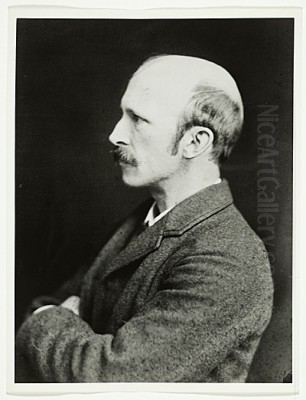

Abbott Handerson Thayer stands as a uniquely compelling figure in the annals of American art. Born on August 12, 1849, in Boston, Massachusetts, and passing on May 29, 1921, in Dublin, New Hampshire, Thayer was far more than a painter of exquisite, ethereal figures. He was a devoted naturalist, an influential teacher, a pioneer in the study of protective coloration in animals, and a significant, if sometimes controversial, contributor to the development of military camouflage. His life and work offer a fascinating intersection of Gilded Age aesthetics, scientific inquiry, and a profound, almost spiritual connection to the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Abbott Handerson Thayer was the son of Dr. William Henry Thayer, a respected country doctor, and Ellen Handerson Thayer. His early years were spent in the relatively rural setting of Keene, New Hampshire, an environment that undoubtedly fostered his lifelong passion for nature. From a young age, Thayer exhibited a keen interest in the outdoors, particularly in ornithology and taxidermy. He would spend countless hours observing birds and animals, meticulously studying their forms and behaviors. This early immersion in the natural world would become a foundational element of his artistic and scientific pursuits.

His formal artistic training began modestly. While attending the Chauncy Hall School in Boston, he received guidance from Henry D. Morse, an amateur painter who specialized in animal subjects. Morse recognized Thayer's burgeoning talent and encouraged his detailed observation of wildlife. Even in these formative years, Thayer's dedication was apparent; he was already producing accomplished animal portraits, demonstrating a precocious ability to capture the essence of his subjects. His passion for art and nature grew in tandem, each informing and enriching the other.

Seeking more rigorous instruction, Thayer moved to Brooklyn, New York, in 1867, where he studied at the Brooklyn Art School and later at the National Academy of Design. During this period, he began to establish himself as a painter of animals and landscapes, finding a market for his works that depicted the creatures he knew so intimately. However, the allure of European academic training, then considered essential for any aspiring American artist, soon beckoned.

Parisian Influence and the École des Beaux-Arts

In 1875, Thayer, accompanied by his first wife, Kate Bloede, embarked for Paris, the epicenter of the art world. He enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic art. There, he studied for four years, primarily under Henri Lehmann and Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme, in particular, was a master of meticulous detail and historical subjects, and his rigorous approach to drawing and composition left a lasting impression on Thayer. The emphasis on anatomical accuracy and polished finish, hallmarks of the Beaux-Arts tradition, refined Thayer's technical skills considerably.

During his time in Paris, Thayer formed important friendships with fellow American artists, notably George de Forest Brush and Daniel Chester French. Brush, who would also become known for his idealized figures and Native American subjects, shared Thayer's interest in precise draftsmanship. French, destined to become one of America's foremost sculptors, known for works like the Lincoln Memorial statue, was part of this vibrant expatriate community. These relationships provided intellectual stimulation and camaraderie, crucial for young artists far from home. Thayer also absorbed the broader artistic currents of Paris, including the burgeoning Impressionist movement, though his own work would largely remain rooted in a more traditional, albeit personalized, aesthetic.

Return to America and the Idealized Figure

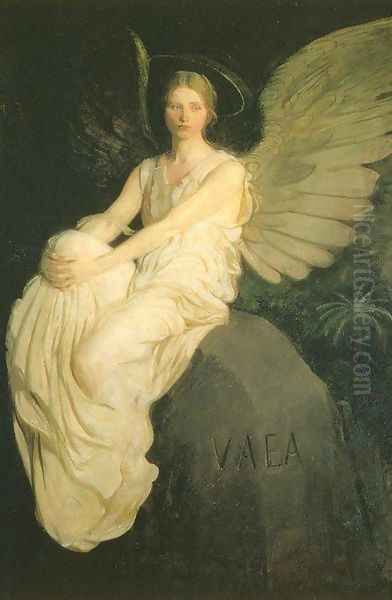

Upon his return to the United States in 1879, Thayer initially settled in New York City, establishing a studio and beginning his professional career in earnest. He painted portraits, landscapes, and animal subjects, gradually gaining recognition. However, it was his development of a particular type of idealized female figure that would come to define his most iconic and celebrated works. These paintings, often featuring his own children—Mary, Gerald, and Gladys—as models, depicted ethereal, angelic beings, embodying concepts of purity, spirituality, and transcendent beauty.

Works such as Angel (1887) and A Virgin (1892-93), now in the Freer Gallery of Art, are prime examples of this phase. In Angel, his daughter Mary is portrayed with majestic wings, her gaze direct yet otherworldly. The painting combines a palpable sense of realism in the figure's rendering with a profound spiritual aura. A Virgin presents his three children as a central, enthroned Madonna-like figure flanked by two attendants, evoking Renaissance altarpieces. These "ideal figures," as they were often called, resonated with the Gilded Age's taste for art that uplifted the spirit and aspired to noble sentiments, drawing comparisons to the work of European Symbolists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

Thayer's approach to these figures was deeply personal. He saw in his children, and in women generally, an embodiment of virtue and spiritual strength. His paintings were not merely decorative; they were expressions of his own deeply held beliefs about the sanctity of innocence and the protective power of beauty. Artists like Thomas Wilmer Dewing, known for his Tonalist paintings of refined women in spare interiors, also explored themes of idealized femininity, though Thayer's figures often possessed a more robust, classical monumentality.

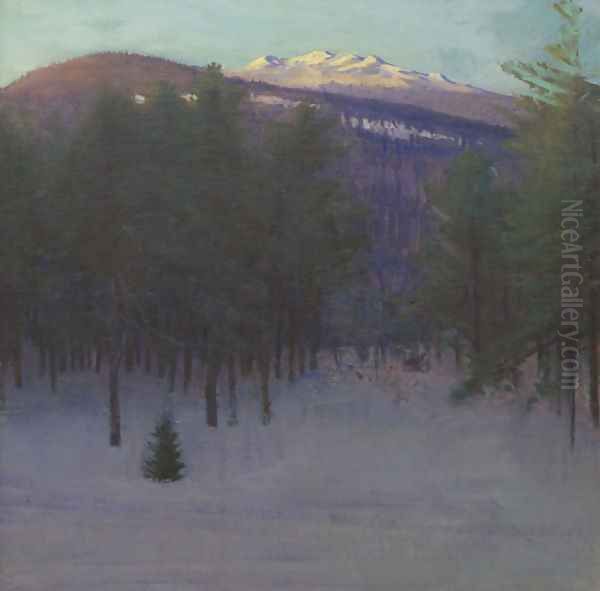

Nature's Palette: Landscapes and Animal Studies

Despite the acclaim for his figural compositions, Thayer never abandoned his profound connection to the natural world. In the late 1880s, seeking respite from city life and a closer connection to nature, Thayer and his family began spending summers in Dublin, New Hampshire, near Mount Monadnock. In 1901, after the tragic death of his first wife, Kate, and his subsequent marriage to their long-time friend Emma Beach, Thayer made Dublin his permanent home. The majestic presence of Mount Monadnock became a recurring and powerful motif in his landscape paintings.

His Monadnock landscapes are characterized by their atmospheric depth, subtle color harmonies, and a sense of timeless grandeur. He painted the mountain in all seasons and at all times of day, capturing its ever-changing moods. These works often possess a Tonalist sensibility, akin to the landscapes of his contemporary Dwight William Tryon, emphasizing mood and poetic effect over literal transcription. Thayer's landscapes were not just picturesque views; they were meditations on the enduring power and spiritual solace found in nature.

His animal paintings also continued throughout his career. Works like Roseate Spoonbills (circa 1900) showcase his exceptional skill in rendering avian subjects with both scientific accuracy and artistic sensitivity. Unlike the purely scientific illustrations of John James Audubon, Thayer's animal paintings often imbued his subjects with a sense of personality and vitality, reflecting his deep empathy for the creatures he depicted. He was a contemporary of other notable American animal painters like Louis Agassiz Fuertes, who also combined artistic talent with ornithological expertise.

The Science of Deception: Thayer's Camouflage Theories

Perhaps Thayer's most unique and far-reaching contribution lay outside the conventional realm of fine art: his pioneering work on the principles of protective coloration in nature and its application to military camouflage. Drawing on his lifelong observations of animals, Thayer, often in collaboration with his son Gerald, developed several key theories about how animals use color and pattern to conceal themselves.

His most significant insight was the principle of "countershading" (or "Thayer's Law"), which posits that the darker upper surfaces and lighter under-surfaces of many animals counteract the natural effects of shadows, making them appear flatter and less conspicuous to predators and prey. He also articulated the concept of "disruptive coloration," where bold, contrasting patterns break up an animal's outline, and "background picturing," where an animal's markings mimic its specific environment.

Thayer passionately advocated for these theories, publishing articles and, with Gerald, the influential book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom in 1909 (revised edition 1918). He conducted numerous demonstrations, often using his own paintings or three-dimensional models, to illustrate how these principles worked. He believed that virtually all animal coloration served a concealing purpose, a view that was, and to some extent remains, controversial among biologists.

With the outbreak of World War I, Thayer saw an urgent application for his theories in military camouflage. He tirelessly lobbied the Allied governments, proposing methods for camouflaging ships, aircraft, and military installations. While his direct influence on official military camouflage policy was complex and sometimes met with resistance, his ideas, particularly regarding countershading and disruptive patterns, undoubtedly contributed to the broader development of camouflage techniques. Artists like Everett Warner, who headed the design section of the U.S. Navy's camouflage unit during WWI, developed "dazzle camouflage" for ships, a concept related to Thayer's ideas about visual confusion, though distinct in its aim to mislead rangefinders rather than achieve invisibility. Thayer's friend, George de Forest Brush, also experimented with camouflage for aircraft.

Controversies and Challenges

Thayer's passionate advocacy for his camouflage theories often led to public debate and controversy. His insistence on the universality of concealing coloration in animals was challenged by prominent figures, including former President Theodore Roosevelt, himself an experienced naturalist. Roosevelt argued that some animal coloration was for display or warning, not concealment, leading to a spirited public exchange of letters and articles.

In the art world, while his idealized figures were widely admired, some critics found them overly sentimental or repetitive. His unconventional painting techniques, which sometimes involved mixing materials like mud into his pigments or using a broom to achieve certain textural effects, also raised eyebrows among more traditional academicians.

Thayer's personal life was marked by periods of intense productivity alternating with bouts of debilitating depression and anxiety, a condition he referred to as the "Abbott pendulum." These mood swings profoundly affected his ability to work and his relationships. The loss of his first wife was a devastating blow, and the responsibilities of raising his children while grappling with his own mental health challenges were immense. His second wife, Emma, provided crucial stability and support during these difficult times. Despite these personal struggles, his dedication to his art and his scientific pursuits remained unwavering.

Personal Life, Character, and Artistic Circle

Thayer was a man of intense convictions and a somewhat eccentric character. He and his family embraced a rustic, unconventional lifestyle in Dublin, New Hampshire. They were known to sleep outdoors year-round, even in the harsh New England winters, believing it beneficial for their health. This deep immersion in nature was integral to his being, fueling both his art and his scientific observations.

He was a dedicated teacher, and his studio in Dublin attracted a number of students who were drawn to his unique vision and passionate instruction. Among his notable pupils was Rockwell Kent, who would become a prominent painter, printmaker, and illustrator, and Richard Sumner Meryman, who painted a well-known portrait of Thayer. Thayer's teaching emphasized direct observation of nature and a deep understanding of form and light.

His circle of friends and patrons included influential figures in the art world. Charles Lang Freer, the founder of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., was a significant patron and admirer, acquiring many of Thayer's most important works, including A Virgin and several angel figures. Thayer also maintained correspondences and friendships with other leading artists of his day, such as John Singer Sargent, whose painterly bravura contrasted with Thayer's more meticulous approach, yet both were towering figures in American art. He was also associated with the "Ten American Painters," a group that seceded from the Society of American Artists, including figures like Childe Hassam and J. Alden Weir, who were pushing American art in new directions, often influenced by Impressionism.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Thayer continued to paint, focusing increasingly on the landscapes of Mount Monadnock and portraits of family and friends. His work retained its characteristic intensity and spiritual depth. He also remained actively involved in conservation efforts, advocating for the protection of birds and natural habitats. His deep love for the natural world translated into a commitment to its preservation, a stance that was ahead of its time.

Abbott Handerson Thayer died at his home in Dublin, New Hampshire, on May 29, 1921, at the age of 71. He left behind a rich and complex legacy. His paintings are held in major American museums, including the Freer Gallery of Art (now part of the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These institutions recognize him as a key figure in American art at the turn of the 20th century.

His contributions to the theory of protective coloration, while debated, were undeniably groundbreaking. He forced both scientists and the public to look at animal coloration in a new way, and his principles of countershading and disruptive patterning have become fundamental concepts in the study of camouflage, influencing fields from evolutionary biology to military strategy and even fashion.

Enduring Influence on Art and Science

Abbott Handerson Thayer's influence extends beyond his own lifetime. His idealized figures, with their blend of realism and spiritual aspiration, contributed to the American Renaissance movement, which sought to create a national art of high moral and aesthetic purpose. Artists like Kenyon Cox, who also championed classical ideals and allegorical figures, shared some of Thayer's artistic aims.

His dedication to teaching nurtured a new generation of artists, and his passionate engagement with the natural world served as an inspiration. While the overtly sentimental aspects of some of his work fell out of favor with the rise of Modernism, there has been a renewed appreciation for his technical skill, his unique vision, and the sheer beauty of his paintings. Artists like Andrew Wyeth, with his meticulous realism and deep connection to specific American landscapes, can be seen as inheritors of a tradition that Thayer, in his own way, helped to shape.

In the scientific realm, while some of Thayer's more sweeping claims about universal concealment have been modified by later research, his core insights into the mechanisms of camouflage remain valid and influential. His work laid an important foundation for future studies in animal behavior, evolutionary biology, and visual perception.

Abbott Handerson Thayer was a man of many facets: a painter of sublime beauty, a meticulous observer of nature, a passionate theorist, and a complex individual. His life's work demonstrates a remarkable synthesis of art and science, driven by an unwavering belief in the interconnectedness of beauty, truth, and the natural world. He remains a testament to the power of singular vision and the enduring impact of an artist who dared to look deeply into the heart of nature and translate its mysteries into both paint and principle.