cold or remote, came to be appreciated for its timeless monumentality, its intellectual rigor, and its profound, quiet beauty.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Piero della Francesca occupies a unique and pivotal position in the history of Western art. He was a quintessential Renaissance man, seamlessly blending the practical craft of painting with the theoretical rigor of mathematics. His works are characterized by an unparalleled synthesis of observation and abstraction, realism and idealization. His mastery of linear perspective allowed him to create rational, harmonious spaces, while his handling of light and color imbued his scenes with a luminous clarity and serene atmosphere.

His figures possess a solemn, statuesque dignity, embodying humanist ideals of order, reason, and intellectual contemplation. While perhaps less immediately accessible than the works of some of his more emotionally expressive contemporaries, Piero's paintings offer enduring rewards through their formal perfection, intellectual depth, and profound sense of peace. From the groundbreaking frescoes in Arezzo to the enigmatic panel in Urbino and the iconic portraits, his art continues to fascinate and inspire. Rediscovered and celebrated in the modern era, Piero della Francesca remains a testament to the power of a singular artistic vision grounded in the harmonious interplay of art and science.