Introduction: A Versatile Belgian Artist

Frantz Charlet (1862-1928) stands as a significant figure in Belgian art history, a versatile artist whose career spanned painting, etching, and lithography. Born in Brussels, the heart of a rapidly evolving European art scene, Charlet navigated the complex currents of late 19th and early 20th-century art, engaging with Impressionism, Realism, Post-Impressionism, and the evocative allure of Orientalism. His involvement as a founding member of the influential avant-garde group Les XX (Les Vingt) further cemented his place within the progressive art movements of his time. Charlet's legacy is preserved not only through his diverse body of work, held in major Belgian museums, but also through his role in fostering artistic exchange and innovation.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Frantz Charlet was born into the vibrant cultural milieu of Brussels in 1862. His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles (Brussels Royal Academy of Fine Arts). He studied there between 1876 and 1881, immersing himself in the academic traditions that still held sway but were increasingly being challenged by newer artistic ideas filtering in from Paris and beyond. The Academy provided him with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and traditional techniques, skills that would underpin his later explorations into more modern styles.

Seeking broader horizons and exposure to the epicenter of the art world, Charlet subsequently moved to Paris. There, he continued his studies at the Ecole des Arts Libéraux, refining his craft under the tutelage of several noted artists. Among his teachers were figures like Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, known for his large-scale historical and Orientalist paintings, Carolus-Duran, a celebrated society portraitist whose atelier attracted many international students including John Singer Sargent, and Jules Joseph Lefebvre, a prominent academic painter specializing in female nudes and portraits. This Parisian training exposed Charlet to both established academic practices and the burgeoning modern art movements, shaping his artistic sensibilities.

Embracing Impressionism and Light

During his time in Brussels and Paris, Charlet, like many artists of his generation, became receptive to the revolutionary ideas of French Impressionism. The works of artists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, with their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and painting en plein air (outdoors), offered a compelling alternative to the staid conventions of academic art. Charlet's early work began to reflect these influences, showing a move towards a lighter palette, looser brushwork, and a greater interest in contemporary life and landscape subjects.

His development was significantly nurtured by his close friendship with fellow Belgian artist Théo van Rysselberghe. They shared artistic explorations and travels, mutually influencing each other's paths. While Van Rysselberghe would later become a leading proponent of Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism) in Belgium, inspired by Georges Seurat, Charlet's engagement with Impressionism evolved into a personal style that blended its techniques with elements of Realism and, later, a distinct focus on light that aligned with Belgian Luminism. He became adept at rendering the nuances of natural and artificial light, a characteristic that would remain prominent throughout his career.

Journeys South: The Impact of Spain and Morocco

A pivotal moment in Charlet's artistic journey occurred in 1882 when he embarked on an extensive trip to Spain and Morocco. He traveled alongside his friends Théo van Rysselberghe and the Spanish painter Darío de Regoyos, who provided a link to the Spanish art scene. This journey proved immensely influential, exposing the artists to the rich artistic heritage of Spain and the vibrant, sun-drenched landscapes and cultures of North Africa. They visited major sites, including the Prado Museum in Madrid, where they studied the works of Spanish masters like Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya.

The experience of Morocco, in particular, left an indelible mark on Charlet's art. The intense light, exotic colours, bustling markets, and distinct local customs provided a wealth of new subject matter. This journey fueled a lasting interest in Orientalist themes, a popular genre in 19th-century European art that often depicted scenes from North Africa and the Middle East. Charlet sought to capture the unique atmosphere and visual richness of the region, translating his experiences into paintings filled with light and local colour. This trip significantly broadened his artistic palette and thematic concerns.

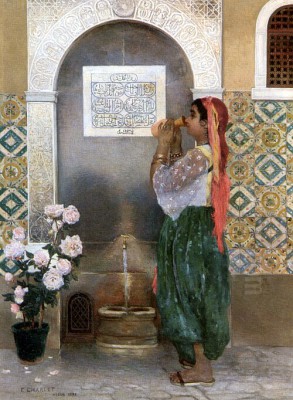

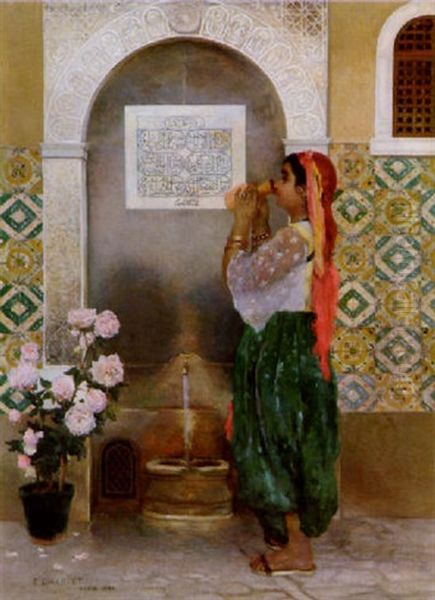

Orientalism in Charlet's Oeuvre

Following his travels, Orientalist subjects became a recurring theme in Frantz Charlet's work. Unlike some academic Orientalists, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose paintings often emphasized ethnographic detail or dramatic historical narratives, Charlet's approach was generally filtered through his Impressionist and Luminist sensibilities. He focused on capturing the visual sensations of North Africa – the play of bright sunlight and shadow, the textures of fabrics and architecture, and the daily life of its inhabitants. His Moroccan and Algerian scenes often feature figures in traditional attire, market settings, or sunlit courtyards.

Works like Algerian Girl Beside a... and A Moroccan Beauty (specific titles often vary or are descriptive) exemplify this aspect of his production. He used vibrant colours and often a broken brushwork technique to convey the shimmering heat and lively atmosphere. These paintings allowed Charlet to explore exotic themes while continuing his experiments with light and colour, distinguishing his work within the broader Orientalist trend. His travels provided authentic source material, lending credibility and immediacy to these depictions.

Les XX: A Crucible of the Belgian Avant-Garde

In 1883, Frantz Charlet became one of the founding members of the Société des Vingt, more commonly known as Les XX (The Twenty). This Brussels-based group, initiated primarily by the lawyer and critic Octave Maus, represented a radical break from the conservative official art establishment in Belgium. Les XX aimed to promote modern, avant-garde art, both Belgian and international, through its annual exhibitions held between 1884 and 1893. It quickly became one of the most important and influential art groups in Europe.

Charlet joined fellow founders such as James Ensor, Fernand Khnopff, Théo van Rysselberghe, Willy Schlobach, Guillaume Van Strydonck, and others in creating a platform free from juries and restrictive academic standards. The group was deliberately eclectic, encompassing a wide range of styles from Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism to Symbolism. This diversity was a hallmark of Les XX, fostering dialogue and experimentation among its members and introducing the Belgian public to groundbreaking international artists.

Charlet's Contribution to Les XX

Within the dynamic environment of Les XX, Frantz Charlet regularly exhibited his work, showcasing his evolving style. His contributions often included landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and his increasingly popular Orientalist scenes. While perhaps not as stylistically radical as James Ensor's expressive and often macabre visions, or as aligned with French Neo-Impressionism as Van Rysselberghe eventually became after seeing Georges Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte exhibited at Les XX in 1887, Charlet represented a strong current of Belgian modernism rooted in Impressionist observation and a sensitivity to light.

The Les XX exhibitions provided Charlet with a prestigious venue to display his art alongside leading international figures invited by Octave Maus. These invitees included Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, James McNeill Whistler, and Auguste Rodin. Participating in these shows placed Charlet at the forefront of the European avant-garde, facilitating exposure and interaction with the latest artistic developments. His involvement underscored his commitment to progressive art movements.

Stylistic Evolution: Realism, Luminism, and Post-Impressionism

Throughout his career, Charlet's style continued to evolve. While Impressionism remained a foundational influence, his work often integrated elements of Realism, particularly in his depiction of figures and genre scenes. He developed a keen ability to capture the quality of light, aligning him with the Belgian Luminist movement, which included artists like Emile Claus. Belgian Luminism, while related to French Impressionism, often placed a greater emphasis on the intense, sometimes almost ethereal effects of light, rendered with vibrant colour, sometimes approaching the intensity of Fauvism in later iterations.

Charlet's paintings, whether depicting the misty coasts of Belgium (like Ostend Beach, c. 1900), the sun-baked landscapes of North Africa, or intimate scenes of children playing (Children Playing by the Sea, The Toy Boat, Children in the Garden), consistently demonstrate his preoccupation with light and atmosphere. His brushwork could vary from relatively tight rendering to looser, more expressive strokes, depending on the subject and desired effect. He skillfully used colour, sometimes employing divisionist techniques learned from Impressionism, to create vibrant and harmonious compositions.

Mastering Light, Color, and Atmosphere

A defining characteristic of Frantz Charlet's art is his mastery in depicting light and colour to evoke specific moods and atmospheres. He was particularly adept at capturing the nuances of coastal light along the Belgian shore, contrasting the often grey, diffused light of the North Sea with the brilliant, sharp sunlight he experienced during his travels in Spain and Morocco. His palette was typically bright and varied, reflecting Impressionist influences, but often deployed with a solidity of form that maintained connections to Realism.

His work Les Lampions (The Lanterns) from 1909 is a notable example of his interest in different light effects, in this case, artificial light. Such scenes allowed him to explore contrasts between warm artificial light sources and the cool tones of twilight or night, showcasing his technical skill and sensitivity to chromatic relationships. Whether painting landscapes, seascapes, portraits, or genre scenes, Charlet consistently used light and colour not just descriptively, but as primary means of conveying emotion and structuring the composition.

Diverse Subjects: From Portraits to Genre Scenes

While landscapes, seascapes, and Orientalist themes form a significant part of Charlet's output, he was also accomplished in portraiture and genre painting. His genre scenes often depict everyday life with sensitivity and charm, frequently featuring children. Works like Two Marken Girls, likely depicting children from the Dutch village of Marken known for its traditional costumes, showcase his ability to capture character and local colour. These paintings often possess an intimacy and observational detail that complements the broader atmospheric effects of his landscapes.

His portraits, though perhaps less numerous or well-known than his other works, would have drawn upon his academic training under portraitists like Carolus-Duran. He applied his understanding of light and colour to the human form, aiming to capture not just a likeness but also the personality of the sitter within their environment. This versatility across different genres underscores the breadth of Charlet's artistic practice.

Later Career: Watercolours and Printmaking

After Les XX disbanded in 1893 (succeeded by La Libre Esthétique, also run by Octave Maus, until 1914), Charlet continued to be active in the Belgian art world. In 1906, demonstrating his ongoing commitment to collaborative artistic endeavours and his interest in diverse media, he co-founded the Société Internationale des Aquarellistes (International Society of Watercolourists). He established this society alongside prominent Belgian artists such as the Symbolist master Fernand Khnopff, the landscape painter Henri Stacquet, and the maritime artist Henri Cassiers. This initiative highlighted the growing appreciation for watercolour as a serious artistic medium.

Beyond painting in oil and watercolour, Charlet was also proficient as an etcher and lithographer. Printmaking offered another avenue for exploring themes and compositions, allowing for wider dissemination of his work. While perhaps less central to his reputation than his paintings, his activity in these graphic media further illustrates his versatility and engagement with different forms of artistic expression available at the time. His prints likely echoed the subjects found in his paintings – landscapes, figures, and possibly Orientalist scenes.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Frantz Charlet's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships. His lifelong friendship with Théo van Rysselberghe was particularly significant, marked by shared travels and early artistic explorations, even as their styles later diverged, with Van Rysselberghe fully embracing Neo-Impressionism. His collaboration with the Spanish artist Darío de Regoyos during their travels also highlights the international connections fostered within the Belgian avant-garde.

Through Les XX, Charlet was in direct contact with the leading figures of Belgian modernism, including the highly individualistic James Ensor, the Symbolist Fernand Khnopff, and sculptors like Constantin Meunier (who occasionally exhibited with the group). He also encountered major international artists invited to exhibit, absorbing influences and contributing to the vibrant artistic dialogue facilitated by the group. While sources mention occasional criticism regarding a perceived lack of originality in Charlet's work compared to some of his more radical contemporaries, his position within these influential circles was undeniable. He navigated these relationships, contributing his own distinct voice, influenced by but not entirely defined by Impressionism or Luminism. Other Belgian contemporaries whose work provides context include landscape painters like Guillaume Vogels and Isidore Verheyden.

Legacy and Reception

Frantz Charlet's work was recognized during his lifetime, finding its way into important public collections. Today, his paintings are held by major Belgian institutions such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA), and the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) in Ghent. His participation in Les XX ensures his place in the annals of European modern art, as the group played a crucial role in challenging academicism and promoting avant-garde movements.

While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame as some of his Les XX colleagues like Ensor or Khnopff, Charlet is regarded as a key figure in Belgian Impressionism and Luminism. His paintings are appreciated for their skillful handling of light and colour, their evocative depictions of Belgian landscapes and coastal scenes, and their engaging exploration of Orientalist themes informed by direct experience. He represents an important facet of the artistic ferment that characterized Belgium at the turn of the 20th century – an artist open to international currents yet retaining a distinct personal and regional sensibility.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Traditions

Frantz Charlet's artistic journey reflects the dynamic transitions occurring in European art during his lifetime. Educated in the academic tradition, he embraced the innovations of Impressionism and developed a personal style characterized by a profound sensitivity to light and colour, often associated with Belgian Luminism. His travels to Spain and Morocco added a significant Orientalist dimension to his work, enriching his thematic repertoire. As a founding member of Les XX, he actively participated in the avant-garde movements that reshaped Belgian and European art. Though sometimes overshadowed by more radical figures, Charlet's consistent output across painting and printmaking, his engagement with artistic societies, and the enduring appeal of his light-filled compositions secure his position as an important and versatile artist within the rich tapestry of Belgian art history. His work serves as a bridge, connecting academic foundations with modern explorations of perception, light, and colour.