Edward Alexander Wadsworth (1889-1949) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century British art. His career, marked by a restless intellect and a distinctive visual language, saw him navigate through some of the most dynamic and transformative movements of modernism. From the explosive energy of Vorticism to the meticulous precision of his later marine still lifes, Wadsworth's art reflects both the turbulent spirit of his times and a deeply personal engagement with form, industry, and the maritime world. His journey from engineering studies to the forefront of the avant-garde, his crucial wartime contributions, and his later, more contemplative works paint a picture of an artist constantly evolving yet consistently dedicated to a unique aesthetic vision.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

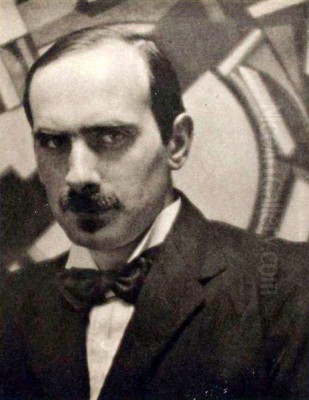

Born on October 29, 1889, in Cleckheaton, West Riding of Yorkshire, Edward Wadsworth was the only child of Fred Wadsworth, a prosperous worsted spinning industrialist, and Hannah (née Smith). His mother tragically died from pneumonia just a week after his birth, and his father later remarried. This industrial background, with its emphasis on machinery, precision, and large-scale operations, would subtly inform his artistic sensibilities throughout his life, even as he initially diverged from the family business path.

Wadsworth's early education took place at Fettes College in Edinburgh. Following this, he pursued engineering studies at the Knirr School in Munich from 1906 to 1907. It was in Munich that his artistic inclinations began to truly flourish. He attended art classes in the evenings, and the vibrant cultural atmosphere of the city, a hotbed of artistic innovation at the time with groups like Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) beginning to form around artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, undoubtedly made an impression. This exposure to continental modernism, even at an early stage, was crucial.

Upon returning to England, Wadsworth's commitment to art solidified. He enrolled at the Bradford School of Art, but his ambition soon led him to London. In 1909, he gained admission to the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art, a veritable crucible of emerging British talent. At the Slade, he was part of an exceptionally gifted generation of students, including Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, William Roberts, and David Bomberg. His time there, under the tutelage of influential figures like Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer, provided him with rigorous academic training, but like many of his contemporaries, he was increasingly drawn to the radical new ideas emanating from continental Europe, particularly Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Futurism, which were being championed in London by critics like Roger Fry.

The Vortex of Modernism: Vorticism

The years leading up to the First World War were a period of intense artistic ferment in London. Wadsworth, with his keen intellect and modernist sympathies, was naturally drawn to the burgeoning avant-garde. He became a pivotal figure in Vorticism, Britain's only significant home-grown modernist movement. Spearheaded by the charismatic and polemical artist and writer Wyndham Lewis, Vorticism sought to create an art that was dynamic, hard-edged, and reflective of the machine age. It was a reaction against the perceived sentimentality of Impressionism and the romantic dynamism of Italian Futurism, aiming for a more static, monumental, and distinctly British form of modernism.

Wadsworth was a founding member of the Rebel Art Centre, established by Wyndham Lewis in 1914 as a breakaway group from Roger Fry's Omega Workshops. He was also a signatory to the Vorticist manifesto, published in the first issue of their radical magazine, BLAST, in July 1914. BLAST, with its aggressive typography and provocative content, aimed to "blast" away the perceived complacency of Edwardian culture and "bless" the new energies of the modern world. Wadsworth contributed illustrations and his name to this seminal publication, aligning himself firmly with Lewis, Ezra Pound (the American poet who coined the term "Vorticism"), and fellow artists like Frederick Etchells, Jessica Dismorr, William Roberts, Helen Saunders, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and Jacob Epstein.

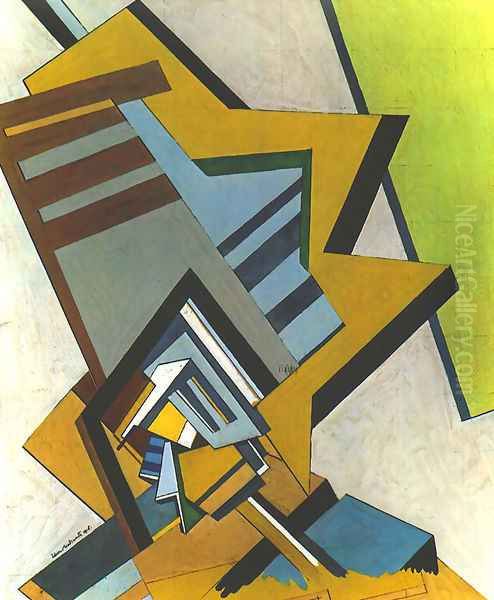

His Vorticist works, such as Abstract Composition (1915) and Short Flight (c. 1914), are characterized by their strong geometric forms, angular lines, and a sense of compressed energy, often drawing inspiration from industrial landscapes, machinery, and urban environments. These pieces demonstrate a clear understanding of Cubist fragmentation and Futurist dynamism, yet they possess a distinct Vorticist clarity and structural rigor. Wadsworth's engineering background likely contributed to his affinity for these precise, almost architectural compositions. He also produced a remarkable series of Vorticist woodcuts, including Typhoon (c. 1915-16) and Rotterdam (1914), which translated the movement's aesthetic into a powerful graphic medium. These woodcuts, with their stark black and white contrasts and dynamic interplay of forms, are among the most compelling expressions of Vorticist principles.

Wartime Service and Dazzle Camouflage

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 profoundly impacted the Vorticist movement, scattering its members and redirecting their energies. Wadsworth enlisted in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) in 1917. His artistic skills and understanding of abstract form found an unexpected and highly practical application: the design of "Dazzle Camouflage" for Allied shipping.

Dazzle camouflage, largely developed by the marine artist Norman Wilkinson, was not intended to make ships invisible, but rather to confuse enemy U-boat commanders about a ship's exact course, speed, and range. This was achieved by painting vessels in complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting, often jarring, colours. Wadsworth, stationed in Bristol and later Liverpool, supervised the application of these schemes to hundreds of ships. His Vorticist training, with its emphasis on bold, abstract design, made him exceptionally well-suited for this task.

His experiences during this period are vividly captured in his iconic painting Dazzle-ships in Dry Dock at Liverpool (1919), now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada. This large-scale oil painting depicts dazzle-camouflaged ships undergoing maintenance, their fragmented, brightly coloured forms creating a disorienting yet visually stunning spectacle. The work is a powerful synthesis of his Vorticist aesthetic and his wartime experiences, transforming a utilitarian military application into a compelling work of modern art. It remains one of the most enduring images of British art from the First World War era. Other works from this period, such as the woodcut Drydocked for Scaling and Painting (1918), further explore these themes.

Post-War Explorations: Precisionism and the Nautical World

After the war, Vorticism as a cohesive movement did not revive. The optimism and revolutionary fervor of the pre-war avant-garde had been tempered by the brutal realities of conflict. Wadsworth, like many artists, sought new directions. He briefly returned to the industrial landscapes of his native Yorkshire, producing a series of stark, powerful drawings and prints of the Black Country, such as Blast Furnaces (1919). These works, while representational, retain a Vorticist sense of monumental structure and stark geometry.

A significant shift occurred in the early 1920s when Wadsworth began to work extensively in tempera, an ancient medium using egg yolk as a binder for pigment. Tempera allowed for a meticulous, precise application of paint and produced a clear, luminous finish, which suited his evolving aesthetic. He also increasingly turned to nautical themes, inspired by his wartime experiences and a lifelong fascination with the sea, ships, and maritime paraphernalia.

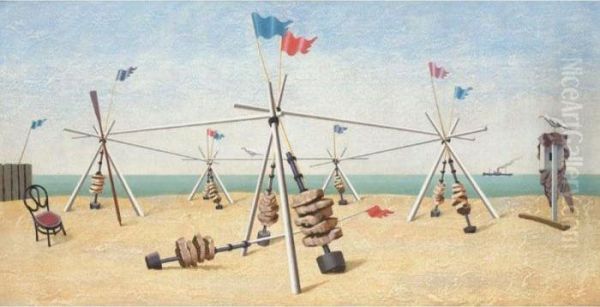

His paintings from the 1920s and 1930s often depict meticulously rendered still lifes of shells, nautical instruments, fishing floats, and other maritime objects, frequently set against coastal backdrops or abstracted seascapes. Works like Regalia (1928), a striking tempera painting of nautical flags and instruments, showcase his mastery of this medium and his ability to imbue everyday objects with a sense of mystery and formal elegance. There is a distinct clarity and almost crystalline quality to these works, sometimes described as a form of Precisionism or Magic Realism. Artists like Charles Sheeler in America were exploring similar avenues of sharp-focus realism.

Wadsworth's compositions from this period are often characterized by a sense of stillness and order, a stark contrast to the dynamic energy of his Vorticist phase. Yet, there is also an underlying strangeness, a hint of the surreal, in the juxtaposition of objects and the dreamlike quality of some of his seascapes. This aligns him with a broader trend in European art of the 1920s, often termed a "return to order," but Wadsworth's interpretation was uniquely his own, filtered through his maritime preoccupations.

Unit One and Surrealist Affinities

In the 1930s, Wadsworth continued to refine his distinctive style. He became associated with Unit One, a group of British artists, architects, and designers founded in 1933 by Paul Nash. Unit One aimed to promote and define contemporary British art, encompassing both abstract and Surrealist tendencies. Its members included Nash, Wadsworth, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, John Armstrong, Edward Burra, Tristram Hillier, the architect Wells Coates, and the critic Herbert Read.

Wadsworth's inclusion in Unit One highlights the dual nature of his work during this period. While his meticulous realism might seem at odds with pure abstraction or overt Surrealism, his compositions often possessed a disquieting, dreamlike quality and a formal rigor that resonated with the group's aims. His paintings of abstracted coastal landscapes and enigmatic still lifes, such as The English Channel (1934) or Visibility Moderate (1934), demonstrate a subtle engagement with Surrealist ideas, particularly in their creation of unsettling atmospheres and unexpected juxtapositions, reminiscent in spirit, if not style, to the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico or the precise dreamscapes of Salvador Dalí or René Magritte, though Wadsworth's approach was always more restrained and grounded in observable reality.

He exhibited with Unit One and contributed to their publication, Unit 1: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, edited by Herbert Read. This period saw him further develop his highly polished tempera technique, creating works of extraordinary detail and luminosity. His fascination with maritime subjects remained paramount, but he explored them with an increasing sense of abstraction and formal invention.

Later Career and Legacy

Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, Wadsworth continued to produce his meticulously crafted tempera paintings. The Second World War, unlike the first, did not see him directly involved in military service in the same way, though the conflict undoubtedly cast a shadow. His art, however, largely maintained its focus on the timeless themes of the sea and its accoutrements, offering perhaps a sense of stability and enduring beauty in a world once again consumed by conflict.

His later works, such as Bronze Ballet (1940) and Aspects of a Headland (1948), show a continued exploration of complex compositions, often featuring interlocking forms and a sophisticated play of light and shadow. The precision of his technique remained remarkable, and his ability to create a sense of depth and atmosphere within his highly structured designs was undiminished. He also continued to produce woodcuts, maintaining his mastery of this demanding medium.

Edward Wadsworth was also a member of the New English Art Club (NEAC), a more traditional exhibiting society that had, in its earlier days with figures like Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, been a progressive force. His membership indicates his connection to a broader spectrum of the British art world beyond the avant-garde circles.

Wadsworth died relatively young, on June 21, 1949, in Bayswater, London, at the age of 59. Some sources suggest complications from amoebic dysentery, possibly contracted during his earlier travels. His death marked the loss of a unique voice in British modernism.

Edward Wadsworth's legacy is that of an artist who successfully bridged several key movements and styles. He was a crucial participant in the radical Vorticist experiment, a pioneer in the artistic application of camouflage, and a master of a highly individualised form of precise, often surreal-tinged, realism. His work is held in major public collections, including Tate Britain, the Imperial War Museum, the National Gallery of Canada, and many others. While perhaps not as widely known as some of his contemporaries like Paul Nash or Ben Nicholson, his contribution to British art is undeniable. He brought an engineer's precision, a modernist's eye for form, and a romantic's love for the sea to his diverse and compelling body of work, leaving behind a legacy of striking imagery that continues to fascinate and intrigue. His art serves as a testament to the complex interplay of industrial modernity, avant-garde aesthetics, and enduring maritime traditions in the first half of the 20th century.