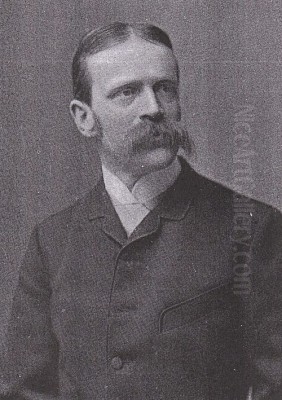

Fritz von Uhde stands as a pivotal figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century, a painter who masterfully navigated the currents of Realism and the burgeoning Impressionist movement. His unique synthesis of these styles, particularly in his depictions of religious themes within contemporary settings, carved out a distinct niche for him in art history. Born Carl Heinrich Hermann Friedrich von Uhde, his journey from a military officer to a leading artist of his time is a testament to his unwavering dedication to his vision, often challenging the artistic and social conventions of his era.

Early Life and Military Interlude

Fritz von Uhde was born on May 22, 1848, in Wolkenburg, Saxony, into a family with artistic inclinations. His father, Hans Hermann von Uhde, was a district court president and a part-time painter, while his maternal grandfather, Friedrich Gotthelf Keller, served as the director of the Royal Museum in Dresden. This familial environment likely sowed the early seeds of artistic interest in young Fritz. In 1866, his formal artistic education began when he was admitted to the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts.

However, Uhde found the academic atmosphere stifling and at odds with his burgeoning artistic spirit. The rigid curriculum and traditional teaching methods did not resonate with him, leading him to leave the Academy in 1867. Following this departure, he embarked on a different path, joining the Saxon cavalry regiment. His military career was respectable; he served diligently, becoming a riding instructor and eventually being promoted to lieutenant in the Imperial German Army. He even saw active service during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. Despite his commitment to military life, the call of art remained strong.

The Transition to a Full-Time Artist

The year 1877 marked a significant turning point in Uhde's life. He made the decisive choice to leave his military career and dedicate himself entirely to painting. This was a bold move, exchanging the security of a military position for the uncertainties of an artist's life. His first destination was Munich, a vibrant artistic hub in Germany at the time. In Munich, he sought to refine his skills, initially looking to the traditions of the Dutch Old Masters. He studied the works of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals, whose mastery of light and characterization deeply impressed him.

His quest for artistic development soon led him to Paris in 1879. The French capital was the epicenter of artistic innovation, and Uhde immersed himself in its dynamic environment. He enrolled in the studio of the Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy. Munkácsy was renowned for his dramatic, often dark-toned genre scenes and historical paintings, executed with a rich, painterly technique. Under Munkácsy's tutelage, Uhde honed his skills in colorism and dramatic composition. A notable work from this period, The Singer (Die Sängerin), was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1880 and received favorable attention, signaling his arrival on the international art scene.

Embracing Impressionism and the "Plein Air" Approach

While Munkácsy's influence was significant, particularly in Uhde's early professional works which often featured a darker palette, a trip to Holland in 1882 proved to be transformative. Encountering the works of Dutch contemporary painters and revisiting the Old Masters in their native context, Uhde began to re-evaluate his approach to light and color. He was particularly drawn to the Hague School painters like Jozef Israëls and Anton Mauve, who combined realistic depictions of everyday life with an atmospheric sensitivity.

This experience, coupled with his exposure to the burgeoning Impressionist movement in Paris, led Uhde to gradually abandon the dark, bituminous palette favored by Munkácsy. He started to experiment with brighter colors and a more broken brushwork, characteristic of Impressionism. He became a proponent of plein air (open-air) painting, a practice central to Impressionism, where artists paint outdoors to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere directly.

Upon his return to Munich, Uhde became closely associated with Max Liebermann, another leading figure in German Impressionism. Liebermann, who had also spent time in Paris and Holland, shared Uhde's enthusiasm for French Impressionist techniques and a commitment to depicting contemporary life. Together with artists like Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt, Uhde and Liebermann would come to be regarded as the "Big Four" of German Impressionism, each contributing to the movement's distinct character in Germany, which often retained a stronger narrative and psychological element compared to its French counterpart. Artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir in France were more focused on the optical sensations of light, while German Impressionists often imbued their scenes with a deeper emotional or social commentary.

Genre Scenes and the Dignity of Ordinary Life

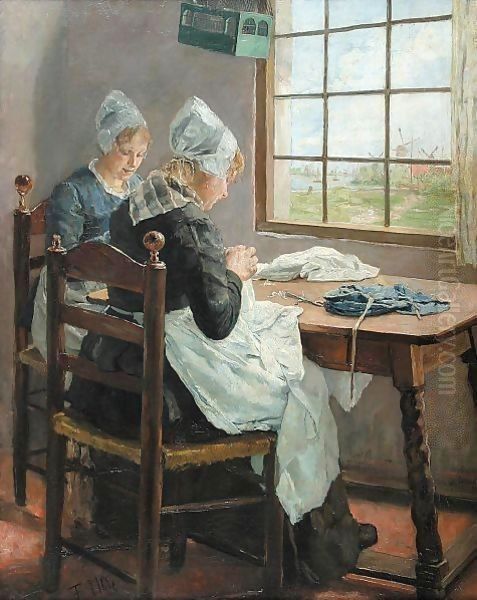

A significant portion of Uhde's oeuvre is dedicated to genre scenes, capturing moments from the everyday lives of ordinary people, particularly peasants, artisans, and children. His military background, which brought him into contact with diverse segments of society, may have informed his empathetic portrayal of these subjects. Works like The Nursery (Kinderstube) and Sisters in the Sewing Room showcase his ability to convey domestic intimacy and quiet industry with sensitivity.

Uhde's depictions of children are particularly noteworthy. He painted them with a remarkable naturalism, avoiding sentimentality while capturing their innocence and unselfconscious absorption in their activities. This aspect of his work drew praise from none other than Vincent van Gogh, who, in a letter to his friend Anthon van Rappard, referred to Uhde as an "excellent child painter," admiring the "strict naturalism" of his portrayals. This contrasted with the more idealized or romanticized depictions of children common in academic art of the period.

His interest in the rural poor and working classes aligned him with the broader Realist tradition exemplified by French artists like Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet, who sought to ennoble the lives of peasants and laborers. However, Uhde's approach was filtered through an Impressionist sensibility, particularly in his handling of light and color, creating a unique blend that was both modern and deeply human.

Religious Iconography Reimagined

Perhaps Fritz von Uhde's most distinctive and controversial contribution to art was his radical reinterpretation of religious subjects. Beginning in the mid-1880s, he started painting scenes from the life of Christ, but with a startling innovation: he depicted biblical figures in contemporary German settings, dressed in the attire of 19th-century peasants and townspeople. This approach aimed to make the Christian narrative more immediate and relatable to his audience, stripping away centuries of idealized, often Italianate, iconographic tradition.

One of his most famous works in this vein is Komm, HErr, sei unser Gast (Come, Lord Jesus, Be Our Guest), painted in 1885. The painting shows Christ, depicted as a humble traveler, entering the simple cottage of a German peasant family who are about to share a meal. The scene is rendered with a quiet dignity, emphasizing Christ's humility and his presence among the poor and ordinary. Another significant work, Lasset die Kindlein zu mir kommen (Suffer Little Children to Come unto Me), portrays Jesus surrounded by contemporary German children in a village schoolroom or a simple interior, his gentle demeanor inviting their trust.

These works were revolutionary for their time. By placing sacred figures in mundane, recognizable environments, Uhde sought to bridge the gap between the historical past of the Gospels and the present reality of his viewers. He aimed to show that the spiritual message of Christianity was timeless and relevant to the lives of ordinary people. This was a departure from the grand, often remote, religious paintings favored by the academies, such as those by historical painters like Peter von Cornelius or Wilhelm von Kaulbach from an earlier generation in Germany.

However, this modernization of sacred art was not without its critics. Some conservative elements, particularly within the Catholic Church and traditional art circles, found his approach to be disrespectful, even "vulgar" or "blasphemous." They objected to the portrayal of Christ and the Holy Family in such humble, contemporary guise, feeling it diminished their sanctity. Despite the controversy, or perhaps partly because of it, these paintings resonated powerfully with many, including progressive theologians and a public eager for a more personal and accessible form of religious expression. His work in this area can be seen as part of a broader European trend of re-evaluating religious art, with artists like the French Léon Lhermitte also depicting biblical scenes in contemporary rural settings.

Schwerer Gang (The Difficult Journey, also known as The Road to Bethlehem), depicting Joseph and a heavily pregnant Mary trudging through a snowy, bleak contemporary landscape, is another poignant example. The hardship and vulnerability of the Holy Family are palpable, rendered with an empathetic realism that underscores the human dimension of the Nativity story. This painting, like others, emphasized a social gospel, highlighting the plight of the poor and suggesting Christ's solidarity with the marginalized.

The Munich Secession and Academic Influence

Fritz von Uhde was not just an individual innovator; he was also an active participant in the artistic movements of his time. In 1892, he became one of the founding members of the Munich Secession, alongside other progressive artists like Max Liebermann, Franz von Stuck, and Wilhelm Trübner. The Secession movements (similar groups also formed in Berlin and Vienna) represented a break from the conservative, state-sponsored art academies and their juried exhibitions. They sought to promote more modern and diverse artistic expressions, including Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau.

Uhde's involvement in the Munich Secession underscored his commitment to artistic freedom and innovation. He served as a respected leader within this group, and his work was frequently exhibited in their influential shows. His reputation grew, and he became an honorary member of the academies in Munich, Dresden, and Berlin, institutions he had once found restrictive.

Later in his career, Uhde also took on an academic role, becoming a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1894. This position allowed him to influence a new generation of artists, passing on his insights into color, light, and the importance of direct observation. His teaching would have emphasized the principles he had developed throughout his career, blending Realist integrity with Impressionist techniques. He was also instrumental, along with Ludwig Dill and Arthur Langhammer, in establishing an art school in Dachau, which became the nucleus of the Dachau art colony, a significant center for landscape and plein air painting in southern Germany.

Style, Technique, and Critical Reception

Uhde's artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of Realist subject matter and Impressionist technique. He typically employed a relatively subdued but luminous palette, often favoring cool blues, grays, and earthy tones, punctuated by warmer highlights. His brushwork, while not as broken or "optical" as that of French Impressionists like Camille Pissarro, was nevertheless visible and expressive, contributing to the texture and vibrancy of his surfaces. He had a remarkable ability to capture the quality of light, whether it was the diffused light of an interior, the crisp light of a winter day, or the dappled sunlight of a summer scene.

His compositions were carefully constructed, often with a focus on human figures and their psychological states. Even in his genre scenes, there is often an underlying narrative or emotional resonance. His religious paintings, in particular, are imbued with a sense of quiet spirituality and profound empathy.

The critical reception of Uhde's work was mixed during his lifetime, especially concerning his religious paintings. While progressive critics and a segment of the public lauded his innovative approach and the sincerity of his vision, conservative factions were often scandalized. Accusations of "ugliness" or "profanity" were leveled against his depictions of Christ among the common people. However, his skill as a painter was widely recognized, and he received numerous awards and honors, including a gold medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900. Artists like Käthe Kollwitz, known for her powerful social realist works, would later build upon the empathetic depiction of the working class that Uhde helped pioneer in German art.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, Fritz von Uhde continued to paint prolifically, though his style did not undergo further radical transformations. He remained committed to his vision of an art that was both modern in its technique and deeply connected to human experience and spiritual values. He passed away in Munich on February 25, 1911, at the age of 62.

Fritz von Uhde's legacy is significant. He played a crucial role in introducing and popularizing Impressionism in Germany, adapting its techniques to a German sensibility that often valued narrative and emotional depth. His willingness to tackle religious themes in a contemporary, humanized manner was groundbreaking and paved the way for other artists to explore sacred subjects in new and personal ways. He demonstrated that modern art could engage with profound spiritual questions without resorting to outdated academic conventions.

His influence extended to many younger artists, not only through his teaching but also through the example of his work. He helped to shift the focus of German art towards contemporary life and the experiences of ordinary people. His paintings are found in major museums across Germany and internationally, and he is recognized as one of the most important German artists of his generation. His ability to infuse everyday scenes with a sense of dignity and his courageous re-envisioning of religious art secure his place as a unique and influential figure who bridged the traditions of the 19th century with the emerging modernism of the 20th. His work continues to be admired for its technical skill, its emotional honesty, and its gentle, pervasive humanism.