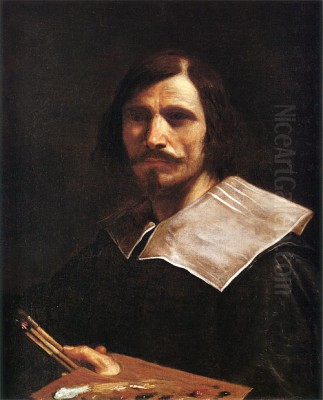

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known to the world as Guercino, stands as one of the most compelling and influential figures of the Italian Baroque period. Born in the small town of Cento, nestled in the Emilia region near Ferrara and Bologna, in 1591, his life spanned a period of immense artistic ferment and transformation. His unique nickname, Guercino, meaning "little squinter," stemmed from a permanent strabismus he developed as an infant, reportedly after a sudden fright. This physical characteristic, however, never hindered his artistic vision; indeed, some have speculated it contributed to the unique intensity and observational power evident in his work. Active primarily in Cento, Rome, and Bologna, Guercino left behind a vast and varied body of work, encompassing dramatic altarpieces, evocative mythological scenes, sensitive portraits, and an extraordinary number of highly prized drawings. His career charts a fascinating course from the robust naturalism and dramatic lighting of the early Baroque towards a more classical, balanced, and luminous style in his later years.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Emilia

Guercino's artistic journey began not in the structured environment of a major academy, but largely through self-instruction, fueled by an innate talent and keen observation. Growing up in Cento, he absorbed the artistic currents of the nearby centres of Ferrara and Bologna. Early influences included Ferrarese painters like Ippolito Scarsellino and Carlo Bononi, whose works displayed rich colour and emotional depth. However, the most significant early impact came from Bologna, particularly from the work of Ludovico Carracci.

Ludovico, along with his cousins Annibale Carracci and Agostino Carracci, had spearheaded a reform of painting in Bologna, moving away from the artificiality of late Mannerism towards a renewed emphasis on drawing from life, naturalism, and clear emotional expression. Though Guercino was never formally a student at the Carracci Academy (Accademia degli Incamminati), he deeply assimilated Ludovico's dynamic compositions, warm palette, and affecting portrayal of human sentiment. His early works are characterized by this robust naturalism, combined with a powerful use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – reminiscent of the revolutionary Lombard painter Caravaggio, whose influence was spreading rapidly throughout Italy.

Around the age of sixteen, Guercino briefly associated with the workshop of Benedetto Gennari the Elder in Cento, but his distinctive style developed rapidly and independently. By 1617, his reputation had grown sufficiently that he was running his own busy studio and even co-founded an "Accademia del Nudo" (Academy of the Nude) in Cento, emphasizing life drawing – a core tenet derived from the Carracci reforms. A pivotal trip to Venice in 1618 further enriched his style. There, he encountered the masterpieces of Venetian Renaissance painters like Titian and Tintoretto, absorbing their mastery of colour, light, and atmospheric effects, which added a new layer of richness to his Emilian foundations.

Early Masterworks and Rising Fame

The period before his move to Rome saw Guercino produce works of startling originality and power, establishing his reputation beyond his native region. Paintings like the Madonna and Child with a Sparrow (c. 1615-16, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale) showcase his early tenderness and naturalistic approach, combined with a soft, atmospheric light. Other works demonstrate a more forceful drama.

His Et in Arcadia Ego (c. 1618-1622, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica), depicting shepherds contemplating a skull inscribed with the titular phrase ("Even in Arcadia, I [Death] am present"), is a poignant meditation on mortality, rendered with vigorous brushwork and earthy realism. The Return of the Prodigal Son (c. 1619, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) exemplifies his early mastery of dramatic narrative and emotional intensity, using strong contrasts of light and shadow to focus the viewer's attention on the core interaction.

His handling of mythological and religious subjects was equally compelling. Works like Susanna and the Elders (1617, Madrid, Prado Museum) combine sensuousness with dramatic tension, while altarpieces such as Saint William of Aquitaine Receiving the Cowl (1620, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), originally painted for the church of San Gregorio in Bologna, demonstrate his ability to handle large-scale compositions with dynamic energy and profound piety. These early successes, marked by their vigorous naturalism, bold chiaroscuro, and often turbulent emotion, caught the attention of influential patrons.

The Call to Rome and Papal Patronage

A turning point in Guercino's career came in 1621. Alessandro Ludovisi, a Bolognese cardinal who deeply admired Guercino's work, was elected Pope Gregory XV. Recognizing the painter's exceptional talent, the new Pope summoned Guercino to Rome. This move placed Guercino at the very centre of the Italian art world, exposing him to a wider range of artistic influences and offering him prestigious commissions.

Rome in the 1620s was a crucible of artistic activity. While Caravaggio's dramatic realism still resonated, the classical idealism championed by Annibale Carracci and his followers, such as Domenichino and Guido Reni (though Reni was primarily based in Bologna), was gaining prominence. The patronage of powerful families like the Ludovisi (the Pope's family) and the Borghese fueled a demand for grand decorative schemes and altarpieces.

Guercino quickly secured major commissions, working alongside other leading artists of the day. His arrival coincided with a period where artists like Giovanni Lanfranco were also exploring dynamic Baroque ceiling decorations. Guercino's Emilian training, combined with his innate talent, allowed him to compete effectively in this demanding environment.

Roman Masterpieces: Fresco and Canvas

During his relatively brief stay in Rome (1621-1623), Guercino produced some of his most celebrated works, demonstrating his versatility in both fresco and oil painting. His most famous Roman commission was the ceiling fresco of Aurora (1621-1623) for the Casino Ludovisi, a garden house belonging to the Pope's nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi. Unlike the more contained, framed approach (quadro riportato) often seen in earlier ceiling paintings, Guercino created a dynamic, illusionistic scene where Aurora, the goddess of dawn, scatters flowers from her chariot across a luminous sky. The work is a triumph of Baroque illusionism and atmospheric light, rivaling Guido Reni's earlier, more classically restrained Aurora fresco in the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi.

Equally significant was the monumental altarpiece, The Burial and Reception into Heaven of Saint Petronilla (1623), commissioned for St. Peter's Basilica (now in the Capitoline Museums, Rome). This vast canvas depicts two registers: the burial of the saint below, rendered with poignant realism and dramatic lighting reminiscent of his earlier style, and her glorious reception into heaven above, painted with a brighter palette and more idealized forms. This work, considered one of the cornerstones of High Baroque painting, shows Guercino beginning to temper his earlier tenebrism with a greater clarity and classical structure, perhaps influenced by the prevailing Roman taste and the works of artists like Domenichino.

Other works from this period, such as the Persian Sibyl (1622, Capitoline Museums), continue to show his mastery of expressive figures and rich colour. The Roman experience was transformative, exposing Guercino to classical antiquity and the work of High Renaissance masters like Raphael, subtly shifting his artistic trajectory.

Return to Emilia: Maturity and the Bolognese Studio

Pope Gregory XV's death in 1623 abruptly ended the Ludovisi patronage and prompted Guercino's return to his hometown of Cento. Despite opportunities to remain in Rome or accept prestigious invitations from monarchs like Charles I of England and Louis XIII of France, Guercino preferred the familiar environment of Emilia. He remained in Cento for nearly two decades, running a highly successful studio and fulfilling numerous commissions from across Italy and Europe.

His style continued to evolve during this period. While retaining emotional depth, his compositions became more balanced, his lighting less starkly contrasted, and his figures often imbued with a greater sense of grace and classical poise. This gradual shift towards a more classical Baroque idiom became more pronounced over time.

In 1642, following the death of Guido Reni, the dominant figure in Bolognese painting, Guercino made a significant move. He relocated his thriving workshop from Cento to Bologna, effectively stepping into the preeminent position previously held by Reni. Bologna, with its strong artistic traditions and wealthy clientele, provided a fertile ground for the final phase of his career. His studio became a major centre of production and training.

The Later Style: Classicism and Clarity

Guercino's later works, particularly those produced after his move to Bologna, are characterized by a distinct shift towards a more classical aesthetic. The dramatic intensity and turbulent energy of his youth gave way to compositions marked by greater clarity, balance, and emotional restraint. His palette lightened considerably, favouring cooler tones and more subtle gradations of light and shadow, replacing the stark chiaroscuro of his early years with a softer, more diffused luminosity.

Figures became more idealized, their gestures often more measured and graceful, reflecting the influence of Bolognese classicism as exemplified by Reni and Domenichino. Works like Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph (1650s - versions exist, e.g., National Gallery of Ireland), The Annunciation (1629, Forlì Pinacoteca Civica - an earlier example showing the transition), and the later Assumption of the Virgin (versions exist, e.g., 1650, Hermitage Museum) exemplify this mature style. They possess a calm dignity and a refined emotional tenor, often emphasizing piety and narrative clarity in line with Counter-Reformation ideals.

Some critics have debated the reasons for this stylistic evolution, suggesting it might have been a conscious decision to align with prevailing tastes or a natural artistic development towards greater refinement. Regardless of the motivation, these later works demonstrate Guercino's enduring ability to adapt and innovate throughout his long career, mastering a different, yet equally compelling, mode of Baroque expression. His output remained prolific, including numerous altarpieces, devotional paintings, and mythological scenes.

Guercino the Master Draughtsman

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Guercino was one of the most gifted and prolific draughtsmen of the Baroque era. Thousands of his drawings survive, housed in major collections worldwide, most notably the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These drawings were not merely preparatory studies for paintings but often works of art in their own right, prized by collectors even during his lifetime.

His drawing style is characterized by its fluidity, energy, and expressive use of line and wash. He frequently employed pen and brown ink, often combined with brown wash applied with a brush, to create dynamic effects of light and shadow that mirrored the chiaroscuro of his paintings. His subjects ranged from rapid compositional sketches and figure studies from life (reflecting his academy's focus) to detailed landscape drawings and even caricatures.

The sheer volume and consistent quality of his graphic output are remarkable. His drawings reveal his working process, his keen observation of the human form and nature, and his ability to capture movement and emotion with astonishing economy and vitality. His technical brilliance and expressive power as a draughtsman have led some scholars to compare him to Peter Paul Rubens, another Baroque giant renowned for his graphic work, sometimes referring to Guercino as the "Rubens of the South" in this regard.

Workshop, Students, and Legacy

Guercino ran a large and highly organized workshop, particularly after his move to Bologna. This studio was essential for managing the high demand for his work and for executing large-scale commissions. He relied on assistants for various tasks, from preparing canvases to painting less critical areas of compositions, although the master's hand is usually evident in the key figures and overall design.

He was also an influential teacher. His Accademia del Nudo in Cento and his later Bolognese studio attracted numerous pupils. Among the most notable were his own nephews, Benedetto Gennari II and Cesare Gennari, who inherited the workshop and continued working in a style heavily indebted to their uncle. Other documented pupils include Giulio Coralli, Giuseppe Bonati, Cristoforo Serra, Sebastiano Ghezzi, Sebastiano Bombelli, Lorenzo Bergonzoni, Francesco Paglia, Bartolomeo Caravoglia (distinct from the more famous Caravaggio), Benedetto Zalone, and Matteo Loves.

Guercino's influence extended beyond his direct pupils. His powerful early style impacted artists across Italy, while his later classicism resonated with the evolving tastes of the mid-17th century. His works were collected internationally, influencing artists in Spain, France, and England. His ability to convey deep emotion through dramatic composition and light, combined with his later classical grace, ensured his enduring importance in the narrative of Baroque art. He died a wealthy and highly respected artist in Bologna in 1666.

Artistic Relationships and Anecdotes

Throughout his career, Guercino navigated relationships with patrons, fellow artists, and critics. His primary influence, Ludovico Carracci, represented the Bolognese tradition he initially embraced. While influenced by Caravaggio's innovations in light, there's no record of direct contact. His relationship with Guido Reni was complex; initially distinct stylistically, Guercino's later work moved closer to Reni's classicism, and he ultimately succeeded Reni as Bologna's leading painter. He worked alongside artists like Domenichino and Lanfranco in Rome.

He maintained a close friendship with Fra Bonaventura Bisi, a painter and miniaturist, whose portrait Guercino painted with sensitivity. His patrons included the highest ecclesiastical figures, like Pope Gregory XV and Cardinal Ludovisi, as well as Italian nobility and international collectors. Anecdotes, like the story of Queen Christina of Sweden supposedly asking him to demonstrate painting with his left hand (likely apocryphal or exaggerated), speak to his fame and perceived virtuosity.

His personal life remains somewhat enigmatic. He never married, dedicating himself entirely to his art. The nickname "Guercino," stemming from his strabismus, became his accepted professional identity. Despite this visual impairment, his observational skills were extraordinary, perhaps even heightened, allowing him to capture subtle nuances of expression and anatomy. He was known for his diligence and the remarkable speed at which he could work, contributing to his immense output.

Critical Reception and Enduring Significance

Guercino enjoyed immense fame and financial success during his lifetime. His works were highly sought after, and he was regarded as one of Italy's leading painters. However, critical fortunes can fluctuate. While his early, more dramatic works align well with modern appreciation for Baroque energy, his later, more classical style was sometimes viewed less favourably by critics in the 18th and 19th centuries, who occasionally saw it as a decline from his initial power or an overly pious concession to Counter-Reformation tastes.

Controversies occasionally arose. The sensuous treatment of figures, particularly the male nude, in some works drew criticism from conservative elements within the Church, although this was not uncommon for Baroque artists exploring the human form. Modern scholarship sometimes discusses potential homoerotic undertones in certain depictions, interpreting them within the complex cultural context of the period. Attribution issues have also occurred, with some of his works occasionally misattributed to Reni or others, though modern connoisseurship and technical analysis have clarified many of these cases.

Today, Guercino is fully recognized as a giant of the Italian Baroque. His stylistic journey from dynamic naturalism to refined classicism is seen not as a decline but as a testament to his versatility and responsiveness to the artistic currents of his time. His mastery of light and shadow, his profound psychological insight, his narrative power, and his exceptional skill as a draughtsman secure his place in the pantheon of great artists. His paintings and drawings continue to captivate viewers with their emotional resonance and technical brilliance, offering a rich and complex vision of the Baroque age.