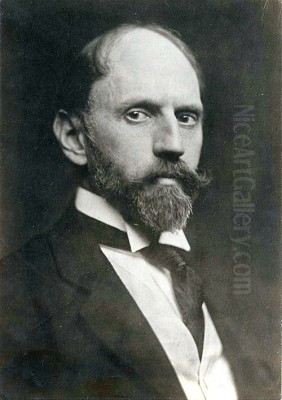

Frederick Judd Waugh stands as a significant figure in American art history, renowned primarily for his powerful and evocative depictions of the sea. An artist of considerable technical skill and broad interests, Waugh captured the dynamic relationship between water and land with a realism and dramatic flair that resonated deeply with the public during his lifetime. Born in Bordentown, New Jersey, on September 13, 1861, and passing away in Provincetown, Massachusetts, on September 10, 1940, his career spanned a period of significant change in the art world, yet he remained largely dedicated to a representational style focused on the majesty and power of the natural world, particularly the ocean.

Artistic Lineage and Early Training

Waugh's immersion in the art world began at birth. He hailed from a family deeply rooted in artistic pursuits. His father, Samuel Bell Waugh, was a noted portrait painter, and his mother, Mary Eliza Young Waugh, was a miniature painter. Furthermore, his older half-sister, Ida Waugh, also became a recognized painter and illustrator. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his innate talent and inclination towards the visual arts from a very young age, providing him with both inspiration and likely his earliest instruction.

His formal art education commenced at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. Founded in 1805, PAFA was a cornerstone of American art education. There, Waugh studied under the influential realist painter Thomas Eakins. Eakins, known for his uncompromising commitment to anatomical accuracy and direct observation, instilled in his students a rigorous approach to depiction. Waugh also studied with Thomas Pollock Anshutz, another key figure at PAFA who continued Eakins's realist tradition. This foundational training grounded Waugh in the principles of academic draftsmanship and realistic representation, skills that would underpin his entire career. Other notable artists associated with PAFA during this era included Mary Cassatt and Cecilia Beaux, highlighting the institution's importance.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Waugh followed a path common for ambitious American artists of his generation: he traveled to Paris. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a private art school famous for accepting foreign students and women, who were often excluded from the official École des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, he received instruction from prominent academic painters Adolphe-William Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Bouguereau, a master of the idealized human form and polished technique, represented the pinnacle of French academic tradition. Robert-Fleury was also a respected history and portrait painter. Studying under these masters further refined Waugh's technical proficiency, exposing him to the highly finished style favored by the Paris Salon.

European Sojourn and Developing Focus

Waugh spent several years in Europe, primarily between Paris and England. He lived for a time on the island of Sark in the English Channel, where the rugged coastline and dramatic maritime weather undoubtedly made a profound impression on him. The constant interplay of waves against cliffs, the changing light on the water, and the sheer force of the sea became subjects of intense observation. This period was crucial in cementing his fascination with marine themes, which would come to dominate his artistic output.

During his time abroad, particularly in London, Waugh engaged in commercial illustration work to support himself. He contributed illustrations to periodicals such as The Graphic and the Illustrated London News. This work, while perhaps driven by necessity, honed his ability to create compelling compositions and narratives quickly. It also kept his observational skills sharp. His European experience occurred during a time when Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, had already challenged academic norms in France, though Waugh's own style would lean more towards realism, albeit often infused with atmospheric light effects reminiscent of Impressionist concerns. He absorbed the technical lessons of his academic training while developing his unique focus on the sea, perhaps drawing inspiration from the legacy of British marine painters like J.M.W. Turner, known for his dramatic and atmospheric seascapes.

Return to America and Rise as a Marine Painter

Around 1907, Waugh returned to the United States, initially settling in Montclair Heights, New Jersey. This marked a turning point in his career, as he began to focus intensely on marine painting. He found abundant inspiration along the Atlantic coast, particularly the shores of Maine and Massachusetts. He quickly gained recognition for his powerful depictions of the ocean, especially scenes featuring large waves crashing against rocky shores under dramatic skies. His ability to convey the weight, movement, and translucency of water was exceptional.

Waugh became a regular exhibitor at major American venues, including the National Academy of Design in New York (where he was elected an Associate in 1909 and a full Academician in 1911), the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His work proved immensely popular with both critics and the public. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the raw energy and sublime beauty of the sea, appealing to a wide audience. His paintings were admired for their technical virtuosity, their dramatic compositions, and their convincing portrayal of nature's power.

Key works from this period solidified his reputation. Paintings like The Roaring Forties and Heavy Surf exemplify his focus on the turbulent ocean. He often depicted the sea in its more tumultuous moods, emphasizing the conflict between water and rock. His approach differed from the often more tranquil seascapes of the earlier American Luminist painters like Fitz Henry Lane or Martin Johnson Heade, aligning more closely, in spirit if not always in style, with the dramatic marine works of Winslow Homer, arguably America's most celebrated painter of the sea. Waugh, along with contemporaries like Paul Dougherty, became a leading figure in early 20th-century American marine painting.

The Signature Style: Realism, Drama, and Light

Frederick Judd Waugh's mature style is characterized by a robust realism combined with a keen sensitivity to atmospheric effects. His primary subject was the sea in motion, particularly the dynamic interface where waves meet the coastline. He meticulously studied wave formations, spending countless hours observing and sketching the ocean's behavior under various conditions. He was fascinated by the physics of water – its transparency, its reflective qualities, its immense power, and the intricate patterns formed by foam and spray.

His paintings demonstrate a profound understanding of marine structure. He rendered the solidity and texture of rocks with convincing detail, contrasting them effectively with the fluidity and energy of the water. His compositions are often dramatic, focusing on the peak moment of a wave's impact or the swirling chaos of receding water. He used strong contrasts of light and shadow to enhance the sense of volume and drama, often depicting scenes under bright sunlight, stormy skies, or the ethereal glow of moonlight. Silver and Gold, one of his most famous works, perfectly illustrates his skill in capturing the play of light on water, creating a shimmering, almost magical effect.

While fundamentally a realist, Waugh was not immune to the influences of Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and color. He often employed a vibrant palette and paid close attention to the way light fractured and reflected on the water's surface. However, unlike the Impressionists who often dissolved form in favor of capturing fleeting moments of light, Waugh maintained a strong sense of structure and solidity in his work. His paintings possess a tangible quality, conveying the physical presence and immense power of the ocean. His technique involved both direct observation, making sketches and studies outdoors, and careful execution in the studio, allowing him to combine accuracy with artistic interpretation.

World War I and Naval Camouflage

Waugh's artistic skills found an unexpected application during World War I. He became involved in the development and application of naval camouflage for the U.S. Navy. Working within the Submarine Defense Association and later under the direction of artist Everett L. Warner in the Navy's Design Section, Waugh contributed significantly to the "dazzle camouflage" system. This system did not aim to hide ships but rather to confuse enemy observers, particularly those on submarines, about the vessel's exact type, size, speed, and heading, making it difficult to target accurately with torpedoes.

Dazzle camouflage involved painting ships in complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting colors. The designs were intended to break up the ship's form and create optical illusions. Waugh, with his keen understanding of form, light, and perspective, was well-suited to this task. He designed camouflage schemes for numerous transport ships and other vessels. It is reported that his designs were highly effective; according to some accounts, only one ship painted with a Waugh-designed scheme was lost to enemy action where the camouflage itself was deemed a contributing factor to the sinking. This wartime contribution highlights Waugh's versatility and his ability to apply artistic principles to practical, life-saving purposes. Other artists, like the British marine painter Norman Wilkinson, were also pioneers in this field.

Versatility Beyond the Waves: Fantasy and Design

While best known for his marine paintings, Frederick Judd Waugh was an artist of diverse talents and interests. He occasionally ventured into other genres, including landscape painting and still life. More distinctively, he explored themes of fantasy and imagination. He created a series of whimsical paintings illustrating a fantasy world populated by small, gnome-like creatures for his book The Clan of Munes, published in 1916. These works reveal a playful and imaginative side to his artistic personality, contrasting sharply with the dramatic realism of his seascapes.

He also painted allegorical and mythical subjects, such as The Knight of the Holy Grail (circa 1912), demonstrating an interest in narrative and symbolism that extended beyond the purely naturalistic depiction of the sea. His versatility extended to decorative arts and design as well. He designed architectural elements, including an altar for St. Mary of the Harbor Church in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He also worked with metals, designing objects in silver and copper, showcasing his skill in three-dimensional form and craftsmanship. This breadth of activity places him in the company of other versatile artists and illustrators of the era, such as Howard Pyle or N.C. Wyeth, who moved between fine art, illustration, and sometimes design.

His artistic legacy also continued through his family. His son, Coulton Waugh (1896–1973), became a well-known artist in his own right, particularly recognized as a painter, cartoonist (famous for the comic strip Dickie Dare), and author of books on cartooning and instructional art.

Later Years in Provincetown and Enduring Popularity

In his later years, Waugh spent much of his time in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a burgeoning art colony at the tip of Cape Cod that attracted numerous artists drawn to its unique light and coastal scenery. Figures like Charles Hawthorne had already established influential art schools there. Provincetown provided Waugh with continued inspiration for his marine subjects, although he also maintained a studio in New York City. He continued to paint prolifically and exhibit widely throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

His popularity remained remarkably consistent. For five consecutive years, from 1934 to 1938, he won the Popular Prize at the Carnegie Institute International Exhibitions in Pittsburgh. This unprecedented achievement underscored the public's enduring affection for his dramatic and accessible seascapes, even as modernist movements like Abstract Expressionism were beginning to emerge. His work offered a powerful connection to the natural world that many viewers found deeply satisfying. His paintings entered numerous important public collections during his lifetime and after, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery of Art, and even the White House collection.

Critical Assessment and Place in Art History

Art critics during Waugh's lifetime generally lauded his technical skill and the convincing power of his marine paintings. He was praised for his draftsmanship, his understanding of marine dynamics, and his ability to convey the sublime power of nature. His popular success was undeniable, making him one of the most recognized American artists of his time in his chosen genre. He was seen by many as a worthy successor to Winslow Homer in the field of marine painting.

However, viewed through the lens of 20th-century modernism, Waugh's adherence to realism sometimes led to criticism. Some commentators felt his work, while technically brilliant, occasionally prioritized dramatic effect over deeper emotional or intellectual content. Compared to the avant-garde artists who were pushing the boundaries of representation and exploring abstraction, Waugh's traditional approach could seem conservative. Some critics found his work lacked the "essential integrity" or profound spiritual depth found in the work of artists grappling more directly with the complexities of modern life or formal innovation, such as contemporaries exploring different paths like John Singer Sargent with his bravura brushwork or Childe Hassam with his American Impressionism, or even Rockwell Kent who also depicted rugged nature but often with a starker, more symbolic edge.

Despite these critiques, Frederick Judd Waugh occupies a secure place in American art history as a preeminent marine painter. His dedication to capturing the ocean's myriad moods, his technical mastery, and the sheer visual impact of his work continue to impress viewers. He remains celebrated for his ability to translate the power and beauty of the sea onto canvas with unparalleled drama and conviction. His paintings stand as enduring testaments to the enduring allure of the ocean and the artist's lifelong engagement with its formidable presence.

Conclusion: Master of the Crashing Wave

Frederick Judd Waugh's legacy is firmly anchored in his powerful and dramatic depictions of the sea. As an American artist deeply influenced by academic training yet profoundly inspired by direct observation of nature, he developed a distinctive style that captured the dynamic energy of the ocean meeting the shore. His technical brilliance, particularly in rendering the movement and texture of water and rock, combined with his flair for dramatic composition and light, made him exceptionally popular during his lifetime. While not an innovator in the modernist sense, his contributions as a leading marine painter, his versatility across genres including fantasy and design, and his unique wartime service as a camouflage designer mark him as a significant and multifaceted figure in American art. His paintings continue to resonate, offering viewers a compelling vision of the ocean's timeless majesty and power.