Henry Edridge stands as a significant figure in British art during the late Georgian period. Born in Paddington, London, in 1768, into a family of modest means, his trajectory from an artisan background to becoming an acclaimed painter and an Associate of the Royal Academy exemplifies the possibilities for talent in his era. Edridge carved a distinct niche for himself, excelling particularly in miniature painting and developing a highly popular style of small-scale watercolour portraiture, while also exploring landscape painting later in his career. His life, spanning from 1768 to 1821, coincided with a vibrant period in British art, placing him amidst contemporaries who were reshaping the landscape of portraiture and watercolour painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Henry Edridge's journey into the art world began at the age of fifteen. Born into the family of a tradesman, his innate artistic inclinations led him to an apprenticeship under William Pether. Pether was a respected artist known for his skills in mezzotint engraving and miniature painting. This training proved foundational for Edridge, equipping him with the meticulous precision required for miniature work and the tonal understanding inherent in mezzotint, skills that would inform his later delicate pencil and watercolour techniques.

Following his apprenticeship, Edridge further honed his talents by enrolling as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the epicentre of artistic training and discourse in Britain, exposing students to the highest standards of academic drawing and painting. His time at the Academy allowed him to study the works of established masters and interact with fellow aspiring artists, broadening his artistic horizons beyond the specific crafts learned under Pether.

Even in his early years, Edridge's talent did not go unnoticed. His skill, particularly in creating faithful and delicate likenesses, caught the attention of one of the most influential figures in British art history: Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy and the leading portrait painter of his day, reportedly admired Edridge's work greatly. It is documented that Reynolds not only purchased examples of Edridge's art but also commissioned him to make miniature copies of his own paintings, a significant endorsement for the young artist.

The Rise of a Portraitist

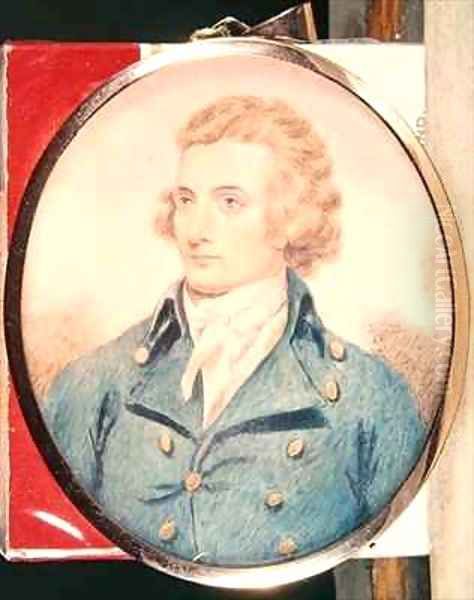

Edridge quickly established a reputation for his portraiture, particularly for his small-scale works. Initially, like many miniaturists of the period such as Richard Cosway and George Engleheart, he worked on ivory, a traditional support for miniatures that lent a luminous quality to the finished piece. However, Edridge soon transitioned to working primarily on paper. This shift allowed for a different approach and scale, moving slightly away from the intimate jewel-like quality of traditional miniatures towards something more akin to small drawings or cabinet pictures.

His characteristic technique became highly sought after. He typically began with a detailed drawing in graphite (black lead pencil), carefully delineating the features and form of the sitter. Over this precise underdrawing, he applied subtle washes, often in India ink or neutral tints, to build up tone and volume, creating a sense of three-dimensionality reminiscent of mezzotint tonality. Finally, he would add delicate touches of watercolour to suggest local colour – the complexion, hair, and clothing – often maintaining a restrained palette that allowed the underlying drawing to remain prominent.

This distinctive style offered a compelling blend: the accuracy and detail associated with miniature painting combined with the relative freedom and atmospheric potential of watercolour. His portraits were often full-length or three-quarter length figures, set against lightly indicated backgrounds, sometimes featuring architectural elements or landscape vignettes. This format proved immensely popular with patrons seeking likenesses that were elegant and refined, yet less formal and costly than large-scale oil portraits by artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, a near-contemporary who dominated grand portraiture.

Notable Subjects and Patrons

Edridge's success attracted a distinguished clientele drawn from the aristocracy, political circles, the clergy, and the cultural elite of Georgian Britain. His ability to capture a good likeness in a refined and fashionable style made him a popular choice for those wishing to commemorate themselves or their families. His list of sitters reads like a 'who's who' of the era.

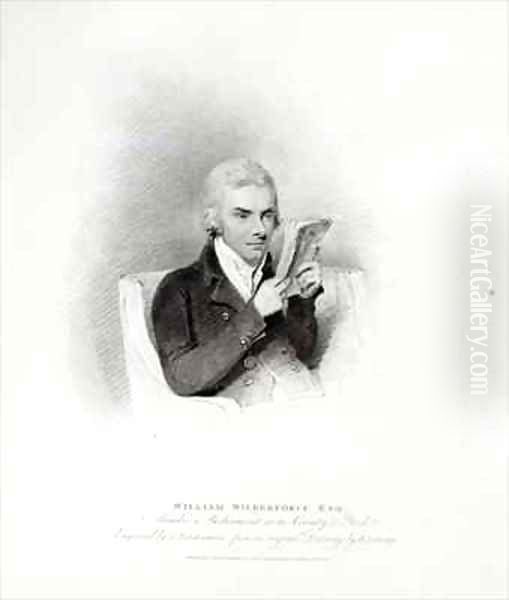

He famously depicted key figures such as the naval hero Admiral Lord Nelson, the explorer Mungo Park, and the influential Methodist leader Reverend Thomas Coke. Political figures also sat for him, including Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. Literary and intellectual figures were captured by his pencil and brush, such as the poet Robert Southey and the abolitionist William Wilberforce. He also portrayed prominent members of society and industry, like the piano manufacturer Thomas Broadwood, depicted with his son John Broadwood and a sporting gun.

The portrait of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, is another significant work attributed to Edridge, likely based on earlier likenesses but rendered in his characteristic style, ensuring its wide dissemination through copies and engravings. His miniature of Sir Joshua Reynolds, likely one of the copies commissioned by Reynolds himself, further cemented his connection to the artistic establishment. The sheer range of his sitters underscores his prominence and the broad appeal of his portrait style during his lifetime.

Miniatures and Small Portraits: A Speciality

While Edridge worked in various formats, his small-scale portraits on paper remain his most defining contribution. These works occupy a unique space between traditional miniature painting and larger portrait drawings. They retained the fine detail and careful finish expected of miniatures but were executed with the graphic sensibility of drawing, enhanced by watercolour.

His technique allowed for a high degree of finish without sacrificing freshness. The graphite underdrawing provided structure and precision, particularly in rendering the face and hands, while the transparent washes of ink and watercolour added subtle modelling and colour accents. The backgrounds were often treated more loosely, providing context without distracting from the sitter. This approach was particularly effective for full-length portraits on a small scale, allowing him to depict the sitter's posture, fashion, and setting with elegance and economy.

Compared to the often flamboyant style of Richard Cosway or the solid, enamel-like finish of John Smart, Edridge offered a more delicate, graphic alternative. His contemporaries in miniature painting also included Andrew Plimer and his brother Nathaniel Plimer, as well as Ozias Humphry, each with their own stylistic nuances. Edridge's particular blend of pencil and watercolour, however, proved exceptionally popular and influential, bridging the gap between the intimate world of the locket-sized miniature and the more public display of larger portraits.

Expanding Horizons: Landscape Painting

While portraiture formed the bedrock of his career and reputation, Henry Edridge harboured a growing interest in landscape painting, particularly in watercolour. This interest intensified in the later part of his career. Seeking to develop his skills in this genre, he is said to have studied with Thomas Hearne, an established watercolourist known for his topographical views and antiquarian subjects. Hearne's precise drawing style likely resonated with Edridge's own meticulous approach.

Edridge's engagement with landscape also connected him to one of the most innovative circles in British watercolour history. He was associated with Dr. Thomas Monro, a physician and passionate art collector whose house served as an informal 'academy' for young artists. Here, aspiring painters like J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin gathered in the evenings to copy works from Monro's collection, often works by artists like John Robert Cozens. Edridge is known to have frequented this circle and even travelled and sketched with Thomas Girtin between 1795 and 1797. Girtin was a revolutionary figure in watercolour, pushing the medium towards greater atmospheric expression and breadth. Edridge is known to have copied Girtin's work, absorbing influences from his younger, more radical contemporary.

To further his landscape studies, Edridge undertook trips abroad. In 1817 and again in 1819, he visited France, travelling through Normandy. These excursions provided him with fresh subjects – picturesque towns, coastal scenes, and architectural studies – which he recorded in numerous watercolours. These landscapes often display a similar delicacy to his portraits, characterized by careful drawing, subtle washes, and an emphasis on light and atmosphere, though perhaps less groundbreaking than the work of Turner or Girtin, or the later landscapes of John Constable.

Representative Works and Style

Edridge's oeuvre includes numerous portraits and landscapes, many held in major collections today. Among his most representative works, the portraits of Lord Nelson, William Pitt, Robert Southey, and the Broadwoods exemplify his skill in capturing likeness and character within his distinctive small-scale format. His miniature of Sir Joshua Reynolds remains a testament to his early skill and prestigious connections.

In landscape, his Eton from Windsor Castle (1806), now in the Yale Center for British Art, is a fine example of his topographical work, showcasing his careful rendering of architecture and scenery, bathed in a soft light typical of his watercolour style. His French and Norman views further demonstrate his capabilities in landscape, often focusing on picturesque detail and atmospheric effects.

Stylistically, Edridge's work is characterized by its refinement, precision, and elegance. His pencil work is consistently fine and descriptive. His use of watercolour is typically restrained, favouring delicate washes and subtle tonal gradations over bold colouristic effects seen in some contemporaries like Paul Sandby or later watercolourists. His compositions are generally well-balanced and clear. While perhaps not as innovative as Turner or Constable, his style perfectly suited the tastes of his patrons, offering a sophisticated and detailed representation of both people and places.

Artistic Circle and Contemporaries

Henry Edridge operated within a rich network of artists, patrons, and institutions. His training under William Pether and his time at the Royal Academy Schools placed him firmly within the established structures of the London art world. His early recognition by Sir Joshua Reynolds provided a crucial boost to his career.

His association with Dr. Thomas Monro connected him directly to the burgeoning English watercolour school, bringing him into contact with the prodigious talents of Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner. While Girtin's influence seems more direct, particularly on Edridge's landscape work, the shared environment fostered artistic exchange. His later study with Thomas Hearne further demonstrates his engagement with established landscape traditions, alongside figures like Paul Sandby and Francis Towne.

As a successful portraitist, he inevitably worked in the same market as Sir Thomas Lawrence, although generally serving a slightly different niche with his smaller-scale works. In the field of miniature painting, he was a contemporary of leading figures like Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, John Smart, Ozias Humphry, and the Plimer brothers (Andrew and Nathaniel). His work offers a distinct alternative to theirs, emphasizing graphic qualities alongside delicate colouring. His career also overlapped with the rise of major landscape painters like John Constable, though their artistic paths diverged significantly. The collector Edward Landseer (father of the famous animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, or perhaps Sir Edwin himself later) owning his work indicates the continued appreciation of his art.

Technique and Style Revisited

Edridge's technical approach was central to his success. The combination of graphite pencil and watercolour on paper became his signature style, particularly for portraits. The meticulous pencil underdrawing provided the accuracy and detail his clients desired, capturing not just the likeness but also the textures of fabrics and details of costume. The application of grey or neutral washes (often India ink) built form subtly, creating soft shadows and a sense of volume without heavy impasto or opaque colour.

The final touches of watercolour were applied judiciously, often restricted to flesh tones, hair colour, and key elements of clothing or background. This technique retained a sense of lightness and transparency, distinguishing his work from oil paintings or heavily worked gouache miniatures. It allowed for relatively quick execution compared to oils, while still achieving a high degree of finish and refinement.

In his landscapes, a similar approach is often evident: careful drawing defines the scene, while transparent washes create atmosphere and light. His travels in France and Normandy seem to have encouraged a slightly broader handling in some later landscapes, perhaps reflecting the influence of Girtin or the changing tastes of the time towards more atmospheric effects, as pioneered by artists like John Robert Cozens.

Recognition and Legacy

Henry Edridge achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His popularity as a portraitist provided him with a steady income and a prominent position in London society. The ultimate institutional accolade came late in his career when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in November 1820, just months before his death in April 1821. This election confirmed his standing within the official art establishment.

His work was widely admired for its elegance, accuracy, and delicate finish. While subsequent generations might have favoured the bolder innovations of Turner or Constable, Edridge's art perfectly captured the refined sensibilities of the late Georgian and Regency periods. His particular style of small-scale watercolour portraiture was highly influential and widely imitated, serving a significant market demand.

Today, Henry Edridge's works are held in major public collections worldwide, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Royal Collection. He is remembered as a master of the small-scale portrait, an artist who skillfully blended the precision of the miniaturist tradition with the evolving techniques of watercolour painting. He remains an important figure for understanding the art market and tastes of his time, a bridge between the meticulous craft of the 18th century and the burgeoning expressive potential of watercolour in the early 19th century.

Conclusion

Henry Edridge's career traces a path from humble beginnings to significant artistic achievement. Through diligent training and the development of a distinctive and highly popular style, he became one of the leading portraitists of his day, particularly renowned for his elegant small-scale works in pencil and watercolour. His sitters comprised the elite of Georgian society, and his art captured the refined aesthetics of the era. While also exploring landscape, his primary legacy lies in portraiture, where he skillfully combined meticulous drawing with delicate watercolour washes. Elected an Associate of the Royal Academy shortly before his death, his work continues to be appreciated for its technical finesse, historical significance, and enduring charm, securing his place as a notable artist within the rich tapestry of British art history.