Fritz Mackensen stands as a significant, albeit sometimes complex, figure in the landscape of German art at the turn of the 20th century and beyond. A painter, educator, and a principal founder of the influential Worpswede artists' colony, Mackensen's career spanned periods of immense artistic innovation and profound socio-political upheaval. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of German Realism and Naturalism, also engaged with the burgeoning modern art movements, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural fabric of his time. This exploration delves into his life, his artistic contributions, his pivotal role in Worpswede, his interactions with contemporaries, and the enduring, sometimes controversial, legacy he left behind.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on April 8, 1866, in Greene, near Kreiensen, in what was then the Duchy of Brunswick, Germany, Fritz Mackensen's early life set the stage for a career deeply connected to the German soil and its people. His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training at some of the most respected institutions of the era. He commenced his studies at the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy) in 1884, a bastion of academic tradition, particularly known for its historical and genre painting.

Following his time in Düsseldorf, Mackensen sought further refinement and exposure to different artistic currents by moving to the Kunstakademie München (Munich Art Academy) in 1888. Munich, at this time, was a vibrant artistic hub, more open to newer influences like French Realism and Impressionism than some other German centers. It was here that he likely deepened his appreciation for artists who depicted everyday life and the natural world with unvarnished truthfulness. Figures like Wilhelm Leibl, a leading German Realist who himself had been influenced by Gustave Courbet, were prominent in the Munich art scene and advocated for a direct, unidealized approach to painting.

Mackensen's academic training provided him with a solid foundation in traditional techniques, including drawing, composition, and the use of color. However, like many artists of his generation, he began to feel the constraints of purely academic art. The late 19th century was a period of questioning established norms, with a growing desire among artists to find more authentic and personal modes of expression, often by turning away from urban centers and towards nature and rural life. This sentiment would become a driving force in Mackensen's subsequent career path.

The Genesis of Worpswede

The most defining chapter in Fritz Mackensen's artistic life began in 1889 with his "discovery" of Worpswede, a remote and then little-known village situated in the Teufelsmoor (Devil's Moor), a vast peat bog landscape near Bremen in Lower Saxony. Drawn by the stark, melancholic beauty of the moor, its expansive skies, and the simple, hardworking lives of its inhabitants, Mackensen saw in Worpswede an escape from the artifice of city life and the rigid conventions of the art academies.

He was not alone in this sentiment. In the same year, he, along with his friend and fellow artist Otto Modersohn, whom he had met during his studies, decided to settle in Worpswede. They were soon joined by Hans am Ende, another artist seeking similar inspiration. Together, these three are considered the founding fathers of the Worpswede artists' colony. Their vision was to live and work in close communion with nature, capturing its moods and the lives of the local peasantry with honesty and empathy.

The establishment of Worpswede was part of a broader European trend of artists' colonies, such as Barbizon in France, where artists like Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Camille Corot had sought refuge from urban industrialization and academic constraints to paint directly from nature. Similarly, Pont-Aven in Brittany attracted artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard. The Worpswede artists shared this desire for authenticity and a return to simpler, more "primitive" ways of life, believing that such an environment would foster a more genuine and spiritually resonant art.

The colony quickly gained recognition, especially after a highly successful group exhibition at the Glaspalast in Munich in 1895. This exhibition brought Worpswede to national, and even international, attention, establishing its reputation as a significant center for German landscape and genre painting. The artists' commitment to depicting the unique character of the Teufelsmoor and its people resonated with a public increasingly interested in regional identity and the perceived purity of rural existence.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Fritz Mackensen's artistic style was primarily rooted in Naturalism and Realism, heavily influenced by 19th-century French masters such as Gustave Courbet and the painters of the Barbizon School. He sought to depict the world around him with objective truthfulness, focusing on the tangible reality of his subjects, whether landscapes or human figures. His palette often consisted of earthy tones, reflecting the somber and atmospheric quality of the moorland environment.

A key characteristic of Mackensen's work was his profound empathy for the peasant communities of Worpswede. He portrayed their daily toil, their deep connection to the land, and their quiet dignity without romanticization or sentimentality. His figures are often monumental and imbued with a sense of stoicism, reflecting the harshness of their lives but also their resilience. This focus on the common person and rural labor aligned with the broader social consciousness emerging in art during this period.

While primarily a Realist, Mackensen's work also showed an awareness of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) principles, particularly in some of his compositions and decorative sensibilities. This can be seen in the rhythmic lines and the sometimes stylized representation of natural forms. However, the core of his art remained a commitment to capturing the essential character of his subjects. He was particularly adept at conveying the atmospheric conditions of the Teufelsmoor – the vast, often overcast skies, the play of light on the waterlogged land, and the sense of solitude and timelessness that pervaded the landscape.

His themes often revolved around the cycles of life and nature: work in the fields, family life, religious observance, and the solitary individual within the expansive landscape. There was a strong element of "Heimatkunst" (homeland art) in his work, celebrating local traditions and the perceived virtues of rural German life, which resonated with contemporary nationalist sentiments. However, his best works transcend mere regionalism through their universal human themes and powerful execution.

Key Representative Works

Several paintings by Fritz Mackensen stand out as emblematic of his style and thematic preoccupations, earning him critical acclaim and cementing his reputation.

One of his most celebrated early works is Gottesdienst im Freien (Open-Air Service, or Worship in the Moor), painted in 1895. This large-scale canvas depicts a congregation of Worpswede peasants gathered for a religious service in the open moorland. The figures, dressed in traditional dark clothing, are rendered with a solemn dignity, their faces reflecting a deep piety. The vast, brooding sky and the stark landscape dominate the composition, emphasizing the community's connection to both their faith and their environment. The painting was a sensation when exhibited at the Munich Glaspalast, winning Mackensen a gold medal and bringing widespread recognition to the Worpswede colony. It captured a sense of authentic German spirituality and rural tradition that appealed to the zeitgeist.

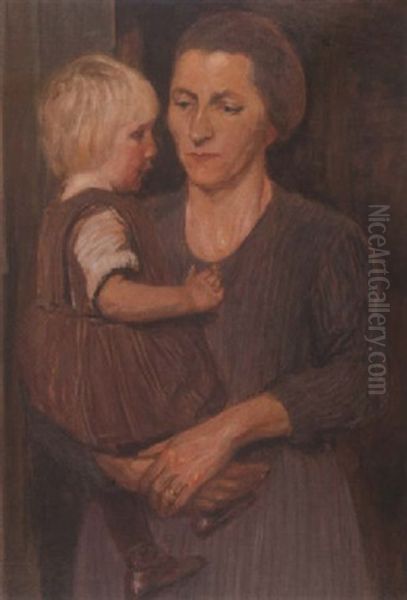

Another significant work is Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child), painted in 1892. This piece showcases Mackensen's ability to convey tender human emotion within a realistic framework. The depiction of the mother and child is unsentimental yet deeply moving, highlighting the universal theme of maternal love. The figures are robust and grounded, typical of Mackensen's portrayal of peasant life.

Einsame Fahrt (Solitary Journey), from 1896, exemplifies his engagement with the landscape and the theme of solitude. The painting often features a lone figure in a small boat navigating the waterways of the Teufelsmoor. The mood is contemplative and melancholic, with the vastness of nature dwarfing the human presence, yet also suggesting a profound, almost spiritual connection between the individual and the environment. The subdued colors and the emphasis on atmosphere are characteristic of his moorland scenes.

These works, among others, demonstrate Mackensen's skill in capturing both the physical reality and the emotional resonance of his subjects. They reflect his deep immersion in the Worpswede environment and his commitment to an art that was both truthful and meaningful.

The Worpswede Community: Collaboration and Conflict

The Worpswede artists' colony grew rapidly after its initial success. Fritz Mackensen, Otto Modersohn, and Hans am Ende were soon joined by other notable artists, each bringing their unique perspectives while sharing a common ethos. Among the most prominent figures who became associated with Worpswede were Fritz Overbeck, a landscape painter; Heinrich Vogeler, whose elegant Art Nouveau style brought a different aesthetic to the group, particularly in his designs and illustrations; and, crucially, Paula Becker, who later married Otto Modersohn and became Paula Modersohn-Becker, one of the most important early Expressionist painters in Germany.

The early years of the colony were marked by a spirit of camaraderie and shared artistic purpose. The artists lived and worked in close proximity, often critiquing each other's work and engaging in lively discussions about art and life. They shared a commitment to plein air painting and a desire to break free from academic constraints. Mackensen, as one of the "founding fathers," played a significant role in shaping the colony's early direction and public image.

However, as the colony grew and individual artistic personalities developed, tensions and differences inevitably arose. In 1897, the "Künstlervereinigung Worpswede" (Worpswede Artists' Association) was formally established, but internal disagreements, personal rivalries, and differing artistic visions led to its dissolution by 1899. Despite this formal breakup, Worpswede continued to attract artists and remained an important artistic center.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, for instance, initially studied with Mackensen. While she respected his technical skill and his emphasis on direct observation, her artistic path diverged significantly. She sought a more radical, expressive style, influenced by artists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, pushing beyond the Naturalism favored by Mackensen and most of the early Worpswede painters. Her powerful, often starkly simplified depictions of peasants and self-portraits marked a significant departure and positioned her as a pioneer of German Modernism.

Carl Vinnen, another artist associated with Worpswede, became known for his conservative stance, particularly his role in the "Protest deutscher Künstler" (Protest of German Artists) in 1911 against the perceived dominance of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in German museums. This highlights the diverse, and sometimes conflicting, artistic ideologies present even within a seemingly unified movement like Worpswede.

Later Career and Academic Roles

Fritz Mackensen's career extended well beyond the initial heyday of Worpswede. His reputation as a leading figure in German art led to academic appointments. He became a professor at the Kunsthochschule Weimar (Weimar Art School) in 1910, an institution that, under Henry van de Velde, was a precursor to the Bauhaus. This appointment indicates his standing within the German art establishment.

His involvement in art education continued, and he later served as the director of the Nordische Kunsthochschule in Bremen (which evolved from the former Staatliche Kunstgewerbeschule, or State School of Applied Arts) from 1933 to 1934, and again, under different circumstances, for a period. His teaching would have brought him into contact with younger generations of artists, though his own artistic style remained largely consistent with his earlier Realist and Naturalist principles.

During World War I, Mackensen, like many artists of his generation, was involved in the war effort, possibly producing patriotic works or serving in a capacity related to his artistic skills. The war profoundly impacted the European cultural landscape, and the optimistic spirit of the pre-war era gave way to more somber and critical artistic expressions, such as German Expressionism, exemplified by artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde (who also had a complex relationship with the Nazi regime later), and Max Beckmann. While Mackensen's art did not embrace the radical formal innovations of Expressionism, the gravity of the times may have subtly influenced the mood of his later works.

His continued dedication to depicting rural life and traditional German themes found favor in certain conservative circles, particularly as Germany navigated the turbulent interwar period of the Weimar Republic. This period saw a rise in various artistic movements, from the socially critical New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) of artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz to the abstract experiments of the Bauhaus, led by Walter Gropius. Mackensen's art represented a more traditional, Heimat-focused counterpoint to these avant-garde developments.

The Nazi Era: Complicity and Contradictions

The rise of the National Socialist (Nazi) regime in 1933 brought profound and often devastating changes to the German art world. The Nazis promoted a specific vision of "German art," favoring realistic, heroic, and idyllic depictions of Aryan figures, rural life, and nationalistic themes, while denouncing modern art movements like Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, and Dadaism as "degenerate" (entartete Kunst).

Fritz Mackensen's artistic style, with its emphasis on German landscapes, peasant life, and traditional values, aligned to some extent with the cultural aesthetics favored by the Nazi regime. He joined the NSDAP (Nazi Party) in 1937. During this period, he held positions of influence, including his directorship at the Nordische Kunsthochschule. He participated in the "Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen" (Great German Art Exhibitions) held annually in Munich, which were designed to showcase art approved by the regime. Artists like Arno Breker and Josef Thorak (sculptors) and painters like Adolf Ziegler and Paul Mathias Padua were heavily promoted by the Nazis.

Mackensen's involvement with the Nazi regime is a complex and controversial aspect of his biography. While his art was not overtly propagandistic in the same way as some officially sanctioned Nazi artists, his participation in state-sponsored exhibitions and his party membership indicate a degree of complicity or at least accommodation with the regime. Some sources suggest that while he outwardly conformed, he may have harbored private reservations or even engaged in minor acts of dissent, such as reportedly opposing the persecution of Catholics. However, his public actions placed him within the orbit of Nazi cultural politics.

It is important to contextualize the pressures and choices faced by artists during this dark period. Some artists emigrated, some went into "internal exile," while others, like Mackensen, found ways to continue working within the system. His case highlights the difficult moral and ethical dilemmas faced by individuals under totalitarian rule. The extent of his ideological commitment versus pragmatic careerism remains a subject of historical interpretation.

Post-War Period and Legacy

After the collapse of the Nazi regime in 1945, Germany underwent a period of de-Nazification. Fritz Mackensen, despite his party membership and participation in Nazi-era exhibitions, appears to have navigated this process relatively successfully, allowing him to continue his artistic career. He passed away in Bremen on May 12, 1953, at the age of 87.

Fritz Mackensen's legacy is multifaceted. He is undeniably a key figure in the history of the Worpswede artists' colony, which remains an important site in German art history, attracting visitors and artists to this day. His early paintings, particularly Gottesdienst im Freien, are considered masterpieces of German Naturalism and played a crucial role in establishing Worpswede's reputation. His depictions of the Teufelsmoor and its people have a lasting power and authenticity.

He influenced a generation of artists, not only through his direct teaching but also through the example he set with the founding of Worpswede. Artists like Paula Modersohn-Becker, despite ultimately pursuing a very different artistic path, received early guidance from him. His commitment to depicting the local environment and its inhabitants contributed to a broader appreciation for regional German art.

However, his activities during the Nazi era cast a shadow over his later career and complicate his overall assessment. Art historians continue to grapple with how to evaluate artists who collaborated or were associated with the Nazi regime. This aspect of his life necessitates a critical examination alongside his artistic achievements.

In conclusion, Fritz Mackensen was an artist of considerable talent and influence. His contribution to the founding and development of the Worpswede colony was pivotal, and his paintings of the North German landscape and its people hold an important place in the canon of German Realism. While his later career was intertwined with the problematic cultural politics of the Third Reich, his earlier achievements ensure his continued significance in the study of German art at the turn of the 20th century. His life and work offer a compelling case study of an artist navigating periods of profound artistic change and challenging historical circumstances. The enduring appeal of Worpswede itself is, in no small part, a testament to the vision he helped to realize.