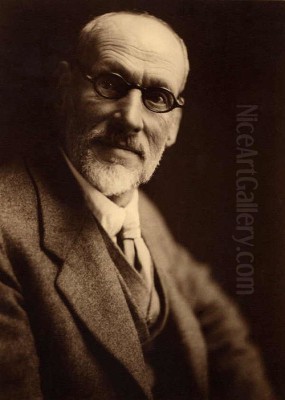

Thomas William Roberts, affectionately known as Tom Roberts, stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Australian art history. Born in Dorchester, Dorset, England, on March 8, 1856, he emigrated with his widowed mother and siblings to Australia in 1869, settling in Collingwood, a suburb of Melbourne. His journey from a young immigrant to becoming a leading force in the Heidelberg School, often termed Australian Impressionism, cemented his legacy. Roberts passed away on September 14, 1931, leaving behind a body of work that profoundly shaped Australia's visual identity.

Roberts was more than just a painter; he was a visionary who sought to capture the unique essence of the Australian continent – its light, its landscapes, its people, and its burgeoning national consciousness. He played a pivotal role in steering Australian art away from purely European conventions towards a style that reflected the local environment and experience. His influence extended through his art, his teaching, and his central role in fostering a community of like-minded artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Upon arriving in Melbourne, the young Roberts initially worked as a photographer's assistant during the day while pursuing art studies at night. He attended the Collingwood and Carlton artisans' schools of design, where he first met Frederick McCubbin, who would become a lifelong friend and key collaborator. Later, both studied at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, learning from artists like Thomas Clark and the influential Swiss-born landscape painter Louis Buvelot, whose plein air (outdoor painting) approach significantly impacted Roberts. The Irish-born painter Eugen von Guérard was another instructor at the Gallery School during this period.

Seeking to further his skills, Roberts returned to London in 1881 to study at the Royal Academy Schools. This period was crucial for his development. He travelled through Europe, notably visiting Spain in 1883 with fellow Australian artist John Peter Russell, where they met Spanish painters Laureano Barrau and Ramon Casas. Exposure to European art movements, including Impressionism and the Aesthetic Movement associated with James Abbott McNeill Whistler, broadened his horizons. He absorbed the emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and painting directly from nature, techniques associated with artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage.

Return to Australia and the Artist Camps

Roberts returned to Melbourne in 1885, brimming with new ideas and techniques. He became a central figure in the burgeoning movement to develop a distinctly Australian style of painting. He reconnected with Frederick McCubbin, and together they sought locations around Melbourne suitable for painting outdoors, directly capturing the unique Australian light and atmosphere.

Their search led them to establish an artists' camp at Box Hill in late 1885. This camp, often considered the first significant locus of plein air painting in Australia, attracted other artists eager to explore these new approaches. Among the key figures who joined them were Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder. Louis Abrahams, another friend and artist, was also part of this early circle. These camps provided not only locations for painting but also fostered camaraderie, intellectual exchange, and the consolidation of shared artistic aims.

Later, the focus shifted to the area around Heidelberg, east of Melbourne. Renting a cottage at Eaglemont, Roberts, Streeton, and Conder, often joined by McCubbin and others, painted some of the most iconic works of the era. The landscapes around Heidelberg, with their rolling hills, winding Yarra River, and distinctive eucalyptus trees bathed in golden light, became synonymous with the movement, eventually lending it the name "Heidelberg School."

The Heidelberg School: Defining Australian Impressionism

The Heidelberg School, flourishing primarily in the late 1880s and 1890s, represented Australia's first major home-grown art movement. While influenced by French Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on light, colour, and capturing transient effects, it developed its own distinct characteristics. Tom Roberts was undoubtedly a leader and organiser within this group.

The artists associated with the Heidelberg School, including Roberts, McCubbin, Streeton, and Conder as the core figures, shared a commitment to depicting Australian life and landscape authentically. They moved away from the darker palettes and romanticised views often seen in earlier colonial art, embracing brighter colours and looser brushwork to convey the harsh sunlight and unique hues of the Australian bush. Other artists associated with or influenced by the school included Walter Withers, Jane Sutherland, Clara Southern, and the sculptor Charles Douglas Richardson.

Their work often carried a nationalistic undertone, celebrating rural labour, pioneering spirit, and the beauty of the Australian environment. They aimed to create images that resonated with the growing sense of national identity in the lead-up to Federation in 1901. Roberts, in particular, focused on themes that helped define this emerging identity.

National Narratives and Iconic Works

Tom Roberts is perhaps best known for his large-scale paintings depicting quintessential Australian scenes, often referred to as his "national narratives." These works aimed to capture the spirit and character of the nation through iconic activities and landscapes.

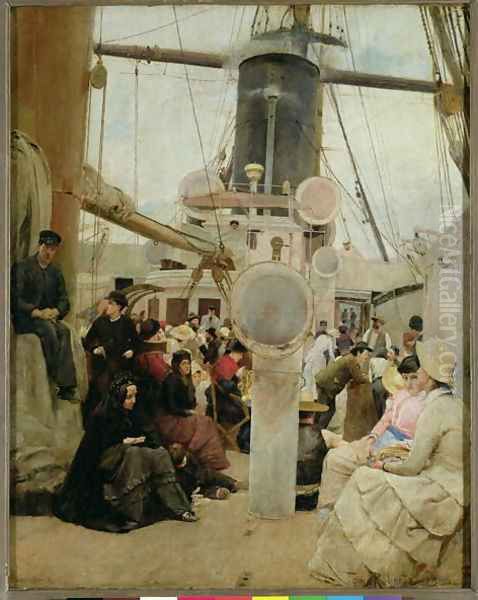

Shearing the Rams (1890) is one of the most famous paintings in Australian art history. Roberts spent considerable time on sheep stations, sketching and studying the shearers at work, to ensure authenticity. The painting depicts the interior of a shearing shed, filled with the energy and toil of the shearers, the golden fleece, and the distinct Australian light filtering through the timber structure. It became an emblem of Australian pastoral life and industry, celebrating manual labour and mateship.

A Break Away! (1891) captures the drama of thirsty sheep stampeding towards water during a drought, with a stockman desperately trying to turn the mob. This dynamic composition conveys the harsh realities and challenges of life on the land, highlighting the relationship between humans, animals, and the often-unforgiving Australian environment.

Bailed Up (1895) depicts a stagecoach hold-up by bushrangers, a theme drawn from Australia's colonial past. Unlike more melodramatic depictions, Roberts presents the scene with a sense of stillness and realism, set within a sun-drenched, typically Australian landscape. It explores themes of lawlessness and authority in the bush.

These major works, along with others, helped forge a visual narrative for the young nation, celebrating its unique character and experiences.

The Big Picture: A Monumental Commission

Roberts' capacity for large-scale, detailed work culminated in The Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia by H.R.H. The Duke of Cornwall and York (later H.M. King George V), May 9, 1901, commonly known as The Big Picture. Commissioned by the Australian Art Association, this enormous painting (measuring over 3 by 5 metres) depicts the historic event held in Melbourne's Royal Exhibition Building.

Roberts undertook the commission with meticulous care, making numerous individual portrait studies of the attendees. The final work contains over 250 recognisable figures, including politicians, dignitaries, and prominent citizens. Completing this monumental task took Roberts nearly three years, much of it spent in London where many of the subjects were available for sittings. While the constraints of the commission perhaps limited artistic freedom, The Big Picture remains a significant historical document and a testament to Roberts' skill and dedication. It is now housed in Parliament House, Canberra.

Landscapes and Light

Beyond the grand narratives, Roberts was a dedicated landscape painter throughout his career. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the specific quality of Australian light and atmosphere. His earlier plein air studies, such as A Winter Morning After Rain, Gardeners Creek (1885) and Allegro con Brio, Bourke St West (c. 1885–86, painted alongside McCubbin), demonstrate his early mastery of capturing fleeting effects and urban scenes.

His landscapes often feature the muted greens, blues, and ochres characteristic of the Australian bush, rendered with a sensitivity to tonal values and atmospheric perspective. He painted various locations across Victoria and New South Wales, always seeking to convey the truth of the scene before him. Works like The Sunny South (c. 1887) exemplify the Heidelberg School's celebration of the Australian climate and landscape.

The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition

In August 1889, Roberts, Streeton, and Conder, with contributions from McCubbin, Charles Douglas Richardson, and others, staged the groundbreaking "9 by 5 Impression Exhibition" at Buxton's Art Gallery in Melbourne. The exhibition took its name from the dimensions of the cigar box lids upon which most of the small oil sketches were painted (approximately 9 inches by 5 inches).

This exhibition was a bold statement, showcasing rapid sketches or "impressions" intended to capture fleeting moments of light and colour. It challenged the prevailing academic emphasis on highly finished works. The artists decorated the gallery with silk scarves and Japanese umbrellas, reflecting the influence of the Aesthetic Movement.

The exhibition provoked considerable controversy. While some viewers were intrigued, the leading conservative critic James Smith famously derided the works as "palpably slapdash" and lacking finish. However, the 9 by 5 Exhibition is now recognised as a landmark event in Australian art history, signalling the arrival of a modern, locally inflected art practice and asserting the value of the sketch as a finished work in its own right.

Portraiture

Tom Roberts was also a highly accomplished portrait painter. Throughout his career, he received numerous commissions and painted portraits of friends, fellow artists, and prominent figures in Australian society. His portraits are noted for their psychological insight and solid draughtsmanship, combined with the fluid brushwork characteristic of his style.

He painted notable figures such as the politician Sir Henry Parkes and fellow artist Louis Abrahams. His portraits often convey a sense of the sitter's character and presence, moving beyond mere likeness. This skill complemented his narrative works, particularly the individual studies undertaken for The Big Picture. His ability to capture character was integral to his broader project of defining Australian identity.

Artistic Circle and Collaborations

Roberts was a gregarious figure and a natural leader, fostering a strong sense of community among the artists of his generation. His friendship and collaboration with Frederick McCubbin were foundational to the Heidelberg School. Their shared studies, painting expeditions, and establishment of the Box Hill camp were crucial early steps.

He also maintained close working relationships with Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder during the key Heidelberg years. Their shared time at Eaglemont produced some of the most celebrated works of Australian Impressionism. Louis Abrahams remained a close friend and supporter.

Roberts' circle extended beyond the core Heidelberg group. He interacted with many other artists of the time, including Walter Withers, Jane Sutherland, and Clara Southern. During his time abroad, he associated with John Peter Russell and was aware of international figures like Whistler and Bastien-Lepage. Later influences included the Italian-born painter Girolamo Nerli, who spent time in Melbourne and Sydney. Roberts also studied alongside artists like E. Phillips Fox and Tudor St. George Tucker in Melbourne before his European trip. This network of friendships and professional associations was vital to the development and dissemination of the Heidelberg School's ideals.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Roberts spent a significant period in England from 1903 to 1919, partly to complete The Big Picture and later working during World War I as an orderly at the 3rd London General Hospital. He returned to Australia in 1919 and eventually settled in Kallista, in the Dandenong Ranges outside Melbourne, where he continued to paint landscapes.

In his later years, his work perhaps did not break new ground in the way his earlier paintings had, but he remained a respected figure. An interesting facet of his diverse talents is revealed in a collaboration with his sister, Emma. Together, they produced a series of detailed botanical watercolours, including one titled Blossoming Plant, which demonstrate a keen eye for scientific observation alongside artistic skill. These works are now held in the Gwillim Collection at McGill University Library in Montreal, Canada. While some accounts mention his sharp, truth-seeking questioning style, specific anecdotes about him exposing deceitful individuals remain elusive in documented records.

Although he received no official honours like a knighthood during his lifetime, Tom Roberts' reputation grew steadily after his death. He is widely regarded as the "Father of Australian Landscape Painting" and a key architect of Australian Impressionism. His major works are icons of Australian culture, held in major national and state galleries.

His influence lies in his pioneering role in adapting Impressionist techniques to the Australian environment, his leadership within the Heidelberg School, his creation of powerful national narrative paintings, and his dedication to capturing the unique character of Australian life and landscape. Tom Roberts helped Australians see their own country in a new light, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's art and identity. His work continues to be celebrated for its technical skill, its historical significance, and its enduring evocation of Australia.