Introduction: Capturing the Valois Court

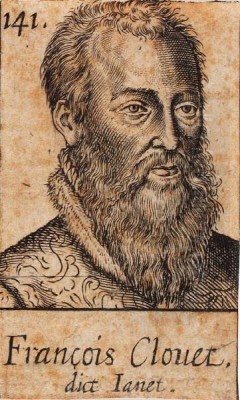

François Clouet stands as one of the most significant and accomplished painters of the French Renaissance. Active during the mid-16th century, he served as the principal court painter to a succession of French monarchs, leaving behind an invaluable visual record of the Valois dynasty during a tumultuous and culturally rich period. Inheriting the mantle from his equally talented father, Jean Clouet, François developed a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail, psychological acuity, and aristocratic elegance. His portraits and miniatures defined the image of French royalty and nobility for generations, blending influences from Northern Europe and Italy into a uniquely French artistic expression. His work provides not only artistic delight but also a crucial window into the personalities, power dynamics, and fashions of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born likely between 1520 and 1522, possibly in Tours or its environs where his father was active, François Clouet grew up immersed in the world of art. His father, Jean Clouet (c. 1480–c. 1541), was himself a highly respected painter, likely of Flemish origin, who had established himself as a leading portraitist at the French court under King Francis I. It was within his father's workshop that François received his foundational training, learning the techniques of drawing, miniature painting, and oil portraiture that were the hallmarks of the Clouet studio.

The elder Clouet's style, marked by sharp observation, subtle modeling, and a certain Northern European precision, undoubtedly formed the bedrock of François's artistic education. The family name itself suggests roots in the Low Countries, and this heritage likely contributed to the emphasis on detailed realism that would characterize both father and son's work. François absorbed these lessons diligently, mastering the craft required to capture not just a likeness, but the very texture of fabrics, the glint of jewels, and the subtle nuances of human expression. This rigorous apprenticeship prepared him to eventually assume his father's prestigious role.

Appointment as Court Painter

Following Jean Clouet's death around 1541, François Clouet stepped into his father's considerable shoes. Records indicate that he officially inherited his father's position as peintre et valet de chambre du roi (painter and valet de chambre to the King) under Francis I. This was a significant appointment, placing him in the direct service of the monarch and granting him privileged access to the highest echelons of French society. The position came with a salary and status comparable to what his father had enjoyed, confirming the court's confidence in his abilities.

This appointment marked the beginning of a long and distinguished career serving the French crown. As court painter, Clouet's primary responsibility was to create official portraits of the royal family and prominent members of the aristocracy. These images served multiple purposes: they were tools of statecraft, exchanged as diplomatic gifts; they recorded lineage and succession; and they projected an image of power, refinement, and stability. François Clouet proved exceptionally adept at fulfilling these demanding requirements, quickly establishing his own reputation distinct from his father's.

Service to Later Monarchs

François Clouet's tenure as court painter extended beyond the reign of Francis I. He continued to serve successive Valois kings, including Henry II, Francis II, and Charles IX. This continuity of service across several reigns underscores his adaptability and the enduring appeal of his artistic style. Perhaps his most significant patron during this later period was Catherine de' Medici, the powerful wife of Henry II and mother to the subsequent three kings. Clouet produced numerous portraits of Catherine and her children, capturing their changing appearances and roles over several decades.

His service involved more than just easel painting. As indicated by court records, Clouet was also involved in designing ephemeral decorations for court festivities, creating emblems and possibly designs for coinage or medals, and, significantly, preparing death masks. He is documented as having made the death masks for both Francis I and Henry II, which were likely used to create funeral effigies – a task requiring both technical skill and sensitivity. This diverse range of activities highlights the multifaceted role of a principal court artist during the Renaissance.

Artistic Style and Technique: A Synthesis of Traditions

François Clouet's art represents a sophisticated fusion of different European artistic currents, adapted to the specific tastes of the French court. While grounded in the meticulous realism inherited from his father and rooted in the Northern European tradition, exemplified by masters like Jan van Eyck or Hans Holbein the Younger, his work also incorporates elements of Italian Renaissance and Mannerist aesthetics.

Precision and Detail: A defining characteristic of Clouet's style is his extraordinary attention to detail. He rendered facial features with remarkable precision, capturing individual likenesses with uncanny accuracy. This extended to the depiction of clothing, jewelry, and accessories. The intricate patterns of lace, the sheen of silk and velvet, the sparkle of gemstones, and the fine strands of hair are all rendered with painstaking care. This meticulousness lends his portraits an almost tangible quality.

Elegance and Linearity: Despite the intense realism, Clouet's portraits possess a distinct elegance and refinement. His figures often have a smooth, polished finish, and his compositions are typically balanced and harmonious. He employed a clear, decisive line to define forms, contributing to the clarity and formal structure of his work. While conveying psychological presence, his portraits maintain a sense of aristocratic reserve and decorum appropriate for their subjects. This linearity contrasts with the softer sfumato often associated with Italian artists like Leonardo da Vinci.

Subtle Modeling and Color: Clouet's use of light and shadow is generally subtle, aimed at modeling form clearly rather than creating dramatic chiaroscuro effects seen in the work of artists like Caravaggio (though Caravaggio belongs to a later period). His modeling creates a sense of volume and three-dimensionality without sacrificing the clarity of detail. His color palettes are often rich but controlled, featuring deep blacks, vibrant reds, and luminous skin tones, contributing to the overall impression of stately elegance.

Psychological Insight: Beyond capturing external appearances, Clouet subtly conveyed the personality and inner state of his sitters. Through careful attention to gaze, posture, and minute facial expressions, he hinted at the intelligence, ambition, melancholy, or authority of figures like Catherine de' Medici or Charles IX. This psychological depth elevates his work beyond mere official documentation.

Influence of Mannerism: Particularly in his later works, one can detect the influence of Italian Mannerism, perhaps absorbed through exposure to Italian artists working at Fontainebleau like Rosso Fiorentino and Primaticcio, or through knowledge of works by painters like Bronzino or Pontormo. This is visible in the elongated proportions, the sophisticated poses, and the cool, polished surfaces found in some of his portraits, adding a layer of stylized artificiality to the underlying realism.

Key Masterpieces: Icons of the French Renaissance

François Clouet's oeuvre includes several paintings that have become iconic representations of the French Renaissance court. These works showcase his technical mastery and his ability to capture the essence of his powerful sitters.

Portrait of Francis I: While his father Jean created the most famous images of Francis I earlier in his reign, François likely painted portraits of the king in his later years. A notable example, often attributed to him and dated around the 1540s, is housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. It presents a mature king, still projecting authority but perhaps showing the weight of his reign.

Portrait of Henry II: Clouet served Henry II extensively. Various portraits and drawings exist, depicting the king in formal attire or armor. His involvement in creating Henry II's death mask after the king's fatal jousting accident in 1559 is also a significant, albeit somber, part of his royal service. The mask itself, or related works, can be found in collections like the Louvre.

Portrait of Catherine de' Medici: Clouet painted Catherine de' Medici at various stages of her life. A famous portrait in the Louvre shows her in mourning attire, likely after the death of Henry II. It captures her formidable presence and political acumen, her dark clothing contrasting sharply with her pale, composed face and watchful eyes. This image powerfully conveys the determination of the Queen Mother who navigated France through decades of religious conflict.

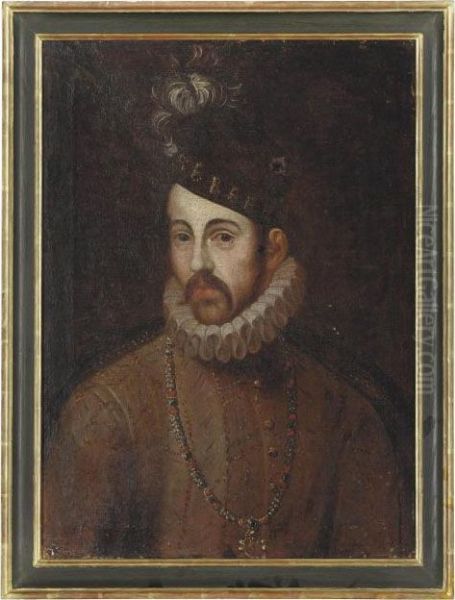

Portrait of Charles IX: Clouet created several important portraits of the young King Charles IX. A full-length portrait (c. 1566) in the Louvre and another version in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, depict the king with an air of youthful authority mixed with a certain fragility. The detailed rendering of his elaborate costume and the directness of his gaze make these compelling images of a monarch ruling during the turbulent French Wars of Religion.

Portrait of Elizabeth of Austria: Considered one of Clouet's supreme masterpieces, the portrait of Charles IX's wife, Elizabeth of Austria (1571), resides in the Louvre. This painting is celebrated for its exquisite detail, delicate handling of paint, and the sensitive portrayal of the young queen. The intricate rendering of her pearl-encrusted gown and the subtle modeling of her features represent the pinnacle of Clouet's refined technique.

Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots: Clouet is associated with portraits of the young Mary Stuart during her time as Queen Consort of France (wife of Francis II). A famous drawing depicting her in white mourning attire (Deuil Blanc) is held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and related paintings exist, capturing the beauty and tragic destiny of the Scottish queen.

Portrait of Diane de Poitiers: The influential mistress of Henry II, Diane de Poitiers, was also depicted by Clouet or his workshop. A painting identified as her, now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., shows her in a manner similar to the Lady in Her Bath, highlighting the blend of portraiture and allegorical themes in his circle.

Lady in Her Bath (Dame au bain): Also housed in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., this enigmatic painting (c. 1571) is one of Clouet's most famous and unusual works. It depicts a noblewoman, sometimes identified as Diane de Poitiers, bathing, attended by a wet nurse and child, with a servant in the background. Combining portrait-like specificity with mythological or allegorical overtones, it reflects the sophisticated and sometimes sensual tastes of the Fontainebleau School, associated with artists like Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio.

Miniatures and Other Works

Beyond large-scale oil portraits, François Clouet excelled in the art of miniature painting. Following the tradition established by his father, he created small, intimate portraits, often set in jeweled lockets or elaborate frames. These required exceptional precision and a delicate touch. Examples, such as miniature portraits possibly depicting members of the royal family like Elizabeth of Austria, showcase his ability to work effectively on a small scale, capturing likeness and detail with remarkable finesse. This skill placed him in the company of other great European miniaturists, such as the later English master Nicholas Hilliard.

His documented work on death masks for Francis I and Henry II further demonstrates his versatility. These masks served a crucial function in royal funerary rites, providing a lifelike image of the deceased monarch for the funeral effigy displayed during the lengthy mourning period. This practice required anatomical accuracy and the ability to capture a serene, idealized likeness even in death.

Furthermore, Clouet's role as valet de chambre likely involved him in a broader range of artistic duties for the court. This could have included designing costumes, advising on decorations for royal entries or festivities, and creating heraldic emblems or designs for tapestries, although specific surviving examples of such work are often difficult to attribute definitively. His diverse skills made him an indispensable artistic figure at court.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

François Clouet worked within a vibrant and complex artistic environment. His primary point of reference was, of course, his father, Jean Clouet, whose style he inherited but also transformed, bringing a greater degree of polish and perhaps a stronger Italianate influence. He was highly regarded by his contemporaries, including the leading poets of the Pléiade group, Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay, who praised his skill in capturing likeness and character.

While direct records of his interactions with other specific painters are scarce, he was certainly aware of the major artistic trends of his time. The French court, particularly under Francis I, had actively imported Italian artists like Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, and Niccolò dell'Abbate to work on the Château de Fontainebleau, establishing a powerful center of Mannerist art. Clouet's work shows an awareness of this sophisticated, elegant style, even as he maintained his grounding in Franco-Flemish realism.

He would have been aware of other portraitists active in France, such as Corneille de Lyon, who worked primarily in Lyon and produced small, intimate portraits with a distinctively direct and less formal style. Internationally, Clouet's work can be compared to that of other leading European portraitists like the Flemish Antonis Mor (Antonio Moro), who worked for the Spanish Habsburgs and whose portraits share a similar aristocratic formality and psychological intensity, or the German Hans Holbein the Younger, whose work at the English court set a high standard for detailed realism and character portrayal. The towering figure of Titian in Venice also set a benchmark for state portraiture across Europe, known for its painterly richness and psychological depth, offering a contrast to Clouet's more linear and detailed approach.

Influence and Legacy

François Clouet's impact on French art was significant and lasting. He, along with his father, essentially established the dominant mode of French court portraiture for the 16th century. His style, characterized by its blend of meticulous detail, elegant linearity, and psychological insight, became the benchmark against which subsequent portraitists were measured. His numerous portraits of the Valois rulers and their courtiers not only served their immediate purpose but also shaped the historical image of these figures for posterity.

His influence can be seen in the work of later French portrait painters, although the tumultuous end of the Valois dynasty and the rise of the Bourbons brought shifts in artistic taste. Artists working in the late 16th and early 17th centuries continued the tradition of detailed, formal portraiture. While perhaps not direct pupils, painters associated with the French court in the subsequent decades operated within the stylistic framework largely defined by the Clouets. The tradition of preparatory drawings, meticulously executed before the final oil painting, was also a key part of the Clouet workshop practice that persisted.

Internationally, Clouet's work represents a distinct national school of Renaissance portraiture, comparable in quality and importance to the contemporary schools of Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and England. His paintings and drawings are prized possessions of major museums worldwide, including the Louvre, the Uffizi, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the British Museum, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. They continue to be studied for their artistic merit, their technical brilliance, and the invaluable historical insight they offer into one of the most fascinating periods of French history.

Personal Life and Anecdotes

Despite his prominence, details about François Clouet's personal life remain relatively scarce. He appears never to have married but, according to his will dated September 1572, shortly before his death, he acknowledged two illegitimate daughters, Diane and Lucrèce. His will reveals a man of considerable means, distributing property and sums of money, indicating a successful career. He named his sister, Catherine Clouet, as an heir as well.

One persistent issue surrounding François Clouet is the difficulty, at times, in definitively distinguishing his work from that of his father, Jean, particularly in the transitional period around 1540. Both artists shared a similar style and technique, and workshop production was common, further complicating attributions. François rarely signed his paintings, relying on stylistic analysis and documentation (when available) for identification. This has led to ongoing scholarly debate about certain works.

The anecdote about his creation of death masks for kings highlights a specific, somewhat macabre, aspect of his court duties, blending artistry with the solemn rituals of monarchy. His documented status as valet de chambre indicates a position of trust and proximity to the king, beyond merely being a painter for hire. He died in Paris in September 1572, not long after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, an event that plunged the French court, which he had so meticulously documented, into further turmoil.

Conclusion: Chronicler of a Dynasty

François Clouet remains a pivotal figure in the history of French art. As the premier portrait painter to the later Valois court, he captured the likenesses of kings, queens, princes, and nobles with unparalleled skill and elegance. He masterfully synthesized the detailed realism of his Franco-Flemish heritage with the sophisticated grace of Italian Mannerism, creating a style that perfectly suited the demands of his royal patrons. His portraits are more than just official records; they are penetrating studies of character, rendered with exquisite technical refinement.

Through his extensive body of work, including oil paintings, drawings, and miniatures, Clouet provided an enduring visual chronicle of the French Renaissance. His art allows us to gaze directly into the faces of those who shaped French history during a critical era of political upheaval, religious conflict, and cultural brilliance. His legacy lies not only in the beauty and craftsmanship of his individual works but also in his defining contribution to the development of portraiture as a major art form in France. François Clouet was, in essence, the visual historian of the Valois dynasty's final, glittering decades.