Frederick McCubbin stands as a colossus in the annals of Australian art history. Born during a period of burgeoning national consciousness, he became a pivotal figure in defining a distinctly Australian artistic vision. As a leading member of the celebrated Heidelberg School, often termed Australian Impressionism, McCubbin dedicated his life to capturing the unique light, landscape, and burgeoning identity of his homeland. His work, ranging from heroic depictions of pioneer life to intimate portrayals of the bush and his own family, continues to resonate deeply, offering profound insights into the Australian experience at the turn of the twentieth century. He was not only a masterful painter but also a dedicated and influential educator, shaping generations of Australian artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Melbourne

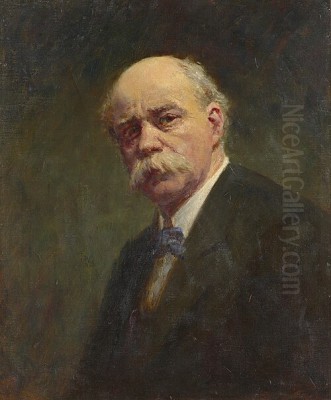

Frederick McCubbin was born in Melbourne, Victoria, on February 25, 1855. He was the third of eight children born to Alexander McCubbin, a baker who had emigrated from Scotland, and Anne McWilliam, who came from an English farming background. Growing up in the bustling colonial city, young Frederick's early life was tied to the family business. He left school at fourteen, around 1869, to work as a clerk for a solicitor, but soon joined his father's bakery.

Despite the demands of the bakery trade, McCubbin's artistic inclinations surfaced early. He began attending evening drawing classes at the Artisans' School of Design in Carlton. This initial training provided a foundation, and his passion for art grew. Alongside his bakery work, he was briefly apprenticed to a coach painter between 1870 and 1875, learning practical skills in paint application, though his aspirations lay in fine art.

His formal art education commenced in earnest when he enrolled at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School in the mid-1870s (sources vary slightly on the exact year, often citing 1871 or later). Here, he studied initially under the drawing master Thomas Clark. Later, he came under the tutelage of the Austrian-born landscape painter Eugene von Guerard, whose detailed, somewhat romanticised style, influenced by the Düsseldorf school, dominated the Melbourne art scene at the time. Von Guerard's meticulous approach likely influenced McCubbin's early, more detailed works.

The NGV School was a crucible for artistic talent. It was here that McCubbin formed crucial friendships that would shape his career and the future of Australian art. Most significantly, he met Tom Roberts, another aspiring artist who would become a lifelong friend and collaborator. Their shared passion and ambition laid the groundwork for future artistic ventures. He also studied under George Folingsby after von Guerard's departure, whose emphasis on tonal values and figure painting offered a different perspective.

The Genesis of Australian Impressionism: Box Hill and the Heidelberg School

The 1880s marked a turning point for McCubbin and Australian art. Tom Roberts returned from studying in Europe in 1885, bringing back fresh ideas about Impressionism and the importance of painting en plein air (outdoors). Inspired, McCubbin, Roberts, and fellow artist Louis Abrahams established an artists' camp at Box Hill, then a rural area east of Melbourne. This marked the beginning of a concerted effort to capture the unique effects of Australian light and landscape directly from nature.

The Box Hill camp became a hub of artistic activity. They were soon joined by Arthur Streeton, a younger artist of prodigious talent who had initially been McCubbin's pupil at the NGV school, and later by Charles Conder, who arrived from Sydney. This core group, often expanding to include others like Walter Withers, Clara Southern, and Jane Sutherland, formed the nucleus of what would later be dubbed the Heidelberg School, named after another area near Melbourne where they subsequently painted.

Their approach was revolutionary for Australia. Rejecting the darker palettes and studio-bound conventions of earlier colonial art, they embraced brighter colours, looser brushwork, and a focus on capturing fleeting moments and atmospheric effects. They sought to depict the Australian landscape not as a European transplant, but on its own terms – its distinctive colours, harsh sunlight, and unique flora. McCubbin, Roberts, Streeton, and Conder were the driving forces behind this movement.

A landmark event was the "9 by 5 Impression Exhibition" held in Melbourne in 1889. McCubbin was a key participant alongside Roberts, Streeton, Conder, and others. They exhibited small, sketch-like works, many painted on cigar box lids measuring approximately 9 by 5 inches, hence the exhibition's name. While controversial at the time, facing criticism from conservative critics like James Smith for their perceived lack of finish, the exhibition is now seen as a seminal moment, boldly asserting the principles of Australian Impressionism and challenging academic conventions.

Capturing the National Narrative: The Bush and the Pioneer Spirit

While deeply engaged with the principles of Impressionism and plein air painting, McCubbin's work often carried a strong narrative and emotional weight, particularly in his depictions of bush life and the pioneer experience. He became known as the painter of the Australian national narrative, exploring themes of hardship, resilience, loss, and the human struggle against the vast, often unforgiving landscape.

One of his earliest masterpieces in this vein is Down on His Luck (1889). Painted around the time of the 9 by 5 Exhibition, it depicts a solitary swagman, or itinerant worker, sitting dejectedly by a small campfire in the bush, his billy can beside him. The mood is melancholic, capturing a sense of isolation and disappointment that resonated with the realities of rural life and economic depression. The painting quickly became, and remains, one of Australia's most iconic images, embodying a particular aspect of the national psyche.

Another powerful work exploring the theme of loss in the bush is A Bush Burial (1890). This sombre painting shows a small group of figures – a grieving husband, a woman comforting him, and a gravedigger – gathered around a freshly dug grave in a clearing. The vastness and indifference of the surrounding bush underscore the human tragedy. McCubbin used his wife Annie and fellow artist Louis Abrahams as models, lending a personal dimension to the scene. It reflects the harsh realities faced by early settlers.

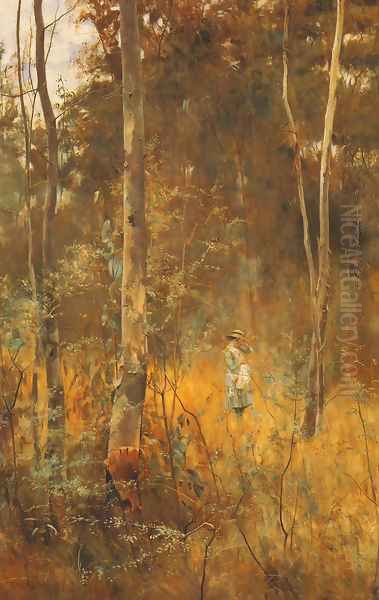

Perhaps McCubbin's most ambitious narrative work is the triptych The Pioneer (1904). This large-scale painting tells a story across three panels. The first panel shows a young pioneering couple arriving in the dense bush, hopeful but facing an untamed wilderness. The central panel depicts them years later, having cleared some land and built a small home, with a child now part of the family. The final panel shows a young man, presumably their son, standing by a grave (implied to be the pioneer's) overlooking a now more developed landscape with a burgeoning city visible in the distance. The Pioneer is a complex meditation on progress, settlement, sacrifice, and the passage of time, becoming a foundational image in the mythology of Australian nation-building.

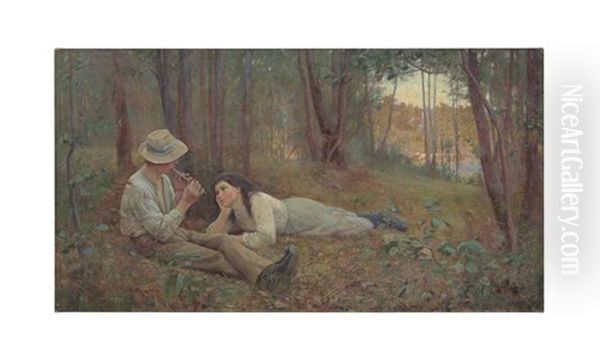

Other significant works exploring bush themes include On the Wallaby Track (1896), depicting a woman with a child resting by a campfire while her husband boils the billy, and Bush Idyll (1893), a more lyrical, slightly controversial work showing a young man playing a pipe to a reclining young woman in a sun-dappled bush setting. These works cemented McCubbin's reputation as a painter deeply connected to the Australian land and its human stories.

A Dedicated Educator and Leader

Beyond his own artistic output, Frederick McCubbin made a profound and lasting contribution to Australian art through his role as an educator. In 1886, he was appointed Drawing Master at the National Gallery of Victoria's School of Design, a position he held with dedication until his death in 1917. He eventually became the head of the Drawing School.

McCubbin was an inspiring and influential teacher. He moved away from the rigid, copy-based methods of earlier instruction, encouraging his students to draw from life and engage directly with their subjects. His own commitment to plein air painting undoubtedly influenced his teaching philosophy. He fostered a supportive environment, nurturing the talents of many students who would go on to become significant artists in their own right. Arthur Streeton is perhaps the most famous example, but many others benefited from his guidance.

His leadership extended beyond the NGV school. McCubbin was actively involved in the Melbourne art community. He was a founding member of the Victorian Artists' Society (VAS) in 1888, formed from the merger of earlier groups, and served as its president multiple times (1902-04, 1908-09, 1911-12). He was also instrumental in the formation of the breakaway Australian Art Association (AAA) in 1912, serving as its inaugural president, reflecting ongoing debates and dynamics within the Melbourne art world.

McCubbin's commitment to fostering Australian art was evident in his advocacy for artists. He supported initiatives like student scholarships and opportunities for artists to study abroad, recognizing the importance of both local development and international exposure. His long tenure at the NGV school provided stability and continuity, shaping the direction of art education in Victoria for over three decades. His influence as a teacher and mentor is a crucial part of his legacy.

Evolution of Style: Embracing Light and Intimacy

While McCubbin is often associated with the heroic pioneer narratives, his artistic style continued to evolve throughout his career, particularly following his first and only trip to Europe in 1907. This visit proved transformative. He travelled to England and France, seeing firsthand the works of the great British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner, whose atmospheric effects deeply impressed him, and the French Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas.

The impact of this European sojourn was immediately apparent in his subsequent work. His palette lightened considerably, embracing brighter, purer colours. His brushwork became looser, more broken, and more expressive, focusing on capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere. The strong narrative element, while not entirely disappearing, often gave way to a more purely visual and sensory engagement with the subject.

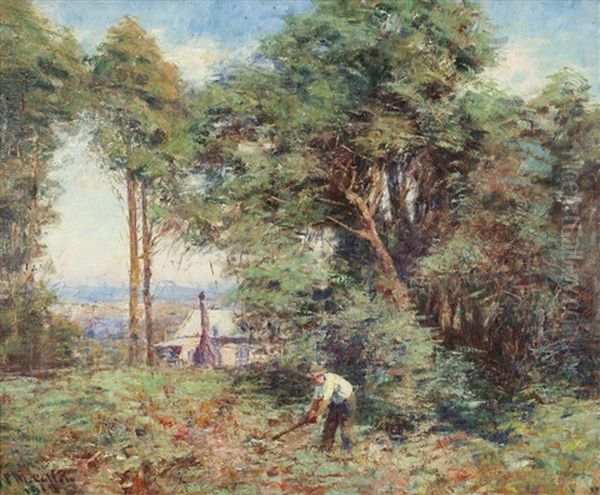

This later style found fertile ground in the landscapes around Mount Macedon, a scenic area northwest of Melbourne where McCubbin and his family moved in 1901, purchasing a property they named 'Fontainebleau'. The lush forests, misty hills, and changing seasons of Macedon provided endless inspiration. Works from this period, such as The Pool, Macedon (c. 1909-10), Winter Sunlight (c. 1908), and Golden Sunlight (1914), showcase his mastery of light and colour, rendering the Australian bush with a newfound vibrancy and lyricism.

His family also became central subjects in his later work. Intimate portraits of his wife Annie and their children, often depicted in the garden or interiors of their Macedon home, reveal a more personal, tender side of his art. Paintings like Violet and Gold (1911) or Princess (depicting his daughter) are imbued with affection and a quiet domesticity, rendered with the same sensitivity to light and colour that characterized his landscapes. Some critics consider these later, more experimental and light-filled works to be the pinnacle of his artistic achievement, showcasing a mature and confident artist exploring the purely painterly possibilities of his medium. Spring Morning (1914) exemplifies this later phase, depicting workers in the Macedon landscape with a focus on light and atmosphere rather than overt narrative.

Interactions, Anecdotes, and Contemporaries

McCubbin's life was interwoven with the artistic community of his time. His close friendship with Tom Roberts was foundational, marked by collaboration, mutual support, and occasional artistic debate. An anecdote relates Roberts critiquing an early McCubbin work, Melbourne Gaol in Sunlight, for lacking "values," prompting McCubbin to refine his technique – a testament to their frank artistic relationship.

His relationships with Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder were also significant. He mentored Streeton and painted alongside both, sharing the camaraderie and artistic exploration of the Heidelberg School camps. While Roberts, Streeton, and Conder eventually spent considerable time overseas, McCubbin remained largely based in Australia, becoming a central, stable figure in the Melbourne art scene.

He existed within a broader network of artists. Earlier figures like the Swiss-born Louis Buvelot had pioneered plein air painting in Victoria before the Heidelberg School, influencing artists like Roberts. McCubbin's teachers, von Guerard and Folingsby, represented the established academic tradition against which the younger generation reacted. Contemporaries in Sydney, like Julian Ashton, led a parallel development of Impressionist ideas. Later landscape painters such as Elioth Gruner and Hans Heysen, while developing their own distinct styles, built upon the foundations laid by McCubbin and the Heidelberg School. Female artists like Jane Sutherland and Clara Southern were integral participants in the Heidelberg School circle, though often faced greater barriers to recognition.

A curious anecdote from his youth suggests an early rebellious streak: he was reportedly dismissed from an early job as a coach painter's apprentice at age 14 for stealing paints, perhaps hinting at his desperation to pursue art. His later career, however, was marked by professionalism and dedication. The controversy surrounding the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition highlighted the challenges faced by artists pushing boundaries. Even his iconic narrative works like Down on His Luck sparked discussion, interpreted not just as artistic statements but as commentaries on social conditions and the emerging national identity.

Enduring Legacy and Critical Evaluation

Frederick McCubbin's legacy is immense and multifaceted. He is universally acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of Australian painting and a central figure in the Heidelberg School, the country's first significant national art movement. His work played a crucial role in shifting the focus of Australian art towards local subjects and landscapes, interpreted through a modern, Impressionist-influenced lens.

His iconic paintings, particularly The Pioneer, Down on His Luck, and A Bush Burial, have become deeply embedded in the Australian cultural consciousness. They are celebrated for their portrayal of the pioneer spirit, the beauty and harshness of the Australian bush, and their contribution to a sense of national identity during the era leading up to and following Federation in 1901. These works continue to be widely reproduced and studied, representing a particular vision of Australia's past.

As an educator, his impact was profound. Through his long tenure at the NGV school, he influenced generations of artists, instilling principles of observation, draughtsmanship, and an appreciation for the local environment. His role in founding and leading key artists' societies further cemented his position as a leader within the artistic community.

Critically, McCubbin's reputation has remained strong, though the appreciation of different phases of his work has evolved. While the narrative paintings secured his popular fame, art historians and critics increasingly recognise the artistic sophistication and painterly freedom of his later works, particularly those produced after his European trip and during his time at Mount Macedon. These works are praised for their lyrical beauty, subtle colour harmonies, and expressive brushwork, demonstrating his continued artistic growth and engagement with international modernism.

Frederick McCubbin died of a heart attack on December 20, 1917, at his home in Mount Macedon, aged 62. He left behind a rich body of work that continues to captivate and inspire. He was more than just a painter of the bush; he was an artist who explored the depths of human experience – resilience, loss, family, and the profound connection between people and place – all set against the unique backdrop of the Australian landscape he knew and loved so intimately. His contribution remains central to the story of Australian art.