Johann Friedrich Overbeck stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art. A German painter, he became a principal architect of the Nazarene movement, a group of artists who sought to revitalize art through the lens of profound Christian faith and the study of early Renaissance masters. His life and work offer a compelling narrative of artistic conviction, spiritual devotion, and a quest for purity in an era of significant social and artistic upheaval. This exploration delves into his origins, his pivotal role in shaping a new artistic direction, his distinctive style, his seminal works, and his enduring legacy that rippled through the art world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Lübeck and Vienna

Born on July 3, 1789, in the Hanseatic city of Lübeck, Johann Friedrich Overbeck was fortunate to enter a world of cultural and intellectual richness. His family was well-established and affluent; his father, Christian Adolph Overbeck, was not only a doctor of law and a respected jurist but also a poet, a Pietist theologian, and eventually the mayor of Lübeck. His mother, Eleonora Maria Jauch, hailed from a noble lineage, further situating the young Overbeck within a privileged and educated milieu. This environment undoubtedly fostered his early artistic inclinations and provided him with the support to pursue them.

His artistic journey formally began with early instruction, but the decisive step was his enrollment at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien) in 1806. At the time, the Academy, like many European art institutions, was heavily steeped in the Neoclassical tradition, championed by figures like Heinrich Friedrich Füger, its director. This style, with its emphasis on classical antiquity, idealized forms, and technical polish, was seen by some younger artists as cold, formulaic, and devoid of genuine spiritual or emotional depth.

Overbeck, along with a group of like-minded students, grew increasingly disillusioned with the Academy's rigid curriculum and what they perceived as its superficial approach to art. He found a kindred spirit in Franz Pforr, another young artist who shared his dissatisfaction. Together, they yearned for an art that was more heartfelt, sincere, and imbued with religious meaning. They looked back with admiration to the art of the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, particularly the works of German masters like Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Younger, as well as Italian predecessors such as Fra Angelico, Perugino, and the young Raphael.

This discontent culminated in a pivotal moment in 1809. Overbeck, Pforr, and four other students—Ludwig Vogel, Johann Konrad Hottinger, Joseph Sutter, and Joseph Wintergerst—formed a rebellious artistic cooperative known as the "Lukasbrüder" or the Brotherhood of St. Luke, named after the patron saint of painters. Their manifesto was clear: to reject the prevailing academic classicism and to revive art through a return to Christian piety and the artistic principles of the early masters. They sought an art that was honest, simple, and deeply spiritual, believing that true artistic greatness could only spring from genuine religious conviction. Their actions were a direct challenge to the established artistic order, and in 1810, their perceived insubordination led to Overbeck's expulsion from the Vienna Academy.

The Roman Sojourn and the Birth of the Nazarenes

Undeterred by his expulsion, Overbeck, accompanied by Franz Pforr and other members of the Lukasbrüder, made a momentous decision: they would travel to Rome. Rome, the eternal city, was not only the historical heart of Christianity but also a repository of the classical and Renaissance art they revered. They arrived in 1810, seeking an environment where they could live and work according to their ideals, free from the constraints of the Viennese academic system.

In Rome, the Lukasbrüder found a unique and somewhat monastic setting for their artistic community. They took up residence in the abandoned monastery of Sant'Isidoro a Capo le Case, on the Pincian Hill. Here, they lived a communal life, dedicated to their art and their shared spiritual and aesthetic principles. Their distinctive appearance—often characterized by long hair and attire reminiscent of earlier periods—and their devout, almost ascetic lifestyle, led to the locals mockingly calling them "Nazarenes," alluding to the biblical Nazirites or perhaps to Jesus of Nazareth. The name, initially a term of derision, was eventually embraced by the group and became the identifier for their influential movement.

The Nazarene brotherhood expanded in Rome, attracting other German-speaking artists who shared their vision. Key figures who joined or became closely associated with the group included Peter von Cornelius, Wilhelm von Schadow (son of the sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow), Philipp Veit (stepson of Friedrich Schlegel), Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, and Johann Evangelist Scheffer von Leonhardshoff. Though Franz Pforr, Overbeck's closest early collaborator, died tragically young in 1812, Overbeck emerged as the intellectual and spiritual leader of the Nazarenes. His unwavering commitment to their ideals, his gentle demeanor, and his profound piety made him a central and respected figure.

The Nazarenes aimed to create an art that was both German and Christian, drawing inspiration from the Italian Renaissance but infusing it with a distinctly Northern European sensibility. They emphasized clear outlines, careful modeling, a subdued but often luminous palette, and compositions that conveyed religious narratives with sincerity and emotional depth. They rejected the dramatic dynamism of the Baroque and the perceived paganism of much Neoclassical art, striving instead for a style that was noble, pure, and spiritually uplifting. Overbeck himself converted to Roman Catholicism in 1813, a decision that further solidified his commitment to a religiously infused art and aligned him with the faith of many of the Italian masters he admired. He would remain in Rome for nearly sixty years, until his death, becoming a fixture in the city's artistic and expatriate communities.

Artistic Philosophy and Stylistic Hallmarks

Overbeck's artistic philosophy was inextricably linked to his deep Christian faith. He believed that art's highest purpose was to serve religion and to elevate the human spirit. For him, the technical aspects of painting—drawing, color, composition—were not ends in themselves but means to convey spiritual truths and evoke pious sentiment. This conviction led him to a meticulous and thoughtful approach to his craft.

His style was profoundly influenced by the Italian Quattrocento and early Cinquecento masters. He particularly revered Raphael, not the Raphael of the High Renaissance grand manner, but the earlier, more tender Raphael of the Umbrian period, as well as Raphael's teacher, Perugino. From these artists, Overbeck adopted a clarity of line, a harmonious balance in composition, and a gentle, devotional quality in his figures. He also admired the spiritual intensity and linear precision of Albrecht Dürer, seeing in him a model for a distinctly German Christian art.

A hallmark of Overbeck's style is its emphasis on outline. His drawings are characterized by precise, delicate contours that define forms with clarity and grace. In his paintings, this linear quality often takes precedence over painterly effects or dramatic chiaroscuro. His color palettes are typically clear and bright, though sometimes subdued, avoiding the overtly sensuous or theatrical use of color found in some other Romantic or Baroque traditions. He aimed for a certain purity and simplicity, believing that overly ornate or dramatic effects could detract from the spiritual message of the work.

His compositions are often carefully structured, with a sense of order and balance that reflects his classical training, yet they are imbued with a gentle, lyrical romanticism. Figures are typically idealized, but not in the heroic, antique sense of Neoclassicism. Instead, they possess a serene, often melancholic beauty, their gestures and expressions conveying piety, humility, or quiet contemplation. Overbeck sought to create images that were both aesthetically pleasing and morally edifying, inviting the viewer into a space of spiritual reflection. While some critics, both contemporary and later, found his style somewhat rigid, overly sweet, or lacking in vigor, its sincerity and devotional intensity were undeniable and resonated deeply with many.

Seminal Works and Major Commissions

Overbeck's oeuvre is dominated by religious subjects, ranging from biblical scenes and lives of saints to allegorical representations of Christian virtues and the triumph of faith. He worked in various media, including oil painting, fresco, and drawing, and his influence was disseminated through numerous engravings made after his works.

One of the Nazarenes' first significant collective commissions was the fresco decoration of the Casa Bartholdy in Rome (1816-1817). Jakob Salomon Bartholdy, the Prussian Consul-General, commissioned Overbeck, Cornelius, Schadow, and Veit to decorate a room in his residence with scenes from the biblical story of Joseph. Overbeck's contribution included Joseph Sold by His Brothers (1816/17) and the lunette The Seven Lean Years. These frescoes, with their clear narrative, linear style, and revival of a long-neglected medium, brought the Nazarenes considerable attention and helped to establish their reputation.

Another important collaborative project was the fresco decoration of the Casino Massimo (or Villa Massimo) in Rome (1817-1829), commissioned by Marchese Carlo Massimo. Here, the Nazarenes were tasked with illustrating scenes from great Italian epic poems. Overbeck was assigned Torquato Tasso's Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered). Although he worked on this project for many years, his meticulous and sometimes slow pace meant he completed fewer scenes than some of his collaborators. His frescoes here, such as The Meeting of Godfrey de Bouillon and Peter the Hermit, further demonstrated his commitment to a monumental, narrative art rooted in clear drawing and spiritual content.

Perhaps Overbeck's most ambitious and personal large-scale work is The Triumph of Religion in the Arts, an oil painting he worked on from 1830 to 1840. Originally commissioned for the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, this monumental canvas is an allegorical manifesto of the Nazarene ideal. It depicts a celestial gathering of artists from various periods, from antiquity to the Renaissance, all united under the inspiring influence of Christian faith, personified by the Virgin Mary and Child at the composition's apex. Figures like Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael are prominently featured, alongside architects and sculptors, all paying homage to the divine source of artistic inspiration. The painting is a visual summation of Overbeck's belief in the sacred mission of art.

Other notable works include:

Italia and Germania (c. 1811-1828): A symbolic representation of the friendship and shared artistic ideals between Italy and Germany, personified by two women in tender embrace. This painting, conceived with Franz Pforr, is a poignant expression of early Romantic sentiment and the Nazarene aspiration to bridge artistic traditions.

The Repentance of St. Francis (or The Rose Miracle of St. Francis, 1829): This work, depicting a key moment in the life of St. Francis of Assisi, showcases Overbeck's ability to convey deep piety and spiritual fervor through serene compositions and delicate rendering.

Christ in the Garden of Olives (various versions, e.g., c. 1833, Hamburg Kunsthalle): A recurring theme in his work, treated with characteristic sensitivity and devotional focus.

The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (1809-1824, Marienkirche, Lübeck): A large canvas destroyed in World War II, but known through studies and reproductions, it was a significant early undertaking.

The Raising of Lazarus: Another biblical scene he depicted, emphasizing the spiritual power of Christ.

The Seven Sacraments: A series of paintings (1857-1862) depicting the sacraments of the Catholic Church, demonstrating his continued dedication to religious themes in his later career.

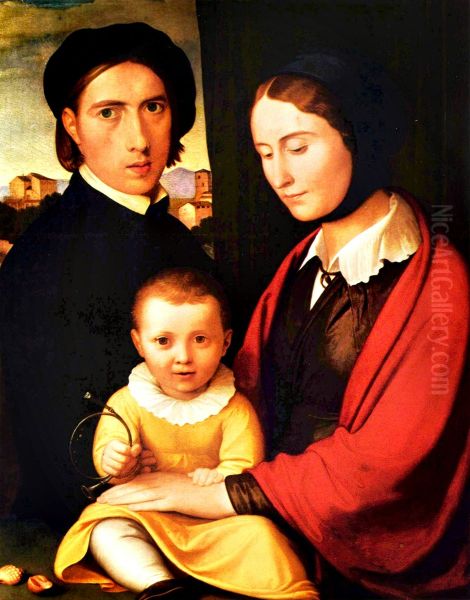

Numerous portraits, including a sensitive Self-Portrait with Wife and Son (1820) and a compelling Portrait of Franz Pforr (c. 1810).

His drawings, often highly finished, were also crucial to his practice and reputation. They reveal his mastery of line and his meticulous preparation for larger compositions.

Collaborators, Contemporaries, and Artistic Climate

Overbeck's career unfolded within a vibrant and often contentious artistic landscape. His closest collaborators were his fellow Nazarenes. The bond with Franz Pforr was foundational, though tragically cut short. Peter von Cornelius was a powerful and ambitious figure within the group, who later achieved great success with monumental fresco cycles in Munich under the patronage of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Wilhelm von Schadow became an influential teacher as director of the Düsseldorf Academy, spreading Nazarene ideals in Germany. Philipp Veit also became a prominent painter and director of the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld was another key member, known for his biblical illustrations and frescoes.

Beyond the core Nazarene group, Overbeck's work and ideals resonated with other artists. In Rome, he was a respected, if somewhat austere, figure. He interacted with artists from various nations who flocked to the city. While the Nazarenes defined themselves in opposition to the dominant Neoclassicism of figures like Jacques-Louis David or the sculptor Antonio Canova, their emphasis on line and clarity sometimes showed an unconscious absorption of classical principles, albeit reinterpreted through a Christian lens.

The broader Romantic movement in Germany, which included painters like Caspar David Friedrich and Philipp Otto Runge, shared some common ground with the Nazarenes, such as a reaction against Enlightenment rationalism and a yearning for spiritual depth. However, Friedrich's intensely personal and often pantheistic landscape mysticism differed significantly from the Nazarenes' focus on historical Christian narrative and figural composition.

Overbeck and the Nazarenes faced criticism from various quarters. Some found their art too archaic, too deliberately imitative of earlier styles, and lacking in originality or contemporary relevance. Others found its piety overly sentimental or dogmatic. The Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, a leading Neoclassical figure in Rome, while reportedly purchasing one of Overbeck's paintings, was generally not aligned with their artistic direction. Even within the German states, their overtly Catholicizing tendencies were sometimes viewed with suspicion in predominantly Protestant regions.

Despite these criticisms, the Nazarenes, with Overbeck as a guiding light, exerted considerable influence. Their revival of fresco painting was significant, and their emphasis on art as a moral and spiritual force found an echo in later movements.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Overbeck remained steadfast in his artistic and religious convictions throughout his long life. He continued to live and work in Rome, a revered elder statesman of a particular vision of art. While the initial fervor of the Nazarene movement dissipated as its members dispersed or developed in different directions, Overbeck remained a symbol of its original ideals. He continued to receive commissions, though perhaps not on the grand scale of some of his former colleagues who had returned to Germany. His later works, such as The Seven Sacraments, show a consistent dedication to his established style and themes.

He passed away in Rome on November 12, 1869, at the age of 80, and was buried in the church of San Bernardo alle Terme. By the time of his death, the European art world was already moving in new directions, towards Realism and Impressionism, which were far removed from Overbeck's spiritualized classicism. For a period, his work, like that of the Nazarenes generally, fell somewhat out of fashion, often dismissed as overly academic or anachronistic.

However, the influence of Overbeck and the Nazarenes proved to be more lasting than it might have seemed in the late 19th century. Their ideas had a notable impact on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in England in 1848. Artists like William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti shared the Nazarenes' admiration for early Renaissance art (before Raphael, in their case), their emphasis on truth to nature combined with symbolic meaning, and their desire to imbue art with serious moral and spiritual content. Ford Madox Brown, closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, had direct contact with Nazarene ideas during his studies.

In the 20th century, there was a scholarly re-evaluation of Overbeck and the Nazarene movement. Art historians began to recognize their importance as a significant manifestation of Romanticism, particularly in its German and religious dimensions. They were seen not merely as revivalists but as artists who grappled seriously with the role of art and faith in the modern world. Overbeck's dedication to his principles, his profound sincerity, and the distinctive, often ethereal beauty of his work earned him renewed respect. He is now understood as a crucial link between the Neoclassical tradition he reacted against and later 19th-century artistic developments that sought alternatives to academicism. His art stands as a testament to a lifelong quest for a "holy art," an art that could nourish the soul and point towards the divine.

Conclusion

Johann Friedrich Overbeck was more than just a painter; he was a visionary who sought to reshape the art of his time according to deeply held spiritual and aesthetic convictions. From his rebellious beginnings in Vienna to his long and productive career in Rome as the leading figure of the Nazarene movement, he pursued an ideal of art rooted in Christian faith and inspired by the purity and sincerity of early Renaissance masters. His emphasis on clear line, harmonious composition, and devotional subject matter created a distinctive style that, while sometimes criticized, exerted a significant influence on his contemporaries and later generations, notably the Pre-Raphaelites. Works like The Triumph of Religion in the Arts and the Casa Bartholdy frescoes stand as powerful statements of his artistic program. In an age of burgeoning industrialization and secularization, Overbeck's unwavering commitment to a spiritually infused art offers a compelling counter-narrative, securing his place as a unique and important figure in the history of European art.