Rudolf Grossmann stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century German art. A painter, and perhaps more notably, a master printmaker and illustrator, Grossmann navigated the vibrant and tumultuous artistic landscapes of both Germany and Paris. His work, characterized by a keen observational skill, a fluid linearity, and an innovative approach to graphic techniques, captured the essence of his era, from bustling cityscapes and intimate café scenes to striking portraits of his contemporaries. His engagement with prominent artistic movements and his connections with a wide array of fellow artists place him firmly within the narrative of European modernism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on January 25, 1882, in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, Rudolf Grossmann's artistic journey began not with an immediate immersion in the arts, but with studies in medicine and philosophy in Munich. However, the allure of the visual arts proved stronger. He soon found himself drawn to the creative currents of his time, leading him to pursue formal art training. His initial artistic education took place at the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy), an institution with a long history but one that, by the early 20th century, was seen by some aspiring modernists as somewhat conservative.

Seeking a more progressive and international environment, Grossmann, like many ambitious young artists of his generation, was inevitably drawn to Paris. The French capital was, at this time, the undisputed center of the art world, a crucible of innovation where Impressionism had given way to Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the nascent stirrings of Cubism. In Paris, Grossmann enrolled in the studio of Lucien Simon, a respected French painter known for his genre scenes and portraits, often depicting Breton life. Simon, while not a radical avant-gardist, was a skilled technician and an influential teacher, and his guidance would have provided Grossmann with a solid foundation in figurative art.

The Parisian Crucible: Montparnasse and the Café du Dôme

Grossmann's time in Paris, which extended over several years before the outbreak of World War I, was formative. He became an integral part of the international artistic community that congregated in Montparnasse, particularly around the legendary Café du Dôme. This café was a melting pot for artists, writers, and intellectuals from across Europe and America. Here, Grossmann mingled with a diverse group of creative individuals, absorbing a multitude of influences and forging important artistic relationships.

Among his notable contemporaries in this vibrant milieu were artists like Jules Pascin, the Bulgarian-born painter and draftsman renowned for his sensuous depictions of women; George Grosz, who would later become a scathing satirist of German society; and Hans Purrmann, a German painter who was deeply influenced by Henri Matisse. Walter Bondy, another German artist and a key figure in the "Dômiers" (as the Café du Dôme regulars were known), was also part of this circle. The interactions within this group were characterized by lively debate, shared artistic exploration, and mutual support. Artists like Amedeo Modigliani, with his distinctive elongated portraits, and Moïse Kisling, a Polish-born painter, were also fixtures of the Montparnasse scene, contributing to its dynamic atmosphere. The exchange of ideas in such an environment was crucial for Grossmann's development, exposing him to the latest artistic trends and encouraging him to refine his own visual language.

Artistic Style: Graphic Precision and Expressive Line

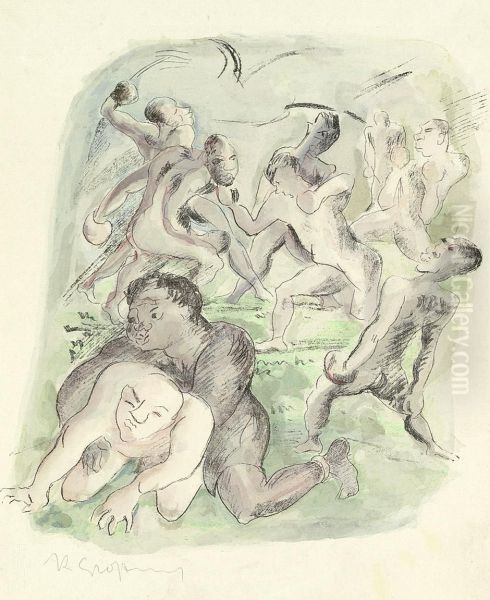

Rudolf Grossmann's artistic output is most celebrated for its graphic quality. He was a prolific printmaker, excelling in etching, drypoint, and lithography. Indeed, he is credited by some sources as an inventor or significant developer of "gel lithography," a variation of the lithographic process, though details on this specific innovation can be elusive. What is undeniable is his mastery over line. His prints often display a remarkable fluidity and spontaneity, capturing movement and character with an economy of means. Whether depicting dancers, boxers, café patrons, or street scenes, his lines are both descriptive and expressive, conveying not just the appearance of his subjects but also their energy and psychological presence.

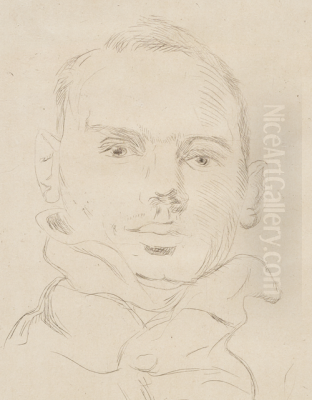

In his paintings, while perhaps less widely known than his prints, Grossmann often employed a style that complemented his graphic work. His canvases could exhibit a concern for capturing light and atmosphere, sometimes with a palette that reflected late Impressionist sensibilities or the more subdued tones favored by some German modernists. He was particularly adept at portraiture, creating insightful likenesses of his contemporaries. His portraits were not merely academic renderings but sought to convey the personality and status of the sitter. The surfaces of his paintings were sometimes noted for their fine texture and luminous paint layers, occasionally executed on handmade wooden panels, suggesting a craftsman's attention to materials.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works are frequently cited as representative of Rudolf Grossmann's oeuvre. His print Der Tanz (The Dance), created around 1923, exemplifies his ability to capture dynamic movement and the social atmosphere of the Roaring Twenties. The figures are often rendered with a sense of immediacy, their gestures and interactions suggesting the rhythm and exuberance of the dance hall. Another significant work, Die Alten (The Old Ones) from 1920, likely showcases a different facet of his observational skills, perhaps a more contemplative or socially aware depiction of age or the human condition in the aftermath of World War I.

His interest in contemporary life extended to various subjects. Boxer (1920) is another notable print, reflecting the popular fascination with the sport during that era. Such a subject allowed Grossmann to explore the human form in motion, capturing the tension and physicality of the boxing match. His portraiture, as mentioned, was a key aspect of his work. The Portrait of Max Liebermann, the eminent German Impressionist and president of the Berlin Secession, is a significant example. Creating a portrait of such a leading artistic figure indicates Grossmann's own standing and connections within the German art world. These works, whether in print or paint, demonstrate his engagement with the world around him, from its leisure activities and sporting events to its notable personalities.

Engagement with Secession Movements and Artistic Associations

Rudolf Grossmann was actively involved in the progressive art movements in Germany. He was a member of the Berlin Secession, a pivotal artists' association founded in 1898 under the leadership of Max Liebermann. The Berlin Secession was established in opposition to the conservative, state-sponsored art establishment, providing a platform for artists working in more modern styles, including German Impressionism and Jugendstil. Other prominent members of the Berlin Secession included Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt, who, along with Liebermann, formed the triumvirate of German Impressionism.

Later, Grossmann also became associated with the Freie Sezession (Free Secession), which emerged in 1914 as a splinter group from the Berlin Secession. This new group, which included artists like Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (though his primary allegiance was to Die Brücke), and Käthe Kollwitz, sought an even more open and less juried exhibition policy, reflecting the increasing diversification of artistic styles in the pre-war and inter-war periods. Furthermore, Grossmann was a member of the Deutscher Künstlerbund (Association of German Artists), founded in 1903, which served as an umbrella organization for avant-garde artists across Germany, advocating for artistic freedom and organizing exhibitions. His participation in these influential groups underscores his commitment to modern art and his active role in shaping the German art scene.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Collections

Throughout his career, Rudolf Grossmann's work was exhibited widely, both in Germany and internationally. He had shows at prominent commercial galleries that championed modern art, such as the Galerie Flechtheim, run by the influential dealer Alfred Flechtheim, and the Galerie Cassirer, owned by Paul Cassirer, who was instrumental in promoting French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in Germany, as well as supporting German artists. These galleries were crucial for the careers of many modern artists, providing them with exposure and sales opportunities.

Grossmann's work gained recognition from public institutions as well. His prints and paintings found their way into numerous prestigious museum collections, a testament to their artistic merit and historical importance. In Germany, his works are held by institutions such as the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Berlin, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich (now part of the Pinakothek der Moderne), and the Hamburger Kunsthalle. Internationally, his art is represented in collections including the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (though this might primarily be for older masters, specific departmental collections could hold modern graphics), the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which houses a major collection of modern and contemporary art, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The presence of his work in such esteemed collections ensures its accessibility for study and appreciation by future generations. Private collectors also valued his work, such as the Carl Vogel collection mentioned in some records.

The Turbulent Interwar Period and Later Years

The period between the two World Wars was one of immense social, political, and artistic ferment in Germany. The Weimar Republic (1919-1933) saw an explosion of artistic creativity, with movements like Expressionism, New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), and Bauhaus flourishing. Grossmann continued to work and exhibit during this time, his art reflecting the changing moods and styles of the era. His graphic work, with its often incisive portrayal of urban life and social types, resonated with the spirit of the times. Artists like Otto Dix and the aforementioned George Grosz were pushing social critique to new extremes, and while Grossmann's work may not have always shared their biting satirical edge, it certainly partook in the era's keen observation of society.

The rise of the Nazi regime in 1933 brought a catastrophic end to this period of artistic freedom. Modern art was branded as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst), and many artists faced persecution, were forbidden to work or exhibit, or were forced into exile. While the provided information does not detail Grossmann's specific experiences under the Nazi regime, it is a critical historical context for any German artist active during this period. Many artists associated with the Secession movements and modernism, including Jewish artists or those with progressive political views, suffered greatly. Max Liebermann, for instance, resigned from the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1933 due to its Nazification and died in relative isolation in 1935.

Rudolf Grossmann passed away in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1941. The circumstances of his later years and death during wartime Germany are not extensively detailed in readily available art historical summaries focusing purely on his artistic output, but it was undoubtedly a dark period for creative individuals in the country.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Rudolf Grossmann's legacy lies primarily in his contributions to German modernism as a skilled draftsman and printmaker. His ability to capture the human figure and the urban environment with a lively, expressive line set him apart. His involvement with the Parisian art scene before World War I connected him to international currents, while his active participation in the German Secession movements and the Deutscher Künstlerbund solidified his place within the national avant-garde.

He was a contemporary of and associated with a remarkable generation of artists. In Germany, beyond those already mentioned like Liebermann, Corinth, Slevogt, Grosz, Beckmann, and Kollwitz, one thinks of the Expressionists of Die Brücke (Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff) and Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke), or individualists like Paula Modersohn-Becker and Emil Nolde. In Paris, the environment he experienced was shaped by giants like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, and a host of other talents. Grossmann's work offers a particular lens through which to view this era, one that often favored graphic immediacy and keen observation over grand theoretical pronouncements.

While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his more radical contemporaries, Rudolf Grossmann's art remains a valuable testament to his skill and his times. His prints, in particular, continue to be appreciated for their technical mastery and their vivid portrayal of early 20th-century life. He was an artist who bridged traditions, absorbing the lessons of Impressionism and academic training while embracing the modern spirit of observation and linear expression. His work provides important insights into the cultural dialogues and artistic developments that shaped European art in the decades leading up to and following World War I. His dedication to the graphic arts, including his potential innovations in lithography, and his sensitive portraiture ensure his enduring place in the annals of German art history.