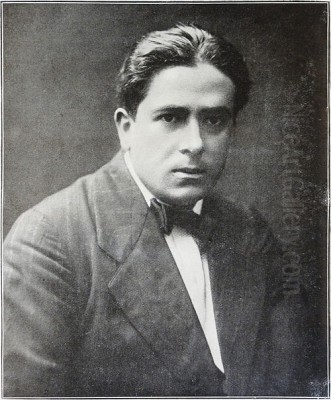

Francis Picabia stands as one of the most enigmatic, versatile, and provocative figures of twentieth-century art. A key player in the revolutionary movements of Dadaism and Surrealism, his career was marked by constant stylistic reinvention, a rebellious spirit, and a profound engagement with the changing world around him. Born in Paris on January 22, 1879, to a Spanish-Cuban father and a French mother, Picabia navigated the tumultuous currents of modernism, leaving behind a body of work that continues to challenge, amuse, and inspire. His multifaceted career encompassed not only painting but also poetry, writing, typography, and even filmmaking, cementing his legacy as a true avant-garde polymath. He passed away in his native Paris on November 30, 1953.

Early Explorations: From Impressionism to Abstraction

Picabia's artistic journey began under the sway of Impressionism. Coming from a wealthy background, he received formal training at the École des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. In his early years, he absorbed the lessons of Impressionist masters, particularly Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro. His landscapes and cityscapes from this period, executed with a delicate touch and sensitivity to light, quickly gained recognition and commercial success. He exhibited regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français and the Salon d'Automne.

However, this early success was not without its whispers of controversy. Some critics noted a resemblance between his compositions and popular postcards or photographs of the era, raising questions about originality – a theme that would ironically resurface in different forms throughout his career. Despite this, these early works demonstrated a clear technical skill and an eye for capturing atmospheric effects, laying the groundwork for his later, more radical departures.

By 1908-1909, Picabia began to shed the skin of Impressionism, seeking a more modern and personal form of expression. This transition led him towards Fauvism and, more significantly, Cubism. He became associated with the Puteaux Group (also known as the Section d'Or), a collective of artists exploring Cubist principles, which included figures like Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, and the Duchamp brothers – Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and Jacques Villon. His friendship with Marcel Duchamp, in particular, would become a defining relationship in his life and career.

During this period, Picabia experimented intensely with form and color. His 1909 painting, Caoutchouc (Rubber), is often cited as a landmark work, potentially one of the very first purely abstract paintings in Western art. This piece marked a decisive break from representational imagery, prioritizing instead the dynamic interplay of shapes and colors. It signaled Picabia's growing commitment to abstraction and his willingness to push the boundaries of painting, moving alongside pioneers like Wassily Kandinsky, though arriving at abstraction through a different path rooted in Cubist analysis.

The Mechanomorphic Impulse and the Rise of Dada

A pivotal moment came with Picabia's trips to the United States, particularly his visit in 1913 for the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York. This exhibition introduced European modernism to an American audience on an unprecedented scale. Picabia, alongside Marcel Duchamp, became a sensation. In New York, he connected with influential figures like the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz and the artist Man Ray. The energy, technology, and perceived materialism of American culture profoundly impacted him.

This experience fueled the development of what is often called his "mechanomorphic" style. Fascinated by machines, technology, and their relationship to human desire and function, Picabia began creating works that used mechanical diagrams and machine parts as metaphors for human psychology and relationships. Paintings like Udnie (Young American Girl; The Dance) (1913) and Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic) (1913) combined abstract forms derived from Cubism with a sense of mechanical movement and energy.

These works, along with his collaborations with Duchamp and Man Ray, laid the groundwork for New York Dada. Dada, which officially emerged in Zurich around 1916 as a response to the absurdity and carnage of World War I, was an anti-art movement that embraced irrationality, chance, irony, and protest against bourgeois values and traditional aesthetics. Picabia, with his iconoclastic attitude and machine-inspired art, was a natural fit.

Returning to Europe, Picabia became a central figure in the Dada movement as it spread. He spent time in Barcelona, where he founded the avant-garde magazine 391 in 1917. This publication, which he continued intermittently until 1924, became a vital platform for Dadaist ideas, featuring contributions from artists and writers across Europe and America, including Tristan Tzara, Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, and Jean Arp. 391 was known for its provocative content, experimental typography, and Picabia's own biting wit and polemical writings.

In Zurich and later Paris, Picabia fully immersed himself in Dada activities. He participated in chaotic performances, wrote manifestos, and continued to produce challenging artworks. His "mechanomorphic" portraits, such as the ink drawing Portrait of Tristan Tzara (1920) or Portrait of Cézanne (1920), depicted individuals as absurd, non-functional machines, mocking traditional portraiture and the cult of the artist. L'Œil cacodylate (The Cacodylic Eye) from 1921, a canvas covered in autographs and graffiti by his avant-garde friends (including Tzara, Éluard, Soupault, and even potentially figures passing through like Ernest Hemingway), became a collective Dadaist statement, rejecting the notion of singular authorship.

Dada's Demise and the Surrealist Interlude

Picabia's commitment to Dada, however, was as volatile as the movement itself. By 1921, he dramatically broke with the Paris Dadaists, particularly Tristan Tzara and André Breton, who were increasingly vying for leadership. Picabia publicly denounced the movement in 391, declaring that Dada was no longer novel and had become institutionalized – a fate anathema to its core principles. He famously wrote, "The Dada spirit only existed from 1913 to 1918... In 1921, Dada is no longer anything."

Despite this break, Picabia briefly aligned himself with the nascent Surrealist movement, led by his former Dada colleague André Breton. Surrealism sought to unlock the power of the unconscious mind, drawing inspiration from dreams, psychoanalysis (particularly the work of Sigmund Freud), and automatic techniques. Picabia contributed to early Surrealist publications and exhibitions.

His most significant contribution during this phase was the Transparencies series, produced mainly between the late 1920s and early 1930s. These paintings featured overlapping layers of figurative outlines drawn from diverse sources – Renaissance art, Catalan frescoes, popular illustration. The effect is ethereal and dreamlike, creating complex, ambiguous narratives where figures and forms interpenetrate. Works like Hera (c. 1929) and Sphinx (c. 1929) exemplify this style, which resonated with Surrealist interests in layered meanings and the juxtaposition of disparate realities, echoing perhaps the layered imagery found in the works of Max Ernst or the dreamscapes of Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico.

However, Picabia's independent spirit soon led him away from organized Surrealism as well. He found Breton's attempts to codify the movement and exert control restrictive. By the mid-1920s, he had largely distanced himself, preferring to follow his own unpredictable path. His painting Idyll (1927), with its blend of abstract shapes and jazz-age color, shows a continued exploration outside the strict confines of Surrealism.

Stylistic Shifts and Controversial Figuration

The period following his Surrealist involvement saw Picabia embrace yet another stylistic turn, often referred to as his "Monsters" period. These works featured heavily outlined, somewhat grotesque figures, often depicted in dramatic or theatrical poses. This phase reflected a renewed interest in figurative representation, albeit filtered through his characteristic sense of irony and distortion.

Throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, Picabia's style continued to fluctuate dramatically. He moved between abstraction and figuration, often adopting styles that seemed deliberately kitsch or academic, challenging conventional notions of "good taste." This constant shape-shifting baffled critics and alienated some former admirers, but it was central to Picabia's artistic philosophy – a refusal to be pinned down or confined to a single signature style.

Perhaps the most controversial phase of his career occurred during the German Occupation of France in World War II. Living in the South of France, Picabia produced a series of paintings based on photographs found in popular erotic and glamour magazines, including pin-ups. These works, rendered in a slick, pseudo-academic style, depicted idealized female nudes and portraits.

These paintings provoked strong reactions. Some saw them as a cynical betrayal of avant-garde principles, a descent into commercial kitsch. Others interpreted them as a complex commentary on representation, desire, and the debasement of culture during wartime – a final, ironic gesture from the aging provocateur. Picabia himself offered little explanation, adding to the ambiguity. His political stance during the Occupation also drew criticism later, as while he expressed disdain for Nazism, he was perceived by some as having been too accommodating or passive under the Vichy regime.

Late Works, Legacy, and Influence

After the war, Picabia returned to Paris and, surprisingly, to abstraction. His late abstract works are characterized by minimalist compositions, often featuring dots or simple geometric forms against monochrome backgrounds. These paintings possess a stark, meditative quality, a stark contrast to the exuberance and complexity of much of his earlier output. They suggest a final stripping away, a return to fundamental painterly concerns.

His health declined in his later years, and he suffered from arteriosclerosis, which eventually hindered his ability to work. Francis Picabia died in Paris in 1953, leaving behind a legacy as complex and multifaceted as his art.

Picabia's interactions with other major artists were crucial to his development and to the broader narrative of modern art. His complex relationship with Pablo Picasso involved early shared exhibition spaces, followed by divergent paths but maintained dialogue and perhaps rivalry. His deep friendship and collaboration with Marcel Duchamp were fundamental to Dadaism on both sides of the Atlantic. The infamous anecdote of Picabia and Duchamp being mistaken for members of the notorious Bonnot Gang while driving a fast car in 1912 captures their shared rebellious spirit and embrace of modernity. His collaborations and subsequent breaks with figures like Tristan Tzara and André Breton defined key moments in the histories of Dada and Surrealism. His support from writers like Guillaume Apollinaire helped cement his early reputation.

Though sometimes overshadowed by contemporaries like Picasso or Duchamp, Picabia's influence has proven durable. His relentless questioning of artistic conventions, his embrace of irony and paradox, his use of appropriation (as seen in the pin-up paintings), and his stylistic promiscuity anticipated many concerns of postmodern art. Artists like Sigmar Polke and Andy Warhol, with their own engagements with popular culture and stylistic shifts, can be seen as inheritors of Picabia's challenging spirit.

Picabia in Museums Worldwide

Today, Francis Picabia's works are held in the collections of major museums around the globe, attesting to his significance in the history of modern art. Key institutions include:

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

The Art Institute of Chicago

The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Centre Pompidou (Musée National d'Art Moderne), Paris

The Musée National Picasso-Paris

Tate, London

The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

The Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin

These collections showcase the remarkable breadth of his oeuvre, from early Impressionist works to Cubist experiments, iconic Dada machines, enigmatic Transparencies, controversial figurative paintings, and late abstractions.

A Perpetual Motion Machine

Francis Picabia remains a fascinating and often contradictory figure. He was an artist perpetually in motion, driven by a restless intellect and a desire to constantly reinvent himself and his art. He embraced contradiction, celebrated inconsistency, and used humor and provocation as tools to dismantle artistic and societal norms. From the delicate landscapes of his youth to the aggressive machinery of Dada, the layered dreams of Surrealism, and the stark simplicity of his final works, Picabia traversed the landscape of modern art like no other, leaving an indelible mark as its ultimate chameleon and provocateur. His refusal to settle, his constant challenging of boundaries, ensures his continued relevance in understanding the complexities and possibilities of art in the modern era.