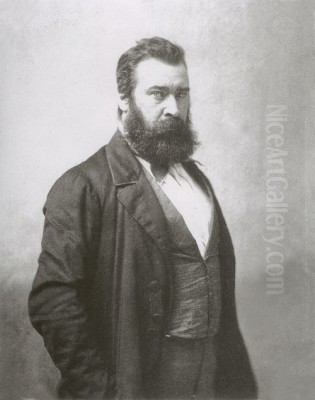

Jean-François Millet stands as a pivotal figure in nineteenth-century French art, renowned primarily for his profound and dignified portrayals of peasant life. Bridging the gap between the waning influence of Romanticism and the burgeoning force of Realism, Millet carved a unique niche for himself, becoming a leading member of the Barbizon School. His work, often imbued with a quiet solemnity and a deep empathy for the rural working class, captured the rhythms of agricultural existence with unprecedented honesty and monumentality. Though often controversial in his time, his art left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists and continues to resonate with its timeless depiction of human labor and connection to the land. His life spanned from October 4, 1814, to January 20, 1875, a period of significant social and artistic transformation in France.

Humble Beginnings and Artistic Awakening

Jean-François Millet was born into a peasant family in the small village of Gruchy, Gréville-Hague, in Normandy. This rural background profoundly shaped his worldview and artistic sensibilities. Unlike many artists who came from urban or bourgeois settings, Millet experienced firsthand the toil and simplicity of agricultural life. His family, recognizing his innate talent for drawing, supported his artistic inclinations. His grandmother, in particular, played a significant role in his upbringing, instilling in him a strong sense of piety and respect for the natural world and the dignity of labor, themes that would permeate his later work.

At the age of nineteen, Millet's talent was evident enough that he was sent to the nearby port town of Cherbourg to pursue formal art training. There, he studied under two local painters, Bon Du Mouchel and Lucien-Théophile Langlois. Langlois, himself a former pupil of the notable Neoclassical painter Baron Gros, recognized Millet's potential and, along with the municipality of Cherbourg, helped secure a stipend for the young artist to continue his studies in Paris. This move marked a significant step, transitioning Millet from his provincial roots to the epicenter of the French art world.

Parisian Studies and Early Career

In 1837, Millet arrived in Paris and enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. He entered the studio of Paul Delaroche, a highly successful academic painter known for his historical scenes. The environment of the École and Delaroche's studio, however, proved somewhat stifling for Millet. He found the emphasis on academic convention and historical subjects less compelling than his own developing interests. While in Paris, he spent considerable time studying the Old Masters at the Louvre, finding particular inspiration in the works of Michelangelo, whose powerful figures resonated with Millet's own inclination towards monumental forms, and Nicolas Poussin, whose classical compositions and pastoral themes offered a different kind of model.

Millet's initial years in Paris were marked by struggle. His official debut at the Paris Salon in 1840 went largely unnoticed. To support himself, he undertook various commissions, painting portraits, small mythological scenes, and even shop signs. His early works often reflected the prevailing tastes, sometimes adopting a lighter, more Rococo-influenced style, quite different from the somber gravity of his later, more famous paintings. During this period, he married Pauline-Virginie Ono in 1841, but tragedy struck when she died from tuberculosis just three years later in 1844. This personal loss, combined with financial hardship and artistic uncertainty, contributed to a period of difficulty for the artist.

The Move to Barbizon and the Barbizon School

The late 1840s were a turning point for Millet, both personally and artistically. He entered into a relationship with Catherine Lemaire, who came to Paris to work as his housekeeper and would eventually become his second wife (they married in a civil ceremony in 1853 and religiously just before his death in 1875) and the mother of his nine children. Facing continued financial instability and seeking refuge from a cholera epidemic sweeping Paris, Millet made a decisive move in 1849. Along with his family and fellow artist Charles Jacque, he relocated to the village of Barbizon, situated on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau.

This move proved crucial for his artistic development. Barbizon had already become a gathering place for artists seeking to escape the confines of the city and the academy, drawn by the desire to paint landscapes directly from nature. Millet quickly became a central figure in what would become known as the Barbizon School. This informal group included painters like Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, Constant Troyon, and Jules Dupré. While primarily landscape painters, the Barbizon artists shared a commitment to direct observation and a rejection of idealized, academic formulas, paving the way for later movements like Impressionism.

Millet, however, distinguished himself within the group. While he painted pure landscapes, his primary focus shifted definitively towards the human figure within the rural environment. He spent the next twenty-six years, essentially the rest of his life, in Barbizon, immersing himself in the daily lives of the local peasants and transforming their humble existence into subjects of profound artistic significance. His friendship with Théodore Rousseau was particularly important, providing mutual support and artistic camaraderie until Rousseau's death in 1867.

Mature Style: Dignity, Labor, and Realism

Settling in Barbizon allowed Millet to fully develop his signature style and thematic concerns. He turned away almost completely from mythological or purely pastoral subjects, focusing instead on the farmers, shepherds, and laborers he saw around him. His approach was rooted in Realism – the movement championed by contemporaries like Gustave Courbet – which sought to depict ordinary life and contemporary subjects with truthfulness and objectivity, rejecting the idealized conventions of Academic art.

Millet's realism, however, possessed a unique quality. He imbued his peasant figures with a sense of monumentality and timeless dignity, often silhouetted against the sky or landscape, giving them an almost sculptural weight. His compositions were carefully structured, often simple yet powerful, emphasizing the essential gestures of labor. His color palette became more somber and earthy, dominated by browns, grays, and muted greens, reflecting the tones of the soil and the hardships of rural life. He masterfully used light, often depicting figures at dawn or dusk, enhancing the poetic and sometimes melancholic mood of his scenes.

While committed to depicting reality, Millet's work often carried deeper connotations. Critics and admirers alike debated the extent to which his paintings were purely objective observations or contained elements of social commentary, religious sentiment, or even a form of rustic romanticism. He depicted the harshness of peasant labor but also its inherent nobility and connection to the cycles of nature. His figures, though specific individuals observed in Barbizon, often took on the quality of archetypes, representing the enduring human condition tied to the land.

Iconic Works: Sowing, Gleaning, Praying

Millet produced his most celebrated works during his time in Barbizon. These paintings cemented his reputation and became icons of nineteenth-century art.

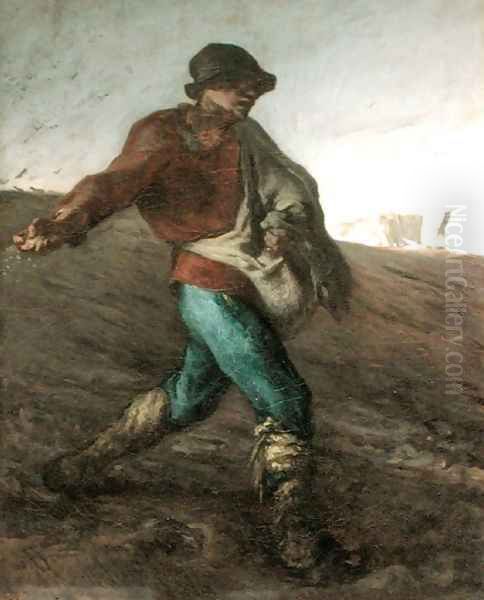

The Sower (1850): Exhibited at the Salon of 1850, The Sower depicts a lone peasant striding across a darkening field, scattering seed with a powerful, rhythmic gesture. The figure is monumental, almost heroic, silhouetted against a dramatic sky. The painting caused a stir at the Salon; some critics saw it as a raw, even brutal depiction of labor, while others perceived a socialist undertone, viewing the sower as a symbol of the potentially rebellious working class, especially in the wake of the 1848 revolutions. For Millet, it represented the timeless, essential act of planting, fundamental to human survival. Its energy and bold composition influenced many later artists, including Vincent van Gogh.

The Gleaners (1857): Perhaps Millet's most famous work, The Gleaners shows three peasant women stooped over a harvested wheat field, collecting the leftover stalks – a practice legally permitted but reserved for the poorest. In the background, the bounty of the main harvest unfolds under the watchful eye of an overseer on horseback, highlighting the stark contrast between poverty and plenty. Exhibited at the Salon of 1857, the painting provoked intense controversy. Conservative critics condemned its perceived ugliness and its focus on rural poverty, fearing it glorified the lower classes and carried socialist implications. Others praised its honesty and profound empathy. Millet presented the back-breaking labor with unvarnished realism yet imbued the figures with a quiet dignity and classical sense of form, elevating their humble task to a subject worthy of serious art. It remains a powerful statement on social class and labor, now housed in the Musée d'Orsay.

The Angelus (1857-1859): This work depicts a peasant couple pausing their work in a potato field at dusk to pray the Angelus, signaled by the distant church bell tower. Bathed in the warm, fading light, the scene evokes a sense of quiet piety and harmony with nature. Unlike the more controversial Gleaners, The Angelus became immensely popular, widely reproduced and celebrated for its perceived sentimentality and evocation of traditional values. However, its interpretation is complex; some see genuine religious devotion, others a nostalgic longing for a simpler past, while Salvador Dalí famously offered a psychoanalytic interpretation suggesting hidden themes of death and repressed sexuality. The painting's immense fame later in the century led to extraordinary bidding wars when it came up for sale.

Beyond these seminal works, Millet created numerous other powerful images of rural life, including Man with a Hoe (which also caused controversy for its depiction of brutalized labor), Potato Planters, Shepherdess Seated on a Rock, and numerous drawings and pastels that captured the landscape and people of Barbizon with sensitivity and skill.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Millet occupied a significant position within the artistic landscape of his time, interacting with and influencing several key figures.

His relationship with Gustave Courbet, the leading proponent of Realism, was one of mutual respect mixed with distinct differences. Both artists challenged academic norms and focused on contemporary subjects, particularly the lives of ordinary people. Courbet's provocative A Burial at Ornans (1849-50) certainly impacted the art world Millet inhabited. However, Courbet was more overtly political and confrontational in his realism, often depicting subjects with a deliberate lack of idealization that bordered on provocative. Millet, while equally committed to depicting the reality of peasant life, often infused his subjects with a greater sense of solemnity and timelessness, sometimes interpreted as less radical than Courbet's approach.

Honoré Daumier, another major figure associated with Realism, shared Millet's interest in depicting the lives of the working class. Daumier, however, was primarily known for his sharp satirical lithographs commenting on Parisian politics and society, and his painted work often focused on urban themes like lawyers, theater-goers, and third-class railway carriages. While both artists offered social commentary through their art, Daumier's style was often more caricatural and overtly critical, contrasting with Millet's more somber and empathetic portrayal of rural existence.

Within the Barbizon School, Millet's closest associate was Théodore Rousseau. Rousseau was primarily a landscape painter, celebrated for his detailed and atmospheric depictions of the Forest of Fontainebleau. Their friendship was deep and sustained, offering crucial support, particularly during periods when Millet's work faced harsh criticism or failed to sell. They shared a profound love for nature and a commitment to direct observation, even though their primary subjects differed. Millet was deeply affected by Rousseau's death in 1867.

Millet also interacted with other Barbizon painters like Charles-François Daubigny, known for his river landscapes often painted from his studio boat, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, who painted dramatic forest scenes and mythological figures. While part of the same general movement, each artist maintained a distinct style and focus.

Later Life, Recognition, and Death

Although Millet struggled financially for much of his career and faced considerable criticism, his reputation gradually grew, particularly in the 1860s. His works began to attract appreciative patrons, both in France and increasingly in America. He received official recognition when he was awarded the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1868. He continued to work diligently in Barbizon, producing paintings, drawings, and pastels, including a series of evocative landscapes in his later years that showed an increasing interest in light and atmosphere, perhaps reflecting the emerging concerns of the Impressionists.

Despite growing fame, Millet's life remained relatively simple, centered around his large family and his work in Barbizon. He suffered from ill health in his later years, including severe headaches and fainting spells. Jean-François Millet died in Barbizon on January 20, 1875, at the age of sixty. He was buried in the nearby cemetery of Chailly-en-Bière, alongside his dear friend Théodore Rousseau, a fitting resting place for an artist so deeply connected to the Barbizon landscape and community.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Jean-François Millet's impact on the course of modern art was profound and multifaceted. While sometimes overshadowed during his life by the more flamboyant Courbet or the later Impressionists, his work proved deeply influential.

He was a cornerstone of the Realist movement, demonstrating that the lives of ordinary peasants were valid and powerful subjects for art, challenging the hierarchy of genres promoted by the Academy. His commitment to depicting labor with dignity resonated with artists concerned with social issues.

He was a key figure in the Barbizon School, which fundamentally shifted landscape painting towards direct observation and paved the way for Impressionism. Although not an Impressionist himself, his interest in capturing specific light conditions (like dusk in The Angelus) and his focus on everyday rural scenes provided inspiration. Artists like Camille Pissarro, who frequently painted rural landscapes and laborers, and even early Claude Monet show affinities with Barbizon principles.

Perhaps his most significant influence was on Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh deeply admired Millet, seeing him as a "father figure" and the quintessential painter of peasant life. He copied Millet's works extensively, including The Sower, and frequently referenced Millet's empathetic approach in his letters. Van Gogh sought to emulate Millet's ability to convey deep emotion and spiritual significance through the depiction of humble subjects.

Millet's influence extended to Georges Seurat, whose monumental figures in works like Bathers at Asnières echo the sculptural quality and compositional gravity of Millet's peasants. Post-Impressionists and Symbolists also found inspiration in the poetic and sometimes mystical undertones of his work.

Across the Atlantic, American artists like Winslow Homer and Eastman Johnson, who depicted scenes of American rural life and labor, likely looked to Millet's example. His work found eager collectors in America, contributing to his international reputation. Even Salvador Dalí's surrealist obsession with The Angelus testifies to the enduring psychological power of Millet's imagery.

Conclusion: The Painter of the Soil

Jean-François Millet remains a towering figure in nineteenth-century art. Emerging from the very soil he so often depicted, he brought an unparalleled authenticity and empathy to his portrayal of peasant life. As a central member of the Barbizon School and a key proponent of Realism, he challenged artistic conventions and broadened the scope of acceptable subject matter. His iconic works, such as The Sower, The Gleaners, and The Angelus, transcend mere documentation; they are profound meditations on labor, nature, social class, and the human condition. Though sometimes criticized for sentimentality or perceived political messages, his enduring legacy lies in his ability to imbue the humblest of subjects with monumental dignity and timeless resonance. His influence on artists ranging from Van Gogh to Seurat underscores his pivotal role in the transition towards modern art, securing his place as one of history's most important chroniclers of rural life.