Ernest Karl Eugen Koerner stands as a notable figure within the German art landscape of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in 1846 and passing away in 1927, Koerner carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a painter associated with the Berlin School. He was celebrated as a gifted colorist, renowned for his evocative depictions of architectural interiors and captivating indoor scenes, often imbued with a sense of poetic atmosphere achieved through his masterful handling of light and color. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents of his time, particularly the European fascination with the "Orient" and the enduring appeal of architectural grandeur.

Early Life and Artistic Grounding

Ernest Karl Eugen Koerner entered the world on March 11, 1846, in Stibbe, located in the province of Posen, then part of Prussia (now Zdbowo, Poland). His artistic journey eventually led him to Berlin, which became his primary base of operations and the city where he would ultimately pass away in 1927. While specific details of his early training are not fully elaborated in all sources, it is typical for artists of his caliber during this period to have undergone formal academic instruction. He likely honed his skills at one of the prominent German art academies, possibly even the prestigious Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, which was a central institution for artistic education and exhibition in the German capital.

His establishment in Berlin placed him at the heart of a vibrant, albeit often academically conservative, art scene. This environment, dominated by figures associated with the Academy and historical painting, would have shaped his early career. However, Koerner developed a distinct focus that set him apart: a profound interest in capturing the essence of architectural spaces, not merely as static records, but as environments alive with history, light, and atmosphere. He became known as a key representative of the Berlin School, a term often used to describe the realistic and often detailed style prevalent in the city during the latter half of the 19th century.

The Painter of Architecture and Light

Koerner's reputation rests significantly on his exceptional ability to render architectural interiors. He possessed a deep understanding of structural forms and decorative details, but his true genius lay in his capacity to translate these elements into paintings filled with mood and luminosity. He was particularly drawn to the majestic and historically rich architecture of Spain and the Middle East. His canvases often transport the viewer into the intricate halls and courtyards of iconic structures.

Among his most favored subjects were the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain, and the Alcázar of Seville. These Moorish architectural marvels, with their complex tilework, ornate arches, and dramatic interplay of light and shadow filtering through courtyards and windows, provided fertile ground for Koerner's artistic vision. He didn't just document these spaces; he interpreted them, using color harmonies and contrasts, along with carefully managed light effects, to evoke a sense of wonder, tranquility, or even melancholic beauty. His approach was less about photographic accuracy and more about conveying the feeling of being within these historic walls.

His technique primarily involved oil painting on canvas. While oil on canvas was standard, the source material notes this as a point of interest, perhaps highlighting his specific application or the richness he achieved. He worked meticulously, building layers of color to create depth and vibrancy. His skill as a "colorist" was paramount; he understood how different hues could define form, suggest temperature, and contribute to the overall emotional resonance of a scene. Light, whether the bright sunlight of Andalusia or the softer, more diffuse light within ancient temples, was always a key protagonist in his compositions.

Journeys to the Orient

Like many European artists of the 19th century, Koerner was captivated by the allure of the "Orient"—a term then used broadly to encompass North Africa, the Middle East, and the Ottoman Empire. He undertook significant travels to these regions, seeking inspiration and firsthand experience of the landscapes, cultures, and, crucially for him, the architecture that fascinated Western audiences. These journeys were instrumental in shaping his subject matter and cementing his reputation as an Orientalist painter.

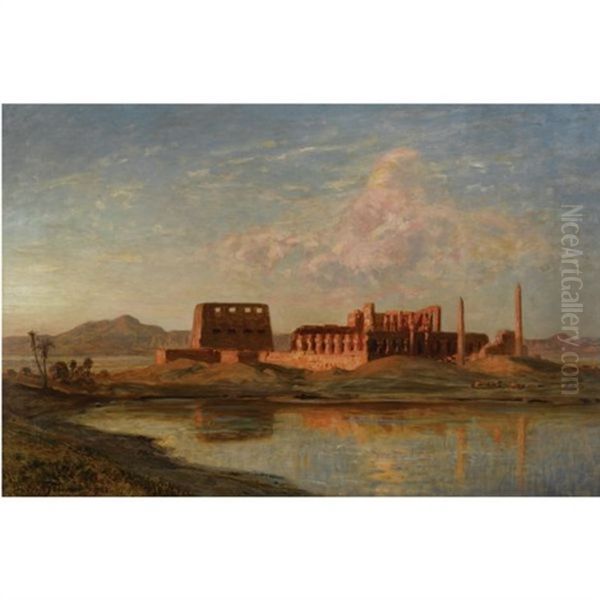

His travels took him to Egypt, a land whose ancient monuments held immense appeal for the European imagination. The colossal temples, enigmatic pyramids, and the vibrant life along the Nile provided a wealth of subjects. Works stemming from his Egyptian travels include depictions of famous sites like the Temple of Karnak, showcasing his ability to convey the sheer scale and weathered grandeur of Pharaonic architecture under the intense Egyptian sun. He also painted scenes reflecting archaeological interest, such as a piece titled Pyramid Excavation, tapping into the contemporary fascination with Egyptology.

Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire, was another key destination. The city's unique position straddling Europe and Asia, its magnificent mosques, bustling bazaars, and scenic waterways offered a different kind of exoticism. Koerner captured views of the Golden Horn, the famous inlet of the Bosphorus, often featuring iconic structures like the Süleymaniye Mosque in the background. These paintings demonstrate his keen eye for atmospheric effects, depicting the haze over the water, the silhouettes of minarets against the sky, and the interplay of light on the city's architecture. His travels provided the authentic details and sensory impressions that lent credibility and evocative power to his Orientalist works.

Notable Works

Several specific paintings stand out as representative of Ernest Koerner's oeuvre and artistic concerns. The Temple of Karnak is a prime example of his Egyptian subjects, likely focusing on the monumental scale and intricate details of the vast temple complex near Luxor. Such works allowed him to explore themes of ancient history, decay, and the enduring power of monumental architecture, all rendered with his characteristic attention to light and texture. This particular work has been exhibited in institutions like the Dahesh Museum of Art in New York, which specializes in 19th and early 20th-century academic art.

The Golden Horn Before the Süleymaniye Mosque, Constantinople captures the unique atmosphere of Istanbul. This painting likely combines a panoramic view of the waterway with the imposing silhouette of one of the city's most famous imperial mosques. It showcases his ability to handle complex cityscapes and waterscapes, integrating architectural elements into a broader atmospheric context. A similar work, titled Altın Boynuz, Istanbul, 1910 (Golden Horn, Istanbul, 1910), was exhibited at the prestigious Great Berlin Art Exhibition (Große Berliner Kunstausstellung), indicating its significance during his lifetime.

Another mentioned work, Pôr-do-sol (Sunset), suggests his interest extended to landscape painting, likely infused with the same sensitivity to light and color seen in his architectural pieces. Sunsets, with their dramatic light and color shifts, would have provided an ideal subject for a painter known as a colorist. Furthermore, Koerner is known to have created works depicting the Red Sea and other general Egyptian Scenes, broadening his Orientalist portfolio beyond specific landmarks. His dedication extended even to monumental work, such as a significant wall painting created for a historic church cemetery in Berlin, which underwent restoration in 2007, attesting to its perceived importance.

Style and Influences

Ernest Koerner's artistic style is best understood as rooted in the academic traditions of the Berlin School, characterized by careful draftsmanship, detailed rendering, and a generally realistic approach. However, he transcended mere technical proficiency through his emphasis on color and atmosphere. His designation as a "colorist" points to his sophisticated use of palette to create mood and define space, moving beyond simple local color to explore the effects of light and reflection.

While firmly established before the rise of radical modernism, Koerner's work reflects certain sensibilities associated with German Romanticism, particularly the interest in exotic locales, historical grandeur, and the evocation of sublime or poetic feelings. His focus on light can also be seen in the context of broader 19th-century interests in optics and atmospheric effects, shared by movements ranging from the Barbizon School to Impressionism, although Koerner's style remained distinct from these.

The mention of "Expressionist landscapes" in some descriptions is intriguing. Given his primary period of activity, it's unlikely he was an Expressionist in the vein of Die Brücke artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (whom the source explicitly distinguishes from Koerner). It's more probable that some of his later landscapes, or perhaps his handling of color and form in certain works, exhibited a heightened emotional intensity or a departure from strict naturalism that could be retrospectively described as proto-Expressionistic or simply highly atmospheric and subjective. His primary contribution remains the fusion of detailed architectural observation with a deeply felt, color-driven atmospheric rendering.

Recognition and Legacy

Throughout his career, Ernest Karl Eugen Koerner received significant recognition for his artistic achievements. He was awarded medals at major international exhibitions, reflecting the high esteem in which his work was held. These accolades include awards from Vienna in 1873, Philadelphia in 1876 (likely the Centennial Exposition), Melbourne in 1889, and Berlin (sources mention both 1891 and 1918, possibly referring to different awards or medals from the recurring Great Berlin Art Exhibitions). Such honors were crucial markers of success for artists operating within the established academic system of the time.

Furthermore, Koerner enjoyed the support of influential patrons, including German Emperors Wilhelm I and Wilhelm II. Royal patronage was highly prestigious and provided artists with commissions, financial stability, and enhanced status. Wilhelm II, in particular, was known for his interest in the arts, favoring works that projected German power and cultural achievement, as well as subjects like marine painting (supporting artists like Carl Saltzmann) and historical scenes, though Koerner's detailed architectural views also found favor.

Koerner's paintings were exhibited regularly, notably at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, a major annual event in the German art calendar. His works entered significant public collections, ensuring his legacy endured beyond his lifetime. While the source mentions the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum, which often collect paintings, drawings, and prints from this period, the claim regarding the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York seems less likely given MoMA's focus, unless they hold prints or works on paper. Regardless, his presence in major institutions like the Met and British Museum confirms his historical importance. He remained active in Berlin until his death in 1927.

Context: The Berlin Art Scene and Contemporaries

Ernest Koerner worked during a dynamic period in German art, particularly in Berlin. The city was the capital of the newly unified German Empire (from 1871) and a burgeoning metropolis. The official art scene was largely dominated by the Academy and figures like Anton von Werner, known for his historical paintings celebrating Prussian and German history, and the highly respected Realist Adolph Menzel, whose detailed depictions of historical events and contemporary life set a high standard. Koerner's meticulous architectural paintings fit within this climate of detailed realism, yet his focus on atmosphere and exotic subjects offered a different flavor.

While Koerner pursued his specific interests, other artistic currents were emerging. German Impressionism found prominent exponents in Berlin with artists like Max Liebermann, Lesser Ury, and later Lovis Corinth (who bridged Impressionism and Expressionism). These artists often focused on modern urban life, landscapes, and portraiture with a looser brushwork and greater attention to fleeting light effects, contrasting with Koerner's more detailed style. Walter Leistikow, another contemporary, focused on moody landscapes of the Brandenburg region and was instrumental in founding the Berlin Secession in 1898, an organization challenging the dominance of the academic establishment – a movement Koerner does not seem to have been part of.

In the broader German-speaking world, other major figures defined the era. In Munich, Franz von Lenbach was a celebrated portrait painter. Symbolism exerted influence through artists like Arnold Böcklin (Swiss-German) whose mythological scenes were widely known. In Vienna, the lavish historical and decorative style of Hans Makart was highly influential. Within the specific genre of Orientalist painting, Koerner can be compared to other German artists like Gustav Bauernfeind, who also traveled extensively in the Middle East and created highly detailed architectural and genre scenes. Koerner's work thus exists within a rich tapestry of overlapping and diverging artistic trends, from academic realism and historical painting to Impressionism, Symbolism, and Orientalism.

Conclusion

Ernest Karl Eugen Koerner was a distinguished German painter whose career successfully navigated the established art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He developed a specialized and highly regarded niche, focusing on the depiction of architectural interiors and Orientalist scenes. His mastery lay in his ability to combine meticulous attention to architectural detail with a profound sensitivity to light and color, creating works that were both informative and deeply atmospheric.

Through his travels to Spain, Egypt, and Constantinople, he brought back visions of distant lands that captivated European audiences, contributing significantly to the Orientalist genre. His paintings of the Alhambra, Karnak, and the Golden Horn remain compelling examples of this practice. Honored with awards, supported by royalty, and represented in major collections, Koerner achieved considerable success in his lifetime. While perhaps not a radical innovator in the mold of the emerging modernists, his work represents a significant achievement within the traditions of late 19th-century realism and colorism, leaving behind a legacy of beautifully rendered architectural portraits imbued with a unique poetic light.