Franz Ittenbach stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century German art. A painter whose life and work were inextricably linked with a profound religious faith, Ittenbach dedicated his artistic talents almost exclusively to sacred themes. As a prominent member of the later phase of the Nazarene movement and a key artist within the Düsseldorf School of painting, his contributions helped shape the course of religious art in Germany during a period of significant cultural and artistic transformation. His meticulous technique, heartfelt piety, and unwavering commitment to his spiritual ideals produced a body of work that, while perhaps not always aligning with the avant-garde currents of his time, resonated deeply with those who shared his devotional sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Königswinter

Franz Ittenbach was born on April 18, 1813, in Königswinter, a picturesque town nestled at the foot of the Drachenfels hill on the banks of the Rhine River in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. This region, steeped in history and natural beauty, likely provided an inspiring backdrop for the young artist. While detailed records of his earliest childhood and family background are not extensively documented in common art historical surveys, it is clear that his artistic inclinations emerged at a relatively young age. The prevailing cultural atmosphere in the German states during the early 19th century was one of Romanticism, which often emphasized emotion, individualism, and a renewed interest in history, folklore, and spirituality – elements that would later find expression in Ittenbach's mature work.

By the age of nineteen, in 1832, Ittenbach's artistic aspirations led him to enroll at the prestigious Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts (Kunstakademie Düsseldorf). This institution was rapidly becoming one of the most important art schools in Germany, and indeed Europe, attracting students from across the continent and even from America. His decision to pursue formal artistic training here marked the true beginning of his journey as a professional painter, setting him on a path that would define his career and artistic identity.

The Düsseldorf Academy and the Guiding Hand of Wilhelm von Schadow

The Düsseldorf Academy in the 1830s was under the directorship of Wilhelm von Schadow (1788–1862), a pivotal figure in German art. Schadow, himself a painter of considerable renown and a former member of the original Nazarene group in Rome (the Lukasbund, or Brotherhood of St. Luke), had been appointed director in 1826. He brought with him the ideals of the Nazarene movement, which sought a revival of Christian art based on the models of the early Italian Renaissance masters like Raphael, Perugino, and Fra Angelico, as well as earlier German artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger. Schadow's leadership transformed the Düsseldorf Academy into a major center for historical and religious painting, emphasizing strong draftsmanship, clear composition, and morally uplifting subject matter.

Franz Ittenbach not only became a student at the Academy but also benefited from private instruction under Schadow himself. This close mentorship was crucial in shaping Ittenbach's artistic development. Schadow instilled in his students a deep respect for tradition, a rigorous approach to technique, and a belief in the spiritual purpose of art. Ittenbach, with his innate piety, was a receptive pupil to these ideals. The curriculum at Düsseldorf under Schadow would have involved intensive life drawing, copying from Old Masters, and a thorough grounding in Christian iconography and history. It was an environment that nurtured Ittenbach's predisposition towards religious themes.

The Nazarene Spirit: Ideals and Aspirations

To understand Franz Ittenbach fully, one must appreciate the Nazarene movement, of which he became a devoted adherent. The movement originated in Vienna around 1809 when a group of students at the Vienna Academy, including Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) and Franz Pforr (1788–1812), rebelled against what they perceived as the sterile academicism of their training. They sought to revitalize art by imbuing it with genuine religious feeling and by looking to the art of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance for inspiration. They formed the Brotherhood of St. Luke, moved to Rome, and lived a quasi-monastic existence in the abandoned monastery of Sant'Isidoro, earning the somewhat derisive nickname "Nazarenes" due to their anachronistic dress and hairstyles.

Key figures like Peter von Cornelius (1783–1867), Philipp Veit (1793–1877), and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794–1872) were also central to this movement. Their artistic program emphasized clarity of line, bright, unmixed colors (though this evolved), and a focus on narrative and spiritual content over purely aesthetic concerns. While the first generation of Nazarenes established these principles in Rome, their influence spread throughout Germany, particularly through teaching positions. Wilhelm von Schadow was instrumental in bringing these ideals to Düsseldorf, creating a "second wave" or later phase of Nazarene activity. Ittenbach, along with his close friends and fellow students, became key exponents of this later Nazarene style.

Formative Travels and Italian Sojourn

A crucial part of an artist's education in the 19th century, particularly for those interested in historical or religious painting, was the journey to Italy. For the Nazarenes, Italy was not merely a place to study classical antiquity, but a pilgrimage site where they could immerse themselves in the art of the early Christian and Renaissance masters. Franz Ittenbach, following this tradition, embarked on travels that significantly shaped his artistic vision. He journeyed through Germany, absorbing its artistic heritage, often in the company of his close friends and fellow artists Karl Andreas Müller (often referred to as Karl Müller, 1818–1893), Andreas Müller (Karl's brother, 1811-1890, though some sources might conflate or simply refer to Karl Andreas), and Ernst Deger (1809–1885).

Between 1839 and 1842 (some sources extend this to 1843), Ittenbach spent a significant period in Italy. This four-year sojourn was transformative. He resided in Rome, the heart of the Nazarene movement, where he would have encountered the surviving members of the original Brotherhood, such as Friedrich Overbeck, who remained a guiding light for younger religious painters. In Rome, and likely Florence, Ittenbach and his companions diligently studied the fresco techniques of the Old Masters, absorbing the clarity of composition, the serene expressions, and the devotional intensity of artists like Fra Angelico, Perugino, and the young Raphael. This direct engagement with Italian art solidified his commitment to the Nazarene aesthetic and provided him with the technical and spiritual vocabulary that would define his oeuvre. After his Italian studies, Ittenbach spent time working in Munich before eventually settling primarily in Düsseldorf.

The Apollinariskirche Frescoes: A Monumental Collaboration

One of the most significant undertakings for Ittenbach and his Nazarene colleagues from the Düsseldorf School was the commission to decorate the Apollinariskirche (St. Apollinaris Church) in Remagen, near Bonn. This neo-Gothic church, built between 1839 and 1857, was intended as a showcase of revived Christian art. Wilhelm von Schadow, leveraging his influence, secured the commission for his most talented students. Franz Ittenbach, Ernst Deger, Karl Müller, and Andreas Müller were the principal artists entrusted with creating an extensive cycle of frescoes depicting the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. Apollinaris.

The work on the Apollinariskirche frescoes was a monumental task, spanning nearly a decade, with the artists typically working on-site during the summer months. It is reported that the cycle comprised some 69 individual frescoes, containing around 580 figures. This collaborative project was a testament to the Nazarene ideal of artists working together for a common spiritual purpose, much like the medieval guilds they admired. Ittenbach's contribution to this cycle was substantial, and the frescoes are considered a high point of later Nazarene art in Germany. The style is characterized by clear outlines, carefully modeled figures, harmonious color palettes, and a pervasive sense of piety and solemnity. This project cemented Ittenbach's reputation as a leading religious painter.

Beyond the Apollinariskirche, Ittenbach, often in collaboration with Deger and the Müller brothers, was involved in other church decoration projects. For instance, Ernst Deger, Karl Müller, and Andreas Müller also collaborated on frescoes for the chapel of Stolzenfels Castle, near Koblenz, between 1843 and 1851, further demonstrating the close working relationships within this circle. While Ittenbach's direct involvement in every project of his friends isn't always specified, their shared artistic journey and frequent collaborations are a hallmark of their careers.

Artistic Style: Devotional Depth and Technical Precision

Franz Ittenbach's artistic style is a clear reflection of his Nazarene convictions and his meticulous training at the Düsseldorf Academy. His paintings are characterized by a high degree of finish, precise draftsmanship, and a delicate, almost enamel-like application of paint. He favored clear, often bright, but harmoniously balanced colors, avoiding the dramatic chiaroscuro of the Baroque in favor of a more even, gentle light that imbued his scenes with a sense of calm and serenity.

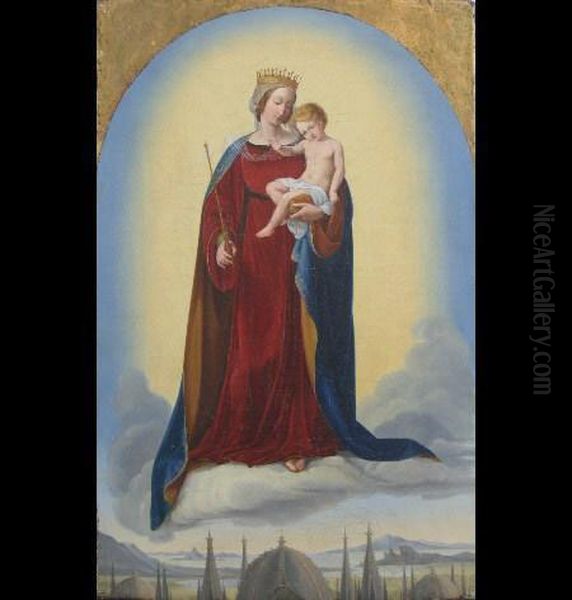

His figures are typically idealized, with sweet, pious expressions, reflecting an inner state of grace and devotion. There is a palpable tenderness in his depictions of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, which became one of his signature themes. While grounded in a careful observation of nature, his art transcends mere naturalism to convey spiritual truths. The compositions are generally balanced and legible, designed to communicate their sacred narratives with clarity and emotional directness. His attention to detail, particularly in drapery, hair, and the rendering of textures, was remarkable, lending an air of preciousness to his works. This meticulousness was not merely for show; it was an act of devotion, a way of honoring the sacred subjects he depicted.

Influences from early Italian Renaissance painters like Raphael, Perugino, and Fra Angelico are evident, as is an affinity with the German tradition of Albrecht Dürer. However, Ittenbach's style also possesses a distinctly 19th-century sensibility, sometimes described as having a certain sentimentality or sweetness that appealed to the devotional tastes of his time but occasionally drew criticism from those who favored a more robust or "masculine" approach to religious art, such as that of Peter von Cornelius.

Signature Themes and Key Works

Ittenbach's oeuvre is overwhelmingly religious. He was known to be a devout Catholic and reportedly refused commissions for mythological or secular subjects that he considered "pagan." His deep personal faith was integral to his artistic practice; it is said that he would prepare himself for painting important works through religious rituals, including confession and Holy Communion. This profound piety shines through in his choice of subjects and their execution.

Among his most celebrated and representative works are numerous depictions of the Madonna and Child. These paintings, often characterized by their gentle intimacy and serene beauty, were highly sought after. An example is his Madonna and Child (many versions exist, one notable from 1859), which showcases his typical smooth finish, delicate modeling, and the tender interaction between mother and infant.

The Holy Family (1861) is another significant work, painted for the private chapel of Prince Liechtenstein near Vienna. This composition would have allowed Ittenbach to explore the dynamics of the sacred family with his characteristic sensitivity and attention to devotional detail.

His contributions to the Apollinariskirche in Remagen remain a cornerstone of his legacy, demonstrating his skill in large-scale fresco painting and his ability to work within a collaborative Nazarene framework. Other works mentioned include paintings for churches in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), indicating the reach of his reputation. Titles like Mother of the World and John the Baptist also appear in accounts of his work, further underscoring his focus on central Christian figures and themes.

His altarpieces and smaller devotional panels were particularly popular, finding homes in churches and private collections across Germany and beyond. The precision of his technique made his works well-suited for reproduction as engravings, which helped to disseminate his imagery and contribute to his popularity among a wider public.

Later Years, Recognition, and Legacy

Franz Ittenbach continued to paint and uphold his artistic ideals throughout his career, remaining based primarily in Düsseldorf. He became a respected member of the artistic community and gained recognition for his contributions to religious art. He was a member of several European art academies and received various honors and medals, attesting to the esteem in which he was held, at least within circles that appreciated his particular brand of devotional art.

However, the art world was changing rapidly in the latter half of the 19th century. The rise of Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet in France and Wilhelm Leibl in Germany, and later Impressionism, brought new aesthetic concerns to the fore, often challenging the traditional hierarchies of subject matter and the idealized approach of academic and Nazarene painting. In this evolving context, Ittenbach's unwavering commitment to a highly finished, spiritually focused art might have seemed increasingly anachronistic to some. The "controversy" sometimes alluded to regarding his work likely stemmed from these shifting artistic tastes; his style could be perceived by some as overly sentimental or lacking in the raw power or social engagement found in other contemporary movements.

Despite this, Ittenbach maintained a steady output and a loyal following. He passed away in Düsseldorf on December 1, 1879, at the age of 66, leaving behind a significant body of work that stands as a testament to his faith and artistic skill.

His legacy is primarily that of a dedicated religious painter who, alongside colleagues like Ernst Deger, Karl Müller, and Andreas Müller, carried the torch of the Nazarene movement into the mid-19th century. He was a key figure in the Düsseldorf School's religious painting tradition, influencing students and contributing to the visual culture of German Catholicism. While his name may not be as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, such as Adolph Menzel or the emerging Impressionists, his work offers a valuable insight into a significant strand of 19th-century art that prioritized spiritual expression and traditional craftsmanship. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their technical excellence, their serene beauty, and the sincere piety they convey. Other painters from the broader Düsseldorf school who explored different genres but shared the same academic environment include landscape painters like Andreas Achenbach, Oswald Achenbach, Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, and historical/genre painters like Carl Friedrich Lessing and Emanuel Leutze (famous for Washington Crossing the Delaware, painted in Düsseldorf). Ittenbach's focused religious path set him apart yet firmly within this influential school.

Ittenbach in the Context of 19th-Century Art

Franz Ittenbach's career unfolded during a dynamic and complex period in European art history. He was a contemporary of Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich (though Friedrich was of an earlier generation, his influence lingered), Realists like Courbet and Jean-François Millet, and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England (e.g., Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais), who shared some of the Nazarenes' interest in pre-Renaissance art and detailed technique, albeit with different thematic and stylistic outcomes.

The Nazarene movement itself, to which Ittenbach belonged, can be seen as a form of Romantic Classicism, looking back to an idealized past for spiritual and artistic renewal. It stood in contrast to the burgeoning interest in contemporary life and social issues that characterized Realism, and later, the focus on fleeting moments and subjective perception found in Impressionism (with artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas). Ittenbach’s steadfast adherence to religious themes and a highly finished, idealized style placed him firmly within the conservative wing of 19th-century art. Yet, this conservatism was, in its own way, a conscious choice and a statement against the increasing secularization and materialism of the age. His art aimed to provide spiritual solace and moral guidance, functions that he believed were paramount for a Christian artist.

Conclusion: An Enduring Devotion

Franz Ittenbach was an artist whose life and work were guided by an unwavering faith and a deep commitment to the ideals of the Nazarene movement. From his formative years at the Düsseldorf Academy under Wilhelm von Schadow to his extensive work in Italy and his significant contributions to monumental projects like the Apollinariskirche frescoes, Ittenbach consistently pursued a vision of art as a vehicle for spiritual expression. His paintings, characterized by their meticulous detail, delicate beauty, and profound piety, offered a serene counterpoint to the more turbulent artistic and social currents of his time.

While art history often privileges innovation and rupture, the steadfast dedication of artists like Ittenbach to established traditions, infused with personal conviction, also plays a crucial role in the rich tapestry of artistic development. He, along with his Nazarene brethren such as Overbeck, Cornelius, Veit, Deger, and the Müller brothers, sought to reinvest art with a sense of sacred purpose. Franz Ittenbach's legacy endures in his beautifully crafted images of Madonnas, Holy Families, and saints, which continue to speak to viewers who appreciate the quiet power of devotional art and the sincere expression of faith. He remains a significant representative of 19th-century German religious painting and a testament to the enduring human quest for the divine through artistic creation.