Gainsborough Dupont, an artist whose name is inextricably linked with one of British art's most luminous figures, his uncle Thomas Gainsborough, carved out his own distinct, albeit often overshadowed, niche in the vibrant art world of late eighteenth-century England. Born in Sudbury, Suffolk, on December 20, 1754, and christened on January 21, 1755, he was the son of Philip Dupont, a carpenter, and Sarah, Thomas Gainsborough's sister. His life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the workings of a prominent artist's studio, the complexities of artistic influence and inheritance, and the challenges of establishing an independent reputation while working in the brilliant orbit of a celebrated master.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

The artistic environment of the Gainsborough family undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping young Dupont's inclinations. Thomas Gainsborough himself, born in Sudbury, had already established a significant reputation by the time his nephew was growing up. The elder Gainsborough had moved from Suffolk to the fashionable spa town of Bath in 1759, a period during which his portrait practice flourished, attracting a wealthy and influential clientele. It is documented that young Gainsborough Dupont was sent to Bath as a child, where he was raised by his aunt, Mary Gibbion (née Gainsborough), who ran a millinery shop. This proximity to his uncle's burgeoning success and the artistic discussions that must have permeated the family circle likely ignited his passion for art.

By 1772, at the age of seventeen, Gainsborough Dupont was formally apprenticed to his uncle Thomas. This was a significant step, as Thomas Gainsborough was notoriously reluctant to take on pupils. Dupont, in fact, holds the distinction of being his uncle's only formal apprentice. This unique position provided him with unparalleled access to Gainsborough's techniques, studio practices, and artistic philosophy. He would have learned firsthand the secrets behind Gainsborough's famously fluid brushwork, his delicate rendering of fabrics, his sensitive portrayal of character, and his innovative approach to landscape.

In 1775, further formalizing his artistic education, Dupont enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. Thomas Gainsborough had moved his practice to London in 1774, settling at Schomberg House, Pall Mall, and his nephew naturally followed. The Royal Academy, founded in 1768 with Sir Joshua Reynolds as its first president, was the epicenter of the British art world, providing training, exhibition opportunities, and a forum for artistic debate. Dupont's studentship there would have exposed him to a broader range of artistic theories and practices, and to the work of other leading contemporary artists.

The Artist's Hand: Style and Technique

Gainsborough Dupont's artistic output primarily consisted of portraits, with a smaller but notable body of landscape paintings. His style, particularly in portraiture, bears the unmistakable imprint of his uncle. This is hardly surprising, given his immersive apprenticeship. Dupont mastered the light, feathery brushstrokes, the delicate coloration, and the elegant, often slightly melancholic, sensibility that characterized Thomas Gainsborough's mature work. Indeed, the similarity was so pronounced that, then and now, attributions have sometimes been challenging, with certain works by Dupont occasionally mistaken for those of his more famous uncle, or vice versa.

His portraits often display a remarkable sensitivity to the sitter's character, capturing not just a likeness but a sense of personality. He was adept at rendering the textures of fabrics – the shimmer of silk, the softness of velvet, the intricate details of lace – a skill highly valued in an era when costume played a significant role in conveying status and fashion. Works such as his "Portrait of Mary Anne Jolliffe" exemplify his skill in capturing both the sitter's likeness and the fashionable attire of the period with a grace that echoes his uncle's touch.

In his handling of paint, Dupont often employed what was described as a "rapid and harmonious" brushstroke. This suggests a confidence and fluency derived from his training. He also demonstrated an innovative approach to color, sometimes using hues typically reserved for backgrounds, such as browns, whites, and pinks, in the primary depiction of his subjects, lending a poetic and sometimes ethereal quality to his portraits. This subtle manipulation of color and light contributed to the overall atmospheric effect of his work.

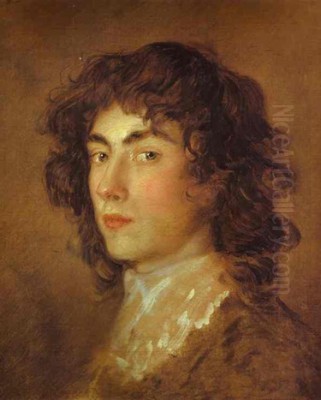

The influence of earlier masters, filtered through Thomas Gainsborough's own artistic admirations, is also discernible. Anthony van Dyck, the Flemish Baroque artist who revolutionized British portraiture in the 17th century, was a profound influence on Thomas Gainsborough, and this reverence was passed on to Dupont. The elegance, elongated figures, and sophisticated portrayal of aristocracy seen in Van Dyck's work found echoes in the Gainsborough studio. Dupont's own "Portrait of the Artist's Nephew" (likely a self-portrait or a portrait of him by his uncle, the title can be ambiguous depending on context and attribution) often shows the sitter in attire reminiscent of Van Dyck's era, a common practice in "Van Dyck dress" portraits.

Beyond Portraiture: Landscapes and Other Works

While portraiture formed the mainstay of his professional practice, Gainsborough Dupont also ventured into landscape painting. Here, his inspiration seems to have diverged somewhat from his uncle's more naturalistic and romantic English landscapes. Dupont is noted for creating landscapes in the manner of Nicolas Poussin, the 17th-century French classical painter. Poussin's landscapes were characterized by idealized scenery, mythological or biblical figures, and a carefully structured, harmonious composition. Dupont's engagement with Poussin's style suggests a desire to explore different artistic traditions and perhaps to demonstrate a versatility beyond the Gainsborough family idiom. One such example is "Woodland Cottage with Cows near a Pond," which, while perhaps less overtly Poussinesque than some other attributed landscapes, shows his capacity for rendering natural scenes with a gentle, pastoral charm.

He also produced mezzotints, a printmaking technique that allows for soft gradations of tone, after his uncle's paintings. This was an important way of disseminating images of Thomas Gainsborough's work to a wider public and also provided Dupont with another avenue for his artistic skills. His mezzotints are valued for their fidelity to the spirit of the original paintings.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Gainsborough Dupont's oeuvre, illustrating his skill and artistic concerns.

"Charity Relieving Distress" is a notable subject picture, depicting a young woman and five children receiving alms in the backyard of a wealthy household. Such sentimental genre scenes, often with a moral or social message, were popular in the late 18th century, appealing to the era's "cult of sensibility." The painting reflects contemporary concerns about poverty and benevolence, and Dupont handles the composition and emotional tenor with considerable skill.

"The Blue Boy," one of Thomas Gainsborough's most iconic paintings, has an interesting, albeit debated, connection to Dupont. While traditionally identified as a portrait of Jonathan Buttall, the son of a wealthy hardware merchant, some modern scholarship has proposed that the sitter might actually have been the young Gainsborough Dupont himself. The painting, created around 1770, is a clear homage to Van Dyck, particularly in the boy's striking blue satin costume. If Dupont were indeed the model, it would add another layer to his early immersion in his uncle's artistic world and his engagement with the Van Dyckian tradition. Regardless of the sitter's identity, the painting was a powerful statement by Thomas Gainsborough, showcasing his virtuosity and his challenge to the academic preference for warmer colors in portraiture, famously defying a dictum by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The "Portrait of the Artist's Nephew," as mentioned, is a significant work. If a self-portrait, it shows Dupont presenting himself with a quiet confidence, clad in a silk blue coat that again evokes the Van Dyckian influence. The handling of the fabric and the sensitive portrayal of the face are characteristic of his refined style.

His portrait of "Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley" (c. 1780), now in the Yale Center for British Art, depicts a notable and somewhat notorious clergyman, journalist, and magistrate of the period. Such commissions demonstrate Dupont's ability to secure patronage from prominent figures.

Working with Thomas Gainsborough: Assistant and Successor

Dupont's role as his uncle's assistant was crucial. In an 18th-century studio, assistants were involved in various tasks, from grinding pigments and preparing canvases to painting drapery, backgrounds, and even producing copies or replicas of the master's successful compositions. Dupont's intimate involvement in Thomas Gainsborough's studio meant he was privy to every stage of the creative process. He would have observed his uncle's interactions with sitters, his methods of composing a picture, and his experimental techniques with long brushes and thinned paints.

This close collaboration inevitably led to the stylistic similarities that sometimes blur the lines of authorship. It is known that Dupont helped his uncle complete unfinished paintings, particularly towards the end of Thomas Gainsborough's life and after his death in 1788. When Thomas Gainsborough died of cancer on August 2, 1788, he left his studio and unfinished works in the care of his nephew. Dupont took on the responsibility of completing these canvases, a task that required not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of his uncle's artistic intentions.

After his uncle's death, Gainsborough Dupont continued to operate from Schomberg House for a time. He exhibited his own works at the Royal Academy from 1790 to 1795, striving to establish himself as an independent artist. He painted portraits of notable figures, including members of the royal family, such as his "Portrait of Queen Charlotte" and "Portrait of George III."

The London Art World: Contemporaries and Context

Gainsborough Dupont worked during a golden age of British painting. The London art scene was dominated by towering figures. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, was Thomas Gainsborough's chief rival. Reynolds championed the "Grand Manner," an idealized style inspired by classical and Renaissance masters, and his "Discourses on Art" were highly influential. While Gainsborough admired Old Masters like Rubens and Van Dyck, his approach was often more intuitive and naturalistic than Reynolds's academicism. Dupont would have been acutely aware of this artistic rivalry and the differing philosophies it represented.

Other prominent portraitists of the era included George Romney, whose elegant and often more overtly classical portraits were highly fashionable, and Allan Ramsay, a Scottish painter admired for his sensitive and refined portrayals, particularly of women. Johann Zoffany excelled in conversation pieces and theatrical portraits, capturing the social life and cultural figures of the time. The American-born artists Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley also made significant careers in London, West succeeding Reynolds as President of the Royal Academy.

In landscape painting, Richard Wilson was a pioneer, bringing a classical, Italianate sensibility to British scenery, influenced by Claude Lorrain. Paul Sandby was a leading watercolorist, known for his topographical views. Thomas Gainsborough's own landscapes, with their poetic and often rustic charm, stood somewhat apart, influencing later artists like John Constable. Dupont's Poussinesque landscapes show him engaging with a different, more formal landscape tradition.

The Royal Academy exhibitions were major social and cultural events, where artists vied for critical attention and patronage. Dupont's participation in these exhibitions was essential for his visibility as an independent artist. He also faced the challenge of emerging from his uncle's shadow in a competitive market. The art world also included important female artists like Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, both founding members of the Royal Academy, who achieved considerable success, particularly Kauffman with her neoclassical history paintings and portraits.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Despite his talents and his connection to one of Britain's greatest painters, Gainsborough Dupont's independent career was tragically short. He died relatively young, on January 20, 1797, in London, at the age of 42, less than a decade after his uncle. He was buried alongside Thomas Gainsborough in the churchyard of St. Anne's Church, Kew.

His early death undoubtedly limited his potential to fully develop his own artistic voice and to build a more extensive body of work. For many years, his reputation was largely subsumed under that of his uncle. However, art historical scholarship has increasingly sought to distinguish his hand and to appreciate his contributions more fully. Exhibitions and publications focusing on Thomas Gainsborough and his circle have provided opportunities to re-evaluate Dupont's work.

The very fact that his paintings could be confused with those of Thomas Gainsborough speaks to the high quality of his technique and his deep absorption of his master's style. While he may not have possessed the innovative genius of his uncle, he was a highly accomplished painter in his own right, capable of producing portraits of considerable charm, sensitivity, and technical finesse. His landscapes, though fewer in number, demonstrate his versatility and his engagement with different artistic traditions.

His role in completing his uncle's unfinished works and in managing his studio after his death was also significant in preserving Thomas Gainsborough's legacy. The works that passed through his hands ensured that more of his uncle's vision was brought to fruition than might otherwise have been possible.

Collections and Market Presence

Works by Gainsborough Dupont are held in various public collections. The Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, has a notable collection, including the aforementioned portrait of Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley. The Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery in San Marino, California, also holds works by him. In the United Kingdom, Gainsborough's House in Sudbury, the museum dedicated to his uncle's life and work, naturally includes examples of Dupont's art. The National Portrait Gallery in London also has works attributed to him.

His paintings appear on the art market from time to time. For instance, in June 1973, Sotheby's in London auctioned eight of his works. More recently, in April 2024, an oil painting described as a portrait of Thomas Gainsborough's nephew (potentially "The Artist's Nephew") reportedly sold for £30,000. Such sales indicate a continuing, if modest, market interest in his work.

Conclusion: An Artist in His Own Right

Gainsborough Dupont remains a figure of interest not only for his familial and professional connection to Thomas Gainsborough but also for his own artistic merits. As his uncle's sole apprentice, he received an unparalleled artistic education, mastering the techniques and absorbing the aesthetic that made Gainsborough one of Britain's most beloved painters. His portraits are characterized by their elegance, sensitivity, and technical skill, often closely emulating his uncle's style yet possessing their own quiet charm. His exploration of Poussinesque landscapes reveals a broader artistic curiosity.

While the towering reputation of Thomas Gainsborough inevitably cast a long shadow, Gainsborough Dupont was more than a mere copyist or assistant. He was a talented and dedicated artist who made a valuable contribution to British art in the late 18th century. His early death curtailed a promising career, but the works he left behind, and the increasing scholarly attention they receive, ensure that Gainsborough Dupont is recognized as a skilled painter who played a vital role in the artistic life of his time and in the continuation of his family's remarkable artistic legacy. His life reminds us of the complex interplay of influence, talent, and circumstance that shapes an artist's journey.