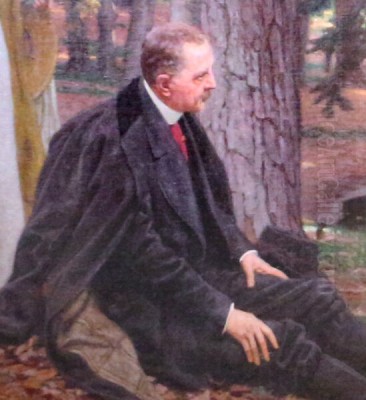

The turn of the twentieth century in Vienna was a period of extraordinary artistic ferment, a time when old conventions were challenged, and new forms of expression blossomed. Central to this cultural upheaval was the Vienna Secession, a movement that sought to break away from the conservative artistic establishment. Among the figures associated with this vibrant era was Friedrich Koenig, an artist whose life and work reflect the ideals and aspirations of this transformative period in art history. Born in 1857 and passing away in 1941, Koenig's career spanned a critical juncture, witnessing the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the dawn of modernism.

It is important at the outset to distinguish this Friedrich Koenig from other notable individuals bearing similar names. He is not to be confused with Friedrich Koenig (1774-1833), the German inventor renowned for developing the high-speed steam-powered printing press. Nor is he Fritz Koenig (1924-2017), the prominent German sculptor famous for works such as "The Sphere," which once stood at the World Trade Center in New York. The Friedrich Koenig under discussion here was an Austrian artist, primarily a painter and graphic artist, deeply embedded in the Viennese art scene of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Education in Imperial Vienna

Friedrich Koenig was born in Vienna, the imperial capital that was then a crucible of artistic and intellectual innovation. His formative years coincided with the Ringstrasse era, a period of grand architectural development and a flourishing of the arts, albeit often within traditional academic confines. To pursue his artistic inclinations, Koenig enrolled in two of Vienna's most significant art institutions.

He first attended the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), an institution founded in 1867 and closely associated with the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry (now the MAK). The Kunstgewerbeschule was progressive for its time, aiming to bridge the gap between fine arts and applied arts, and to elevate the quality of Austrian craftsmanship. Here, students were exposed to a curriculum that emphasized design, ornamentation, and practical application, often under the tutelage of influential figures like the painter Ferdinand Laufberger or the architect Heinrich von Storck. This education would have provided Koenig with a strong foundation in design principles and various artistic techniques.

Following his studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule, Koenig furthered his education at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). The Academy represented the more traditional, established bastion of artistic training in Vienna. It upheld classical ideals and a rigorous academic curriculum focused on drawing from life, historical painting, and mastering established techniques. While the Academy was often seen as conservative by emerging modernists, it provided an indispensable grounding in the fundamentals of art for generations of Austrian artists. Koenig's dual education equipped him with both the innovative spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement and the technical proficiency of academic training.

The Rise of the Vienna Secession

The late 19th century in Vienna was marked by a growing dissatisfaction among younger artists with the prevailing artistic climate, particularly the historicism and conservatism championed by the Association of Austrian Artists (Künstlerhaus). This discontent culminated in 1897 with the formation of the Vienna Secession (Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession). This group, led by iconic figures such as Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and Joseph Maria Olbrich, sought to create a platform for contemporary, international art, free from the constraints of the academic establishment.

The Secessionists aimed for a renewal of the arts, embracing a wide range of styles from Symbolism and Art Nouveau (known as Jugendstil in German-speaking countries) to early forms of Expressionism. They championed the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, where painting, sculpture, architecture, and decorative arts would be integrated. Their motto, "To every age its art, to every art its freedom" (Der Zeit ihre Kunst, Der Kunst ihre Freiheit), was emblazoned above the entrance of their purpose-built exhibition hall, the Secession Building, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich.

Friedrich Koenig was a member of this groundbreaking movement. His involvement signifies his alignment with its progressive ideals and his desire to participate in the creation of a new Austrian art. The Secession provided artists like Koenig with opportunities to exhibit their work outside the traditional salon system and to engage with international artistic trends.

Koenig's Artistic Focus: Painting and Graphic Arts

As an artist, Friedrich Koenig was primarily known as a painter, printmaker, and engraver. Within the context of the Vienna Secession, these media were highly valued. Painting allowed for explorations of symbolism, mood, and decorative stylization, hallmarks of Jugendstil. Artists like Gustav Klimt, Carl Moll, and Max Kurzweil pushed the boundaries of painting, incorporating rich ornamentation and psychological depth.

Koenig's work as a painter would likely have reflected these trends. While specific details of a large body of his painted oeuvre are not as widely documented as those of the Secession's leading figures, his paintings would have engaged with the stylistic currents of the time. This could include landscapes imbued with symbolic meaning, allegorical scenes, or portraits that captured the introspective mood of the fin-de-siècle. The emphasis on decorative line, flattened perspectives, and harmonious color palettes, characteristic of Jugendstil, would have been elements he explored.

Graphic arts held a particularly significant place within the Vienna Secession. The movement's journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), was a masterpiece of Jugendstil design, featuring contributions from many Secessionist artists, including illustrations, vignettes, and typographic designs. Printmaking techniques such as woodcut, lithography, and etching were embraced for their expressive potential and their ability to disseminate art to a wider audience. Friedrich Koenig, as a printmaker and engraver, would have found a fertile ground for his talents within this environment. His graphic works likely contributed to the distinctive visual identity of the Secession and its publications.

Representative Works and Stylistic Tendencies

While a comprehensive catalogue of Friedrich Koenig's works requires deeper archival research, some examples provide insight into his artistic contributions. He is known to have created illustrations for Ver Sacrum, placing him directly within the Secession's most iconic publishing endeavor. His contributions would have adhered to the high artistic standards and distinctive Jugendstil aesthetic of the journal.

Paintings such as "Nixenreigen" (Nymphs' Round Dance) or "Frühling" (Spring) suggest an engagement with mythological and allegorical themes, popular among Symbolist and Jugendstil artists. These subjects allowed for imaginative interpretations and the creation of evocative, dreamlike atmospheres. The depiction of nymphs or personifications of seasons often involved sinuous lines, decorative patterns, and a focus on mood rather than strict naturalism. Such works would align with the Secession's broader interest in exploring the inner world, emotion, and the poetic.

His training as an engraver would have lent itself to detailed and precise work, whether in original prints or in reproductive engravings. The meticulous nature of engraving could be combined with the flowing lines of Jugendstil to create intricate and aesthetically pleasing compositions. The Secession's emphasis on craftsmanship meant that printmakers like Koenig were valued for their technical skill as well as their artistic vision.

Contemporaries and the Viennese Artistic Milieu

Friedrich Koenig operated within a rich and dynamic artistic community. The Vienna Secession itself brought together a diverse group of talents. Beyond the towering figure of Gustav Klimt, its first president, there were many other significant artists whose work and ideas shaped the movement.

Koloman Moser was a polymath, excelling in painting, graphic design, and decorative arts. He was a key figure in the development of the Wiener Werkstätte, an offshoot of the Secession dedicated to high-quality craftsmanship in everyday objects. Josef Hoffmann, an architect and designer, was another co-founder of both the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, known for his geometric clarity and elegant modernism.

Painters like Carl Moll were instrumental in organizing Secession exhibitions and promoting modern art in Vienna. Max Kurzweil, known for his poignant Symbolist paintings, and Alfred Roller, who later became a renowned stage designer for Gustav Mahler at the Vienna State Opera, were also important Secession members. Other notable figures included Josef Maria Auchentaller, Ferdinand Andri, Rudolf Jettmar, Ernst Stöhr, and Wilhelm List, each contributing to the diverse artistic output of the Secession.

The influence of international art movements was also palpable. The Secessionists were keen to exhibit works by foreign artists, bringing French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, Belgian Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff, and Swiss artists such as Ferdinand Hodler to the Viennese public. The English Arts and Crafts movement, with figures like William Morris and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (who exhibited with the Secession), also had a profound impact, particularly on the Secession's emphasis on applied arts and the Gesamtkunstwerk. Koenig would have been exposed to these diverse influences, enriching his artistic perspective.

Later, a younger generation, including Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, would emerge, initially influenced by Klimt and the Secession, but soon forging their own paths towards Austrian Expressionism. While Koenig belonged to the founding generation of the Secession, the artistic landscape around him was constantly evolving.

The Broader Context of Jugendstil

Friedrich Koenig's art is best understood within the international context of Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil as it was known in Austria and Germany. This style, flourishing from the 1890s to the brink of World War I, was a reaction against the academic art of the 19th century and the perceived ugliness of industrialization. It sought inspiration in natural forms, particularly curvilinear lines, flowers, and plants, and aimed to create a new aesthetic for a modern age.

In Vienna, Jugendstil developed its own distinct characteristics. While sharing the organic lines and decorative impulse of French or Belgian Art Nouveau, Viennese Jugendstil, especially in the work of artists like Hoffmann and Moser, often incorporated more geometric elements and a greater sense of order and restraint. This can be seen in the design of the Secession Building itself, with its iconic golden laurel-leaf dome (often nicknamed the "golden cabbage") and its clear, almost classical facade.

Koenig's work as a painter and graphic artist would have participated in this stylistic dialogue. His compositions likely featured the flowing, organic lines typical of Jugendstil, combined with a strong sense of design and pattern. The themes he explored, such as nature, mythology, and the human figure (often stylized and elongated), were common preoccupations for Jugendstil artists across Europe. The emphasis on creating a harmonious and aesthetically pleasing whole, even in utilitarian objects or graphic design, was a core tenet of the movement that Koenig, with his background in the School of Arts and Crafts, would have appreciated.

Printmaking in the Secessionist Era

The role of printmaking and graphic design during the Vienna Secession cannot be overstated, and Friedrich Koenig's specialization in these areas places him at the heart of a crucial aspect of the movement. Ver Sacrum, the official magazine of the Secession, published from 1898 to 1903, stands as a monument to Jugendstil graphic art. It was conceived as a total work of art in itself, with every aspect, from typography and layout to illustrations and decorative borders, carefully considered.

Artists like Koenig who contributed to Ver Sacrum were not merely providing illustrations; they were participating in an ambitious project to redefine the illustrated journal as an art form. The magazine utilized advanced printing techniques and high-quality paper, and it showcased a wide array of graphic styles, from delicate line drawings to bold woodcuts. Koenig's skills as an engraver and printmaker would have been highly valued in this context. His contributions might have included full-page illustrations, decorative vignettes, or even cover designs.

Beyond Ver Sacrum, the Secessionists actively promoted printmaking as an independent art form. They organized exhibitions that included prints alongside paintings and sculptures, helping to elevate the status of graphic arts. Techniques such as color woodcut, pioneered by artists like Carl Moll and Emil Orlik (though Orlik was more associated with Prague and Berlin, his influence was felt), and sophisticated lithography were explored for their expressive possibilities. Koenig's involvement in printmaking aligned perfectly with this Secessionist ethos, which saw graphic art not just as a reproductive medium but as a vital field for original artistic creation.

Later Career and Legacy

The heyday of the Vienna Secession was relatively brief, with its most intense period of activity occurring in the years around the turn of the century. By 1905, a significant split occurred within the movement, with Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Carl Moll, and others leaving to form a new group, the Kunstschau, partly due to disagreements over the Secession's direction and its relationship with applied arts.

Information about Friedrich Koenig's career trajectory after this period and leading up to his death in 1941 is less prominent in general art historical narratives, which tend to focus on the initial, groundbreaking phase of the Secession or the subsequent rise of Austrian Expressionism. However, he remained an artist, and his life extended through the tumultuous interwar period in Austria, the Anschluss, and the beginning of World War II. The artistic landscape changed dramatically during these decades, with new movements and styles emerging.

Koenig's legacy is primarily tied to his participation in the Vienna Secession. As a member of this influential group, he contributed to a pivotal moment in Austrian and European art history. His work, particularly in painting and graphic arts, helped to shape the visual culture of Viennese Jugendstil. While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his Secessionist colleagues like Klimt or Schiele (who represented a later, more expressionistic phase), Koenig played his part in the collective effort to modernize Austrian art and to create a new visual language for a changing world.

His dedication to both fine and graphic arts reflects the Secession's holistic approach to creativity. The artists of this era sought to break down the barriers between different artistic disciplines and to infuse art into all aspects of life. Friedrich Koenig, through his paintings, prints, and engravings, was a participant in this ambitious and ultimately transformative endeavor.

The Importance of Distinguishing Artists

Reiterating the distinction is crucial: the Friedrich Koenig (1857-1941) discussed here is the Viennese painter and graphic artist of the Secession movement. He is a figure distinct from Friedrich Koenig (1774-1833), the inventor whose steam press revolutionized printing and, by extension, the dissemination of information and culture. The inventor Koenig's work had a profound societal impact, but it belongs to the realm of technology and industrial history.

Similarly, the artist Friedrich Koenig should not be confused with the more contemporary German sculptor Fritz Koenig (1924-2017). Fritz Koenig was a major figure in post-World War II sculpture, known for his powerful, often abstract, bronze works that explored themes of vulnerability and resilience. His most famous piece, "Große Kugelkaryatide N.Y." (The Sphere), which survived the 9/11 attacks, has become an enduring symbol. While both were artists, their timelines, national contexts, and artistic styles are entirely different.

Understanding these distinctions is vital for accurate art historical discourse. Friedrich Koenig (1857-1941) holds his own place as an artist who contributed to the vibrant cultural tapestry of Vienna at the turn of the 20th century, a city that was a cradle of modern thought and art.

Conclusion: A Viennese Artist of His Time

Friedrich Koenig (1857-1941) was an artist shaped by and contributing to the unique artistic environment of Vienna during a period of profound change. His education at both the progressive School of Arts and Crafts and the traditional Academy of Fine Arts provided him with a versatile skill set. His membership in the Vienna Secession placed him at the forefront of the movement to modernize Austrian art, to break free from academic constraints, and to embrace new forms of expression.

As a painter and, significantly, as a graphic artist and engraver, Koenig participated in the flourishing of Jugendstil in Vienna. His contributions to publications like Ver Sacrum and his own creative works would have reflected the era's emphasis on decorative line, symbolic content, and the integration of art into broader cultural life. He worked alongside some of the most iconic figures of Austrian art, including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, and was part of a community that sought to redefine the role of the artist and the nature of art itself.

While perhaps overshadowed in popular accounts by some of his more famous contemporaries, Friedrich Koenig represents the many dedicated artists who collectively created the rich artistic fabric of the Vienna Secession. His work is a testament to a time when Vienna was a vibrant center of innovation, and when artists dared to declare, "To every age its art, to every art its freedom." His legacy is woven into the story of this remarkable artistic revolution.